Rally in Dakar on November 21 to commemorate the dead and missing. Source: AP Maroc

Rally in Dakar on November 21 to commemorate the dead and missing. Source: AP Maroc

Content

1 Sea Crossings and AP experiences

2.2 Tangier and the Strait of Gibraltar

2.3 The enclaves: Ceuta and Melilla

2.5 Oujda and the Algerian borderzone

4 Shipwrecks and Missing People

Introduction

2020 was a difficult year for people all around the world. Travellers on the routes across the Western Mediterranean and the Atlantic were no exception. They faced numerous novel challenges this year. We witnessed unprecedented developments. In Morocco and Spain, not only has the Corona crisis served as yet another pretext to harass, intimidate and mistreat migrants, but the travel routes also changed significantly. Now large numbers of people leave from Algeria to reach the Spanish mainland (or even Sardegna). This is why we have started including an Algeria section (see 2.6) in these reports. Secondly, the number of crossings to the Canary Islands exploded, particularly in the last three months. As in 2006, during the so-called “crisis de los cayucos”, when more than 30,000 people reached the Canaries, boats are leaving from Western Sahara, but also from Senegal and Mauritania. For this reason, we have renamed our Canary Islands section, “Atlantic Route” (see 2.1).

The numbers of arrivals on the Canary Islands is nearly as high as in 2006. With more than 40,000 arrivals in 2020, the boat journey to Spain has become the most frequented travel route to Europe. At the same time, it includes the most lethal one: the Atlantic route, towards the Canary Islands.

These developments are terrifying. The sheer number of dead and missing people leaves us speechless. Every three months, we compile a list of the dead and missing (see section 4), and for this report, it has become insanely long. We stand in solidarity with the relatives and friends of the deceased, and with the survivors of this ordeal. With this report, we want to highlight their struggles. We have deep respect and gratitude for all the freedom fighters on the ground who continue to struggle for freedom of movement and human dignity for all.

There are many inspiring examples of those struggles on land, at the borders, at sea and in detention centres.

In Spain, the government is trying its best to curb migration (see section 3). They cannot stop people moving and so all they have achieved is the spectacular failure to provide decent accommodation for the new arrivals. Nevertheless, within the Spanish state there are many who fight for migrants’ rights and dignity. We were inspired by the commemoraction organised by some inhabitants of Órzola, after the death of 8 travellers on the rocky beaches of northern Lanzarote. They are not alone. Lanzarote citizens have published a manifesto, demanding decent treatment for anyone arriving on the island, be it tourist or boat-traveller We echo their claim that it is important not to be infected by the “virus of hatred”.

We also salute the solidarity networks that support people on arrival on the other islands. One example is the network that organised the march “Papeles para todas” (papers for all) on 18 December on Gran Canaria.

Resistance also occurs inside the detention centres (CIEs). In October, there was a protest held on the roof of the building and a hunger strike organised by detainees of the Aluche CIE (Madrid), after the detention centre reopened in September.

Lastly, we want to highlight the courageous struggle of the CGT, the majority worker’s union of Salvamento Maritimo, whose members have long been fighting for more staff and better working conditions for the coastguard through their ‘Más Manos Más Vidas’ campaign. They have repeatedly criticised the government for pumping money into migration control, whilst failing to provide sufficient funds for the coastguard to be able to do their job properly and prevent the burn-out of their staff.

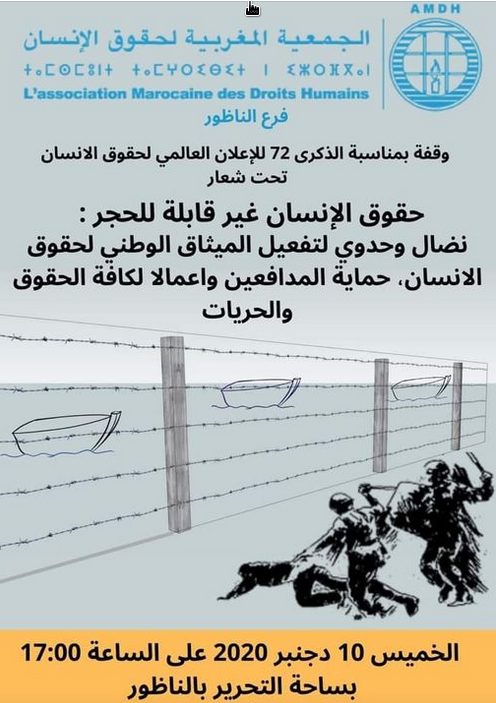

In Morocco, several activists have called out the human rights violations of the Moroccan government, criticising discriminatory practices like expulsions and deportations, but also decrying the stigmatisation many Black people have to endure in the Kingdom. The ongoing harassment of migrant people was also voiced at the sit-in organised by the AMDH Nador on 10 December, when activists rallied in the “Tahrir”-Square in Nador to demand free speech, freedom for political prisoners and respect for human rights.

Sit-in organised by the AMDH on 10 December 2020. Source: AMDH Nador

Sit-in organised by the AMDH on 10 December 2020. Source: AMDH Nador

Likewise, in a joint communiqué and in a letter to the Ministry of the Interior, several associations (Euromed Droits, AMDH, Caminando Fronteras, Alarm Phone, Conseil des Migrants) spoke out against the negligence of the Moroccan authorities when it comes to sea rescue.

Moroccan travellers have also raised their voice against the deplorable human rights situation in their country (see testimony in section 2.1) but also against the deplorable conditions they face once they arrive in Spain, a prime example being the lack of basic necessities in the harbour camp of Arguineguín.

In Senegal, people organised after the numerous, horrific shipwrecks in the second half of October. The Senegalese government refused to acknowledge the high numbers of deaths (Alarm Phone estimates up to 400 people dead or missing between the 24th and 31st of October, see section 4). When activists and young people wanted to organise a demonstration, any such action was forbidden or impeded by the authorities. Nevertheless, three weeks later, a rally was organised in Dakar under the slogan “Dafa doy” (It’s enough!). Activists and relatives got together to commemorate the dead. During that period, numerous people in Senegal were active on twitter, tried to organise prayers and spoke out against the mismanagement of the Senegalese government and the unspeakable, unnecessary deaths.

