1 Introduction

This report portrays and denounces the multiple forms of criminalisation of people on the move in the Western Mediterranean and Atlantic region and the damaging effects such criminalisation has on people’s lives. However, we have to start by expressing our grief and anger about the events of 24 June, when dozens of people – although the first estimates were 29 dead, the estimated number of dead and/or missing people has now risen to over 100 – were killed by Moroccan and Spanish forces at the Melilla border fence. Alarm Phone among many other collectives and organisations joined the AMDH statement (see section 3.1).

The massacre of 24 June clearly shows what lies behind all the forms of criminalisation described by the report: the dehumanising legitimisation of brutal violence that ends lives cruelly and deliberately. The events of 24 June are, as the people on the move have long understood it, part of an outright war against people who exercise their right to move freely in the regions of the Western Mediterranean and the Atlantic. To do that, if you are racialised, you must resist state-imposed discrimination, illegalisation, deportation, detention, imprisonment and violence. This report shows that the implementation of these practices was ramped up after the Spanish government endorsed the Moroccan occupation of Western Sahara in March.

We point out a variety of means and strategies that are used to instrumentalise, exploit and brutalise people on the move once they have been framed as criminals. To name some of those practices:

Firstly, there are laws that serve to punish any entry or exit to and from a country without registration, like Article 25 in the Spanish foreigners’ law defining the requirements for a (‘regular’) entry into the Spanish territory or the Algerian law from 2009 punishing the ‘illegal exit’ of the Algerian territory with a two to six-month sentence and a 20,000 to 60,000 dinar fine (see section 3.5). Secondly, there are the trials against and imprisonment of alleged captains which are not based on any tangible evidence. In any event, a captain is no more than the brave soul who took responsibility for navigating the boat after departure. These spurious prosecutions are meant to serve as cautionary examples. Individuals steering the boats are being made responsible for the life-threatening journeys they are forced to make by the same states that actually bear the responsibility for endangering these lives (see section 3.2).

Thirdly, once inside a state’s jurisdiction, there are strategies to deny or allow access to public infrastructure, to deem a person ‘legal’ or ‘illegal’. One such example is the Moroccan residency card (carte de séjour) (see section 3.3).

These practices serve to give apparent legitimacy to violent state actions, such as the massacre on 24 June, or the assassinations of people who were allegedly involved in organising trips in Algeria (see section 3.5), the forced relocations within Morocco to the Algerian border zone (see section 3.4), or imprisonment in Morocco where people are completely cut off from the outside world and denied visits even from their closest relatives (see section 3.1). These practices prevent access to basic human needs. They force you into precarious situations where you are further brutalised or exploited by non-state actors (see e.g. section 3.3).

These categories of criminalisation and the ways they are implemented by state actors are arbitrary. They are also instrumentalised in political bargaining with completely different goals. The connection between the U-turn of the Spanish policy regarding the Western Sahara and Moroccan and Algerian ‘migration’ policies makes this clear. Their arbitrary implementation is central to the instrumentalisation of people on the move in the hope of achieving geopolitical goals unrelated to the reality of migration. One way this happens is using people’s desire to move country to exert ‘pressure’ on neighbouring states by allowing, for a short time, or preventing, if possible, border crossings. People on the move are framed as a ‘weapon’, thus further dehumanising real people with the human desire to rebuild their life somewhere new.

We will continue to document, denounce and organise against all these unnecessary and deadly forms of criminalisation.

Our report draws from different sources. We gather information as people reach out to us via the Alarm Phone number. Various local Alarm Phone (AP) groups in the region document their observations and information on the site. We are aware that we do not have a complete overview of what is happening on the Western Mediterranean and Atlantic routes. Whenever we could, we linked sources to newspapers and other articles. But not everything we report on is documented in the media. All information without reference stems from activists in the regions.

