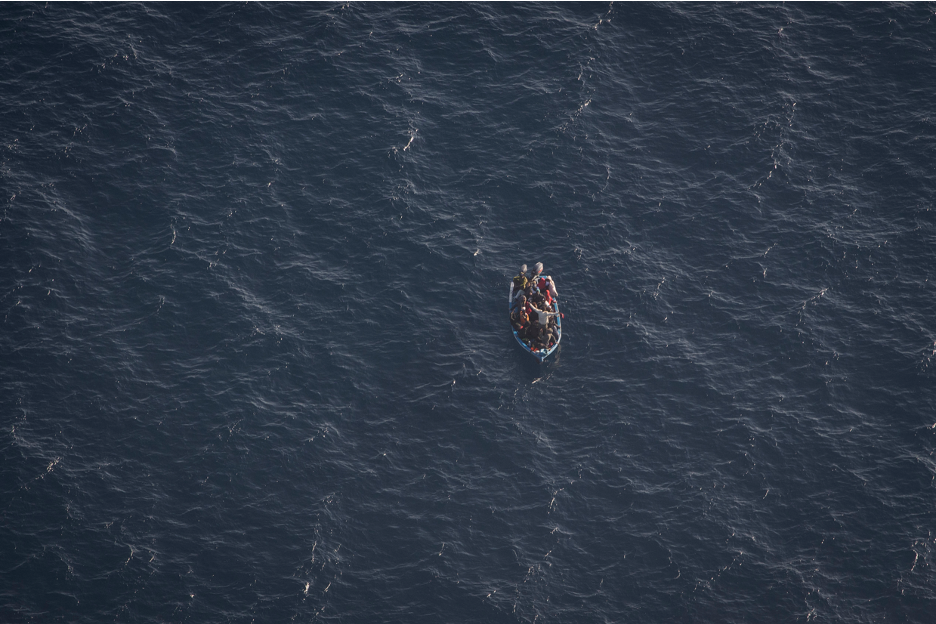

Boat in distress in the Maltese SAR Zone, 14 February 2020, Copyright: sea-watch.org

Introduction

Over the past six months, January to June 2020, the Central Mediterranean Sea has continued to be a zone of violence, human rights abuses, disappearances and deaths, as well as a stage of struggles for freedom of movement, both by people fleeing Libya and by the Civil Fleet. The ongoing conflicts in Libya and attempts to further close European harbours to migrants have exacerbated the already dire conditions of people who are trying to escape torture camps and to reach Europe. Most recently, using the excuse of having to ‘protect’ from the Covid-19 virus, European authorities have reinforced its repressive border control industry through EU air surveillance, by engaging merchant vessels or ghost fleets in illegal push-backs, and by providing money and resources to strengthen the illegal operations of the so-called Libyan coastguards. Despite European attempts to militarise external borders, to deter people’s movement and to facilitate the capture and detention of those crossing the sea, thousands of people have bravely managed to evade capture and to reach Europe, either autonomously or through the support of the Civil Fleet.

In 2020, so far, the Alarm Phone has supported 77 boats in distress in the Central Mediterranean Sea, carrying about 4,500 people. This does not include dozens of boats that called us but where we were unable to establish sufficient contact to retrieve crucial information, such as GPS positions. About 3,350 people who had reached out to us reached Europe, mostly due to the incessant efforts of the Civil Fleet: Sea Watch 3, Moonbird, Open Arms, Mare Jonio, Aita Mari and Ocean Viking. Besides rescues, people have reached European shores also independently, often coming from Tunisia.

Unfortunately, over 1,100 of the people who called us were intercepted by the so-called Libyan coastguards and by merchant or private vessels and forced back to Libya. We were also alerted by many hundreds of others in distress to whom contact broke down before we could gain crucial information. In these instances, we often could not find out what happened to them afterwards. We also learned of several shipwrecks and tragedies at sea where hundreds of people were confirmed dead or went missing. Although often presented as inevitable accidents, this loss of life could have been prevented, had it not been for efforts to deter people from reaching Europe, no matter the costs.

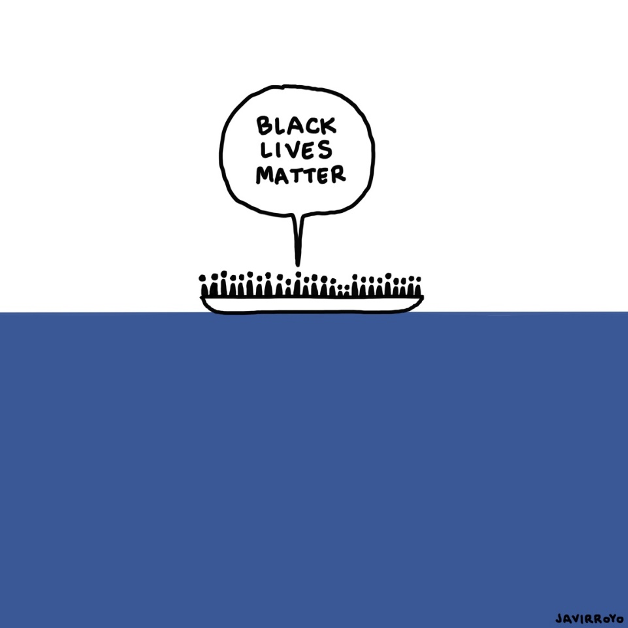

Over recent months, the EU has further improved its cynical ways of enforcing borders through modes of selective visibility and presence. While de facto withdrawing assets at sea in order to avoid rescue operations, EU aerial assets are regularly deployed to surveille migrant boats from the sky. In the contested Libyan Search and Rescue (SAR) zone, EU aerial assets have facilitated the interception and capture of thousands of migrants back to the Libyan warzone. Systematic violations of SAR obligations and human rights occur also within EU SAR zones, where European aerial assets have watched people drown and die of hunger and thirst from above, instead of organising their rescue. Thus while extensively monitoring the Mediterranean, Europe has tried to invisibilise the dramatic effects of its letting-die policies, actively turning the Mediterranean into a black hole where Black Lives on the move are systematically left to die, illegally pushed back, or kept at sea for days without assistance.