Call-out to the rally in Dakar on 21 November 2020. Source: AP Maroc

Call-out to the rally in Dakar on 21 November 2020. Source: AP Maroc

1 Sea crossings and AP experiences

In 2020 there were 41,094 arrivals recorded in the Western Med, a higher number than in other regions of the Mediterranean sea. According to the UNHCR, of these cases, 71% travelled to the Canary Islands, 22% to the Peninsula and 7% to the Balearic Islands. Caminando Fronteras Collective states that, in comparison to last year, arrivals in Spain increased by 28.7%, however, the number of deaths increased by 143%. This figure makes 2020 the year with the most recorded deaths. From our experience, these elevated numbers are a result of the fact that the Spanish coastguard do not commit, or even have, enough resources to monitor the huge SAR zone, particularly when boats leave from very far South. Despite the valiant efforts of many Salvamento Maritimo employees, more staff and resources are needed to respond to the huge increase in boat departures. It remains the case, however, that the increased danger of the journey is down to the negligence of the coastguard, particularly the Moroccan, but also their Spanish counterpart. This criminal neglect can have lethal consequences. It often does.

Between October and December 2020, Alarm Phone assisted 60 cases in the Western Mediterranean and Atlantic region. This shows an increase of more than 50% in comparison to the 39 cases Alarm Phone handled in the winter of 2019. Of these cases, 44 resulted in a safe arrival in Spain, while six boats ended up back in Morocco/Western Sahara (two returned autonomously while four were intercepted by the authorities). Two boats were declared missing and two more were left shipwrecked. Despite Alarm Phone’s effort to track the cases, the fate of the remaining six boats remains unclear.

Some Alarm Phone cases from the past four months

One shipwreck we want to highlight is of a boat carrying 13 people (including nine women and one child) on 6 December. The boat developed engine problems just off the Moroccan coast. Authorities were alerted and conducted a search mission, but in vain. The following day, the remains of a rubber boat were found on the Moroccan shore with two survivors and two bodies on board. The rest of the passengers were missing.

A man, who lost his wife in this shipwreck and had been in touch with the Alarm Phone, wrote down his testimony. He explains how he tried and failed to push the Moroccan Navy into action:

“I want to denounce the Moroccan authorities.

I witnessed the scene from the beginning until now.

They saw them die with their eyes and did nothing to save them.

I did everything, I told them “Sorry, but there’s a baby in the boat!” They didn’t do anything.

I sent the location to the Moroccan navy at 11pm and they didn’t move their ship.

If you want to help, help me be seen by the media, I want to denounce them publicly.

It is a country of racism. In this country, I have already lost a lot of my friends at sea.”

The second shipwreck occurred on December 23 about 14 NM off the coast of Laayoune (officially in Spanish SAR zone). Spanish and Moroccan authorities were informed, but failed to act quickly enough to carry out a rescue. The boat carrying 62 people was shipwrecked, 45 people survived, one body was found and 18 people went missing. We send our solidarity to the families of those lost in this shipwreck. Let this event be yet another reminder of the fact that Europe’s borders kill people.

2 News from the regions

2.1 Atlantic Route

When we wrote our last analysis, we described the huge increase in arrivals. Back then, sometimes hundreds of people arrived within one or two days. We now have to talk of thousands of arrivals within a few days. In the past three months, around 16,000 travellers have made it to the Canary Islands. This is more about two thirds of the 22,249 people who made the journey in 2020. Each and every one of them spent days at sea, covering hundreds or thousands of kilometres without GPS, often without enough food and water. They survived what is the most lethal route to Europe. We warmly welcome and salute them all – we stand in solidarity!

We also mourn all those who lost their lives in the vastness of the Atlantic Ocean. The IOM counts 593 deaths so far for this year, but we believe the number to be much higher. Just looking at the last three months, from the boats that reached out to us, we can count 100 people whose fate is unclear. If we include the dead and the missing from the shipwrecks we heard about from local activists in West Sahara and Senegal, we have to add another 150 to 300 people. If we add up those numbers we already have another 250-400 dead/missing, only from the past three months. It therefore seems impossible that the IOM figure is accurate, it must be much higher. The Red Cross estimates that around 5-8% of all boats vanish without trace, bringing the number of dead and missing to around 1000-1700 for 2020. The Spanish NGO Caminando Fronteras has counted 1851 deaths. Given our numbers and these estimates we feel it is not exaggerated to assume that the death rate on the Canary Islands route is at least 1 person from every 12 who attempt the crossing.

On 23 October 2020, a boat carrying approximately 200 people capsized off the coast of Mbour, Senegal,

On 23 October 2020, a boat carrying approximately 200 people capsized off the coast of Mbour, Senegal,

after the engine had exploded. Only 51 people were saved by fishermen and the Moroccan Navy.

Source: AP Maroc, video taken by Senegalese fishermen

Out of all distress calls we have received, one recent event warrants special attention: in AP case 591, unusually we were able to receive a position of the boat in distress. The boat was carrying about 56 passengers (later turned out to be more). We received the position at 23:41, on 23 December, and immediately alerted the Spanish and Moroccan authorities. The position showed the boat to be 14 nautical miles (~26km) off the coast of Western Sahara. Because this area is officially a Spanish SAR zone (an artefact of the former Spanish colonisation of Western Sahara), we assumed Salvamento Maritimo to be the competent authority. However, this was denied by the SM. Neither the Spanish nor the Moroccan coastguard came to the boat’s rescue. The result was catastrophic. With only 44 survivors, though one person later died in hospital, and 18 dead/missing, the shipwreck is one of the deadliest of this period. These deaths could so easily have been avoided!

Position of the boat carrying 56 travellers, in the Spanish SAR zone. Source: Alarm Phone

Position of the boat carrying 56 travellers, in the Spanish SAR zone. Source: Alarm Phone

There has been a tremendous increase in boats from Senegal and Mauritania. In the first weekend of November, nearly 2000 people arrived on the Canary Islands within 48 hours (a record high), many of them on wooden fishing boats (so-called “cayucos”) from Senegal and Mauritania carrying a hundred or two hundred people. This uptick in people leaving from Senegal is largely attributed to the Covid-19 crisis. Increased poverty, unemployment and the closed terrestrial borders with Morocco leave many people with little other choice than to risk the dangerous 1500km boat journey from Senegal to the Canaries. Many of them do not make it to the Canary Islands since they run out of fuel, run out of water, or get lost on the way. If they are lucky, they end up in other countries, such as Mauritania, Western Sahara or in Cape Verde. This is what happened to the 70 survivors of a boat on 16 November whose engine exploded. 60 to 80 more people are missing/dead. Alarm Phone activist A. accompanied the survivors of one such shipwreck on 14 November:

There are also arrests when people try to migrate. There was a boat that had left Mauritania on 4 November, with 63 people. 12 of them were lost at sea during the journey. They [the remainder] didn’t have food or water for nine days and [when they] landed on the shores of Boujdour [Western Sahara] on 14 November, there were 51 people, out of whom 3 were women. They were picked up by the military and were taken to the detention centre in Boujdour.

