“After the men, it’s the women and children who get lost on the new migration routes. Among others, they nourish the Mediterranean and the Atlantic”

Artist Ndööndy AW

The period covered in this Alarm Phone Western Med Regional Analysis is, of course, an exceptional period due to the impact of Covid-19 in the transit country, Morocco. Crossing attempts came close to an halt on most Western Mediterranean routes. Only the passage to the Canary islands remained somewhat open. Apart from keeping the distress hotline running and accompanying 7 boats on their perilous journeys across the western sea routes, the Alarm Phone attempted to support its members as well as the communities of people in transit; an act of solidarity with those whose already precarious position was further undermined during these hard times of lockdown in the Kingdom of Morocco.

Content

1 Covid-19 in the Western Mediterranean

2 Sea crossings and AP experiences

3 News from the regions

3.1 Tangier and the Strait of Gibraltar

3.2 Nador and the forests

3.3 The Western Saharan route

3.4 Oujda

3.5 The enclaves: Ceuta and Melilla

4 Shipwrecks and missing people

1 Covid-19 in the Western Mediterranean

Like everywhere else, life has been dominated for three months by the crisis caused by the spread of the Covid-19 virus. And like everywhere else, in Morocco those who have to live in the most precarious circumstances are hit the hardest. This group includes the travellers who are trying to enter the EU via Morocco. People in transit are among the people most exposed to the risk of Covid-19 infection. But, above all, they are the most vulnerable to the socio-economic consequences of the health emergency. Public life is almost paralyzed, as Morocco has introduced one of the strictest set of regulations in response to the crisis. Only the most necessary shopping facilities are open, the public transport system is almost completely suspended. In addition, there is a curfew. You must carry an official permit to be allowed to move on the streets. You can apply for such a permit only in your own residential district. In each household only one person is allowed to apply for a permit. The other members of the household are not allowed to move more than 150m away from their place of residence. These regulations are strictly enforced by the police. In addition, those who have to go to their place of work or to the doctor need a permit to go and after 18h nobody is allowed to be in the streets. In order to travel to other cities, it is necessary to give valid reasons. Anyone who violates these requirements can expect a fine of 30 – 100 euros or even a prison sentence of 1-6 months. For people without papers there is very little chance of obtaining these permits. In a few cities, it was possible to get a permit if you went to the authorities accompanied by an employee of an NGO. Most people without a residence permit, however, have had to stay in their flats without any way of adequately meeting their basic needs. Travellers with regular residence permits also face discrimination when applying for travel permits. Many people have been denied such a permit in spite of their papers. As a result, travellers are often arrested by the police because they do not have the official documentation. Although the Moroccan State has announced several measures aimed at vulnerable populations, none of these measures have so far been taken in respect of the 80,000 sub saharan travellers living in the Moroccan state.

Covid-19 also fuels racism against people on the move, including abusive comments and even physical attacks on black people. On 5th of March, the weekly magazine, “Le Rapporteur”, chose to publish a photograph of a black young man hiding his face under the headline, “1st case of coronavirus in Morocco: who is responsible?” The first death, as the magazine editors well knew, was of an 87 year old woman of Moroccan nationality. At least this racist publication caused outrage on social media, but it displays once again the depth and openness of racism black people are confronted with in Morocco (and, for sure, elsewhere).

The situation of people in transit in Morocco was already precarious before the crisis and is now worsening. Most have no residence permit and work in the informal sector, at street markets or on construction sites. Many women with children have no other option than to ask for money on the street. These incomes have now disappeared completely and there are no alternatives. As a result, many people will no longer be able to pay their rent and will lose their accommodation. People are dependent on landlords to suspend or reduce the rent, which, fortunately, often happens.

Only people with Moroccan citizenship receive state support in the form of food rations; sub saharans and other nationalities (primarily Syrians and Bangladeshis) go away empty-handed. Small independent associations are trying to alleviate the misery by donating food, but this does not reach all the people in need. Again and again we hear from people, mainly single mothers, that they do not have enough food anymore and that they suffer from hunger. People suffering from chronic conditions have no access to care since hospital units are mobilized against the pandemic. This crisis is already having a devastating effect on the situation of people in transit. There’s no end in sight. The state of emergency has now been extended again until 10th of June.