It is only thanks to survivors who have bravely chosen to speak up and testify, as well as to the counter-surveillance activities of the Civil Fleet, that we have gained glimpses into the crimes that EU institutions and member states perpetrate at Europe’s external borders. Their testimonies from detention, video footage survivors shared with us, and people’s attempts to reconstruct what happened to their missing loved ones, exposed otherwise unimaginable human rights violations perpetrated by the Armed Forces of Malta and by Libyan authorities with the support and complicity of Italian and European authorities. Once more, they have proven that Italy’s and Malta’s violent and deadly practices of non-assistance or delays, sabotage and attacks at sea, push-backs and capture of people fleeing war and torture, are by no means exceptional but strategic and systematic in the Central Mediterranean Sea.

As this analysis will show in detail, these practices escalated in particular over the Easter weekend, shortly after Malta and Italy had declared their harbours ‘closed’ for migrants in distress, grotesquely using the Covid-19 pandemic as an excuse to let people die at sea, needlessly suffer or be detained on floating prisons outside territorial waters. The absence of EU assets and NGO rescuers did not prevent people from trying to escape the Libyan warzone. Many of them were deliberately left adrift in the Maltese SAR zone for days or illegally pushed back to Libya by Malta’s ghost fleet. In what became known as the ‘Easter tragedy’, twelve people were killed by the European border regime.

This analysis is organised into five sections:

- A chronology of Alarm Phone experiences and important developments in the Central Mediterranean region over the past six months

- An account of Malta’s escalating border violence in the context of the Covid-19 pandemic, focusing on Maltese ‘ghost vessels’ and ‘offshore prisons’

- A brief assessment of the newly launched Eunavfor operation IRINI

- Case studies of rescues and push-backs by merchant vessels

- An analysis of the situation in Tunisia which is often overlooked in discussions around the Central Mediterranean border struggles.

1 Chronology

January 2020

2020 began how 2019 had ended: the war in Libya continued with heavy shelling and casualties, especially in Tripoli. Already in the first days of the new year, hundreds of people used good weather spells to try to escape. Overall, 27 boats reached out to the Alarm Phone in January, not including the many boats that called us but where contact was lost before we could receive crucial information, such as their GPS positions.

For the Alarm Phone, the four days between 9-12 January were particularly tough – we were alerted to boats with about 1,150 people on board. In total, about 1,500 people fled from Libya over these days, and 503 of them reached Europe. 237 people on five separate boats in distress were rescued by the amazing efforts of NGO crews and through the cooperation of the Civil Fleet: Sea Watch 3, Moonbird, Open Arms, and Alarm Phone. Over 900 people did not make it and were forcibly returned to Libya within the first two weeks of 2020. Among them was a group of 64 people who were returned by a commercial vessel. Upon arrival in Tripoli harbour, the group refused to disembark and was later forced off the boat. In this violent process, one person was executed by the Libyan authorities and his body was thrown into the sea.

Although other groups sought to escape in between, for example one that was rescued by Ocean Viking after calling the Alarm Phone on 17 January, the second larger spell of departures occurred between 24 and 27 January 2020 when over 930 people boarded 15 flimsy boats in Libya – about 850 of them reached Europe. The Alarm Phone was alerted to nine of these boats, carrying about 650 people on board. Fortunately, all of them succeeded in their struggle to escape war-torn Libya and reached Europe. Seven boats were rescued by the Civil Fleet, four by the Ocean Viking, two by the Open Arms, and one by the Alan Kurdi. Two of them were rescued by the Armed Forces of Malta in the Maltese SAR Zone, after the Maltese authorities delayed rescue procedures. Six other boats with 283 people on board did not reach out to us. Of those, one was rescued by Alan Kurdi, one by the Ocean Viking, one by Italy, one reached Italy autonomously, and two were intercepted by Europe’s allies, the so-called Libyan coastguards.

Between 29-30 January, Open Arms rescued further groups in distress through collaboration with Alarm Phone, increasing the total to 363 survivors on board who were denied disembarkation by Malta but later received permission to land in Pozzallo, Italy.[1] On 30 January, a group of 17 people called us from within the Maltese SAR zone but was then captured by Libyan forces and abducted back to Libya by the coastguard ship Fezzan. Sea-Watch’s aircraft Moonbird had witnessed this illegal pull-back operation. A day later, 47 reached out to us when in distress and were later rescued by the Maltese armed forces.

February 2020

Throughout February, we assisted 18 boats in distress, not including the many boats that called us but where contact was lost before we could receive crucial information, such as their location. Overall, 1,899 people reached Europe via the central Mediterranean route that month. We repeatedly documented cases of delay and non-assistance – in particular involving Maltese authorities.[2] In February, the period with the most cases occurred between 16-19 February during which we were alerted to 14 boats, carrying at least 1,095 people. Of these 14 boats, six with about 507 people on board were rescued to Europe, four of those by NGOs. Six boats with approximately 418 people on board were returned to war by the so-called Libyan Coastguards. The fate of 2 boats with about 160 people remained unconfirmed, though we presume that they were also intercepted back to Libya.[3]

On 9 February, we alerted European and Libyan authorities, as well as the public, to two boats in distress. One was spotted by the Moonbird and later rescued by the NGO Aita Mari. The other boat was in grave danger off Libya’s coast. There were 91 people on board who said that their boat was taking in water. The authorities we alerted did not react adequately – in fact the officer of the so-called Libyan coastguard said that they would not conduct an operation as their detention centres were overcrowded. We lost contact to the people in distress and never reconnected. In the aftermath, we contacted RCC Malta, MRCC Italy, authorities in Libya, and Frontex to find out more about this case, but never received a response. In contrast to this institutional silence, several relatives and friends of the missing started to reach out to us and passed on names and pictures of the missing. Based on their testimonies, and our investigations on this case, we now assume that a shipwreck has occurred and that none of the 91 people survived.