The survivors of a shipwreck arrive on the shores of Western Sahara. They are later taken to a detention centre.

The survivors of a shipwreck arrive on the shores of Western Sahara. They are later taken to a detention centre.

Source: AP Maroc

Yet, the difficulties for many travellers begin directly upon departure. By trying to intercept boats in Senegalese waters, the Senegalese state is complicit in the European border system. In the night of 25./26. October, the Senegalese Navy intentionally and forcefully hit a boat whose captain refused to stop. The boat was carrying more than 80 people. It had left from Soumbédioun (Dakar). An eye witness reports:

“When the navy saw us, they tried stopping us. We were close to an island (Madelaine) and the captain tried to go there to land and avoid going to prison. The Senegalese Marine Nationale asked twice that we stop, the captain continued. The Marine hit us with their boat and didn’t rescue anybody until the Spanish navy arrived. Together, the Marines saved 39 people, all the others died drowning. I spent three hours in the water before being rescued.”

Senegal is also using other means for deterring people from leaving. The father of a 14-year-old boy who died on the Canary Islands route and another two parents whose children survived are now on trial for being “complicit in trafficking migrants”; their defence lawyers accuse the prosecution of demanding excessive sentences for the purpose of deterrence.

But people reach the Canary Islands, even from countries much farther away than Senegal. The Spanish newspaper El Pais describes how people spend weeks hiding in the tiny space above the rudder of huge cargo ships, coming from countries such as Nigeria. 20 people have arrived on the Canary Islands since August by this extremely dangerous means, but there is no way of knowing how many have died in the attempt.

Among the travellers there are also many Moroccan nationals. They constitute around half of all arrivals on the Canary Islands. They flee the country because of unemployment and lack of opportunities, or because of political persecution and because they cannot speak freely. O., one of the freedom fighters who recently arrived on the Canary Islands testifies:

The first thing I want to say is, I am sad. Because I lost friends who tried to come here, too. But the sea won, they are now in heaven. […] The situation in Western Sahara is a joke. The government doesn’t listen to any calls of help from migrants. They don’t send a rescue unit. They want us to die, they don’t care about us. That’s why we run, they don’t see us as humans. They see us like dolls with strings.

Situation on the Canary Islands

The situation on the Canary Islands is abysmal for arriving travellers. Thousands of people are living in makeshift tents on some stretches of tarmac. The harbour of Arguineguín (Gran Canaria) has become known internationally as the “dock of shame”.

The overcrowded harbour of Arguineguín. Source: Javier Bauluz

The overcrowded harbour of Arguineguín. Source: Javier Bauluz

The camp was dismantled in November. Around 2,600 people were staying there temporarily, although the capacities were originally limited to 400 people. NGOs have long decried the lack of services, e.g. legal advice, interpretation, basic hygiene, adequate distancing measures and other things. There were serious human rights violations. For example, lawyers signed deportation orders without even once talking to their clients or without interpreters being present. Human rights activists considered the camp to be illegal as, under Spanish law, arriving travellers must be liberated after 72 hours. They are not to be kept in pens for more than 15 days.

Now that the camp has been dismantled, some of the residents have been relocated to makeshift tent cities, e.g. on the compound of the CIE Barranco Seco, a dilapidated former prison building. Although the makeshift camp is supposed to offer space for 800 inhabitants, it only has 200 beds. The NGO Médecins du Monde points out that this interim accommodation replicates the situation in Arguineguín, as the people are still shut away and NGOs do not have enough access to provide services. According to them, the military camp perpetuates a “model of criminalisation” where residents are treated like detainees rather than bearers of human rights. Some residents of Moroccan origin have already spoken out about the lamentable conditions. They explain that there are no shower facilities, that the residents were not given any clothing or bedding appropriate for the cold and damp November weather, forcing them to remain in the shirts and shorts they wore upon arrival.

Weeks ago, the police union, JUPOL, asked for more staff and resources to be allocated in the light of the dramatic increase in arrivals. In mid-December, the government approved 83 million Euros to help deal with the humanitarian crisis on the Canary Islands. This is still very little compared to the hundreds of millions that Spain pays to the countries of departure to prevent people exercising their right to move. The Spanish government is now planning to build seven emergency centre to shelter the thousands of newly arrived people. Four are to be located on the island of Gran Canaria, two on Tenerifa and one on Fuerteventura. This approximately mirrors the distribution of new arrivals. 65% of travellers are rescued to Gran Canaria, 20% to Tenerifa and 10% to Fuerteventura (the remaining 5% goes to other islands of the archipelago). The first of those seven emergency camps with a capacity for 300 people was finished late December.

Meanwhile, it has become impossible to continue the journey to mainland Spain, the government has closed airports to all people who arrive irregularly. While it used to be possible to buy a plane ticket with a foreign (e.g. Moroccan) passport, people now cannot continue their journey to the mainland, turning the Canary Islands into an island-prison in the midst of a humanitarian crisis.

Situation in Western Sahara/Morocco

In the cities of Dakhla and Laayoune, and on the beaches of the Atlantic, the Moroccan authorities continue their programme of harassment and forced displacement. Although deportations to the Mauritanian border have stopped, Black people are frequently taken to cities of the North, e.g. Agadir and Tan Tan, hundreds of kilometres away from their homes. Alarm Phone activist B. also underlines how difficult it has become for foreigners to sustain themselves economically:

The migrants that work in the factories [fishing, port activities] have been banned from going back to work. Those who are earning money with some small business (in the informal sector) are still being arrested, and their goods are confiscated.

Black people are sometimes also stigmatised as bearers of the Covid-19 virus, which is why sometimes employers have refused to re-hire them after the lockdown measures were eased. Human rights advocates on the ground have a clear demand from the Moroccan authorities: extend the validity of all residence papers, even if the holder lost their job due to the pandemic.

In addition, the Moroccan authorities have significantly pushed forward their securitisation agenda in Western Sahara. Alarm Phone activist A. reports:

Along the coast of Laayoune, there are small structures with surveillance posts at short, 2km intervals. Some tents have even been erected between these surveillance posts, in particular in places that are considered to be frequently used as points of departure.