2 Sea crossings & statistics

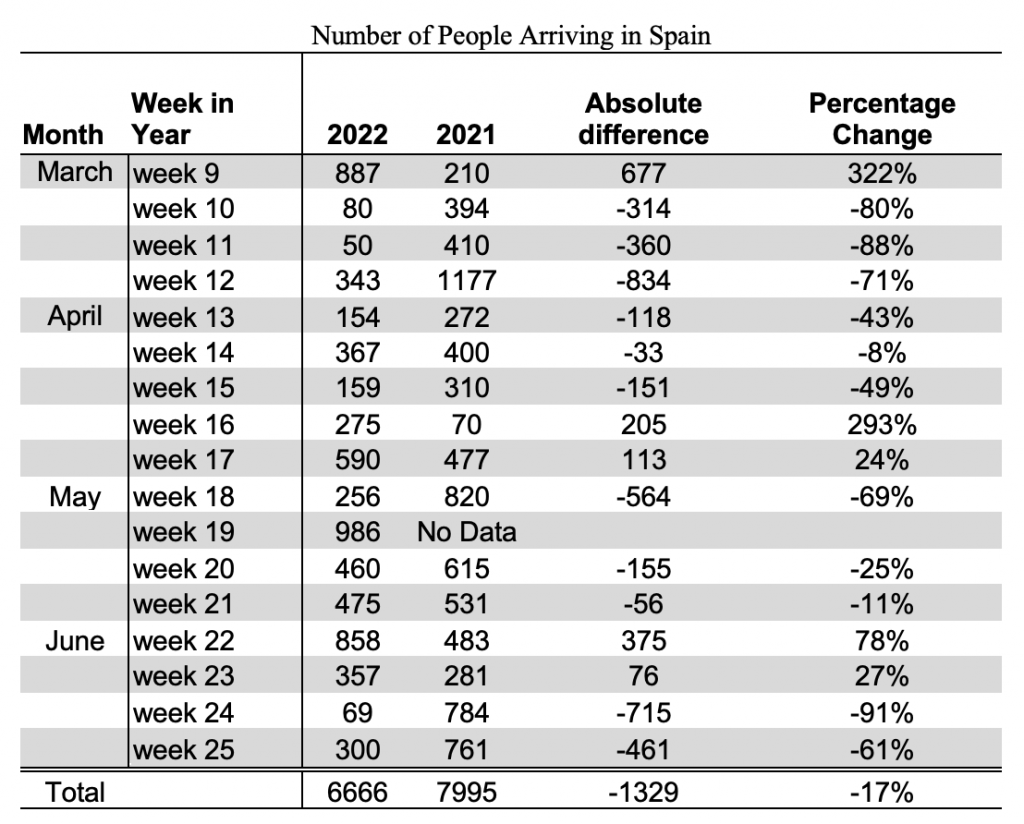

In the period from March to June 2022, Alarm Phone was in contact with at least 1,675 people on board of 43 boats on the Western Mediterranean and Atlantic route. Given the UNHCR registered 6,666 arrivals in Spain for the same period, this means approximately 25% of people passing through this route were in contact with Alarm Phone.

Overall, there were many bozas (‘boza’ is a Bambara word meaning ‘victory’; it has passed into the argot of the Western routes to describe a successful arrival). In total, however, there were 1,329 fewer crossings this year compared to the March – June period last year. This represents a 17% reduction in crossings for the period (see table).

Source: Alarm Phone, based on UNHCR statistics

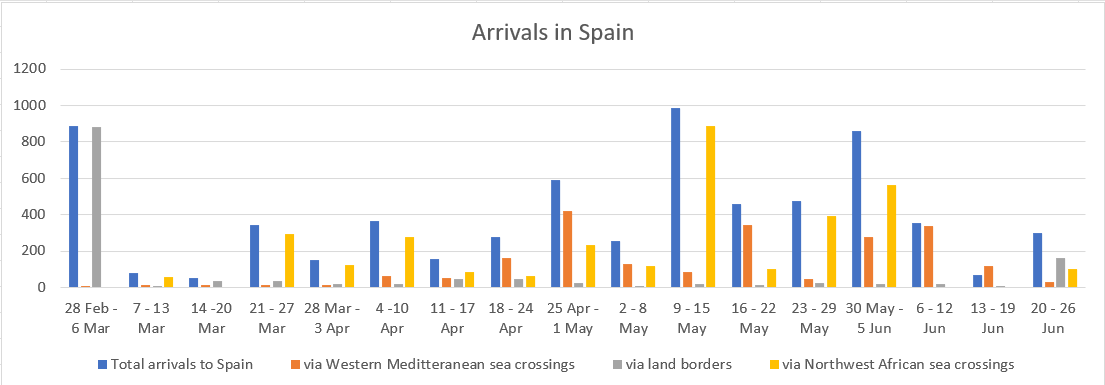

In March and April, Alarm Phone was involved in 14 cases. In May, it was 20 boats (five of them on 31 May). In June, 9 boats reached out to Alarm Phone. This increase in Alarm Phone cases reflects a general increase in crossings in May (see graph).

Total arrivals in Spain. Source: Alarm Phone, based on UNHCR statistics

As the graph shows, the majority of crossings were via the Northwest African route to the Canary Islands. This reflects a general shift to this more dangerous route with the intensification of border policing in the north of the country. This is a development which we have already analysed in several previous reports. There were, however, three weeks in which the Atlantic was quieter than other routes.

The Western Mediterranean sea crossing was the most frequented means of entering Europe in the final week of April with 421 successful entries. There were more recorded bozas on this route during this week (421), and slightly fewer than typical on the Northwest African crossing (235).

Out of 11 boats that called us from the Strait of Gibraltar and the Alboran Sea, seven reached peninsular Spain, mostly arriving in Motril and Tarifa. Another boat that had departed from Algeria also arrived safely on the Spanish mainland.

Most of the calls we received came from the Atlantic region, reflecting both the more frequent use of this route and its more dangerous nature. Out of 31 boats that called us, 17 boats reached the Canary Islands. However, nine boats were intercepted whilst it was reported that two returned by themselves. In addition and very sadly, we were informed about three tragic shipwrecks. Between them, there are at least 100 people dead or missing (see also chapter 4: Shipwrecks and missing people). We are not only saddened, but also angry. We want to express our condolences and solidarity with all family members and friends of those who are no longer with us due to the incessant, murderous border regime.

The first week of March 2022 saw the largest ever coordinated rush on the border fences at Melilla with 871 successful entries.

In the final week of June, 133 people on the move, many moving from Sudan or South Sudan, also managed to overcome the border fences at Melilla in an attempt that was met with extreme police violence that, according to official Moroccan statistics, left at least 23 people dead . Caminado Fronteras calculates that at least 37 people lost their lives, but given the huge number of missing people, the number may well be in the hundreds (see section 3.1).