In late February, the Ocean Viking crew and 274 rescued guests on board had to go into quarantine, imposed by the Italian interior minister, citing Corona-virus concerns. Clearly, and according to MSF, the measure served “as a pretext to prevent the Ocean Viking from resuming its lifesaving work in the central Mediterranean.”[4] In March, similar measures would affect the ability of a range of other NGOs to conduct rescues at sea.

March 2020

In March, the Alarm Phone worked on merely two distress cases in the central Mediterranean Sea. The decline in cases that month reflected the overall decrease in crossings, with merely 241 people reaching Italy and 146 Malta. While this decrease has a variety of reasons, including the situation within Libya and the weather conditions, about 630 migrants did not reach Europe due to reinforced interception operations.[5] Over one weekend in mid-March alone, 406 people were captured at sea and forced back to Libya.[6]

One boat, carrying 49 people, reached out to Alarm Phone on 14 March from within the Maltese SAR zone, but was later intercepted by the Libyan coastguard and in cooperation with RCC Malta and the EU border agency Frontex. Instead of complying with refugee and human rights conventions, the Maltese authorities coordinated a grave violation of international law and of the principle of non-refoulement, as the rescued must be disembarked in a safe harbour.[7] On the same day, we alerted the Armed Forces of Malta to a second boat in distress in the Maltese SAR zone with about 110 people on board. Before their eventual rescue, the people spent about 48 hours at sea. Malta delayed the rescue for more than 18 hours, putting 110 lives at severe risk. Non-assistance, delays, and pushbacks are becoming the norm in the Central Mediterranean, causing trauma in survivors, disappearances and deaths, both at sea and in Libya.

63 people fleeing from Libya, before they were illegally pushed-back to Libya

April 2020

In April, the situation in the central Mediterranean further escalated. The Alarm Phone was alerted to 10 distress cases, not including the many boats that called us but where contact was lost before we could receive crucial information, such as their location. In total, 737 people succeeded to cross the central Mediterranean and reach Europe that month. Merely between 5-11 April 2020, over 1,000 people on more than 20 boats left the Libyan shore. European authorities used the Covid-19 health crisis to normalise the already existing practice of non-assistance at sea.[8] First Italy, then Malta, declared their harbours ‘unsafe’ for migrant landings. Ostensibly implemented in the name of ‘saving lives’, these measures had the opposite effect: people were left at serious risk of dying in distress at sea and at least a dozen deaths were the direct consequence.

Due to increasing restrictions imposed by European countries, many NGOs were prevented from returning to the death-zone off Libya. Only the Alan Kurdi of Sea-Eye was present in early April and immediately carrying out rescue operations. On 6 April, the Alan Kurdi rescued 68 people while being attacked by Libyan forces, which cause many of the distressed to jump into the water.[9] On the same day, another 82 people were rescued off a wooden boat after the supply vessel Asso Ventinove had denied them rescue for hours.[10] While the Alan Kurdi and Alarm Phone were struggling to rescue those fleeing from Libya to Europe, European authorities were busy organising mass interception campaigns. In April, about 400 people were returned to the Libyan warzone.[11]

Especially Malta escalated its deterrence efforts, sabotaging boats, delaying rescue, orchestrating private push-back operations, thereby causing multiple deaths. On 9 April, the Maltese Armed Forces attacked a boat in distress with 66 people on board after leaving them in distress for about 40 hours. After sabotaging it, a Maltese officer told the migrants: “I leave you to die in the water. Nobody will come to Malta.”[12]

Over the Easter weekend, 10-13 April, the Armed Forces of Malta consciously left one boat with 47 people adrift – they only survived due to the intervention by the NGO Aita Mari on 13 April.[13] Malta failed also to rescue a second boat with 77 people in the Malta SAR zone, that later reached Sicily. A third boat, with 63 people on board, was left to drift for days in the Maltese SAR zone while both the AFM and Frontex were monitoring from the sky how several people died on board. In total, 12 people lost their lives due to Malta’s failure to assist and survivors were illegally forced back to Libya through a covert push-back operation orchestrated by Malta.[14] A fourth boat with 101 people on board reached Pozzallo – weeks later we were able to uncover how the people had been left in distress and threatened by the AFM before being equipped with petrol and an engine so that they could move on to Italy.[15]

Aita Mari, credits Pablo Garcia/AFP

May 2020

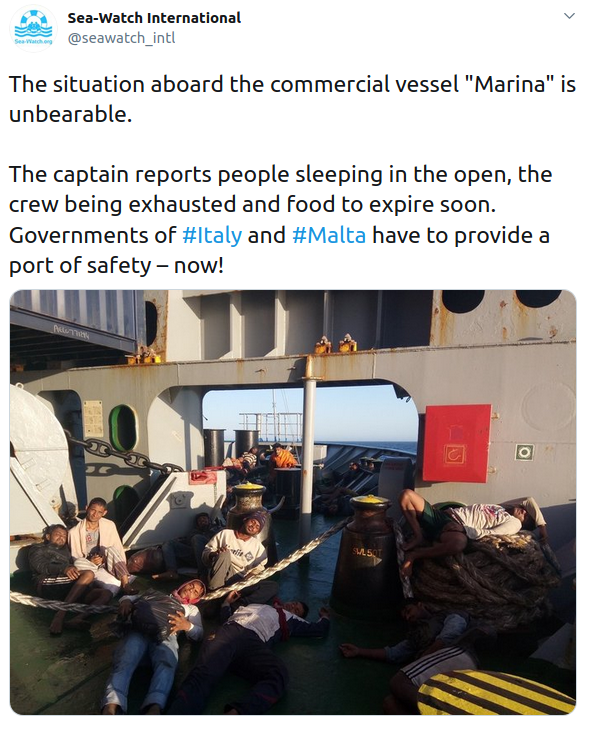

In May, 1,708 people escaped via the central Mediterranean route and reached Europe. Alarm Phone assisted 13 boats in distress, not including the many boats that called us but where contact was lost before we could receive crucial information, such as their location. Hundreds of people reached Italy independently, seemingly well aware of the systematic push-back and non-assistance strategies carried out by Malta in the weeks prior.[16] Over the course of the month, 774 people were intercepted at sea and forcibly returned to Libya.[17] Among them were 98 people who had reached out to the Alarm Phone but were illegally pushed back by the Portuguese flagged commercial vessel AS Anne after rescue in late May.[18] Other commercial actors have decided against returning migrants to a warzone. When the commercial vessel Marina rescued 78 people who had called the Alarm Phone, they brought them to a port of safety in Italy, where they were allowed to disembark after a five-day long stand-off near Sicily.[19]