Lastly, these three months have seen a reversal of policy when it comes to deportations. In September and October, after the Covid-19 restrictions had been eased, Morocco organised a number of deportation flights from the airport in Dakhla. These flight were carried out in collaboration with Guinean and Senegalese authorities and resulted in the deportation of African citizens of different nationalities, among them even women and children. Since then, Morocco seems to have stopped this practices, reverting back to forcefully relocating travellers within the territory it claims to control after intercepting them on boats and locking them up in detention centres.

The survivors of the shipwreck from 23 December are taken from the hospital to a detention centre. Although they spent 4 days on the water and saw 18 of their fellow travellers die, they did not receive proper care (food, water) by the Moroccan authorities. Source: AP Maroc

The survivors of the shipwreck from 23 December are taken from the hospital to a detention centre. Although they spent 4 days on the water and saw 18 of their fellow travellers die, they did not receive proper care (food, water) by the Moroccan authorities. Source: AP Maroc

2.2 Tangier and the Strait of Gibraltar

Tangier, the former migration hub and jumping-off point for sub-Saharan travellers trying to reach Europe via the narrow Strait of Gibraltar, became, in the last months, a place of less visible violence. Alarm Phone Activists from Tangier report that, compared to recent years, fewer and fewer sub-Saharan travellers are staying in the port city. This does not stop the Moroccan authorities from continuing to search their homes without notice, arresting people on the basis of racial profiling, and expelling or detaining them. The repression in Tangier, the reinforcement of the military on the north coast, the increased forced displacement within the country and even deportations to people’s countries of origin has led to a steady shift of the route towards the south. This is a phenomenon that these reports have already noted.

The number of crossings to Europe is relatively low, not only because of the bad weather, but also because of the draconian security measures violently implemented by Moroccan auxiliary forces in Tangier and its surroundings. Nevertheless, some dare to attempt the journey to Europe. The Alarm Phone accompanied three boats which left from this region. On these boats were men, woman, children and babies. All of them where brought back to Morocco.

Some travellers managed to make their way to Europe. On 25 October, Helena Maleno reports that, a convoy with 7 people starting from Tangier arrived safely in Algeciras. In October alone, activists and NGOs have identified eleven convoys which started from the area. They carried 144 people. But the month also saw the horrific discovery of a body in the Strait of Gibraltar. This month, according to our knowledge, at least 71 people arrived in Algeciras, as detailed in Helena Maleno posts: 01.10. “#BOZA convoi avec 10 personnes sorti Tanger arrive Algeciras”, 01.10. “#BOZA convoi avec 6 personnes sorti Tanger arrive Algeciras”, 10.10. “#BOZA convoi avec 24 personnes arrive Algeciras”, 12.10. “#BOZA convoi avec 17 personnes sorti Tanger arrive Algeciras”, 17.10. “#BOZA convoi avec 14 personnes sorti Tanger arrive Algeciras“, 33 people in Ceuta (01.10. “2 convois avec 4 et 13 personnes sorti Tanger arrive Ceuta”, 16.10. “2 convois with 9 and 7 people arrive in Ceuta“) and 22 people in Cadiz.

The members of AP Tangier, often themselves in precarious conditions, are actively engaged in supporting people in these difficult circumstances. They bear witness to the fact that people continue to wait in arduous conditions, often forced to beg for money on the streets to survive. Exploiting the precarity of the migrant population, the Moroccan authorities attack it violently and systematically. The few people who choose to remain in the city risk raids and deportations.

Even if now there are comparatively few sub-saharan travellers in the city, authorities do not miss any opportunity to use violence against those that remain. Alarm Phone Members believe it is chiefly about intimidation and the desire to push as many Black people out of the city as possible. In the two last months more and more frequent raids were reported. According to the local AP team, there are currently deportations of Senegalese nationals. On September 29, several men were arrested in their home in the area of Boukhalef, and deported to Senegal. Local activists reported several arrests in the forests around Tangier, and were informed about deportations to Mali. The harsh situation is causing many people to leave towards the South (Western Sahara, Mauretania and Senegal) to attempt to cross.

For many years there has been a group of Alarm Phone activists in Tangier who constantly report from there and talk to people on the ground who want to leave Morocco. Local AP members explain how the Alarm Phone works and share other emergency numbers which can save lives. In recent months, we have observed that the city of Tangier has become increasingly quiet. But this silence is misleading, because as we know, people on the move continue to suffer from ongoing structural racism and violent migration management by Morocco and the EU. Even if it is not very visible, people are still trying to fight for their right to freedom of movement and start from Tangier, the gateway to Europe, to Spain.

2.3 The enclaves: Ceuta and Melilla

On the Spanish side, when Morocco closed its borders with Ceuta and Melilla in March 2020, hundreds of Moroccans got stuck in the enclaves for over half a year. Repatriation only started at the end of September and then only proceeded at a snail’s pace. On the other side, 9,000 Moroccan families were affected as workers who used to cross the borders on a daily basis were now prevented from entering the enclaves. As of today, the workers have still not received any compensation for their lost income. This forced unemployment and the probable loss of legal jobs has led to an increase in attempts to reach the enclaves via the sea, especially to Ceuta.

Between the end of September and 27 December, 513 travellers had reached the enclaves (299 to Ceuta, 214 to Melilla), adding up to a total of 856 arrivals to Ceuta and 1,485 arrivals to Melilla in 2020 (UNHCR). Whereas in 2019, most travellers reached Ceuta via land, this year nearly all border crossings happened via the sea. Since July, more and more young people have tried to swim to Ceuta from Fnideq (Castillejos), a Moroccan city about 600m from the border. Depending on the starting point, it takes between three to five hours to reach Ceuta. According to Spanish security forces, about five people per day try to swim to Ceuta, some wear wetsuits and flippers. Most swimmers prefer to leave at night and to avoid the border zone as the Guardia Civil scans this area with infrared detecting cameras.

Those who arrive in Ceuta, be it with boats (e.g. 25 December ), on ships (e.g. 5 December ), hiding in (refrigerated) trucks (e.g. 20 December) or by swimming (e.g. 21 October , 12 December ), and are intercepted by the authorities have to spend a 10-day quarantine on a ship located in the Tarajal district. But many people do not survive this highly risky route (see section 4). For the most part they are driven to take this riskier route because the land border is becoming more and more militarised.