2 Sea crossings and AP experiences

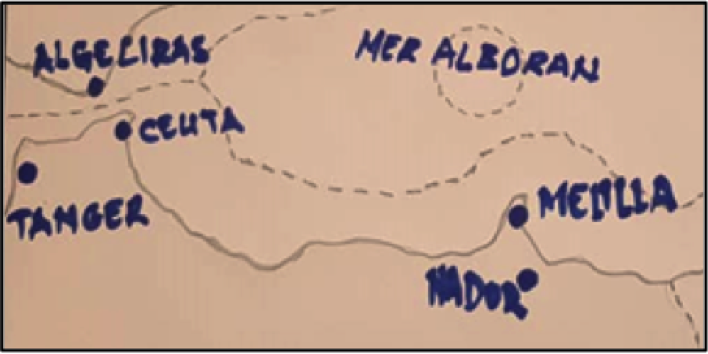

According to UNCHR data, as of 24th of May 2020, 7,266 people had arrived in Spain this year. 3,717 came via the Mediterranean Sea, 2,303 travellers arrived in the Canary islands and 1,246 crossings have been documented into the Spanish enclaves of Ceuta and Melilla.

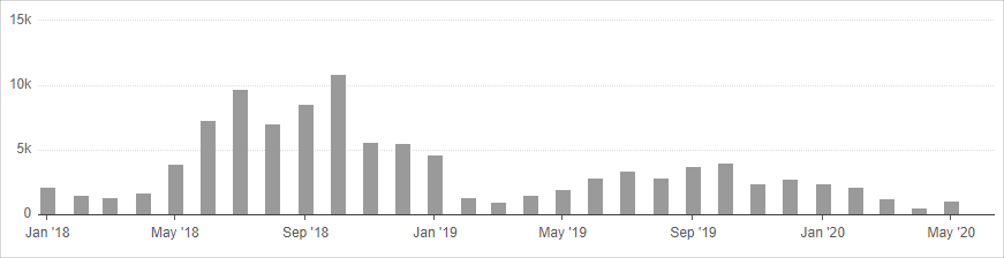

These numbers are comparatively low (except for the Canary islands). This is especially true of April in which only 542 crossing attempts were successful (in April 2019, 1,539 people managed to overcome the Western Mediterranean borders). The following graphic shows the changing pattern of monthly arrivals to Spain since 2018, as counted by the UNHCR:

The Alarm Phone was also less busy in the Western Mediterranean in comparison to the same period in previous years. Of the 7 cases the Alarm Phone dealt with, 5 boats were on their way to the Canary islands and two attempted to cross the Strait of Gibraltar.

For some Alarm Phone cases, the exact numbers of people on boats was difficult to confirm. However, our reports estimate that the 7 boats carried a total of 260 people who were attempting to cross to Spain. Only 2 boats reached the Canary islands, carrying 58 people between them. One boat eventually returned to Morocco. In the case of one boat of 36 people we were unable to confirm either arrival or return as we lost contact with them. At the end of March we had to follow up on a horrible shipwreck off Tan Tan. 43 people were lost at sea and only 21 people survived (mainly Guinean nationals). In the Strait of Gibraltar both of the groups of travellers who reached out to us were eventually intercepted by the Moroccan Navy. We had no calls at all from the Alboran Sea in the period covered by this report.

There are interesting reports of a new migration “trend” from Tarifa to Tangier: reversed sea crossings from Spain to Morocco. Different newspapers report that Moroccans are trying to organise their trip from Spain to Morocco to join their families during Covid-19. AP Member K. in Tangier reports that there is no reliable information on this phenomena at the moment. But we will continue to ask for credible information.

3 News from the regions

3.1 Tangier and the Strait of Gibraltar

On 8th of March 2020, the women of the local Alarm Phone team were involved in the organisation of the Women’s Day demonstration in Tangier. It took place in front of Cinema Riff at Grand Socco. Together with Moroccan feminists, Sub-Saharan women for freedom of movement, single mothers, and a few Europeans took the streets and sang slogans like ‘Solidarité avec les femmes du monde entier!’ ‘Raise your voice, seize your rights’ in Arabic and French. This day, about 800 women* formed a powerful and empowering march through the Northern Moroccan City.[1] No one imagined how, just a few days later, the upcoming pandemic would turn life in Tangier upside down.