Also in May, Malta continued to systematically violate human rights, frequently delaying and denying rescue, and sought to find new agreements with Libyan authorities.[20] Though forced through public pressure to engage in several rescue operations, the Maltese authorities began to imprison the rescued off its shores in floating detention centres.

Over the course of several weeks, a total of 425 rescued people were imprisoned in private ferry vessels, as Malta refused to allow them to land.[21] Several of them had reached out to the Alarm Phone when they had been in distress at sea. Now on one of the Captain Morgan ferries, one of the rescued reached out to the Alarm Phone, reporting of the inhumane condition in the “water prison” and the “deplorable state” they were in. According to him, some of the imprisoned had attempted to take their lives and others had launched a hunger strike.[22]

While EU institutions remained silent on the mass deprivation of rights and freedoms, civil society groups in Malta and beyond pressurised the government to end its cynical offshore detention.[23] In the end, it was due to migrant protests on board that their imprisonment was ended. With some having to endure off Malta’s coast for about five weeks, their ordeal was ended on 6 June.[24]

Also in May, several lives were needlessly lost. One person who was kept in quarantine onboard the commercial vessel Moby Zaza off Sicily jumped overboard and drowned on 20 May.[25] Three days later, two shipwrecks occurred off the coast of Tunisia, with at least seven fatalities feared.[26] In Libya, 30 migrants, including 26 Bangladeshis, were slaughtered in late May in the town of Mizda by the family of a Libyan trafficker.[27]

June 2020

In June, the Alarm Phone assisted people on 7 boats in distress, not including the many boats that called us but where contact was lost before we could receive crucial information, such as their location. Over the month, three shipwrecks were officially documented in the central Mediterranean Sea. On 6 June, at least 54 people, predominantly from sub-Sahara Africa, died when a boat coming from Tunisia capsized near the city of Sfax.[28] On 13 June, Alarm Phone was contacted by a relative who reported on a shipwreck that occurred near Zawiya in Libya with at least 12 people losing their lives.[29] On 20 June, World Refugee Day, another shipwreck occurred off the coast of Libya. 19 people were rescued by a fisherman and the death toll is still unclear.[30]

In order to counter this ongoing mass dying, the several NGOs returned to the central Mediterranean in June, successfully resisting European attempts to prevent their missions. First Sea-Watch, then Mediterranea and SOS Mediterranee returned to the sea and Moonbird continued its aerial counter-surveillance operations.[31] On June 9, Moonbird spotted three escaping boats and alerted Sea-Watch but supported by the European authorities, the so-called Libyan coastguard was quicker and abducted the approximately 250 people on board back to a warzone where in June several mass graves were detected, including a baby that was born on a boat in distress.[32] Overall, about 1,069 people were intercepted by Libyan forces that month.

Fortunately, three boats were detected and rescued by Sea-Watch between 17 and 19 June, carrying a total of 211 people.[33] Mediterranea’s Mare Jonio rescued another 67 people on 19 June.[34] Both rescue ships then disembarked the rescued in Sicily where they were placed in quarantine.

2 Malta’s escalating border violence

On 8 April, the Italian government released a decree declaring that Italy was not a place of safety for migrants rescued outside the Italian SAR zone anymore, due to the Covid-19 pandemic. The following day, the Maltese government responded with a similar declaration, announcing that Malta would stop any SAR operations due to a lack of resources in the Armed Forces of Malta. Both Italy and Malta used the pandemic as an excuse to declare their harbours ‘unsafe’, a perfidious strategy to prevent migrants from entering the EU. The consequences of this strategy were severe for people fleeing from Libya: the already-existing rescue gap in the central Mediterranean was enlarged, and delays and instances of non-assistance increased.

The five didn’t survive Malta’s non-assistance at sea on Easter. Seven more lives were lost during that days

Malta’s “Ghost Fleet”

The Maltese government has hired several private “fishing” vessels, including the Dar al Salam 1 and the Tremar, flying the Libyan flag, not only for the illegal pushback of 63 people to Libya during the Easter weekend. By deploying these private vessels, Malta seeks to conceal its role in human rights violations, seemingly allowing the government to deny responsibility. Malta’s prime minister Robert Abela and his government have refused to admit their implication in serious human rights violations while those who were used to broker the push-back, including Neville Gafà, have stated that their services had been sought after by the government.