3 News from the region

3.1 Nador

The last week covered by this report on developments in the Nador region was marked by unprecedented violence at the border zone and in the surrounding forests. Starting around 20 June, the Moroccan forces ramped up the violence in their attacks on the communities of the people in the forests. It left a large number of injured people in the woods. The raids in the forests extend to camps very far from the border fence on Gourougou mountain. It seems that the Moroccan strategy is to try to clear the area once and for all in order to thwart border crossings at the fence. The people were not only chased and had to endure many days without sleep, but they were also forced to fight back.

On 24 June, another massive collective attempt to overcome the border resultded in extremely violent attacks on those who made the attempt. They were at an unprecendented level, even for this brutal region. During the attempt, an unknown number of people on the move and two Moroccan agents died. Officially communicated numbers start with 18 dead, but the estimations made by our contacts in the forests suggest that about 130 people died during the clashes.

Around 2,500 people had tried to reach the fence, fighting against the Moroccan forces that tried to prevent them from accessing the barrier. According to Spanish media, a group of more than 500 people eventually managed to break the access door of the Barrio Chino border checkpoint with a bolt cutter and began to enter Melilla by jumping over the roof of the checkpoint. 133 people managed to enter the Spanish enclave succesfully.

Many of the remaining people were arrested by the Moroccan forces, severly injured, and grouped together without medical assistance for up to 9 hours. Even for this border zone, which has seen brutal violence stretching back over decades, the extent of the violence of 24 June and well attested neglect of seriously wounded people is shocking in the extreme.

Nador Intercepted and Injured. Source: AMDH Nador

We issued a press release jointly with AMDH and other local and international organisations. Together we made a number of demands, including the opening of an independent judicial inquiry on both the Moroccan and Spanish sides, as well as at the international level. We also demand the identification and repatriation of the dead. This was in response to the authorities having buried the bodies quickly and anonymously. It is thanks to the work of AMDH that it is known that the Morocan authorities started to interment the bodies of the dead. They were monitoring the situation and report that on 26 June 21 graves were dug at the local burial ground.

Graves Nador. Source: AMDH Nador

On 26 June, several executives of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Ministry of Interior held a meeting with the ambassadors from various African states to discuss the incident. It was extremely disappointing for the communities concerned. The ambassadors mainly condemned the crossing attempt and accepted the legitimacy of the violence deployed by the Moroccan forces. There was no pressure for identification of the deceased nor for an independent investigation of their deaths.

Hundreds of people were arrested during the clashes and, by and large, brought to a closed military camp in Selouane. Once there, you can expect to wait to be tried, deported to your country of origin or forcibly relocated to the South of the country. Our local team in Oujda informed us that trials of 69 migrants arrested after the massacre in Nador were launched on 27 June. The trials are being conducted in two groups. One is against 33 people who are being prosecuted in the Court of Appeal (postponed to 13 July). In the other, a group of 36 people are being prosecuted for first instance offences (postponed to 4 July); they are all in pre-trial detention.The first group is being prosecuted for serious charges, “disobedience, violence against security forces, forest fire, deprivation of the liberty of a public servant, armed violence, participation in an organised gang with the aim of irregular immigration”. We will follow up on the outcome of these trials and report on them in our next issue.

At the end of our last report period, we witnessed massive collective jumps over the barriers surrounding the Spanish enclave Melilla. They happened on 2 and 3 March, fortunately with a less lethal outcome:

On 2 March, an estimated 2,500 people, mainly nationals from countries south of the Sahara living in makeshift camps in the Gourougou forest, organized collectively and ran towards the fences. Around 500 people managed to cross and were taken into the CETI (Centro de Estancia Temporal de Inmigrantes / Temporary Stay Centre for Immigrants) of Melilla. According to observations of the AMDH Nador, 50 others who managed to jump the fence were illegally pushed back by the Spanish Guardia Civil. Around 200 were arrested by the Moroccan forces and brought to the detention center in Arekmane.

On the following day, another massive attempt followed. This caught the authorities off guard. Estimates of the number of people who made the attempt reach as high as 1,200. Around 350 managed to reach the CETI in Melilla. During this attempt, RTVE Melilla was able to film a young man being violently beaten down from the fence by the Guardia Civil. He was eventually pushed back and arrested by the Moroccan police. AMDH managed to reach out to him, and he gave testimony:

“I was severely beaten and sprayed with tear gas. The blows of 5 guardia civiles were coming at me from all directions. Wounded, I had no care in Melilla. They gave me to the Moroccan military who took me to the centre of Arekmane instead of the hospital of Nador. (…).”

Following these massive jumps, large-scale raids were conducted over the next days in and around Nador to arrest and push many Black Africans away from the border zone. Those who were chased but escaped are exhausted. Those arrested were brought to the far South, even as far as the Algerian border.

The fences of Melilla (and Ceuta) are being reinforced yet again. This time at a cost of €4.1 million. Eulen, the designated company, will review and repair spaces such as the command and control centres and patrol posts. They will also work on the lighting network, fences and field equipment.

The remaining group of people could find no logic as to which of their arrested comrades were eventually forced south within Morocco, which were deported to their respective country of origin, and which remain, seemingly forgotten about, in prison.

It is not easy to visit and support detainees. Some of the arrested have been accused of being the organisers of the big collective jumps at the beginning of March. Our local friends are trying to follow up on the cases. They are in contact with detainees from Mali and Guinea who were arrested during the April raids.

