Welcome to Europe. Source: Fatou, AP Morocco

Content

1 Promotion of migration – the crossings of May 2021

2 Sea crossings and AP experiences

3.1 Atlantic route

3.2 Tangier and the Strait of Gibraltar

3.3 The enclaves: Ceuta and Melilla

3.4 Nador and the forests

3.5 Oujda and the Algerian borderzone

3.6 Algeria

3.7 Rif region

4 Shipwrecks and missing people

Introduction

At least for the international media, the last three months on the routes to Spain were remarkable for the large number of crossings around 18 May. In just a few days more than 10,000 people crossed the border into the enclaves of Ceuta and Melilla. We describe these events in more detail in part 1 of this report. Like all parts of the report, it is based on the constant work of Alarm Phone activists in the Western Mediterranean region and beyond. The report documents the continuing violence and repression against travellers and their ongoing resistance against it. The border crossings in May are no exception to those dynamics. People on the move are still instrumentalised in (political) power plays. Whatever the rhetoric deployed at the state level, the reality is that people on the move are deceived, detained, deported and denied access to proper housing. Self-organised infrastructures are destroyed (see for example parts 3.4 and 3.6).

Repression in Morocco is always high and even intensified after the May-crossings (see 3.2). This is why, with the exception of these few days in May, many people have abandoned the traditional jumping off points like Nador (see 3.3). Others, like the Rifean harraga, face interceptions at sea by the Marine Royale, the Moroccan Navy (see 3.7).

The Atlantic route to the Canary islands (see 3.1) remains the most frequented passage to Spain. This despite the continuous expansion of the repressive apparatuses in North-West African countries funded by European countries. The deadly outcome of these policies can be seen in the shocking numbers of dead and missing people (see part 4). In defiance of this politics, people keep on moving (see part 2) and protesting. We are enthusiastic supporters of their campaign to abolish Frontex (see part 3.5)

1 Promotion of migration – the crossings of May 2021

In mid-May, rumours spread like wildfire that the Moroccan Kingdom had told its border guards to stand down and there was a ‘window’ in the usually tight border control. Such a window is called a ‘promotion’ by sub-Saharan travellers. ‘Promotions’ have happened before and are part of the collective memory of the Moroccan-Spanish border. Amid escalating diplomatic tension between Spain and Morocco in the week of 17 May, up to 10.000 people, many of them minors, reached Ceuta either by swimming, taking to small boats or crossing the border fence. They arrived in the areas of Benzú and Tarajal or crossed the border fences, abetted by the absence (or inaction) of Moroccan forces. Some of the rumours of the promotion let people to believe that their papers would be sorted out in the enclaves so that they could go to the Spanish mainland. As this turned out to be false, some people tried to return voluntarily to Morocco whilst most people wished to continue their journey. Before 10 p.m. on 17 May, 300 people had already been returned to Morocco. Despite the unusually huge international media attention, the Moroccan government remained silent throughout the day.

In the days before 17 May travellers had already moved to Tangier as they had heard about the ‘promotion’. On 17 May, many of them came to the beaches around Tangier with small dinghys. Some tried to cross to peninsular Spain, but, due to the adverse weather conditions, the majority of people continued along the coast, heading for Ceuta.

By the 18 May, the Spanish authorities had deployed the army in support of the police. They deployed tanks on the beaches in an attempt to prevent people from crossing. They also forcibly implemented their policy of so-called ‘hot deportations’ at the border. As Moroccan security forces resumed preventing people from crossing the border, riots broke out on the Moroccan side of the border. They were answered with shots in the air and smoke bombs from the Guardia Civil. A video circulated on social media. It gives graphic evidence of police violence against minors and pushbacks from Ceuta to Morocco in the days from 17 to 19 May.

According to the local branch of the Moroccan Human Rights Association AMDH, the extraordinary border-crossing attempts at the Melilla border started on 18 May. Dozens of Moroccan harraga gathered in the neighbourhoods of Beni Ansar, Barrio Chino, Mariouari and Farkhana in order to attempt to jump the border fence to Melilla.

Our local contacts in Nador report that on that day, around 200-300 sub-Saharan travellers tried to reach Melilla via the border fence. Around 85 of them succeeded whilst the rest were blocked by the border guards. The following day, 15-40 (different numbers are being reported) sub-Saharan travellers were sent straight back to Morocco in a so-called ‘hot deportation’. This action was criticised by the AMDH, among others. The deportation happened in collaboration with the Moroccan forces in spite of the ‘promotion’ rumours.

On 21 May, there were also several other attempts to jump the fence, this time by young Moroccan and Syrian nationals, including at Mariouari and Barrio Chino. According to reports, some people reached Melilla, even though the Guardia Civil used tear gas on them. The exact number of successful crossings is not known. The news agency Deutsche Welle refers to 6 groups that attempted to jump the fence, with 30 individuals being successful. Later that day, 40 others managed to overcome the border fence. They were all Moroccan nationals.

The lack of border control by Moroccan authorities came after Spain allowed the Western Saharan leader of the Polisario Front, Brahim Ghali, to be treated for Covid-19 in Spain at the end of April. In a statement on May 8, Rabat said this was a “premeditated act” that would have repercussions. The Spanish government, however, later claimed it was not aware of Morocco relaxing its border controls. This example shows how Morocco uses its position at the EU’s external border to strong-arm the EU into accepting its occupation of Western Sahara. The conflict between Spain and Morocco has grown more acute since the former US president Trump recognized Moroccan sovereignty over Western Sahara at the end of 2020. This statement flies in the face of the UN recognition of the Western Sahara State. Morocco employs similar tactics, playing with migrant lives for diplomatic strategic reasons, as Turkey did in 2020. In addition, the Moroccan kingdom leverages the EU’s hatred of ‘foreigners’ to gain cover for its political and social repression and the widespread poverty in the country. As a consequence, many of its residents, Moroccans as well as sub-Saharan nationals, have no way out and Morocco can buy the silence and support of its European counterparts.