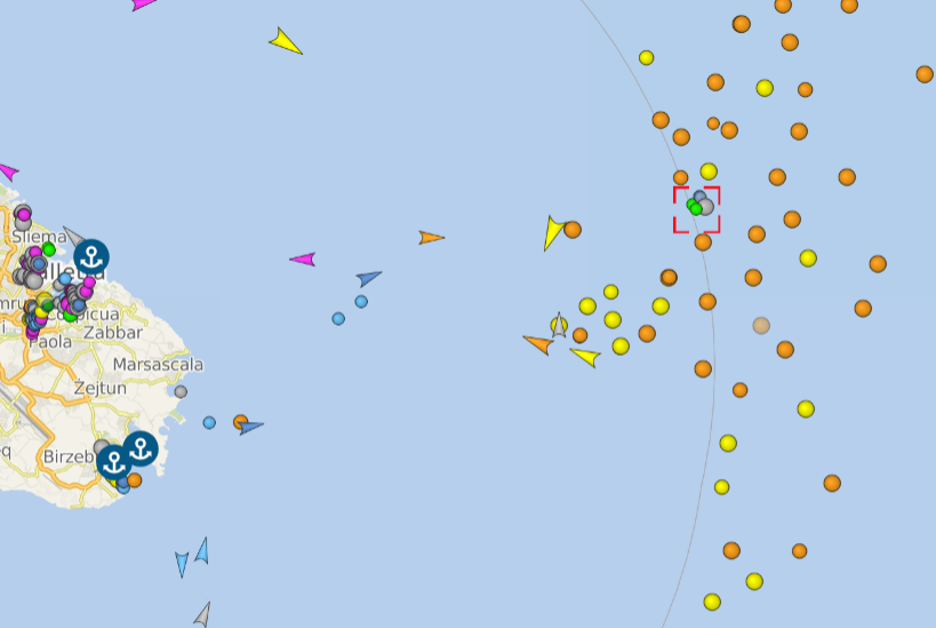

Besides their involvement in the ‘Easter massacre’, these private vessels have engaged in several other activities in the central Mediterranean. Switching off their AIS transponder, these vessels operate often hidden from public attention. On 28 April, the Armed Forces of Malta ordered the Dar al Salam 1 to intercept/capture 62 people in distress, who had reached out to Alarm Phone, within the Maltese SAR zone. After we raised public attention to the danger of another illegal push-back to Libya, the people were eventually brought to the Captain Morgan vessel Europe II and kept in offshore detention.

On the 7 May, the Dar al Salam 1 was ordered again to conduct an operation, taking on board 78 people. Also in this case they were detained off Malta’s shore on a Captain Morgan vessel. In mid-May, the Tremar was ordered by RCC Malta to take about 50 people onboard: they had been rescued south of Lampedusa. Malta had requested Lampedusa as port of disembarkation, but eventually also this group was brought to a Captain Morgan vessel outside Maltese territorial waters on 23 May.

Malta’s acts of delay, non-assistance, and sabotage, as well as its role in organising illegal and privatised push-backs that prompted at least twelve fatalities, were not left unopposed. The Maltese NGO Repubblika filed a criminal complaint against Malta’s prime minister over the deaths at sea, and against twelve members of the AFM for sabotaging a migrant boat. The magistral inquiry soon concluded that there was no evidence of wrongdoings by either prime minister or AFM, suggesting that Malta had fulfilled its obligation to adhere to SAR conventions. From the very beginning, this enquiry was seriously flawed, and the conclusions highlight a dramatic lack of factual evidence, significant legal mistakes, and mis-leading reconstructions of events. To any neutral observer it will be obvious that the magistrate’s enquiry was following a particular political agenda, desperate to downplay the criminal actions taken by Maltese authorities and to close the ‘investigation’ as quickly as possible. Nonetheless, survivors and relatives have not given up and have protested the conclusion of the enquiry, demanding further investigation.

Picture of the Dar al Salam 1

Captain Morgan vessels outside of Malta territorial water. Source: Vesselfinder

Quarantine Vessels and Floating Prisons

One consequence of the supposed closure of Italian harbours was the isolation of people rescued by NGO vessels Alan Kurdi and Aita Mari around Easter in the vessel Raffaele Rubattino. In mid-May, Italy installed also the ferry boat Moby Zazà as a quarantine vessel where those arriving were kept isolated in quarantine. Only after two weeks, the rescued were allowed to touch European soil when they were brought to Sicily. On 19 May, a 28-year-old man jumped from the ship’s deck into the water to escape and drowned.

From 30 April on, Malta went even further, keeping 425 survivors of maritime distress situations on four tourist cruising vessels located outside of Maltese territorial waters. After EU member states had long before proposed the installation of detention centres off their shores, the Covid-19 pandemic was the occasion to let this old idea of floating hotspots become a reality. In Malta, the creation of floating prisons was not merely justified as constituting a quarantine measure but through the argument that Malta would lack space and capacity in (detention) camps. In doing so, the people were not given access to Maltese territory and jurisdiction, thus kept in international waters and prevented from applying for asylum in Europe. In fact, Malta used them as hostages to pressurise other EU-member states to relocate people.

The detained went on hunger strike and later on protested desperately against the inhumane detention conditions on board, eventually forcing the Maltese government to disembark them in Malta on 6 June. In public, the protestors were blamed for the uprising, the violent conditions that also prevented them from the right to claim asylum were largely ignored. This reversal of facts and the mis-portrayal of the rescued is not a novel strategy – demonstrated also in the infamous Elhiblu1 case.

On 28 May, Malta’s prime minister signed a new deal with Fayez al-Sarraj, the prime minister of the Libyan Government of National Accord, to prevent people from reaching Malta. From 1 July, they cooperate even more closely with one another, through two ‘interception coordination centers’, financed by Malta. The Maltese government accommodate three Libyan officers in the centre to support and coordinate border control and the capture of migrant boats back to the Libyan warzone, in violation of international law and human rights conventions, in Libya three Maltese officers are installed to arrange push-backs.

Survivors were kept on board a cruise ship for days outside of Maltese territorial waters

3 Operation IRINI

The EunavforMed military operation Sophia ended on 31 March 2020, and was replaced the following day by operation Irini (ironically, Greek for ‘Peace’), meant to be carried out until 31 March 2021. The operation claims to enforce the UN arms embargo to Libya with aerial, maritime and satellite assets. In addition, it supports the training of the so-called Libyan Coastguard and Navy to fight “human smuggling and trafficking networks”. Following the demands of the EU member states of Italy, Hungary and Austria, the operation does not involve any SAR activities in order to prevent migrant arrivals to Malta and Italy. According to the new procedure, in the event of a rescue, the rescued should be brought to Greece instead. The operational area of Irini ships is only in the eastern part of Libya’s coast, where migrant boats rarely depart. The operational plan is classified as confidential.