The cases being made by the prosecutors as to who was behind the jumps are unclear. Local contacts assume that, as always, a random number of people were picked as scapegoats after being profiled with criteria such as dreadlocks or longer beards. The assumption here is that facial hair or locks indicate that someone has been in the forests for a long time.

In general, people on the move have been treated as criminals for a long time in the region around Nador. But this has recently gone up a level. According to the local Alarm Phone group, people now fear years of prison for every thwarted attempt to overcome Spanish maritime or terrestrial borders.

Many of the detainees have no lawyers or any other form of assistance. They do not know what they have been charged with. They are not even allowed to make phone calls. Our local comrades have tried to contact the respective embassies many times, but they do not engage. Some of the detained are traumatised to the point of memory loss and suffer from their experiences once they are released. Families that thought their loved ones had died are being retraumatised when they discover that, in fact, their relatives had been in detention but had simply not been allowed to communicate.

It is very difficult to visit imprisoned people. This is often the case even for their family members. The Moroccan prison administration requires that a family member must have a valid residency permit in order to visit a migrant detained in a Moroccan prison. This requirement often renders a visit impossible in view of the difficulties Black Africans have in obtaining or renewing a residence permit in Morocco.

For Moroccan nationals who try to flee the country, criminalisation is also a threat. For example, on 6 June, seven Moroccan fishermen were arrested by the Spanish Guardia Civil while fishing in their usual zone off Béni Chiker. Their two boats were forcefully brought to the port of Melilla, and the fishermen are still under arrest. They are being charged with human trafficking, as the Guardia Civil assumed that one of them, who had fallen into the sea, wanted to reach Melilla.

Unfortunately, we cannot provide deeper insights into the criminalisation of Moroccan nationals, but we are working on extending our network and knowledge to report more from the Moroccan harraga-perspective in future.

3.2 Atlantic Route

Crossings and political changes

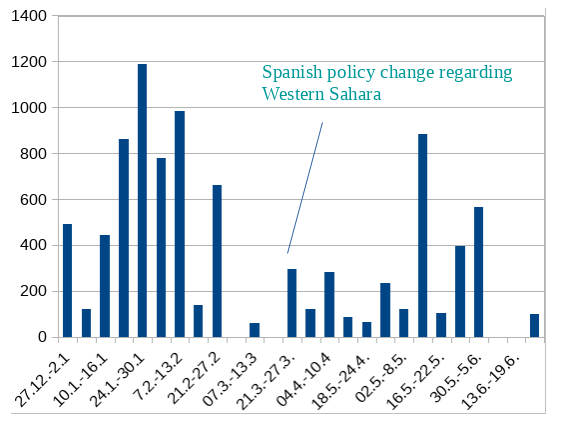

In the past months, talking or writing about the Atlantic route and the numbers of departures and arrivals on the Canary Islands has inevitably brought up one major political event: the Spanish policy U-turn regarding Western Sahara. Until mid-March, relations between the governments of Morocco and Spain were rather strained (especially after Polisario leader Brahim Ghali received medical treatment in the Spanish state in 2021; we covered the event in a previous report). Everything changed when the Spanish government announced on 18 March that it would now support the Moroccan “autonomy plan” for the “Saharan provinces”. This is no less than a de facto recognition of the Moroccan occupation of Western Sahara. Since then, the governments of Spain and Morocco have shown enthusiasm for the new-found cordial relationship, as they both expect a range of economic benefits, for example by trying to thereby legalise the exploitation of mining, fishing, agriculture and other natural resources (e.g. sand). However, Spain also hopes to curb migration by implementing a series of measures in cooperation with the Moroccan state.

On 22 March, only a few days after the policy U-turn was announced, deportations to Morocco resumed. The Spanish minister of the interior is concocting plans to deploy Spanish staff on Moroccan patrol boats. This is already the case in Mauritania and Senegal. The purpose is, of course, to intercept more people on the move. At the time of writing, bilateral negotiations between the Moroccan and Spanish governments revolve around maritime spaces between Western Sahara and the Canaries. As Alarm Phone, we believe this will result in the vast extension of the Moroccan SAR (Search and Rescue Zone) off the shores of Western Sahara, adding another massive obstacle to the freedom of movement in the Atlantic. This would be particularly worrying as the Moroccan authorities have repeatedly demonstrated their unwillingness to carry out a safe and fast rescue – often at the cost of human lives.

On the ground, the Spanish policy reversal has already had very concrete effects. As Alarm Phone member B. reports, raids and arrests have increased since mid-March, especially when a good weather forecast makes departures more likely. In Laayoune particularly, the Moroccan authorities seem unusually keen on preventing departures by carrying out what they call “Operation Sanitisation” (“opération assainissement”), arresting Black people in their houses and driving them hundreds of kilometres away.

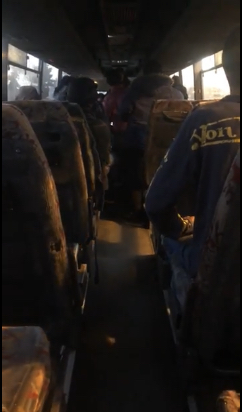

Moroccan police officers in the course of a so-called “sanitisation” operation in Laayoune, as witnessed by a deportee sitting in a bus. Source: Alarm Phone

The Moroccan authorities have also increased their efforts to intercept people on the move right at the departure points. They have also taken to making these efforts known to the media. For instance, 236 people were prevented from leaving the shores on 25 and 26 March, 231 people were blocked on 29 and 30 March around Laayoune, and 133 people were frustrated on 1 and 2 April near Dakhla.