On 19 May, the Spanish and Moroccan governments reached an agreement to send adult Moroccans back to their country of origin in groups of 40 every two hours. By 22 May, 7,000 people had already been deported or ‘returned voluntarily’ from Ceuta. Additionally, police forces intensified their searches and interceptions especially around the Port of Ceuta, where many people were hiding in order to try to sneak onto ferries or jump into, onto or under trucks being shipped to Algeciras.

The Spanish Refugee Aid Commission (la Comisión Española de Ayuda al Refugiado, CEAR) condemned the widespread and well-established practice of sending people back without following the procedures established by law, i.e. proper checks on their identity or allowing people to lodge an asylum claim. These are grave violations of human rights.

Despite having paused the border control they usually enforce very violently, Morocco accepted Spain’s pushbacks. In return, on 18 May in the midst of the crisis, Spain promised Morocco another €30 million in financial aid in order to prevent migration to Spain. People struggling for a better future are taken hostage in the game of international relations.

Another effect of the mid-May mass crossings into the Spanish enclaves is that, in a plan announced on 16 June by Spanish Foreign Minister González Laya, Spain is now planning to fully include Ceuta and Melilla in the Schengen area. This will make a Schengen visa obligatory for all Moroccan nationals wishing to enter the enclaves. In consequence, inhabitants of the neighbouring Moroccan cities of Nador and Tetouan would require a Schengen visa in order to enter Ceuta or Melilla. If the plan is carried out, it would be disastrous for cross-border trade and would badly effect the local economy. Until October 2019, the external border of Ceuta was open to the neighbouring population for short visits. It was only closed in an attempt to halt the spread of Covid-19. The local population has held a number of demonstrations in Fnideq calling for a reopening of the border, emphasising the economic hardship a closure causes.

2 Sea crossings and statistics

From late March to June, Alarm Phone was contacted in a total of 66 cases involving approximately 1,443 people in distress at sea. This is more cases than Alarm Phone dealt with in the winter of 2020 (60 cases) or in the first three months of 2021 (31 cases).

Of these 66 cases, 40 boats carrying 801 people arrived in Spain. The UN reports approx. 7,000 new arrivals in Spain during April, May and June. These numbers show that Alarm Phone assisted around one in nine people who crossed over to Spain. This is an increase on previous years and could show the network’s growing presence in the region.

Of the boats that didn’t make it to Spain, 18 returned to Morocco, 9 of which were intercepted and pushed back to Morocco, 8 were rescued in distress and one returned autonomously. Four boats carrying a total of 205 people were reported missing, and the outcome for two cases was unclear. Despite the rescue efforts of merchant vessels, fishing boats and coast guards, 60 people died during rescue missions. Our thoughts and rage go out to those whose lives lost at sea as the struggle for free movement continues.

However, it remains true that many cases go unreported. People arrive in Spain or are left missing at sea without any organisation being informed. There is simply no way of knowing whether our figures depict the true reality of crossings in the Western Mediterranean and the Atlantic.

3 News from the regions

3.1 Atlantic Route

Boat journeys and Alarm Phone cases

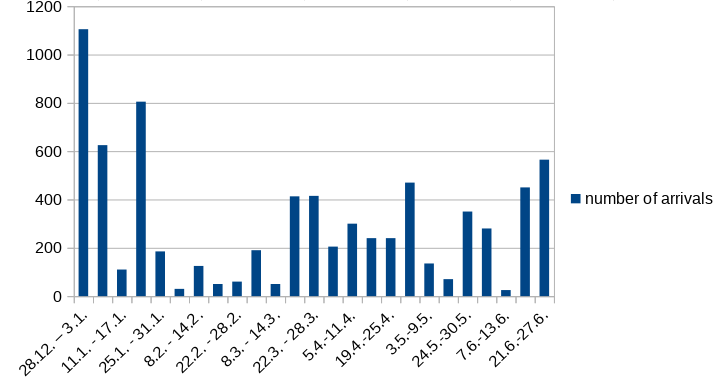

The Atlantic route continues to be the most frequently travelled route to Spain. It accounted for half of all arrivals to Spain in the first six months of 2021, namely 6855 out of 13176 arrivals (data as of 27 June 2021). This is already significantly more than in the same time period in 2020. As the following chart of arrivals per week shows, crossings have increased in the second quarter of the year, with several peaks. For example, seven boats carrying 263 people arrived on the Canaries on 30 April, and another seven boats with 298 people reached the Canaries between 26 and 27 June.

Source: own compilation, data by the UNHCR Spain

In general, the number of women travelling this route has declined. They now account for about 15% of travellers. On the other hand, the number of Moroccan travellers has increased. They now constitute a quarter of all arrivals. In general, we can see an increase in the range of the countries of origin for those attempting the route. While most travellers are still from the immediate region, countries like Senegal, Gambia, Guinea-Bissau and Mahgreb states, there are now many arrivals from further away like Ivory Coast or even the DRC. In late May, there were even travellers from Yemen and Iraq among the arrivals.

The route remains as deadly as ever. Official estimates suggest that people are dying or going missing at a rate of roughly one death per day. If this is correct, it would mean that around 180 people have died this year. We believe this number to be much higher. Through their meticulous work and constant contact to relatives, the collective Caminando Fronteras has established that 57 boats were lost in the past six months on the Canary route alone, resulting in a horrific number of 1922 dead and missing.