Although the construction of the ‘less bloody’ double fences around the enclaves (see our last reports) continues, some stretches of the new system are still not finished. Morocco, however, is much faster in using its subsidies to reinforce its borders with Spain with barbed wire and trenches. This also pushes people onto the route to the Canary islands and directly to the sea. However, there are some examples that show that crossing the land border is still possible and that people are still risking their lives to do so. Two people arrived in Ceuta by climbing over the new fence, one on 3 December and one on 11 December .

Unfortunately, on 20 November, the Constitutional Court endorsed, almost in its entirety, the Citizen Security Law (Ley de Protección de la Seguridad Ciudadana, LOPSC). This gives legal support to the long established practice of the so-called ‘hot deportations‘ of people at the fences. It must be noted that a ‘hot deportation’ occurs without the person concerned being able to claim asylum, let alone have her claim investigated. To a non-lawyer, this is a clear breach of principle of non-refoulement. The court ruled against these immediate deportations only as long as the entry is ‘individualised’ under ‘full judicial control’ and in ‘compliance with international obligations’. It is clear that nobody seeking international protection ever enters the enclaves under those conditions. The law also covers the authorisation to conduct strip searches by law enforcement agencies, albeit they have been told to pay ‘special attention’ to particularly vulnerable categories of persons (minors, pregnant women or the elderly). Along with 80 other organisations and individual judges, Alarm Phone strongly condemns these practices and the law on which it is based and demands an immediate halt to hot deportations.

On 10 December, 33 travellers, who alerted AP after they had reached Melilla by boat, were transferred to the local CETI. The situation in the CETIs is still highly precarious, leading to social unrest and suicide attempts . A man who, on August 26 of this year, had tried to jump over the fence to enter the CETI of Jaral in Ceuta, has been convicted to four months in prison for allegedly injuring a guard at the centre.

Carlos Montero Díaz , director of the centre in Melilla since 2012, has been redeployed to become the new director of reception centres on the Canary Islands. The fear is that he has been tasked with the creation of a new Moria. Meanwhile, despite the Supreme Court ruling of July 2020 confirming a registered asylum seeker’s right to move to the mainland, thousands of people are still trapped in the enclaves. The authorities will neither arrange their transfer nor allow them to sort out their own passage to the peninsula. Instead, the Ministry of Interior is now hoping to intensify deportations and to illegally prevent free movement.

Furthermore, there is still no way to practice social distancing or follow basic hygienic measures in the centres. This has led to several outbreaks of Covid-19 , infecting hundreds. As the CETIs are close to collapse, provisional shelters for emergency cases and the most vulnerable travellers have been built in hotels and public spaces. Many travellers, and especially minors, are forced to live on the streets of the enclaves, often seeking shelter in dilapidated buildings. Tents, that were initially put up as a temporary solution to the overcrowded centres for Unaccompanied Minors during the pandemic, have been repeatedly hit by storms (see also previous reports). Although the cities are considering building new centres for the young travellers, the financing of these projects remains unclear. This means the governments of the enclaves are still failing to provide adequate care for the minors.

Racism is also endemic to the classrooms of Ceuta and Melilla. These ‘too have imposed borders that prevent entry’. According to current legislation, every minor residing anywhere in the national territory has the right to a free school place within the state education system. But due to a lack of political will and in spite of multiple recommendations, the enclaves’ administrations are violating the right to education and also the right to equality. They claim that the children do not have a residence permit or can not be registered. A campaign for schooling in the enclaves, which has collected 100,000 signatures, is now initiating legal procedures, reminding the administrations of their responsibility to guarantee access to education for the minors.

We continue to demand justice and dignity for those exercising their right to freedom of movement, and hope that the enclaves become their home or a place of passage, a welcoming stage in their long and complicated migratory journey.

2.4 Nador and the forests

Crossings from Nador were still difficult for sub-Saharan nationals. Although throughout the period covered by this report, every few days a dinghy managed to reach the Spanish mainland from the Nador area, the route still seems to be largely blocked. This is especially true for people from the sub-Saharan communities. In previous years, people from countries south of the Sahara crossed much more frequently from here. Once in a while people from sub-Saharan countries manage to organise a ‘convoy’ and to evade the controls. One such was on 8 November (41 people rescued to Motril) or 29 November (54 travellers rescued to Motril). But as far as we can see, it is, by and large, Moroccan nationals who left from here between October and the end of December.

The seven boats that the Alarm Phone accompanied from the Nador region in that period carried Moroccan nationals. It is currently very hard for sub-Saharan nationals to organise crossing. This is down to several factors. The situation for those that hide out in the forests around Nador is extremely precarious in any winter, but even more so in Covid-19 times. Additionally, the price of a crossings appears to have gone up, perhaps because of the harsher repression of individuals who are arrested during raids and accused of organising journeys.

Apart from the Moroccan ‘harraga‘ (North African travellers taking the clandestine routes), other communities also manage to organise passage via Nador’s beaches. On 24 November, a convoy of 44 passengers was rescued to Motril with, according to the press, primarily travellers of ‘Asian’ nationalities.

Exceptional cases:

- On 1 October, six to eight (number unconfirmed) travellers arrived on the Spanish islets of Chafarinas. Instead of organising their transfer to the Spanish mainland in order to launch a regular asylum procedure, the Spanish military waited for the Moroccan Marine Royale to arrive and take the people back to Morocco. Another push back which denies the right of those concerned to seek international protection in Spain. It should be noted that nevertheless such crossings are sometimes successful. One such occurred on 20 November, when two travellers arrived on a jet-ski on a Spanish islet and were ultimately transferred to Melilla).

- On 30 October, the authorities arrested 74 travellers close to the beach of Kariat Arekmane and brought them to the notorious detention facility in Arekmane, a place we have discussed in previous reports. We couldn’t find further information on their whereabouts.

- On 4 November, four unaccompanied minors died while attempting to reach the port of Nador in order to cross to Melilla. According to the information collected by the Moroccan Human Rights Organisation AMDH Nador, the four minors tried to cross through a drain with a diameter of just 40 centimetres. The duct carries rainwater from the ferry terminal to the sea. The children must have been very young to fit into such a pipe. Three of them died inside the drain, though the details are unknown. The fourth died in the hospital. Just a few weeks later, on 27 November, another young Moroccan national died the same way, while nine of his companions ended up in Nador hospital.