According to the Spanish newspaper La Vanguardia, government sources report that high numbers of arrivals throughout the winter have been a prime example of Rabat instrumentalising migration flows and using them as a key point of pressure to obtain Spanish support for Morocco’s occupation of Western Sahara. Correspondingly, Spanish officials then recognised the major role Morocco was playing in reducing departures, which some right-wing and nationalist media framed as a positive development: The head of the national police on the Canaries conceded that Morocco was controlling the departure zones more meticulously, as only 375 arrivals were registered in March 2022. The minister of foreign affairs cited a 45% decrease in arrivals thanks to Moroccan cooperation.

However, we believe the situation is more complex. Departures in March had already dropped significantly before the policy change was announced and surged again in May. We as Alarm Phone think that an increase in Moroccan securitisation has exacerbated the situation for the people on the move, but does not make travelling impossible; people now seek other depature points than Western Sahara. Furthermore, adverse weather conditions and the jailing of some smugglers have also contributed to the up and down of arrival numbers.

Arrivals on the Canary Islands until the end of June, showing an up and down of crossings. Source: Alarm Phone, based on UNHCR statistics

As Alarm Phone, we strongly condemn the fact that the Spanish government agrees with the instrumentalisation of migratory flows and surrenders to Morocco’s economic desires by exchanging Western Sahara and repressing the Sahrawi population in a neo-colonial way. More controls and greater repression will not prevent people from using their right to seek safety and a future elsewhere. Attempting to close down one route for migrating to Spain or Europe will only open or strengthen routes elsewhere. Already, many people do not start from Morocco or Western Sahara to reach the Canary Islands. They start much further south, in Mauritania or Senegal. Shipwrecks or boats adrift on these long journeys are frequent, such as the shipwreck with 55 people picked up by a Mauritanian warship 74 km off the coast of Mauritania in early May, or the fatal shipwreck that occurred in the south of Senegal in late June, with 91 survivors, 13 confirmed dead and around 40 people missing.

Rescue operation near Kafoutine, Senegal, where a boat with nearly 150 passengers en route to the Canary Islands shipwrecked after a fire on board. Source: Alarm Phone

Criminalisation in Morocco and Western Sahara

On both sides of the Atlantic, those on the move are treated as heinous criminals, through laws prohibiting “irregular” exit or entry and the criminalisation of those who organise unauthorised journeys. As shown above, Moroccan authorities are currently actively trying to prevent interceptions and arrest people in the move at the site of departure. Alarm Phone activists explain:

“When this happens, certain migrants are accused of being responsible for the journey and being captains […]. They are taken to a police station, and the matter is investigated without the aid of a lawyer and without translators to explain their rights, because their rights are a joke. They are then taken to the judge and accused of being a smuggler or part of a trafficking network. They are given hefty sentences of 10 to 15 years in prison.”

Alarm Phone activists document human rights violations and try to facilitate legal and medical support for those in prison:

“In the southern provinces, there are now roughly 50 people in prison charged with having driven a boat or organised illegalised migration. As Alarm Phone, we have tried to support three migrants who were arrested only because they were wearing a wristband with the Alarm Phone number. […] There are also seven sub-Saharan people who received hefty prison sentences: four Senegalese were condemned to 10 years, an Ivorian to 15 years and two Guineans, one got 20 years because it’s a smuggler who had been investigated for years, the other 10 years. […] They are living a very difficult situation! We are calling on African governments to have their own citizens extradited. They are all sick and receive low-quality food in prison.”

The Spanish policy U-turn on the issue of Western Sahara also seems to have given the green light to the Moroccan judiciary to apply harsher sentences:

“Before, you were able to get your sentence from the first instance reduced on appeal. Unfortunately now, the condemned do not even take a lawyer anymore to the appeal because they know the judge won’t even listen to them. Since the start of the pandemic, the verdicts have also been delivered via video-conference.”

Criminalisation in the Canary Islands

The (often arbitrary) criminalisation of boat drivers is also a major issue once arrived in the Canary Islands. If a drone captures somebody touching or handling the engine, that person will be accused of being the captain and thus responsible for the smuggling operation. According to Article 318 bis 1 and 3b of the Spanish penal code, prison sentences vary depending on the circumstances of the journey. This means that any injuries, bodily harm or deaths are taken to aggravate the ‘offence’ and lengthen the sentence. In the latter case, people may then be charged with homicide. This is a complete reversal of who is to blame for the numerous deaths at sea.

It is often the case that passengers who do not have enough money to buy a journey are asked to drive the boat, especially when it is within range of the Spanish authorities. If they carry money with them, this may also be used as “proof” that they were involved in organising the journey. Furthermore, other passengers may be told by the Spanish police that snitching on the captain will increase their chances of remaining in Spain. This is no more than a blatant and dirty strategy by the authorities to manipulate people into criminalising their comrades.