At Alarm Phone, we were alerted to several boats that went missing, at least some of which cannot have been included in the official statistics. AP127 was a boat carrying 50 people. They departed from near Laayoune at the end of March and went missing. We have no information on several boats that left in late May and early June: AP271 (32 people from Laayoune), AP300 (52 people from Laayoune), AP307 (62 people from Laayoune) and AP308 (36 people from Dakhla). We very much hope that all of these 232 travellers arrived somewhere safely and do not share the fate of the boat that was found in the Carribean in mid-May. It had drifted for 4500 km, all of its passengers dead.

Alarm Phone shifts were also involved in some of the horrible shipwrecks that occurred on the Canary route in the last few months. In late May, AP301 resulted in a shipwreck off the shores of Western Sahara. The Marine Royale, the Moroccan Navy, only managed to rescue 30 survivors. 15 other travellers died during the badly conducted rescue operation. Our source here is Alarm Phone member A., from Laayoune, who talked to the survivors.

The recent shipwreck off the northern shores of Lanzarote (Órzola) with several dead was also accompanied by Alarm Phone. The same applies to the horrible shipwreck just some days ago (AP359), with 40 dead and only 22 survivors. The survivors were picked up by a fishing boat.

Another tragedy happened in late April, when three survivors where found, completely by chance, nearly 500 km south of El Hierro, the southwestern island of the Canary archipelago. On board, there were 24 dead. Family members think that the boat orginally left with 57 people on 5 April from Mauritania. Apart from the 24 bodies found on the boat, it adds another 30 lost lives to our sad count.

Sheer luck has also resulted in the rescue of several other boats. A few boats were spotted by merchant vessels, sometimes hundreds of kilometers away from the islands, and the passengers brought to safety. A British merchant vessel rescued 25 people more than 400 km south of Gran Canaria (AP296) on 8 June. Another cargo ship spotted one dead and 35 survivors nearly 500 km south of Gran Canaria. One passenger, a young girl, died shortly after the rescue. Another boat, 65 km off the coast of Western Sahara, was spotted by a merchant vessel on 1 June. It is particularly worrisome that this was a rubber dinghy. Travellers who embark on this route usually do so in a more sturdy, wooden boat.

Another big shipwreck never really made it into the European media. In the first week of June, a boat that had left Senegal with 150 travellers was picked up by the Marine Royale. There were only 79 survivors. They were all subsequently deported to Senegal.

Besides witnessing these dangerous and deadly journeys, we have also seen the ramping up of repression. Since arrivals to the Canaries shot up last autumn, politicians have been trying to curb departures. We all know that huge sums of money are made available to “stop illegal immigration” (for example, Spain alone has given €90 million to Morocco in the past three years). This applies not only at the European and Spanish levels. Some weeks ago, Germany pledged €5 million to “reinforce” maritime border control in Mauritania. In Mauritania, the levels of repression are extremely high, as Alarm Phone member F. reports from the ground:

“The situation is too complicated here in Mauritania. Because here you risk going to prison, you risk being deported. The organizers of the journeys end up directly in prison and can get a prison sentence of two to five years. The travellers are deported back to their country of origin. It’s more complicated than in Morocco, since there, you don’t risk being deported to your country of origin.”

For example, 25 travellers were arrested on 27 April near Nouhadhibou and, after some time in custody, deported to their countries of origin.

However, prison sentences are also being dished out on the Canary Islands, especially when passenger deaths have caused media attention. For example, just in June, the ‘captain of a boat’ was sentenced to eight years in prison for the death of a baby on board. There were also several other homicide charges levelled against supposed ‘captains’. While we, Alarm Phone, of course condemn any travel agent who prepares the journey badly or exploits and neglects the customers for their own profit, we maintain that the mass dying at the EU border is not the fault of some individuals (or the so-called “smugglers”) who can be locked up in prison. It is the European Union that creates the basis for human trafficking through its deadly border regime and should therefore be charged for mass homicide – borders kill!

We stand in solidarity with every single traveller who challenges this lethal system of border controls and express our gratitude to all those who decry this inhuman system and shout out loud “Abolish Frontex” – like our comrades did on the Canaries, in Oujda (Morocco), see part 3.5, and many other places across Europe and Africa.

Situation on the Canary Islands

One of the biggest problems in the past months was the ban on onwards travel to the mainland for those who came to the Canaries by irregular means. In mid-April, two judicial reviews in Las Palmas questioned the legality of preventing people from leaving the archipelago. According to the reviews, valid passports and asylum seeker documents must be recognised as sufficient to fly. Thus, there are two ways of travelling to the mainland now, either by NGO or government transfer or by self-organised journey via plane. The latter requires relatives on the mainland or a support network who can pay for the journey. Since April, the government has accelerated transfers to the mainland so that the biggest camp, Las Raices on Tenerifa, has emptied to half its size. In early April, riots broke out after fights over the very restricted space and resources. The catastrophic situation that prevailed in the camps until April has also recently been studied and criticized by the NGO Médicins du Monde. The reduced number of inhabitants has also freed resources to speed up the registration procedures. New arrivals are now registered, their fingerprints are taken, they are then tested for Covid-19, isolated and transferred to the camps within four days, instead of the weeks of forced confinement people were made to endure for most of the last 18 months. However, thousands of people are still stuck on the Canary Islands. If arrival numbers continue growing, as they did in the last few weeks, the situation will get chaotic again soon enough.

The fraught relations between Morocco and Spain have had a positive effect though. In April, deportation flights to Morocco/Western Sahara from the Canaries were suspended. Up until then, it had actually been much more difficult for Moroccan travellers to stay, since they, contrary to the experience of many of their sub-Saharan fellow travellers, were often denied access to proper legal advice or the asylum procedure and were deported quickly.