Alarm Phone Members in Tangier report that the containment measures have further worsened the situation of migrants in the city. Crossings from Tangier to Spain have become next to impossible during this time. The Moroccan authorities systematically arrested every person on suspicion of leaving the country by boat. Travellers living in Tangier also suffer from the fact that it became impossible to beg for money in the streets, from not finding a place for the night and depending even more on the good will of NGOs. However, humanitarian organisations, like the rest of the country’s economy, are at a standstill. At the very beginning of the lock-down, the Moroccan authorities assisted migrants with food baskets and shelter in Boukhalef, a neighbourhood of Tangiers. But this assistance was not comprehensive and was short lived. The majority of travellers had to find shelter in the forests around the City. Faced with the government’s negligence, associations such as Caritas have provided assistance to migrants. Solidarity among fellow migrants has been powerful and effective. For example, K., an active Alarm Phone Member in Tangier, reports, “Even with my little money, I have helped migrants with small things but also by sharing my house with other women. During Ramadan, I offered soup and clothes to those who needed them the most.”

Concerning Sea crossings from Tangier to Spain AP Members in Morocco report: “The end of the lock-down is scheduled for June 10th, but in the meantime, we continue to monitor the movements of the migrants. We can say that crossings are nearly non-existent as the navy is on the lookout.” For the few who managed to “touch water”, they were quickly intercepted by the Royal Navy: We know of about 8 zodiacs in the last two months that tried to cross to Spain, and they have all been intercepted.[2]

While the number of deportations of sub-saharan people in Tangier had decreased before the lock-down started, the legal situation of the migrants has not changed at all. For the most part you are in an irregular situation and are still unable to avail yourself of your rights. This explains why, despite the Covid-19 pandemic, the terrible conditions that characterize the lives of people in transit in Morocco means that the focus continues to be on crossing the sea and reaching Europe.

3.2 Nador and the forests

Whilst the Covid-19 restrictions have been in place, not many people have been able to attempt the sea crossing from the region around Nador. Monitoring the Weekly Snapshots of arrivals to Spain, published by UNHCR, we see weeks without a Boza (“Victory” – the word for successful arrivals) recorded on any of the routes to mainland Spain. Few boats passed the heavy security, some groups were apprehended by the Moroccan forces while still on route to the coast. For examples, the Moroccan Human Rights Association, AMDH Nador, reports that around Bouareg, Nador, on 30th of April 26 people were arrested as were another group of 11 people the following day. Both groups were on their way to the sea.

Bekoya forest was attacked by Moroccan forces on 10th March. A camp of mainly women and children was destroyed and their phones and other belongings looted. Afterwards though, raids and arrests in the forests and makeshift camps of travellers around Nador seemed to decline until the middle of April, probably due to the first shock of Covid-19.

But from the middle of April, “Boumla” continued: AMDH Nador reports raids on 14th of April at Bekoya and Bolingo. Travellers were arrested without any respect to Covid-19 safety requirements. “Without complying with the standards of distance and non-assembly, these arrested migrants were loaded into vehicles in groups. The women with their children have just been sent back to an undetermined destination, while the men are still being held at the Arekmane detention centre” (AMDH Nador).

The Arekmane detention centre is a former holiday centre of the Ministry of Youth and Sports which the authorities have transformed into a detention centre. It is a site of struggle. The conditions of detention set by the law 02-03 concerning the entry and residence of foreigners in Morocco, which specifies the legal basis for and possible duration of detention, as well as detainees rights and due process, is completely ignored in Arekmane. This, it should be noted, is repeated in every other facility where travellers are detained in Morocco.

AMDH also reports raids on 15th of April at Afrah and in an area called ‘the carrière’. During these raids the camps, which at that time were mostly populated by women, were destroyed and burned by the Moroccan forces. On 22nd of April, 22 sub saharan nationals were arrested in a house in Beni Ensar and were brought to the illegal detention center in Arekmane.

Despite this, according to our local contacts, things seem much more calm. Many travellers have retreated to the forests to escape the tight Covid-19 restrictions and confinement in the cities. But even if the Moroccan forces have not looted the camps for some time now, the situation and living conditions remain extremely precarious. NGOs are often prohibited from delivering aid to travellers isolated in the forests of the region and, as the travellers cannot move freely out of the camps in order to have a chance to get food, many are suffering severely.