Apart from sentencing boat drivers, Spain has a general tendency to treat people on the move as criminals; a habit they share with many other European countries. Some are taken to the deportation prisons (like the CATE, Centro de Atención Temporal de Extranjeros, in Barranco Seco, Gran Canaria) right upon arrival, without any proper legal assistance, translators or access to the necessary procedures to ask for international protection. It is much harder to ask for asylum once in prison. In early May, a hunger strike was organised by CIE (Centro de Internamiento de Extranjeros) inmates in Gran Canaria because of the physical and psychological mistreatment they suffer there. This strike was accompanied by several escape attempts in early and mid-May.

There has also been lots of interference by the authorities when people tried to self-organise, plan demonstrations and show acts of solidarity. As early as 2021, in an internal communiqué, comrades from Tenerife reported police harassment during demonstrations in the city of La Laguna, not far from the Las Raíces and Las Canteras camps. They also reported stop and search measures and racial profiling targeting those presumed to be migrants. Additionally, the repressive, right-abnegating “ley mordaza” (gag law – see also a previous AP report) was used repeatedly to impose fines on activists working in solidarity with those on the move or on human rights journalists: Most recently, the ley mordaza was used to impose a €800 fine on a Pulitzer Prize-winning photo journalist for taking photos in the Arguineguín harbour in December 2020.

3.3 Tangier

Heavy policing is a constant feature of life for people racially profiled as ‘black’ and criminalised as ‘illegal migrants’ in Tangier. Nonetheless, in March 2022 local Alarm Phone activists reported an intensification of police patrols, street arrests, and forced expulsions from the city, as Morocco and Spain re-entered negotiations over border-enforcement co-operation.

Migrant groups living in the forests on the outskirts of the city noted an uptick in the number of police raids to three a day – morning, afternoon, and evening – encouraging many to leave their sleeping spots with their important belongings early in the morning, and to only return late at night to minimise the chance of arrest.

Meanwhile, groups and individuals without residency status, who are trying to integrate into Tangier’s city life, also registered an increase in police roundups and mass deportations to the south of the country, including of women and children, which was previously rarer.

No one knows the total number of arrests because the paramilitary wing of the Moroccan police, the Auxilary Forces (forces auxiliaries), operates without significant legal oversight or public scrutiny.

Indeed, during his own deportation in March, a local activist exposed the fact that migrants were being ‘sorted’ in an informal centre before boarding buses to be forcibly moved to Casablanca, Tiznit or Beni Mellal without any official identification:

“We are not asked for our identity, people take our picture with their phone. If one of the migrants refuses, he can be beaten up. We do not know where these photos are going and why they are taken.”

Following mass killings at the borders of Nador on 24 June, there have been further police clampdowns: police are currently stationed in transit hubs to prevent Black Africans without residency status from re-entering Tangier, as part of a police program that will reportedly last two months.

The constant threat of EU-funded police violence institutionalises conditions whereby Black Africans without residency status are rendered especially vulnerable to abuse and attack. For example, AP activists). On 8 March, a Cameroonian trying to escape the same Auxiliary Forces fell on rocks and lost three teeth (reports from local AP activists). We are told that, as he was unable to afford the cost of surgery, he was unable to eat solid foods for over two months. A Cameroonian man was also robbed of his phone and other possessions after being caught by a gang and attacked with knives after having to flee the Auxiliary Forces (reports from local AP activists).

There have been further reports of people without status being targeted for organ trafficking in the city. Many feel their respective embassies don’t support paperless migrants in Tangier but are only interested in the wealthier students enrolled in the university in the city. The constant threat of arrest means EU-funded Moroccan state agents are instrumental in creating the conditions for these attacks.

At the same time, individuals wishing to regularise or renew their residency status struggle to do so. Restrictions on access to the Carte de Sejour residency card have increased following legislative changes announced by the new government of Aziz Akhannouch and brought into force at the start of this year.

Consequently, growing numbers of people are or are on the brink of being criminalised. This includes those who previously had regular residency status and wish to renew it. “If many people in a migration situation are undocumented, it is not only their fault“, a group of migrant artists explain via a public alert. “Many want to live in Morocco and are refused papers.”

The combination of legal restrictions and violent policing has created a situation where, according to Alarm Phone activist K.: “What happened to us has made us live in fear! Our stress level has unfortunately doubled.” The seemingly arbitrary nature of arrests leaves many wondering whether they are wanted in the city or not. Some simply ask for clarity so they can plan their lives accordingly.

“The governor of the region and other credible authorities should give us an ultimatum with a specific deadline for us to evacuate and take our few belongings out of the city of Tangier, out of the northern region! and maybe outside the Kingdom of Morocco in general, if this will always be the case!” demands K.

In a public statement denouncing ongoing arrests, artist Salvador Tomnyuy calls out “extreme hypocrisy”, where “the authorities talk about us holistically in front of cameras and then go behind the camera to mistreat us”.

Even long-term residents and well-known contributors to the cultural life of Tangier have been targeted, such as the musician Moussa from the group Farafina, currently in residence at the Institute Français.

Another artist and Alarm Phone activist explained in a video he released during his own deportation how the Auxiliary Forces detain Black migrants for no reason: “We live, we work, we apply for residency, and they deny it. They take us from our homes, they attack us…They treat us like to animals, without any respect, without any consideration”.

A view within the bus (top) and of the seats (bottom) filmed by an Alarm Phone activist and member of the collective SHU MOM Art.

Tangier residents have spoken up to denounce the violence, often at great personal risk (see additional reports here and here).