Situation in Western Sahara & Morocco

When people are detained by Morocco, they still have to spend an arbitrary amount of time in custody and end up being forcefully deplaced afterwards. They often spend days in crowded and ill-equipped detention centres without access to enough food, water, blankets, hygiene facilities and more. Even during the month of Ramadan these discriminatory practices did not stop. This is well documented in videos taken by a group detained on 7 May near Laayoune:

Photo from inside a detention centre near Laayoune, with people huddling in the shade of a courtyard, in lack of proper rooms and beds. Source: AP Maroc

Housing conditions are abysmal in Laayoune and other areas where many people wait for their departure. Due to the arrival of many travellers from the North in Western Sahara, people have very little space at their disposal. This is then used as an excuse by the police when they carry out their raids, a rather cynical argument as Alarm Phone member A. from Laayoune points out:

“The authorities use the argument that there are too many people in the apartments as a justification (for the raids), but actually, there are so many because the authorities threaten landlords into not giving migrants any apartments to rent.”

This overcrowding of living space also has a deleterious effect on people’s health. Tuberculosis is rampant in many living quarters since there is no adequate ventilation. In addition, much of the housing stock inhabited by potential travellers is old and in very bad condition.

3.2 Tangier and the Strait of Gibraltar

General situation

Our local contacts report that the situation for people on the move in Tangier and surroundings remains precarious. This is because of police checks, arrests and constant surveillance, especially in the city areas of Bukhalef, Misnana and Braness, where most of travellers from the sub-Saharan communities live. Removals to the South are still a common practice (e.g. to Tiznit, Marrakesh, Casablanca, Agadir) and happen on a daily basis.

This situation has led to widespread abandonment of this route by people on the move. Most people have chosen to go back to other cities (e.g. Rabat and Casablanca) in order to escape the constant police controls. In recent times, the city of Tangier even installed a form of checkpoint on the roads into the city. At these barriers, the police carry out inspections to prevent people who take direct action for their freedom to move from entering the city and to facilitate their pushback to the cities of their departure.

Crossings

In May, Tangier and its environs saw the effects of the rumours that Morocco had dropped its border controls (see part 1). These rumours created a mass movement of travellers to Tangier. People came from all around Morocco mainly in the hope of crossing to Ceuta, though this was not the only destination. Our local contacts in Tangier report that, in this brief period, many groups of sub-Saharan people ran to the beaches and jumped onto rubber boats heading for Tarifa. Videos circulated within the communities showing several groups of four to six people, each group with a boat which they dragged along the dunes of the beaches of Tangier, shouting “Tangier is open”. It did not last long. Within a few days, Morocco took back control of the borders. This exceptional situation did however disrupt the regular traffic and resulted in an increase in police checks, police raids and forced removals to the South.

Apart from this exceptional situation in May, crossings from the region of Tangier to Spain remain rare. In general, people are unable to cross from Tangier. “Bozas” (“Victory”, the word for successful arrivals in Bambara) are quite infrequent because of the tight security enforced by Moroccan authorities in the city of Tangier, in the forests nearby where people used to stay, and along the shores from which people attempt to start their journey. The targeting of clandestine networks is rigorous and, especially since 2018, high on the agenda of national and regional officials. According to AP activists, successful crossings are more and more likely to be small and self-organized initiatives, whereas in the past it was big trafficking organisations who managed crossing attempts from Tangier.

Alarm Phone Cases from Tangier

The Alarm Phone dealt with six cases around Tangier in the period from April to July.

On 16 May, we were alerted by a boat of eleven people, including two women starting from Ashakar. We informed the authorities, but they were returned by the Moroccan Navy almost ten hours after we had forwarded their exact position to the authorities – 10 hours during which they could have drowned.

One day later, the Alarm Phone was alerted by four boats leaving from Tangier. Three people in a kayak left Tangier and alerted the Alarm Phone because of very strong currents. After informing Salvamento Marítimo, we learned that they were rescued near Tarifa and brought to Algeciras.

On the same day, five people, including one women, left from Tangier. The situation became dangerous because of the weather conditions, but luckily they managed to return to Morocco on their own and arrived safely.

The third boat of 17 May had an unknown number of people on board. We were alerted by relatives of people on the boat because they were adrift between Tangier and Tarifa. Later on, we were informed by relatives that they had been rescued to Spain and taken into custody.

The last boat in distress that day had four people on board. It was returned to Morocco by the Marine Royale.

On 18 May, our hotline was informed about a boat with seven people in distress that had launched from Tangier. In the end, they were brought back to Morocco.

Within the communities, there is hope that the conflicts between Morocco and Spain over the Western Sahara will continue and lead to another crisis, because then the summer could offer the long hoped for possibility of finally being able to leave Morocco.

3.3 The Enclaves: Ceuta and Melilla

Because of the entry of more than 10,000 people into the enclaves in mid-May, the Spanish Ministry for Home Affairs is delaying the publication of the numbers of irregular entries in the first part of 2021. However, as we previously reported, sea crossings, especially into Ceuta, have increased since the beginning of the year. This trend continued throughout April. Many individuals or small groups tried to swim into Ceuta or to circumvent the border fences at Tarajal and Benzú with kayaks, surf boards, or with dinghies. On 25 April, about 159 travellers simultaneously attempted to swim into the enclave. The Moroccan authorities barely did anything to save people in distress. At least two people died in the attempt. The following day, another large group faced heavy repression on the Moroccan side in a similar attempt. Despite the reconstruction (and reinforcement) of the fence at Tarajal beach and the reinforcement of border controls, small groups continue to successfully cross the border.