First experiences show that vessels of operation Irini indeed refuse to launch rescue operations, which is violates maritime law. On 12 June, a rescue was refused by an Irini military asset. On 26 June, Alarm Phone was alerted by a boat in distress 56nm east of Mistrata, in the heart of Irini’s operational area: yet, no EU military vessel was available for rescue. Instead, the people in distress were intercepted by the so-called Libyan Coastguard and deported back to Libya. The Mare Jonio rescue ship arrived on scene at the time of interception and offered to transship the people, but the so-called Libyan Coastguard refused.

4 Rescues and captures by merchant vessels

Since mid-March 2020, most of the NGO vessels were blocked due to the Covid-19 pandemic, and European coastguards often refused or delayed rescue operations, but merchant vessels were still utilised to carry out SAR operations. In May 2020, two boats that called Alarm Phone were rescued by merchant vessels. In one case, the 78 migrants on board the Marina could disembark in Italy after a long wait at sea while in the second case, the German vessel Anne returned 91 people to Libya – a violation of international law.

The case of Marina

In the night to 3 May, Alarm Phone received a distress call from a boat with 78 people fleeing Libya who, at the time of the call, were close to Lampedusa, but still in the Maltese SAR zone. On the phone they told us that they could see a big ship nearby. Relevant authorities failed to react to our calls. Our shift-team reached out to the German ship owner of Marina, Thies Klingenberg. Later in the day, he informed us that RCC Malta had given the order to the vessel to pick up the migrants, but he was waiting for instructions as to where to bring them. In the afternoon, RCC Malta told us that they had still no information regarding a safe port for the vessel: “It is a higher authority issue”, they said. On 4 and 5 of May there was no decision on where the Marina should bring the rescued migrants. The vessel was moving in circles in the Maltese SAR zone, south of Lampedusa. The ship owner informed the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Germany, the flag state of the ship, Antigua & Barbuda, as well as his lawyer in Malta. Finally, after five days of standoff, on 8 May, the merchant vessel was allowed to disembark the 78 migrants in Sicily and could leave Porto Empedocle for Malta, her original destination.

The case of MS Anne

In the morning of 25 May, Alarm Phone was called from a black rubber boat with more than 90 people on board, in the Libyan SAR zone. The situation on the boat was very tense, the people were crying, fearing to die, because water was coming in the boat and the engine stopped working. Our shift alerted the coastguards of Libya, Italy and Malta – without reactions. We lost contact to the boat and feared the worst. We found out that 3 merchant vessels were near the boat, among them the German cargo ship Anne, flying the Portuguese flag. We informed the authorities about it and called the shipping company of Anne, Reederei Jens & Waller GmbH&Co KG. They told us that they had already been ordered by MRCC Malta to move to the coordinates that we had received from the boat. Later, they confirmed that they were in charge of rescuing the boat and had received the order from MRCC Malta to take the people back to Libya. “We have to follow the instructions and see that we get the people off the ship as quickly as possible”, they said. As an answer to our argument that Libya is not a safe port, they said “go into battle with Malta” and hung up.

For a Portuguese flagged ship, it is illegal to bring people to Libya. We infomed ARCC Lisboa, and gave them all data about the boat and the vessel Anne. On May 27 at around 10 pm the people were disembarked in Misrata and returned to a torture camp. Some journalists and an NGO in Portugal reacted to our scandalisation. Pedro Pedrosa of the non-governmental organisation Humans Before Borders (HuBB) told the press: “In our opinion, the ship committed an offence under Portuguese private law, which was to put people in danger, […] and, on the part of the Portuguese state, possibly a violation of the Sea Convention and the Maritime Rescue Convention,” according to which “the state [flag] has to ensure that the master of the ship puts people in safe harbor,” and added that the organisation will “study all relevant legal mechanisms.”

Foreign Minister Augusto Santos Silva said that “Portugal has made representations to the European Commission, Germany and Malta to try to find an alternative landing, according to the legal rules and best European practices”. “The disembarkation of people at the port of destination, in Libya […], eventually took place before the diplomatic steps described above had had any useful effect”. According to the Minister, the ship was instructed by the Malta rescue centre to hand migrants over to the Libyan coastguard, but on 26 May, not having been boarded by the Libyan coastguard, the ship was instructed by the same rescue centre to proceed to the Libyan port of Misrata.

5 Tunisia: From Choucha Camp to disembarkation platforms

In 2011 and in the wake of the Libyan war, thousands of people fled to the Tunisian borders. Several camps were set up in the south-east of Tunisia. A few months later, all the camps were uninstalled with the exception of Choucha camp, which was officially dismantled in June 2017. The refugees and asylum seekers in the latter camp suffered from rudimentary hygiene and living conditions, and were exposed to a desertic climate, extremely cold nights and frequent sandstorms.

Following the intensification of the security crisis in Libya, the Tunisian government in collaboration with IOM and UNHCR as well as other UN organizations has anticipated the creation of a camp with a capacity to accommodate between 25,000 to 50,000 people in Bir El Fatnassia, located 25km from the town of Remada and 50km from the town of Tataouine near a military zone. The camp will be installed in the middle of the desert, in extreme climatic conditions, with no access to electricity or drinking water. Although Tunisia has repeatedly announced its refusal to install disembarkation platforms on its coasts, the EU continues to push and lobby for a further externalization of its borders in return for several economic advantages, investments, loans and visa facilitation procedures for the Tunisian elite.

So far, the role of the EU in this camp is not yet clear, however, there are several indications that this camp could be used as a disembarkation platform. Several questions remain open regarding this camp. We have noticed lack of transparency concerning the funding resources but also regarding the procedures in the settlement of migrants and refugees. Let us recall the absence of a legal framework for asylum in Tunisia, and Tunisia’s failure to provide adequate services for persons in need of protection, as evidenced by the Choucha camp. Will Tunisia actually be prepared to manage a contingency plan capable of accommodating up to 50 000 people or is it merely succumbing to the repeated pressure from the EU to externalize even more its borders and turn Tunisia into a tool for sorting out the “desirable and undesirable” migrants?