- AMDH Nador took testimony from a traveller, who was among the 56 passengers of a deadly convoy of 26 November. Two mothers with their babies were found dead in their inflatable dinghy by the Moroccan Navy. According to his testimony, before the dinghy was put out to sea, a dispute occurred between the smugglers and members of the auxiliary forces who discovered the boat. The Moroccan forces began throwing stones at the dinghy when they saw that it had already left the shore. In spite of the damaged dhingy, the travellers carried on out into the sea. A dangerous mix of spilt fuel and water caused the death of the two women with their babies. After three hours of sailing, the Moroccan navy intercepted the travellers and brought them back to the port of Béni Ensar. The four dead and the wounded were brought back to the hospital of Nador. Some male travellers were arrested and the rest of the group was eventually released.

The Covid-19 situation remained an issue throughout the period covered in this report. Throughout October in Nador city, at 4pm all shops had to close and from 8pm no one was allowed in the streets. Barriers were installed mid-October at the entries and exits of the city in order to control movement in and out of town – only inhabitants with exceptional exit permits were allowed to pass. While new infections were reaching more than 40 a day in October, the infection rate had dropped by midwinter. On 28 December only 7 new cases were registered within 24 hours in Nador.

The highly precarious situation of travellers in the vicinity is difficult to endure. The AMDH Nador reports on the difficulties in identifying travellers who pass away in the area. On 18 October, the human rights organisation stated that 34 bodies were lying in the morgue of Nador City alone waiting for the court order that would allow them to be buried in dignity. Some of them had been there for several months. Authorities do not establish communications with the families of the deceased, whilst the embassies of the countries concerned do not engage. The AMDH is continually trying to support the identification process, but, even with pictures of the deceased, it is very difficult to speed up procedures. Hence even after death some travellers remain in limbo in the morgue and cannot go to their final resting place.

According to Moroccan press, around 2000 travellers were gathered in the forests surrounding Nador by the end of November, waiting in makeshift camps for their chance to cross from there to Spain. It must be said that it is not clear how the press agency came to this number.

A makeshift camp of travellers, Source: Alarm Phone

A makeshift camp of travellers, Source: Alarm Phone

On 9 November, local AP members reported increased raids in the forests around Nador. Moroccan forces brutally invaded the makeshift camps of travellers and burnt them down. The arrested people were not pushed far away this time. Most of them were released not too far from Nador. Others, however, remained under arrest. The authorities have opened investigations and legal cases against them.

The ashes of a camp after the raids. Source: AMDH

The ashes of a camp after the raids. Source: AMDH

At the end of November, Moroccan forces systematically raided the forest camps, They were especially thorough in the forests of Bolingo and the ‘Carrière’ (quarry). People were caught by surprise and couldn’t rescue their possessions before the camps were burnt down. We have been told of many people with literally nothing anymore. They faced the coldest and roughest part of the winter without even the most rudimentary protection. Survival in the forests was hard enough before the raids. People try to squeeze together, five or six people to one makeshift ‘bunker’, a sort of tent built out of sticks and plastics. Where elsewhere social distancing is a tool to avoid infection, in the forests people bunch together to fight against the cold and sicknesses.

A ‘Bunker’, tent, under construction. Source: Alarm Phone

A ‘Bunker’, tent, under construction. Source: Alarm Phone

In December, the situation for the travellers seemed to have calmed down a bit, although reports show that arbitrary arrests and expulsions, rather than systematic raids, were happening more frequently again. People were usually still released in close proximity to Nador. Some end up arbitrarily in prolonged detention. This happened to a group of 30 travellers who were arrested in the night of 15 December at the beach of Kariat Arekmane close to Nador. They were brought to Arekmane detention centre. So far the AMDH could not find information on their whereabouts.

2.5 Oujda and the Algerian borderzone

As the Alarm Phone team in Oujda reports, the situation of sub-Saharan travellers on the ground remains consistently bad. Most of them still have no opportunity to earn money and are dependent on support. This is partly available, but it is by no means sufficient for all the people who are in need of it. Some are able to go to aid organisations and receive food there, but most have to leave empty-handed. Those who are lucky enough to have neighbours who show solidarity are supported by society, while those who are unlucky have great difficulty paying the rent, electricity and water bills. Many people are homeless and have to struggle on the streets of Oujda. Some of them find support in the church in the city centre. It hosts about 80 people in its premises, although you cannot stay there indefinitely. For some people it is a safer place. They can stay, sleep and eat there.

Meanwhile, push-backs to the border region with Algeria continue. Between 15 October and 5 November, a total of 45 sub-Saharan travellers, including four women and three minors were deported from Nador and Tangier and abandoned in no man’s land. The people were let go in small groups of around ten people. As always, their phones and money were taken from them. 35 made it back to Oujda. We don’t know the whereabout of the remaining 10. They probably crossed the border to Algeria.

In the four days from 15 to 18 November, there were racist persecutions by police forces against Black people who ask for money at a busy roundabout. People have been stationed there for years, asking for support from passers-by. During this operation the police officers tried to chase away the approximately 25 Black people who were there with insults and threats. This verbal violence was aimed only at Black people who were there asking for money and not at the other people present. Of course, after the end of this attack, the people concerned, most of them women, were back at the spot. They have no other option.

Friends of the Alarm Phone team in Oujda who live on the other side of the border in Algeria, report deportations from Algeria to the border with Niger. More details in the following section.

2.6 Algeria

As we highlighted in our previous report, this past summer showed a significant change in migration trends in the western mediterranean region, with vastly more travellers departing from Algeria. There are multiple political and social reasons motivating the Algerian “harragas”.

In 2020, Algeria was the most represented nationality among arrivals in Spain: From January to October, Algerians accounted for 39.5% of all travelers to Spain. Regions of departures include the North West of the country, from the coasts of Oran and Mostaganem heading to Spain, either the Balearics or the mainland. In the East, Annaba is the most important starting point for the journey in the central Mediterranean, towards Sardinia in Italy. But this year has also shown a trend towards diversification of routes from Algeria. In addition to the traditional routes in the West and East of the country, ten provinces count as departure points, including Chlef, Skilda, Aïn Témouchent, Tlemcen, Jijel, Tipaza and El Tarf.

Among the numerous boats leaving Algeria, many are intercepted by the Algerian coastguards. In September, the Algerian Defence Minister declared that between 15 and 25 September, the coast guards intercepted 1200 Algerian nationals, and found ten dead bodies near the coasts of Oran, Mostaganem and Tlemcen. In case of interception, travellers are exposed to severe penalties once back in Algeria. In a 2009 law that aligns Algerian migration policy with the standards of European states, the crime of “illegal exit” from the territory exposes Algerian nationals to a penalty ranging from two to six months in prison and a fine of 20,000 to 60,000 DA. This law shows that the Algerian state thinks that it can ‘control migration’ through repression, rather than by addressing the socio-economic and political aspects that drive the Algerian population out of the country. According to journalist Raoul Ferrat, this leaves the harragas with a growing sense of injustice and only accentuates their desire for exile.