During the unprecedented border crossings into the enclaves, Alarm Phone received several distress calls. Because so many people are now trapped in Ceuta and Melilla, even more travellers are trying to cross to the peninsula from the enclaves. These attempts happen on a daily basis and by different means. On 28 May, Alarm Phone was alerted by the brother of a man who had tried to swim from a village close to Ceuta to Gibraltar. Against all odds, the family later told AP that he woke up from a coma in a hospital in peninsular Spain and is now somewhere in a camp.

Despite the rulings by the Supreme Court, according to which the direct expulsion of irregular entrants is legal only upon proof of a criminal record, and by the Administrative Chamber of the High Court of Justice which confirmed the right to free movement throughout the country for asylum seekers in both Ceuta and Melilla, the practice of deportation continue.

On 27 and 28 April, groups of young Moroccans who had swum into Ceuta were deported to Morocco despite the border still being closed. This practice continued after the crossings on 17, 18 and 19 May, as the Moroccan government allowed the repatriation of 30 Moroccan nationals per day. It is especially cynical given that these deportations are taking place as hundreds of Moroccans are trapped in Ceuta by the ongoing closure of the border and are forced to cross it, if at all, by irregular routes. 40 people from Yemen were also expelled from Ceuta. The AMDH Nador condemned this unlawful deportation.

In Melilla, 700 Tunisians are facing deportation, or are pushed towards “voluntary” return by their ongoing, soul-crushing internment in the CETI (Centro de Estancia Temporal de Inmigrantes, ‘temporary’ holding centre for irregular arrivals) of Melilla. As we have previously reported, they have been held since the end of 2019 despite protests and hunger strike.

The situation in the already overcrowded, unsafe and unhygienic CETIs and centres for unaccompanied minors deteriorated after the large number of crossings in May. The infrastructure is now completely overstretched. NGOs published a report condemning the numerous issues and ongoing human rights violations, especially the ones minors are forced to endure in Ceuta. But instead of building new structures, the government destroys self-made shelters and shuts down possible alternatives, for example by the eviction of the Plaza de Toros in Melilla. Spanish and European money is directed to securitisation and control rather than meeting the basic needs of those living on the streets. 5 million euros will be provided by the Spanish state over the next two years for the surveillance of home-shelters for minors in Ceuta. Such surveillance has been outsourced to private security companies since 2019. From 16 June on, Frontex has recommenced support for Spanish border forces. The collaboration has been dubbed ‘Operation Minerva 2021’ and will continue throughout the summer months.

3.4 Nador and the forests

Our local contacts report that many sub-Saharan travellers have left the Nador region for Dakhla or Laayoune to try to cross to the Canary Islands. The sea passage from Nador towards mainland Spain remains blocked for several reasons, including the ongoing lockdown and the high price of a seat in a boat. The Alarm Phone dealt with six cases from the Nador region in the period covered by this report. Three boats were eventually rescued to Spain, two boats were intercepted by the Moroccan Marine Royale and, on 1 June, one boat, carrying 13 passengers, was rescued by fishers and brought back to Morocco.

An unprecedentedly high number of crossing attempts happened in mid-May at the border fence with Melilla (see chapter 1). But apart from this extraordinary ‘window’, this border zone was tightly secured. In a statement released on May 24, the AMDH Nador describes an unprecedented mobilisation of Spanish and Moroccan forces on both sides of the border, including units of the Spanish army, helicopters, Guardia Civil and police from the Spanish side, and large numbers of police, gendarmerie and auxiliary forces from the Moroccan side.

For the travellers who still remain in the Nador region, among them many women and children, the situation is difficult in all of the encampments in the forest. Our contacts report that even during the month of Ramadan there were frequent raids. Practically on a daily basis, the authorities destroy and burn down the travellers’ makeshift camps. The violence leaves many injured. The following picture is from an attack in Bouyafar, documented by the Moroccan Human Rights Association, AMDH – Nador branch:

Source: AMDH Nador

As the local Alarm Phone group reports, almost none of the travellers in the region have a source of income for food and shelter, and the prolongation of the lockdown risks starving thousands of people who in normal times would be dependent on social aid in the cities of Nador, Berkane, Oujda and the surrounding area. Many among the sub-Saharan communities, regularised or not, are in distress and already undernourished with only one meal every two days. In the region of Nador and Berkane alone, it is estimated that there are more than 4,000 people who no longer have access to food aid.

Hermann Mbatch, AP Berkane member and founding member and former president of the association Aides aux Migrants en Situation Vulnérable (AMSV), estimates that, just in early June, there were up to 200 new arrivals, mainly from the forests, in the city of Berkane. He tells us that only those with a social network of family or Moroccan friends are able to meet their basic needs. The most vulnerable were getting by, for the most part, with the help of associations or by begging on the city’s roundabouts. As they can no longer move freely because of the lockdown, their situation has become critical. In Berkane, the local association Homme et Environnement already sounded the alarm in a communiqué issued in June. They predicted an imminent humanitarian catastrophe for the most vulnerable travellers in Berkane.

Sub-Saharan travellers are threatened not only by police violence in and around Nador, but also by groups of ‘clochards’, thugs who from time to time attack sub-Saharans and steal their belongings. These attacks take place with the tacit permission of the police. On 29 April, as AMDH Nador reports, a man was seriously injured by such a group in Lakhmis Akdim. The victim had to be hospitalised. The AMDH Nador demanded that the commander of the Gendarmerie prosecute this and other attacks. These attacks, though, are part of a well-known and widespread practice that has been going on for years without the authorities ever showing any interest in providing protection to sub-Saharan travellers, so there is little hope that the authorities will respond to the demand.