Political repression of any migration remains visible, even in these times of low crossing numbers. AMDH Nador reports on 11th of May that out of a group of 12 Senegalese nationals who had been arrested on 29th of April in Driouch, some 60 km southwest of Nador, 3 were accused of being ‘traffickers’ and have already been convicted to 1 and 2 months in prison as well as a 5000 MAD fine (around €500).

On 27th of April, the former president and current vice-president of the AMDH Nador, Omar Naji, was arrested by the Moroocan police after using Facebook to call out the confiscation of goods of street vendors in Nador. He is accused of defaming public forces and spreading false information. He was released after paying 10,000 MAD of bail one day later. The first hearing in his case is scheduled for 2nd of June. The arrest of Naji proves once again that media, including social media, is monitored in real-time by the Moroccan State, but, as Naji is a high ranking member of the AMDH, there is probably more at stake for the Moroccan State in these proceedings than the simple, truthful contents of Naji’s Facebook post.

3.3 The Western Saharan route

In the past three months, people travelling to Canary Islands have not only had to deal with Covid-19 and an increased level of police repression, but also with appalling weather conditions. Between the 5th and 20th of March, no boats were able to cross because of the meteorological phenomenon of Calima sandstorms. There were few crossings in mid-April, also as a result of bad weather conditions. Increased security measures and controls, not only due to the Covid-19 but also to political pressure, do not dissuade people from travelling but they do push departures further to the South, e.g. to Dakhla and Mauretania. This increases the duration and, therefore, the peril of the route. For example, the first boat arriving on the Canary Islands since the onset of the Covid-19 emergency had left a week earlier in Nouadhibou (northern Mauretania), carrying 45 people. Despite the level of danger and repression, many people do not have a choice but to travel, since living conditions in times of Covid-19 have only worsened in Morocco. B., an Alarm Phone activist in Laayoune describes the situation as follows:

“Migrants are really exhausted because of the state of emergency that Morocco decreed three months ago. This means people stay at home in order to respect the security measures, but it’s hard because their daily lives depend on informal business, there is no business activity, no revenue. If it wasn’t for acts of solidarity by certain organisations and associations who have helped, it would be catastrophic for migrants.”

Yet, the lockdown regulations and loss of income is not the only challenge for people seeking to cross to Canary Islands. There are ongoing arbitrary arrests in the streets (for allegedly not wearing a proper mask, being out in the streets in the evening, etc), and ‘quarantine’ arrests when boats try to leave the shores.

Arrest of travellers on Moroccan shores, 100 km away from Laayoune. Since Covid-19 is rampant, people are not freed after a few hours or days in a detention centre but are put under quarantine without any clear information on the duration of their detention. Source: Sahara Whatsapp Pictures

That means that dozens of people are held in makeshift detention centers that are clearly not compliant with any health standards. For example, more than 100 people were arrested and detained together in Laayoune in mid April, and around 140 in Dakhla in the same period. In early May, a brutal incident of police violence occurred in Laayoune. A fight broke out between some detainees and some cops (Force Auxiliaire). Shots were fired and four detainees were severely injured by rubber bullets. The injured detainees were taken to hospital but then condemned to a fine of 500dh (~€50) by the local judge. B. from Laayoune explains the reason for the unrest: “They had spent more than one and a half months in quarantine at the detention centre. Every day they were told that they could leave but that never happened. The migrants were fed up, this is what started the commotion.” Even at the time of writing, 78 people are still detained in the Foum-el-wad detention centre in Laayoune, and 4 people in Tarfaya without any information on when they will be released.

Despite the Covid-19 restrictions, despite the weather, people organise themselves and travel. By mid-May, 2,237 people had crossed to Canary Islands. This compares with 372 crossings between the 1st Jan and 31st of May 2019. That is to say, arrivals to Canary Islands are still more than 6 times as high as in the same period last year. This is in spite of external factors making departures more difficult. It comes as no surprise that more than a third of all arrivals in the Western Med are counted on the Canary Islands. According to the UNHCR, the travellers are mostly of Malian, Senegalese, Guinean and Ivorian origin, as well as some Moroccans. Around 20% of them are women, 12% are children – a much higher percentages than on other routes in the Western Med. Two truly heroic stories from some of these women and children have made it into the media: On the 28th of April, a baby was born at sea before the boat was rescued by Salvamento Maritimo, making it the third delivery at sea this year. Even more astonishing, a young girl named Mace (7 or 8 years old) managed to find her way to the Canary Islands alone, without any accompanying adult. While it is not rare to find unaccompanied minors among a group of travellers, workers in the Canary Islands were shocked at Mace’s very young age. Welcome to Europe to Mace and all the others who made it safely.