Ibn Khaldoun Shelter in Medenine (UNHCR Shelter)

The daily struggles of people on the move in Tunisia

According to the UNHCR, 4,434 persons are registered in Tunisia as refugees and asylum seekers up to May 2020. The vast majority are living in Greater-Tunis, Medenine and Sfax. Alarm Phone members have met some of them beginning of 2020. The interviewees reported that the conditions at the UNHCR centre in Medenine were deplorable and hygienic. There are an insufficient number of showers and toilets, shared by all the people in the centre and frequent water scarcity. Blankets and warm clothing for the winter are not distributed on time or in sufficient quantities.

The interviewees stressed the inadequacy of the 30 Tunisian dinars, per person per week, allocated for food through a voucher, which must also cover the purchase of clean drinking water that is not available at the centre. The apartments which are rent by the CTR in Sfax are usually unfurnished, and far away from the city. Regarding the situation in Greater-Tunis, at least 130 refugees and asylum seekers have been reported as homeless in December 2019.

As for access to health care, the CTR has set up an infirmary to care for refugees and asylum seekers. However, according to several testimonies, many people are refused care or asked for a bribe and most of the people find themselves obliged to pay private doctors with the food stamps that they were given.

Refugee status determination procedures generally last several months and in some cases even a year or more. According to several testimonies, refugees and asylum seekers are subject to continuous intimidation by humanitarian actors, mainly UNHCR and the CTR. Testimonies of violence, aggression and threats have been reported. Some have had their refugee cards confiscated or have been deprived of food stamps for weeks, simply because they have participated in peaceful protests to call for the acceleration of the refugee status determination procedure and the resettlement process.

Cases of psychological distress, depression, and self-harm are frequent in Ibn Khaldoun center in Medenine with, at least three people have attempted to commit suicide during the last months. After the mental and physical torture that people on the move have endured in Libya, they find themselves in Tunisia, a country that the EU would like to consider a safe country at all costs. After spending a few months there, the majority are forced to return to Libya, after being deprived of all rights and being subjected to psychological violence by UN organisations. Since 2011, these organizations have been constantly proving their incompetence to guarantee a dignified life for refugees, asylum seekers and migrants. The fate of these people remains uncertain, several have tried to reach Europe through Libya and with the new contingency plan, we fear a new Choucha Scenario.

____

[1] https://mobile.twitter.com/alarm_phone/status/1222474774338834432

https://twitter.com/openarms_fund/status/1223302497663684610?s=20

https://www.welt.de/politik/fluechtlinge/article205528969/Open-Arms-Italien-laesst-Rettungsschiff-mit-363-Migranten-anlegen.html

[2] https://mobile.twitter.com/alarm_phone/status/1227181371778650113

https://twitter.com/alarm_phone/status/1227641731119796226?s=09

https://twitter.com/alarm_phone/status/1227885052551475200

https://timesofmalta.com/articles/view/malta-monitoring-boat-with-60-people.770549

https://twitter.com/alarm_phone/status/1228277973133987841

https://twitter.com/alarm_phone/status/1232429204844707840

https://twitter.com/seawatch_intl/status/1231972023011880962

https://twitter.com/alarm_phone/status/1233128428074930176

https://twitter.com/alarm_phone/status/1233464381318582272

https://mobile.twitter.com/alarm_phone/status/1231881385096470530

[3] https://twitter.com/alarm_phone/status/1230210268296306694?s=09

[4] https://www.infomigrants.net/en/post/22974/ocean-viking-migrants-placed-in-quarantine-in-sicily

[5] https://twitter.com/alarm_phone/status/1246754853696745473 https://amp.theguardian.com/global-development/2020/apr/04/migrants-never-disappeared-the-lone-rescue-ship-braving-a-pandemic-coronavirus?__twitter_impression=true

[6] https://www.infomigrants.net/en/post/23448/over-400-migrants-returned-to-libya-over-weekend

[7] https://twitter.com/alarm_phone/status/1239125319765897217?s=20

https://twitter.com/alarm_phone/status/1239125317610070016?s=20

https://timesofmalta.com/articles/view/49-asylum-seekers-in-maltese-waters-taken-back-to-libya-and-beaten-ngo.778889

[8] https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/apr/08/italy-declares-own-ports-unsafe-to-stop-migrants-disembarking

https://timesofmalta.com/articles/view/no-more-migrant-sea-rescues-malta-tells-ngo-rescue-ships.784127#.Xo2rdUanj2g.twitter

[9] https://mobile.twitter.com/seaeyeorg/status/1247168684218552320

https://sea-eye.org/en/shots-fired-by-libyan-militia-in-the-midst-of-alan-kurdi-rescue-operation/

https://timesofmalta.com/articles/view/libyan-flagged-speedboat-fires-warning-shots-as-migrants-are-rescued.783893

[10] https://mobile.twitter.com/seaeyeorg/status/1247251731370487818

[11] https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/76022.pdf

[12] https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/09/world/europe/malta-migrant-boat.html

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/apr/10/libyan-officials-migrants-stopped-seaports-unsafe

[13] https://alarmphone.org/en/2020/05/20/maltas-dangerous-manoeuvres-at-sea/

[14] https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/30/world/europe/migrants-malta.html

https://alarmphone.org/en/2020/04/24/malta-the-ghost-fleet-against-migrants-frontex-blames-the-countries/

https://timesofmalta.com/articles/view/we-have-blood-on-our-hands.785993

https://www.spiegel.de/politik/ausland/fluechtlingsdrama-im-mittelmeer-europas-toedliche-verzoegerungstaktik-a-4ce6655f-9d49-43a8-b360-b6e44585d414

https://timesofmalta.com/articles/view/the-faces-and-names-of-a-migration-tragedy.788723