On the contrary, sub-Saharan travellers as well as Yemeni and Syrian nationals and Moroccan minors still face arbitrary arrest on the streets of Nador city and then removal to the interior of Morocco.

On 20 May, the AMDH reported that 28 young Moroccan nationals had been arrested at Farkhana and Barrio Chino/Nador after throwing stones. According to AMDH’s lawyer, they will be judged in court, but it is still not clear what charges they will face.

We are aware that Moroccan nationals continue to organise border crossings from Nador. The region suffers from economic hardship, and many young people are unemployed and their future prospects look bleak. As our contacts are more aware of the situation for sub-Saharan travellers, our reports from the region mainly cover sub-Saharan migration attempts. We will try to report more exhaustively from harraga movements in the upcoming reports.

3.5 Oujda and the Algerian borderzone

In the Oujda region and the border area between Morocco and Algeria, the situation for travellers is still extremely precarious. Furthermore, Covid-19-related state aid is only available to people with Moroccan passports, whilst people who ask for money on the street are subject to police repression.

The Alarm Phone team in Oujda reports a deportation from Nador on 6 April. 15 people were pushed back to the border area. The deportees arrived in Oujda the next day and two minors reported what had happened.

There was a tragedy off the coast of Oran on the night of 18-19 February. 13 people died and two survived when the boat that they were travelling in capsized. AP Oujda stayed in close contact with the families. The boat carried travellers from Morocco and Algeria. They capsized off Oran, and the bodies washed up on both sides of the closed border. After negotiations with the competent governmental authorities about the return of the bodies to their relatives, the airlines Royal Air Maroc and Air Algerie offered repatriation from Oran, via Casablanca, to Oujda for the sum of €4,900 per body. This price is completely unaffordable for families on an average income. Considering the fact that the two cities are not even 300 km away from each other, it is outrageous and absurd. After political pressure, the land border was actually opened on 14 April to allow the return of a corpse to his family in Oujda. What will happen to the other dead is not yet clear. Three people are still missing. AP Oujda will continue to support the relatives.

AP Oujda, along with other activist groups in the region, work non-stop to support people on the move and challenge the lethal border regime that confronts people when they travel through the Sahel and North Africa.

Abolish Frontex action in Oujda 09.06.2021. Source: AP Oujda

People in Oujda also joined the transnational campaign to “Abolish Frontex“. There was an action on 9 June to draw attention to the inhuman policy of the European Agency for Border Security and to demand its abolition.

3.6 Algeria

Despite criminalisation and deaths, Algerians keep moving

Although in the first months of 2021, Algerian citizens were the second largest group by nationality among Mediterranean arrivals in the EU (after Tunisia), by 31 May 2021 Algeria had dropped off the list of the 10 most common nationalities reaching the EU via the sea. Nevertheless, looking at the numbers of arrivals to Spain, Algerian travellers are the largest group by nationality (ahead of Tunisians).

As a matter of fact, “El Corredor” (the name given to the Mediterranean corridor between Western Algeria and the Iberian Peninsula) remains the second most frequented sea route to the EU by the harraga, after the crossing to the Canary Islands. However, travellers are constrained by significant criminalisation (they risk two to six months in prison and a fine of 20,000 DA for “illegal exit from the territory” and interception operations are regularly conducted by the Algerian authorities.

In April, several tragedies occurred. They were reported by the Algerian media. On 4 April, the corpse of the young Raï singer Souhil Sghir was found near Terga beach, close to Oran.

On 5 April, two women and their daughters drowned while attempting the crossing.

We know that these tragedies are only a few out of too many others, and we are always deeply moved and angry to learn about the loss of these lives. Our hearts and thoughts are with the deceased and their families. As a small homage to his memory, here is a video of Souhil Sghir singing:

Many travellers made it to Spanish or Italian shores, and we wish them a warm welcome. Nearly 10,000 Algerian citizens reached Spain and Italy between January and April 2021. In early May, more than 30 boats carrying travellers from Algeria were rescued by Salvamento Marítimo Almeria.

Alarm Phone Cases

Alarm Phone was involved in three cases where boats left Algeria. Two of them (3 April and 26 June) were cases of boats taking the central Mediterranean route towards Italy. In the Western Mediterranean, Alarm Phone dealt with one boat on 7 May carrying at least three Syrian people. The boat reached Spain safely.

In addition, the AP shift teams still receive calls from the sisters, brothers or other relatives searching for news of their loved ones who have tried their luck on “El Corredor”.

Systematic abuses against sub-Saharan communities and mass deportations: Voices raised

Since the beginning of the year, more than 4,000 people have been taken by the Algerian police to the border with Niger, which is in the middle of the desert, to a place called “point zero“. The deportation process is generally the same. First you are arrested, although you may well have been in Algeria for several years; then you are sent to detention centre for a few days or weeks; and finally you, along with other detainees, are packed into buses and taken to the desert. Abandoned there, you risk getting lost. Many people are never found and die in the vast expanse of the Sahara. As a recent example, Alarm Phone Sahara reports that on 10 May 1,218 people were pushed back to the border area between Algeria and Niger. The group included 61 unaccompanied children, many of whom showed signs of abuse.

On April 21, the French NGO Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) released a report. They concluded that “these policies, implemented to stem the flow of migrants, have not prevented them from seeking a safe place or a better life. On the contrary, it has only led to more criminalisation and violence against migrants.”

Alarm Phone Sahara, the sister project of Alarm Phone active in the Sahel-Saharan zone, Pateras de Vida (Larache, Morocco), Alarm Phone Morocco, Afrique-Europe-Interact and eight other organisations from Mali, Morocco, Germany, Togo, Italia, Algeria and Tunisia signed a joint statement on 25 April to condemn these repeated human rights violations.