Mace, a very young traveller who made it to Canary Islands without any accompanying adult in late March. Source: José María Rodríguez (EFE) for Canaria7.es

However, so many who may have shared Mace’s dreams, plans and determination never made it across the sea. The route to the Canary Islands is still by far the most lethal route in the whole Western Med region. According to numbers cited by the ONG Caminando Fronteras, 245 people lost their lives between January and March 2020 on the Canary Islands route, which amounts to 85% of all deaths in the Western Med. (The official UNHCR data only mention 133 dead or missing for the same period). That is to say: Every week in January until March, nearly 20 people died en route to the Canary Islands, while around 125 arrived safely and an unknown number were intercepted by Morocco. 90% of all missing travellers have never been found and their relatives do not even have a body to bury.

The severity of the situation can be illustrated by the peak of crossings at the end of March. Between the 26th and 31st of March, Salvamento Maritimo was looking for a total of 11 boats. One of them foundered, only 3 out of 39 survivors were picked up by the Marine Royale. They were detained in Dakhla. Another boat was intercepted by the Marine Royale, and 5 boats were rescued by Salvamento Maritimo, one of them only after one full week at sea. But the fate of the remaining four boats remains uncertain. Unless there was some misinformation or counting mistakes, they almost certainly vanished forever in the depths of the Atlantic, carrying dozens of passengers with them.

Those lucky ones who do make it across the sea, however, by no means escape the dire Covid-19-induced situation they were already facing in Morocco. In late March, there were two positive cases in the Barranco Seco CIE on Las Palmas. This notorious centre re-opened last year, despite it’s terrible state. After the outbreak, a judge ordered its closure, but it took quite a while to relocate its inmates. While it’s a good thing Covid-19 has stopped deportations for the moment, there is a significant lack of personal protective equipment and space which makes it impossible to adhere to the safety measures. A police union has now called for a suspension of the usual 72 hour administrative detention period upon arrival since commissariats are not equipped to hold people in quarantine. New arrivals currently sleep on mattresses in old prison cells or even in the corridors between them. At the same time, transfers to the Spanish mainland have ceased. Paloma Faviedes, an expert on asylum law, accuses the government of pursuing a policy of deterrence: “The message the government wants to send is clear, although nobody says it out loud: entering the Canary Islands is not the same as entering Europe”.

3.4 Oujda

On 10th of May about 20 people, who had been deported from Nador to Algeria, reached out to members of the Alarm Phone. They sent a video showing that they had been thrown out in the mountains and had had their phones and money stolen by the Moroccan Forces Auxiliaires. When they were brought to the Algerian territory, the border police took what was left. As well as there being a pandemic, it was Ramadan and the people, dumped in the middle of nowhere, were confronted with the problem of how to get food and support. We couldn‘t re-establish contact once all of their their phones had been stolen. About one week later we heard that some of them managed to make it to Oujda, others are said to have continued to Oran in Algeria. We have not yet managed to get back in touch, but we will follow up this life threatening and illegal push-back.

In the last three months, according to health association workers, there were more arrivals from sub-saharan travellers in Oujda than before. It is assumed that, in times of Covid-19, there is more support and even better living conditions in Morocco than in Algeria. This makes migrants cross the border. The age of the travellers is also notable. Many of the migrants who gather to ask for money in the streets are adolescents or children.

The health conditions continue to be severe. Most of the people who ask for health services have problems because of bad nutrition and unhealthy living conditions, especially after long periods of travel. Many of the women who seek medical support also do so because of sexual violence.

On 18th of May, two people of Guinean origin died in the trench which is part of the Moroccan-Algerian border. Police say that the two were believed to be involved in hashish smuggling and died when they fled the police. Unfortunately there is no more information so far.