In spite of the increase in controls and interceptions in recent months, many of those who dare to travel the Western Mediterranean route arrive in Europe. There, the reception given by the Spanish authorities became more and more repressive towards the end of 2020. This is in conjunction with active collaboration with Algeria. On 26 December, AP activists were informed of the deportation of 120 Algerian nationals from Madrid to Algiers by charter flight. At the beginning of December, in an agreement widely covered by Algerian media, Algeria officially agreed to take back its nationals who had entered Spain illegally. After Morocco and Mauritania, Algeria is the third country to sign this agreement with Madrid. The Spanish Ministry of Interior announced at the same time the chartering of three boats for an operation to expel people to Algeria. The Interior Ministry cited the “absence of regular transport” because of the closure of borders in response to the Covid-19 pandemic to justify this exceptional operation. It is still unclear when this massive expulsion will take place, but we do know that the price of the operation is close to €200,000 and that it will probably be financed by the European Union’s Asylum-Migration Integration Fund (FAMI).

In recent months, the Alarm Phone has been involved in several cases with departures from Algeria. More commonly though, shift teams and the AP team in Oujda in Morocco (near the Algerian border) are contacted by Algerian nationals looking for their relatives. They are worried after several days without news of their loved ones. AP activists are working on the follow-up of such cases and the best ways to support relatives.

Concerning the situation for sub-Saharan travellers in Algeria, it is known to be extremely difficult. The Algerian authorities are violent and push-backs to the borders are common. Oujda activists and Alarm Phone Sahara have reported and documented deportations from Algeria to the border with Niger. Between 25 October and 26 November, a total of 113 people, including 31 women, were deported from Maghnia and Tlemcen, according to reports from the field. In groups of about 40 people each, they were packed onto buses and brought to Assamaka, a border town in Niger. On this approximately 2500km, 36 hour journey, the people were sometimes not given anything to drink or eat. According to the unofficial agreement between Algeria and Niger of 2014, the deportees are then brought to Agadez to prepare their “voluntary return” with the support of IOM.

Also, in November, AP Sahara reported that at least 1089 people were deported between 12 and 14 November (445 on the 12th and 644 on the 14th) in two unofficial convoys from Algeria. They were dumped in Assamaka. The deported included nationals from Guinea Conakry, Mali, Sierra Leone, Ivory Coast, Burkina Faso, as well as citizens from Liberia, Cameroon, Togo, Ghana, Mauritania, Benin, Nigeria, Guinea Bissau, The Gambia and Ethiopia, and among them many women and minors. According to NGO Human Rights Watch, Algeria systematically engages in arbitrary detention and collective expulsion of Sub-saharan travellers, including children and asylum seekers, without regular procedures. According to humanitarian workers in Algeria and Niger, children are sometimes separated from their families during the raids, and some under ten years are detained and deported.

Sub-saharan African communities are exposed to relentlessness violence by Algerian authorities and live in extremely precarious conditions. Sometimes this leads to tragic events, such as this car accident in southern Algeria on 31 December, where 20 travellers lost their lives.

3 Spanish Migration Policy

It took a year since arrival numbers in the Canaries began to spike for Sanchez, the prime minister, to respond to the human drama that is unfolding on the islands. Unfortunately, the solution proposed by his government is not one that is based on the guarantee of access to international protection through the provision of legal assistance, translators and support. It is based in a politics of repression and control through secret intelligence and diplomatic ties to promote “cooperation for development” with African countries. Its major methodology is the reinforcement of semi-closed encampments in the islands and preventing onward movement to the peninsular. Relocations are limited to those considered “vulnerable”. The message is clear, “arriving in the Canary Islands is not arriving in Europe”.

The Spanish state systemically violates the freedom of movement of thousands of asylum seekers who are resident in the Ceuta and Melilla enclaves. The Spanish state appeals to the fact that that the enclaves are not in the Schengen territory to prevent onward movement. This is a legal nonsense. Article 19 of the Spanish constitution guarantees freedom of residency and movement within the Spanish state irrespective of one’s administrative status. This constitutional breach has been extended to the Canary Islands. As the islands are in the Schengen zone, we can see that the Spanish state is more concerned with preventing Africans from moving than they are by the need to uphold the constitution.

One month ago, any person could leave the Canary, just so long as they had a passport. However, police controls on out-bound passengers who are read as ‘migrants’ because of their ethnicity have been creeping up. It is now practically impossible to leave the islands if you are a migrant. We know the results of these policies from the examples given by the refugee camps in the Greek Islands or the CETIS (Centres for Immigrant Temporary Stay) in Ceuta and Melilla.

The Spanish Home Office continues to militarise the borders of transit countries and the countries of departure. It is worth highlighting that the Spanish state has sent two warships, an offshore patrol boat, a plane, a helicopter, and a submarine to Morocco, Senegal and Mauritania. They will work with the Guardia Civil and Policia Nacional to strengthen border control. In addition, The European Union Agency (Frontex) is going to deploy teams in the Canary Islands to reinforce the Police there. The Prime Minister is also negotiating with Senegal and Frontex to deploy aerial resources on the Atlantic route.

In a radio interview on border control, Marlaska, the Home Secretary, said, “40% of the boats that leave from African countries never arrive in the Canary Islands because they are intercepted in the sea and returned to the African coasts thanks to the collaboration and cooperation of the transit countries”. His boast overlooks issues around whether the transit countries are governed by dictators, respect human rights, or even whether there are people looking for asylum amongst those on the move. From our point of view, we need to know if this approach results in ‘hot deportations’ from the immense Spanish SAR zone. It is an area which is three times bigger than the state and people within it ought to be protected from possible refoulement.

The number of Framework Corporation Agreements with third countries on the readmission of migrants is still multiplying. The latest country to sign one of these agreements is Senegal. In general, Morocco rejects the return of non-nationals. The exception is third countries nationals who enter Europe through Ceuta and Melilla, as the 1992 agreement by which Morocco accepts such returns still applies. At the same time, forced deportations to Mauritania have been reactivated with a Frontex flight in which, out of 21 passengers, only 1 was from Mauritania. There were also 18 people from Senegal and 2 people from Guinea. Spanish law tasks an ombudsman with the responsibility for overseeing deportation flights as part of their “mechanism for the prevention of torture”. They have documented several irregularities in repatriation flights. Citizens’ collectives have also condemned the state’s opacity as well as their practice of abandoning migrants in countries which are alien to them. It is a strategy which leaves people defenceless and without any hope of assistance.