A petition was launched to stop the arrests. “The young Africans living in Morocco and Tangier are already at home,” it explains. “The repeated roundups and deportations are in no way justified. Instead, help them to regularise their status. The hunt for Africans is a disgrace.“

3.4 Oujda and the Algerian borderzone

Alarm Phone Oujda reports that recently more people have been crossing the Algerian border into Morocco. As we pointed out in our last report, these border crossings are highly dangerous and the criminalised drug trade relies on people’s need to cross the border. So drug trafficking has also increased because the two phenomena are related. As so many people will never, under the current system, be granted permission to enter Morocco, they must rely on those outside the law with the power to assist them. Their need renders them vulnerable to exploitation as a drug mule. This is especially true of minors and women, who must pay more to cross the border (see our previous report) and thus have fewer options. Running drugs, of course, increases your risk of criminalisation and further exposes you to some of the most dangerous parts of society.

The criminalisation of people on the move has also increased. According to Alarm Phone in Oujda, Moroccan police accused a Nigerian man of being the head of a smuggling ring assisting people to cross the border. In addition, eight people, including an Algerian national with irregular residence status in Morocco, were accused of drug trafficking across the Algerian-Moroccan border.

Furthermore, pushbacks to the border area continue to be reported. Even in Laayoune, in the south of the country, people were put on buses and taken to and then across the Algerian-Moroccan border in the Oujda region.

The authorities of the city of Nador forcibly removed around 40 people of varying nationalities to Oujda on 17 June 2022. What they had in common was irregular residence status. According to information from AP Oujda, eight people fled the bus after breaking the vehicle’s windows. The incident occurred in Garbouz, about 30 km north of the city of Oujda. The search for the people who escaped the bus is ongoing.

Since 18 June, groups of Sudanese and South Sudanese asylum seekers have been displaced from their assembly points in the town of Oujda. During the week of 20 June, seven Sudanese people were arrested by police, and there is a general campaign to arrest illegalised migrants. Since mid-June, arrests have been increasing and migrants are in hiding to escape the police. They live in a very precarious situation and are forced to have their bags packed and ready at all times so as to escape the police. One of the Sudanese witnesses told us that there are always forced removals to the Algerian border and to other cities like Casablanca. AP Oujda is in active exchange with AMDH Oujda and Nador to get more information about migrants sent back to Laayoune.

AP Oujda reports that in the period from April 2022 to June 2022, approximately 1,500 people came to Oujda across the Algerian-Moroccan border, including 25 women and 146 minors of different nationalities. Six people were injured at the border.

After the killings in Nador, the severely injured were taken to CHU Oujda hospital. The migrants are under police surveillance, and no one has access to the injured. Several organisations tried to check on them, but at the time of writing it has been impossible to gain access to them in the hospital.

3.5 Algeria

Note: In Algeria, there are no Alarm Phone teams and activists, only contacts and friends of friends, so the information in this section is based on a small local network and reliable media articles.

The political and migration context in Algeria in recent months has been marked by the outbreak of an unprecedented diplomatic crisis with Spain regarding the territory of Western Sahara. In March, when Spain made public its support for the Moroccan autonomy plan for Western Sahara, the deportations of Algerian citizens who entered Spanish territory without authorization by the Spanish government were immediately suspended. More recently, on 8 June, Algeria decided to suspend the treaty of cooperation (“traité d’amitié”) with Spain that has linked the two countries for the past 20 years. It put an abrupt stop to cooperation on the “management of migration flows”. This diplomatic rupture has major political and economic consequences. It has ramifications not only in Spain, but also in the EU (for more details, see this article in the media Algeria-watch). It is already affecting many Algerians who use the sea route to the Spanish mainland.

However, the period covered by this report didn’t show any signs of discouragement among the harraga. This is despite the ever growing risk of the routes towards Spain, the strength of the repression of the harraga and the criminalisation to which they are subjected. These last two topics, specifically addressed in this report, are deeply interconnected with the growth of border business organisations in Algeria, as detailed in our previous regional analysis. It cannot be said enough that, in Algeria, a law from 2009 punishes the “illegal exit” of the national territory with a two- to six-months sentence and a 20,000 to 60,000 dinar fine. Leaving Algeria without state approval has itself been made a criminal offence.

Crossings

Tracking and mass deportations of people from south of the Sahara

According to Alarm Phone Sahara, a huge percentage of these deportations occur between Algeria and Niger. 1,693 people were deported just over two days, on 20 and 22 March, to a place called Point Zéro, 15 km away from the city of Assamaka in Niger. Medical care and food provision for the deportees are effectively non-existent.

4 Shipwrecks and missing people

In the period of this report (March to June 2022) we counted more than 300 deaths and several hundred people missing, based on Alarm Phone cases and media reports in the Western Mediterranean Sea and the Atlantic route. Alarm Phone bore witness to at least three shipwrecks and cases of death due to a delay in rescue or complete non-assistance. Despite all of our efforts to document the dead and missing, we can be sure that the real number of people who have died at sea in the attempt to reach the EU is much higher.

We demand safe passage and freedom of movement for all people in order to stop the deaths at the borders and at sea!

On 11 March, a dinghy that left Tarfaya with 54 people on board capsizes. Only four survivors and five bodies have been recovered.