3.5 The enclaves: Ceuta and Melilla

Official figures concerning ‘irregular’ entries into the Spanish enclaves are currently contested. According to the latest figures of the Ministry of the Interior of Spain, from the beginning of 2020 until 15th of May, 1,243 people entered the enclaves irregularly via land, which is a 42% drop compared to 2,147 in the same period last year. The ministry registered no sea arrivals to Melilla and only 45 entries to Ceuta, a 77% drop. However, although the figures show otherwise, in at least one case, two people from a group of four managed to swim into Melilla and the Government Spokesperson recently talked about a few arrivals via the sea. On the other hand, the recorded sea entries to Ceuta actually correspond to cases in which people embarked from Ceuta aiming for the Peninsula, but were brought back by SM. They should not in fact count as new arrivals to Spanish territory.

Nevertheless, the overall drastic decline in entries must be seen as an effect of the ongoing developments we have already reported on, and, in particular, the ever increasing securitization and militarization of both sides of the border. Although activists indicate that they have been in use for years, for the first time the Spanish Guardía Civil publicly acknowledged the use of thermal cameras by the Tax and Border Patrol (Pafif) in border monitoring. From mid-March 2020, the measures to prevent Covid-19 not only led to the closure of all border posts until Mid-June, but were used to legitimize the surveillance program and to push further militarisation. Military from different units in Ceuta and Melilla started to patrol at the border for the first time since 2005 in order to reinforce the Guardia Civil. Since then, Units of the GRS (Grupo Rural de Seguridad) are responsible for the control of the fence on a routine basis.

Yet, despite these enormous efforts to control and secure the border, 126 people managed to enter the enclaves via land since the closing of the border (107 into Melilla, 19 into Ceuta). On 6th of April, the same day the military operation was officially launched, in a collective attempt by 260 people, 55 jumped the fence into Melilla. Several people were taken to the hospital with bone fractures, 2 people were arrested. Another 38 people were unlawfully deported to the Moroccan state. On the Moroccan side, AMDH reports that numerous people returned to the nearby forests with untreated wounds. Another attempt to cross the fence into Ceuta was prevented by the Spanish Guardia Civil. On 21st of May a Sub-Saharan minor had already managed to get across the razor blade wire when he was pushed back and handed over to the Moroccan authorities. We condemn, along with 11 organizations from Spain, the government for this ‘Devolucion en caliente / hot deportation’ of a minor – they are acting brutally and illegally as they are violating Spanish law, the European Human Rights Convention, and Art. 3 of the Convention on the Rights of the Child.

On 13th of March, overnight Morocco closed its borders completely – even to Moroccan citizens who were abroad. At the same time, the Spanish government implemented measures to prevent the spread of Covid-19. This has led to a worsening of the situation for travellers who are stuck in the enclaves on their way to Europe as well as for many who are prevented from continuing their travels into Morocco. The people already sleeping on the streets or in the harbour areas, as well as the newly arriving and trapped Moroccan citizens were left without any support by the state. With the help of solidary organizations or individuals, neighbourhood associations and NGOs, they found shelter in mosques or were accommodated in garages, warehouses, private houses or industrial buildings throughout the city. Later on, some were transferred to the already overcrowded emergency housing or improvised shelters, like sports halls and tent camps. Currently, the Centro de Estancia Temporal de Inmigrantes (CETI) in Melilla, with a capacity for 580 people is holding around 1,700 people, including children, women and LGBTQI+. The centre for unaccompanied minors in Melilla ‘La Purisima’ with a capacity for 180 people has been holding about 900 minors. As is repeated across the world, during Covid-19, accomodation in centres or camps exposes migrants in overcrowded centres to a high risk of infection. There is no possibility for social distancing and no access to masks. Additionally, queues for sanitation and food supplies are long. There is often no access to Wifi, no possibility to leave violent or abusive situations, and insufficient consideration of people under psychological stress, different vulnerabilities or risk groups.