“The situation is so alarming and critical that we, as defenders of human rights in general and the rights of migrants in particular, are called upon (…) to raise public awareness at the regional and international level of the various abuses and multiple violations committed against migrants, as well as to take positions in defending and protecting the rights and freedoms of migrants.” (Source: AP Sahara)

In response to years of testimonies and reports by NGOs of violence and torture in April Algeria announced that they would be opening a so-called reception center in Djanet (Bordj El Haouès, on the border with Niger and Libya). It would appear that the Algerian state has learnt from its EU counterparts. They now wish to tighten security and hide the systematic abuse behind the facade of bureaucratic processes and bland, quasi-humanitarian language.

The Algerian state has also been spurred to take this move because of the enormous cost of its disastrous migration management. The former president of the National Council of Human Rights (Conseil national des droits de l’homme, CNDH) of Algeria declared that “between 2014 and 2016, Algeria spent 800 million dinars [€5 million] to repatriate 18,000 women and 6,000 sub-Saharan children.” In a report published on May 31, the Nigerien CNDH made it clear that between 500 and 600 migrants are pushed back every week from Algeria to Niger.

Alarm Phone Sahara together with the transnational network Afrique Europe Interact organised, on 21 May, a transnational day of action “Freedom of Movement, No Expulsions!” in Kindia (Guinea), Bamako (Mali), Agadez (Niger), Sokodé (Togo), Mbanza Ngungu (Congo DRC) and Berlin (Germany). Activists protested against the deportations of nationals of sub-Saharan African countries from Algeria to Niger, but also against the imposition of European border controls in Africa and against deportations from European to African countries. See the video of the final declaration here:

3.7 Rif region

The current situation in the Rif region is much the same as at the beginning of the year. As the Moroccan regime’s repression continues, young Rifians organise among themselves to make the crossing to the south of Spain.

In the last three months though, control at sea has increased. The number of interceptions carried out by the Marine Royale has increased. This increase in control has caused a decrease in the number of dinghies leaving from the Rif region. Nevertheless, according to our investigations, the number of arrivals in this period is similar to that in the first 3 months of the year. We counted 179 people who made it to the Spanish peninsula from the Rif in April, 151 in May and 93 in June. We would guess that 400-500 people made the journey successfully.

As regards Alarm Phone, between 1 April and 1 June the network was involved in 17 cases. They were all boats that left from Al Hoceima to go to Spain. The 17 cases are recorded as involving approx. 180 people. According to Alarm Phone data, most of these people were men and of Moroccan nationality. Three of these boats were intercepted by the Marine Royale, and the fate of the people in one of the cases is still unknown. The rest, however, were rescued by Salvamento Marítimo to Almería and Málaga. Here are two examples of these cases:

- On 6 April, Alarm Phone is alerted to a boat of 20 people which had left Al Hoceima and got into trouble. On 7 April they are rescued by Salvamento Marítimo and taken to Motril.

- On 9 June, Alarm Phone is alerted to 28 people on a rubber boat in distress at sea. The boat has left from Al Hoceima. Salvamento Marítimo were already informed; however, on 10 June, it is confirmed that they have been intercepted by the Marine Royale and taken to Morocco.

4 Shipwrecks and missing people

In the last three months, we counted more than 150 deaths and several hundred disappearances in the Western Mediterranean region. Despite all of the efforts to document the dead and missing, we can be sure that the real number of humans who have died at sea in the attempt to reach the EU is much higher. We want to remember each one and commemorate each unknown victim in order to overcome the political system that killed them.

On 1 April 2021, a dead body is found on the beach of Vera, in the province of Almería, after a shipwreck in Mazzarón.

On 3 April, the dead body of a young, unidentified man is found on the beach of Orales, Oran, Algeria, believed to be a harraga.

On 3 April, the body of a young man who drowned is recovered off the beach of Bider, Algeria.

On 4 April, the parents of the young singer known as Souhil Sghir identify the body of their son. It was found on the beach of Terga, Algeria. More info: [1]

On 4 April, a 60-year old who probably tried to swim towards Spain or Morocco is found dead on the beach of Benzú, Ceuta. More info: [1], [2], [3]

On 5 April, the lifeless body of a woman is recovered by the fishing boat La Mairena off the coast of Fuerteventura, Canary Islands, Spain.

On 7 April, a body is found on the beach of Melilla next to the Rio de Oro. The corpse is that of a young man who was served with an expulsion order when he turned 18. He drowned on his last attempt to reach the mainland hidden on a ferry. More info: [1], [2]

On 7 April, a dead body, identified as that of a woman of sub-Saharan origin, is found floating in the sea some 37 kilometres off the coast of Fuerteventura. There is no record of any shipwreck, but on 24 March a boat was lost and not found.

On 11 April, a boat is rescued 220 km south of El Hierro, Canary Islands, Spain. It departed from Nouakchott, Mauritania. On board are at least four dead people. Several others have to be hospitalized. More info: [1], [2], [3], [4]

On 11 April, the dead body of a person of sub-Saharan origin is found eight miles off the harbour of Al Hoceima, Morocco.

On 13 April, three young travellers, Souliman, Achraf and Ayoub, leave Tangier early in the morning on board a kayak. Later the body of Souliman will be found dead on Tres Piedras beach in Castillejos. The other two young men are still missing.

On 13 April, a boat capsizes off Porto Rico beach, South of Dakhla, Western Sahara. 15 people survive but one person dies.

On 14 April, the dead body of a young man of sub-Saharan origin is found floating in the vicinity of Aguadú, Melilla.