[15] https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2020/may/29/italy-considers-charges-over-maltas-shocking-refusal-to-rescue-migrants

https://www.avvenire.it/attualita/pagine/cosi-malta-respinge-i-migranti-e-li-dirotta-verso-libia-e-italia

https://www.avvenire.it/attualita/pagine/cosi-malta-sta-provando-a-fermare-l-europarlamento-dopo-le-inchieste-sui-respingimenti-illegali

[16] https://mobile.twitter.com/alarm_phone/status/1261678966378815489

https://twitter.com/alarm_phone/status/1264165125013078016?s=12

https://twitter.com/alarm_phone/status/1265387897517113344

https://twitter.com/alarm_phone/status/1265387897517113344?s=20

[17] https://data2.unhcr.org/fr/documents/download/77089

[18] https://twitter.com/alarm_phone/status/1266042928616611840

https://www.infomigrants.net/en/post/25040/98-migrants-returned-to-libya-after-being-rescued-by-commerical-ship

[19] https://mobile.twitter.com/alarm_phone/status/1257309533765918720

https://timesofmalta.com/articles/view/78-rescued-migrants-still-stranded-at-sea-on-cargo-ship.789971

https://www.nytimes.com/aponline/2020/05/04/world/middleeast/ap-ml-libya-migrants.html

https://www.infomigrants.net/en/post/24581/situation-of-migrants-on-marina-container-ship-worsening

https://twitter.com/alarm_phone/status/1258761664670941188?s=09

[20] https://www.maltatoday.com.mtnews/national/102532/libya_is_only_real_solution_to_migration_crisis_robert_abela_says#.XspfIEQzbIV

https://timesofmalta.com/articles/view/abela-ministers-return-from-libya-after-positive-migration-talks.794840

https://www.maltatoday.com.mt/news/national/102760/maltese_official_to_be_posted_in_libya_in_fight_against_illegal_immigration_#.Xti10i-w21t

[21] https://www.dw.com/en/malta-to-keep-migrants-at-sea-until-eu-acts/a-53306405

https://timesofmalta.com/articles/view/decision-to-house-migrants-on-captain-morgan-boat-bizarre-delia.789560

https://twitter.com/alarm_phone/status/1256866644430934016

https://twitter.com/alarm_phone/status/1256877513290199042

https://mobile.twitter.com/alarm_phone/status/1256928815902834689

https://timesofmalta.com/articles/view/larger-captain-morgan-ferry-deployed-for-rescued-migrants.792263

https://timesofmalta.com/articles/view/second-captain-morgan-ship-chartered-for-120-more-migrants.790556

https://aditus.org.mt/open-letter-to-eu-commissioner-johansson-regarding-the-migrants-held-on-the-captain-morgan-boats/

[22] https://twitter.com/alarm_phone/status/1262698192988188678

https://www.independent.com.mt/articles/2020-05-19/local-news/Migration-Hunger-strikes-and-attempted-suicide-on-Captain-Morgan-migrant-boats-6736223310

https://timesofmalta.com/articles/view/migrants-aboard-captain-morgan-boat-are-on-hunger-strike-ngo.793082

[23] https://aditus.org.mt/the-ill-treatment-aboard-the-captain-morgan-ships-must-be-stopped-at-once/

https://www.maltatoday.com.mt/news/national/102460/malta_gives_ultimatum_to_eu_with_threat_to_veto_irini_commanderinchief_choice#.XsWCMkQzbIV

https://lovinmalta.com/news/socially-distant-demonstrators-call-for-malta-to-take-in-captain-morgan-migrants-after-hunger-strike-reports/

https://us19.campaign-archive.com/?e=&u=2dca09f67efb6fc090574a83f&id=8d98cc5ede

https://www.evangelisch.de/inhalte/170422/21-05-2020/un-160-auf-booten-festsitzende-migranten-land-bringen

https://www.unhcr.org/news/press/2020/5/5ec664284/unhcr-iom-urge-european-states-disembark-rescued-migrants-refugees-board.html

https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/05/22/malta-disembark-rescued-people

https://aditus.org.mt/legal-update-on-the-captain-morgan-incident/

[24] https://mobile.twitter.com/alarm_phone/status/1269563944152240128

https://www.tagesschau.de/ausland/malta-fluechtlinge-109.html

https://www.maltatoday.com.mt/news/national/102799/captain_morgan_migrant_protest_four_boats_dock#.XtyIRqabFTf

https://timesofmalta.com/articles/view/three-eu-countries-have-offered-to-help-malta-with-migrant-relocation.79720

[25] http://www.mediterraneocronaca.it/2020/05/20/tragedia-sulla-moby-zaza-migrante-si-tuffa-in-mare-e-muore/

[26] https://twitter.com/alarm_phone/status/1264139308694454273

https://twitter.com/AgenziaH/status/1264504893475368966?s=09

[27] https://www.reuters.com/article/us-libya-migrants/libyas-tripoli-government-says-30-migrants-killed-in-revenge-attack-idUSKBN2342X1

[28] https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2020/06/death-toll-tunisia-migrant-shipwreck-rises-54-200612073326530.html

[29] https://twitter.com/alarm_phone/status/1271797085097070593?s=20

https://mobile.twitter.com/alarm_phone/status/1271814644634734593

https://twitter.com/alarm_phone/status/1271866100544933888

[30] https://twitter.com/alarm_phone/status/1274420972062494720

[31] https://twitter.com/alarm_phone/status/1270289539479883780?s=12

https://twitter.com/seawatchitaly/status/1270423770688339968?s=12

[32] https://twitter.com/alarm_phone/status/1270434228480729089?s=21

https://twitter.com/seawatch_intl/status/1270426393025884166

https://twitter.com/UNHCRLibya/status/1270492583966519300?s=20

https://www.aa.com.tr/en/middle-east/libya-3-more-mass-graves-unearthed-in-tarhuna/1875174

[33] https://twitter.com/seawatch_intl/status/1273298731711057920?s=12

[34] https://twitter.com/RescueMed/status/1273916614111617025?s=09