4 Shipwrecks and Missing People

On 30 September, a Moroccan minor was found dead drifting in a boat in front of the coast of the Spanish peninsula, close to Alcaidesa. Apparently he died of hypothermia .

On 1 October, a dead body was retrieved from the sea in the Strait of Gibraltar.

On 2 October, 53 travellers, among them 23 women and 6 children, went missing at sea. The boat had left from Dakhla heading to the Canary islands. AP could not find information on their whereabouts. (Source : AP).

On 2 October, one body was recovered from a boat carrying 33 travellers south of Gran Canaria. Five other passengers were in a critical condition.

On 2 October, as reported by human rights activist, Helena Maleno, from another boat with 49 travellers on board on the Atlantic route, 7 had to be transferred to the hospital in a critical condition. 2 people later died in the hospital.

On 6 October, a body was retrieved from the water off Es Caragol, Mallorca, Spain.

On 6 October, a body was washed ashore at the beach of Guédiawaye, Senegal.

On 9 October, Alarm Phone kept searching in vain for a boat carrying 20 travellers from Laayoune. They remain missing. (Source: AP).

On 10 October, one body was recovered by Algerian forces from a boat that had initially carried 8 travellers from Oran, Algeria. Two others remain missing, 5 of the travellers were rescued.

On 12 October, 2 bodies of Moroccan nationals were retrieved from the sea off Cartagena.

On 16 October, 5 survivors of a 10 day odyssey at sea reported that 12 of their fellow travellers went missing at sea, The boat was eventually rescued off Chlef Province, Algeria.

On 20 October, a traveller died on a boat with 11 passengers that had disembarked from Mauritania heading for the Canary islands. (Source: Helena Maleno).

On 21 October, the Guardia Civil picked up the dead body of a young Moroccan national in a wetsuit on a central beach in Ceuta.

On 21 October, Salvamento Maritimo rescued 10 travellers in a dinghy on their way to the Canary islands, one of them died before the rescue.

On 23 October, the engine of a boat from Mbour/Senegal exploded. It had around 200 passengers on board. Only 51 of them could be rescued.

On 23 October, a body was washed ashore in the municipality of Sidi Lakhdar, 72 km east of Mostaganem state, Algeria.

On 24 October, a young man in a wetsuit was found dead on the beach of La Peña.

On 25 October, a boat that had left from Soumbédioun/ Senegal with around 80 people on board collided with a Senegalese patrol boat. Only 39 travellers were rescued.

On 25 October, a boat with 57 passengers capsized off Dakhla/ Western Sahara. One person drowned. Rescue came quickly enough to save the other travellers.

On 25 October, Salvamento Marítimo rescued three people and recovered one body from a kayak in the Strait of Gibraltar.

On 26 October, 12 Moroccan nationals drowned on their perilous journey to the Canary islands.

On 29 October, we learnt about a tragedy in which probably more than 50 people went missing at sea. The boat had departed from Senegal two weeks previously. 27 survivors were rescued off northern Mauritania.

On 30 October, another major shipwreck occurred off Senegal. A boat carrying 300 passengers that was on its way towards the Canaries capsised off St. Louis. Only 150 people survived. Around 150 drowned, but the information is unconfirmed.

On 31 October, one person died on a boat from Senegal towards Tenerifa. the boat had started with 81 passengers.

On 2 November, 68 people reached the Canary islands safely while one of their comrades lost his life at sea.

On 3 November, Helena Maleno reported that a boat which had left Senegal capsized. Only 27 travellers were rescued to Mame Khaar beach. 92 are assumed to have drowned.

In the beginning of November, four Moroccans drowned who tried to access the port of Nador in order to cross to Melilla through a sewage channel.

On 4 November, a group of 71 travellers from Senegal reached Tenerifa. One of their comrades died on the journey.

On 7 November, 159 people reach El Hierro. One person died in their midst.

On 11 November, a body was recovered off Soumbédioune, Senegal.

On 13 November, 13 travellers from Boumerdes/Algeria drowned, trying to reach Spain on a rubber dinghy.

On November 14, after 10 days at sea, a boat from Nouakchott arrived in Boujdour. 12 people had passed away on the journey. The other 51 passengers were brought to a detention center. (Source: AP Maroc)

On 16 November, the engine of a boat exploded off Cape Verde. The boat had departed with 150 passengers from Senegal and was on its way to the Canary islands. 60 to 80 people went missing during the tragedy.

On 19 November, 10 people were rescued on their way to the Canary islands, one of them died before arrival.

On 22 November, three bodies of young Moroccan nationals were retrieved off Dakhla.

On 24 November, eight travellers died and 28 survived, trying to reach the coast of Lanzarote.

On 24 November, a dead man was recovered from a boat that was rescued by Salvamento Maritimo to the south of Gran Canaria. The boat had initially been carrying 52 people.

On 25 November, 27 people went missing at sea. They had left from Dakhla, among them 8 women and one child. Alarm Phone couldn’t find information on their fate (Source: AP).

On 26 November, two women and two babies were found dead in a boat with 50 people from sub-Saharan countries. They were taken by the Marine Royale to the port of Nador.

On 27 November, a young Moroccan national died in a rainwater channel trying to cross to the port of Nador in order to cross to Mellila .

On 28 November, a Moroccan national was recovered dead from a boat carrying 31 passengers from Sidi Ifni/ Morocco which was intercepted by the Moroccan Marine Royale.

On 2 December, two bodies were recovered on a beach in the north of Melilla.

On 6 December, 13 people capsized off Tan-Tan/ Morocco. 2 bodies were found and 2 people survived. The other 9 remained missing.

On 11 December, four bodies of Algerian ´Harraga‘ from Oran were retrieved from the sea, while seven others remain missing.

On 15 December, two bodies were found by the Moroccan navy off Boujdour.

On 18 December, 7 people are presumed to have drowned though their comrades managed to reach the coast of Almería under their own steam.

On 23 December, 62 people were shipwrecked off Laayoune. Only 43-45 people survived, 17 or 18 went missing. One person died in hospital. (Source: AP)

On 24 December, 39 travellers were rescued off Granada. One of the three passengers who had to be hospitalised died the next day in the hospital.