On 13 March, at least 44 people die in a shipwreck off the coast of Tarfaya, Morocco. The boat carrying 61 people, including 16 women and seven babies, capsized while trying to reach the Canary Islands, Spain.

On 17 March, seven people are missing and three dead bodies are recovered after a shipwreck off the coast of Ghazaouet, Algeria. The families of Atigui, Sobiane, Messaoudi, Hafed and Brahmi demand that the competent authorities speed up the search for their missing children. The article also states that in the beginning of March two dead bodies were found on the beaches of Ghazaouet.

On 19 March, the body of a young man is found at the Ghazaouet beach in Algeria. In the media there are different theories about the cause of his death. Perhaps he tried to reach Europe by boat. Perhaps he tried to swim to Melilla, Spain.

On 22 March, eight young men die in a shipwreck off the coast of Ghazaouet, Algeria. The dead bodies of three people disappeared.

On 23 March, a boat arrives in El Hierro with one corpse and two people in a critical condition. A few days later, survivors confirm the loss of 26 people at sea. The boat had left on 19 March from Mauretania.

On 24 March, a boat with at least 47 people, which left Mauritania for the Canary Islands, disappears.

On 27 March, two people drowned after their boat capsized off the coast of Tarfaya, Morocco.

On 7 April, the remains of two people are washed ashore at Akhfennir, Tarfaya, Morocco after their boat capsized. The number of the people missing or survivors of the shipwreck is unknown. Two victims are later identified as Osama and Murad and buried at the cementery of Aforar. Three more dead bodies (two of them young women) are brought to the mortuary. According to the media, about 47 people are arrested for “clandestine migration”.

On 10 April, a boat with 17 people on board is located 83 kilometres south of Gran Canaria by Salvamento Marítimo. Two of the passengers had already committed suicide by jumping overboard because they couldn’t withstand the desperation of an unjustifiable wait for rescue. The survivors spent nine days adrift at sea.

On 26 April, 27 people, including 13 women and six babies, die in a shipwreck 245 km south of the Canary Islands. The boat carried 61 people and probably capsized just as the rescue vessel came into sight.

On 26 April, six people are reported dead. The people have been calling the authorities for help since the day before, but rescue was so delayed that when the NGO Caminando Fronteras raises the alert on Twitter the boat is still adrift.

On 26 April, a dead body is found among the approximately 200 people the Moroccan Royal Navy intercepts on their way to the Canary Islands.

On 30 April, the dead body of a minor is found floating in the waters of the South Dock of Melilla, Spain.

On 7 May, 55 people are rescued after a shipwreck 74 km off the Mauritanian coast. There is as yet no access to information concerning the dead and missing.

On 8 May 2022, three young Moroccans from the city of Oujda leave the beach of Saidia on a jet ski. According to relatives, the missing people are arrested by the Algerian coast guard off the coast of Oran, Algeria (AP Oujda).

On 8 May, at least 44 migrants and refugees drown when a boat with 56 people on board capsizes off the coast of Boujdour, Western Sahara. Twelve people survive the tragedy.

On 9 May, Alarm Phone is informed about a missing boat on the Atlantic route. 13 people are rescued by the Spanish coast guard when their boat is found 120 km south of Gran Canaria, Spain. 28 people die in this shipwreck.

On 10 May, eleven people die when their boat capsizes off the Algerian coast of Tipaza. According to the news, five people survive the tragedy.

On 13 May, the organisation Caminando Fronteras reports a boat sinking with 58 people on board off the coast of Cape Boujdour, Morocco. The fate of the people is undocumented.

On 13 May, a boat with 15 people on board is rescued about 140 km south of Gran Canaria; one person is found dead.

On 14 May, a boat with twelve people on board which had disappeared one week earlier in the Alboran Sea is located with four survivors and eight dead.

On 15 May, a boat which left Tan Tan with 59 people (14 women and six children) a few days earlier is rescued by the Moroccan Navy. 46 people, including ten women and two children, survive, eleven remain missing and two people are found dead.

On 15 May, eleven people drown at sea, while five people are rescued and five others go missing near the Spanish coast. According to the media, 21 people left from the Tipaza area heading for Spain, and the overloaded boat sprung a leak and sank. The captain of a merchant vessel noticed the floating bodies and informed the Algerian coast guard.

On 31 May, a new tragedy on the Canary route with a total of 61 dead and 17 survivors is reported by Alarm Phone members.

On 3 June 2022, a boat of thirteen people sinks at 7 pm Algerian time. Three bodies are found. The others are still missing at sea (AP Oujda).

On 8 June, a boat with 16 or 17 people on board capsizes off the coast of Cape Cope, Águilas, Spain. A child and two adults die in this shipwreck. Another person remains missing.

On 9 June, Salvamento Marítimo picks up two small boats south of Formentera in the Balearic Islands. One of them contains a corpse. The boat with the dead body on board had been reported missing nine days earlier. It carried eight people, five of whom survived. The other two passengers are reported missing.

On 11 June, a dead body is found floating in the sea close to the border of Benzú, Ceuta, Spain.

On 15 June 2022, a body is found in the neighborhood of Umm Taboul, Algeria. The body is identified and taken to the morgue (AP Oujda).

On 26 June, a shipwreck occurs off the coast of Kafountine, Senegal. According to media, a fire is the cause of the accident. At least 15 people are reported dead, 87 survivors are rescued, but witnesses report that around 150 people were on board, and so dozens of people are missing.