On 14 April, a dead body is found on the beach of Tarajal, Ceuta. It’s assumed that the death of the young man, who was of Moroccan origin and about 20 or 25 years old, was caused by drowning.

On 20 April, a shipwreck is recorded off the coast of Mostaganem, Algeria. Only three people survive, four people die, and five are still missing.

On 24 April, the remains of a young man, later identified as Suleiman al-Halimi, are washed ashore on the beach of Fnideq, Morocco. More info: [1], [2], [3]

On 24 April, three swimmers reach the beach of Tarajal, but one corpse has already been washed ashore. The body is that of a young man who, despite his bouyancy aid, appears to have died in attempting to swim from Castillejos to Ceuta.

On 25 April, two dead bodies are recovered off the coast of Fnideq, Morocco. The dead are identified as Murad Al-Sakhwani and Youssef Al-Abbas. They were between eleven and 14 years old. According to the media, in a two-day window around this date, 70 other people managed to swim into the enclave of Ceuta. More info: [1], [2], [3]

On 26 April, 24 dead bodies are recovered from a boat that had left Nouakchott three weeks before. It was found by chance 500 kilometres off El Hierro. Of the 59 occupants, only three survive, 32 remain missing. More info: [1], [2], [3], [4], [5]

On 29 April, one person dies and 20 people survive after a rubber dinghy burst off the coast of Achakkar, Tangier, Morocco.

On 30 April, a boat which left Agadir and has been at sea for three days is intercepted near the coast of Lanzarote. Three people survive but 12 others are reported missing.

On 2 May, a dead body is found on the beach in the region Ben Azzouz, Algeria. It is assumed that it is a harraga.

On 4 May, there is a search for two boats with more than 80 sub-Saharan Africans between them. The boats were bound for the Canary Islands.

On 12 May, no trace is found of two boats with 61 people between them.

On 15 May, the remains of a man from south of the Sahara are washed ashore at Tangier, Morocco. It is likely that he drowned after the boat he was in capsized.

On 17 May, the lifeless body of a minor is found on the beach of Tarajal, Spain. The young person tried to swim into Ceuta.

On 19 May, an unidentified body, believed to be that of a Moroccan harraga, is found near Habibas Island, Algeria.

On 19 May, three dead bodies are found on a beach close to El Jadida, Morocco. 17 people are still missing. More info: [1], [2], [3]

On 20 May, adding to the minor who died on May 17, another body of a minor is found at Tarajal beach. Both have been buried at Sidi Embarek cemetery.

On 20 May, a boat with 32-34 people which departed from Dakhla is declared missing after a search and rescue operation to the south of Gran Canaria proves fruitless.

On 21 May, another boat with 32 people which left from Laayoune goes missing (Source: Alarm Phone).

On 22 May, a young man dies after he falls from a height of 10 metres while trying to access the harbour of Ceuta. Two more dead bodies are found. The victims appear to have drowned. More info: [1], [2], [3]

On 29 May, a boat capsizes and people fall into the water during an interception operation by the Moroccan Navy. Ten people are rescued but one person is left in the middle of the ocean.

On 31 May, at least 495 people are given up as missing. They were passengers on ten or so boats that had left Senegal, Western Sahara and Morocco in the preceeding 10 days.

On 2 June, a boat with 62 people on board goes missing. It had left Laayoune (Source: Alarm Phone).

On 3 June, 30 people are rescued to Morocco and 15 people die during a rescue operation by the Moroccan Navy. According to survivors, the rescue was a disaster and people went overboard and drowned.

On 4 June, a Mauritanian boat with 14 dead bodies arrives on the island of Tobago in the Caribbean.

On 9 June, one person dies after falling into the sea from a dinghy south of Fuerteventura.

On 15 June, one dead body is found off the coast of Ceuta. The young man was wearing a wetsuit, from which it is inferred that he was trying to reach the coast of Ceuta by swimming.

On 17 June, at least four people die, including a pregnant woman and a child, after a dinghy is shipwrecked off the coast of Órzola, Lanzarote, Spain. The boat departed from Tan-Tan, Morocco. 41 people survive, but at least three people are missing. More info: [1], [2], [3], [4]

On 20 June, a search and rescue operation is carried out south of Gran Canaria, but a boat with between 32 and 34 people on board cannot be found.

On 20 June, one person goes missing after falling into the sea. 42 people travelling on a dinghy are rescued near Fuerteventura.

On 24 June, one dead person is found among a group of 23 sub-Saharan men rescued by Salvamento Marítimo south of Gran Canaria.

On 27 June, one person dies after falling into the water during an interception operation carried out by the Moroccan Navy. Another person left floating in the sea south of Gran Canaria is rescued later by Salvamento Marítimo.

On 27 June, a boat with around 60 people, including 15 women and two children, capsizes off the coast of Western Sahara. 40 people die. Among the dead are 10 women and two children. A fishing boat rescues twenty-two survivors.

On 28 June, two dead bodies are found in a boat off the coast of Gran Canaria. 33 people survive, seven men are hospitalised. One day later Alarm Phone is informed that a third person was unable to overcome the critical condition in which he arrived after being adrift in a boat for several days and died in the hospital of Gran Canaria.

On 29 June, a boat goes missing along the Canary route. Alarm Phone had been alerted to the boat, which left Dakhla on 25 June with 46 people on board, including 22 women, one of them pregnant, and five children.

On 29 June, one man is found dead after a boat is spotted by a merchant vessel. The boat had been at sea for 17 days at sea. 35 people (six children, 16 women and 13 men) were rescued by the merchant vessel. A helicopter of SM took three people from the merchant vessel, a woman and a man who are taken to the hospital in critical condition, and a little girl who dies during the flight.