An especially vulnerable group hit by the lookdown are unaccompanied minors (MENA, Menores extranjeros no acompañados), many of whom live in the streets and harbours, as they seek asylum in the Spanish enclaves. In the wake of the lockdown, Spanish authorities claimed that they will “ensure that young people and migrant minors who are not in the CETI or in the city’s reception centres are confined to sites “for their own protection and that of others.” Even in times without Covid-19, the centres for unaccompanied minors ‘La Purisima’ (Melilla) and ‘La Esperanza Centre‘ (Ceuta) are constantly overcrowded. The NGO RedMelilla accused the government of failing to provide support, thereby putting over 900 minors at the risk of infection. Albeit at a late point, some minors were transferred to other camps or parts of the respective cities. 200 MENA from ‘La Esperanza’ were meant to be housed provisionally in tents set up by the military but the camp was destroyed by a storm – luckily, nobody was yet living there. Despite the obvious risks, the Comandancia General de Ceuta (COMGECEU) deployed several military personnel to set up the unstable camp again. In the light of these inadequate measures to provide safe living conditions, the government obviously failed in its efforts to ensure the MENA a “quarantine in the same conditions as other citizens”.

In general, the state response to do away with the inhuman conditions in these centres has so far been either insufficient or used to reinforce anti-migrant policies. Over the course of the last two and a half months 329 people were permitted to cross over to the Peninsula. While this is the biggest departure of such kind in years, it left many behind who have had their journeys delayed for months or even years. This discriminatory arbitrariness led to many protests and an 18 days hunger strike in the CETI in Ceuta. The actions were not acknowledged by the State and remained without consequences. Promises to house people away from the CETIs were barely implemented, while protests in the CETIs and the Centres for unaccompanied minors against the living conditions were met with heavy police repression. Furthermore, at the end of April Grande Marlaska, the Minister of Interior, threatened to deport 600 travellers to Tunisia – this would clearly violate European Human Rights Convention Art. 4 against collective deportations (as many organisations claimed in an open letter). It led to protests and hunger strikes by Tunisian travellers, with strikers filming themselves sewing their lips together to underline their action.

Two months after the complete lockdown by Morocco, on the 15th of May the process of repatriation of Moroccan citizens was started, but only after a woman stuck in Melilla had died in one of the city’s shelters. Moroccan officials have been handing over lists of people that are allowed to cross into Morocco to the Spanish government. How these lists are put together is very opaque. On the one hand, some waiting desperately to go to Morocco are not included, and on the other, people who do not want to go back, hoping instead to reach the Peninsula, are. They fear getting deported against their will. At the time of writing, Spanish authorities are opening forced eviction proceedings.

Nevertheless, throughout these last few months, hundreds of people have protested against the racist consequences of the responses to Covid-19 and for a full implementation of the right for asylum and freedom of movement. The strategies used include hunger strikes, open letters, (online) campaigns demanding the release of those still in CIEs and in the CETIs of Ceuta and Melilla, their transfer to the Peninsula, the permanent closure of all camps/centres and the final prohibition of (hot) deportations. Many organisations and individuals continued to act in direct solidarity, providing food, shelter, warm clothes, blankets and first aid. And, as demonstrated by the case of four Moroccan minors who swam back to Morocco, people continued to subvert borders, one way or another.

“In order to overcome this health crisis we have to be all together, in equal conditions!”

Source: Twitter Miguel Urban

4 Shipwrecks and missing people

On 2nd of March, 26 people left from Dakhla and have been missing ever since. Alarm Phone couldn’t find out what happened to the boat

On Thursday, 12th of March, 8 people die in a boat which originally carried 47 people between Asilah and Larache at the Moroccon West coast, as reported by Caminando Fronteras.

On Thursday, 26th of March, a boat with 39 people on board capsized off Dakhla. Only 3 survivors were rescued. Most victims are nationals of Ivory Coast.

On Friday, 27th of March, 22 people are presumed to have drowned off Dakhla, while only 7 people could be rescued by fishing vessels. One women dies shortly after arriving at the shore.

On Monday, 30th of March, 3 people from a group of 16 sub-saharan travellers drown off Mostaganem, Algeria.

On Friday, 3rd of April, a boat carrying mainly Guinean nationals, shipwrecks 24km off TanTan on its way to the Canary islands. Only 21 people survive. 2 bodies were found and 43 people remain missing.

On Wednesday, 15th of April, a body, later identified as Egyptian national Mohamed Youssef, washes ashore after he attempts to reach Melilla.

___

[1] Check our Report: Struggles of women* on the move: https://alarmphone.org/en/2020/04/08/struggles-of-women-on-the-move/

[2] See Chapter 2 on “Sea Crossings” in this report.