Carla Höppner, Corinna Zeitz

The cooperation between Spain and Morocco in migration control can be seen as a paragon of policies of externalisation that the EU tries to implement in other regions, too. In 2016/17, despite an increase in militarisation, more people than in the previous years managed to reach Spain from Morocco by sea or by crossing the fences of Ceuta and Melilla. In Morocco, the persecution of transit migrants persists – people are kicked out of their flats, camps are burned by military agents and people are arrested arbitrarily and deported to the south of the country.

On December 12th, 2016, the second regularisation campaign was launched in Morocco. During the first campaign in 2014, 25,000 out of 28,000 applicants were granted Moroccan residence permits. They allow for legal employment but do not protect against repression that sub-Saharan migrants in particular are subjected to. It is possible, that the wave of persecution in early 2017 motivated the departure of many towards Europe. Between January and April 2016, 2,476 people arrived in Spain by sea, while, over the same period of time in 2017, 8,385 arrived. A total of 2,096 sub-Saharan refugees managed to cross the highly militarised fences into Ceuta and Melilla in 2016.

Ceuta and Melilla

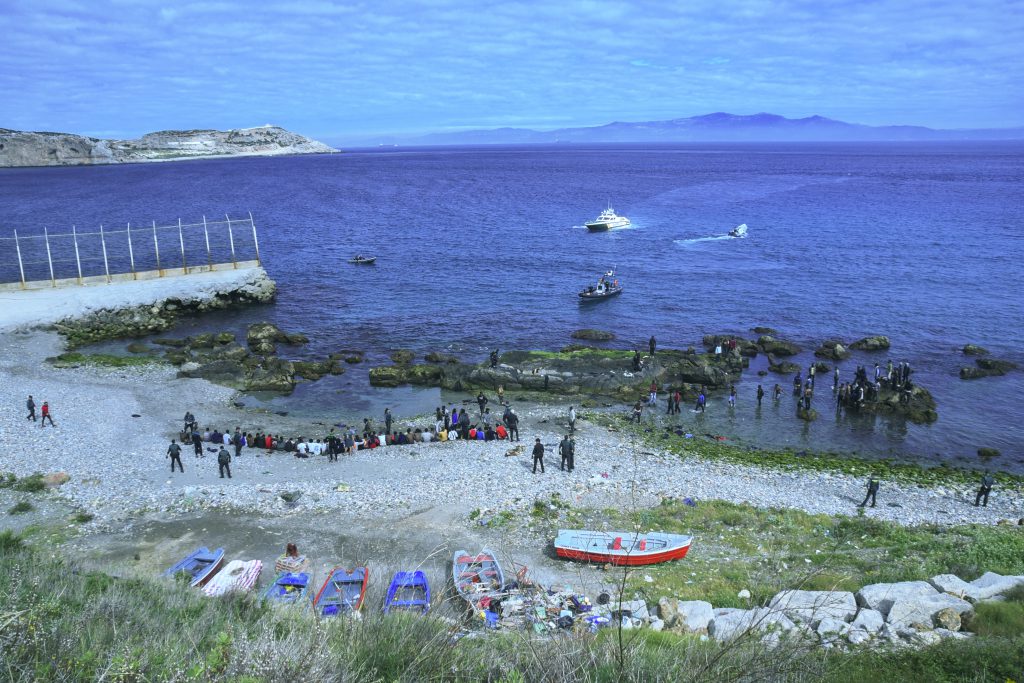

In 2016, despite the high-tech surveillance at the border, 1771 people reached Ceuta by overcoming border fences and their razor-sharp blades. Due to the spectacular collective arrivals of sub-Saharan migrants, also in 2017 Ceuta receives a lot of attention with regards to issues around migration. In February 2017, 842 people managed to reach the enclave of Ceuta through collective organising and strategising, able to bypass the surveillance technologies. Since then, surveillance measures have increased, intended to block border crossings. The Spanish minister of the interior intends to use drones at the border in the future and the Guardia Civil calls for the reinforcement of its forces.

Morocco keeps using issues of border security as political leverage with Spain. When in conflict with the EU, for example following the judgment of the European Court of Justice to exclude the Western Sahara (under Moroccan occupation) from a free trade agreement between the EU and Morocco, open threats of discontinuing border control are made. The Moroccan minister of agriculture announced after the judgment: “Why should we continue playing the watchdog?”

However, just as in other border regions, the EU prefers to cooperate with dictatorships, rather than with those who try to escape from them. On February 20th, 2017, more than 100 people, including a member of the Alarm Phone, attempted to reach Ceuta via the fences. They were unlawfully pushed back after having crossed the border and were subsequently arrested in Morocco. After this “push-back”, the detainees were kept in prison for several months without any legal aid, and afterwards, some were deported to their countries of origin. Nonetheless, the mass crossings into Ceuta via the fences show that the borders can be overcome by migrants when sticking together. On August 1st, 2017, the sub-Saharan communities prevailed again, with 81 crossings via the fences. On August 7th, 2017, 187 people crossed border directly at the border checkpoint by simply “overrunning” it.

In Melilla, only a relatively small number of people (325) made it over the fences in 2016. However, 2,500 Syrians who claimed asylum at the border checkpoint arrived also in the enclave. In 2017, Melilla is also the destination of persecuted members of the Rif movement who fear repression and claim asylum in Spain.

The sea route

Compared to previous years, more people come from Morocco to Spain by sea again. In 2015, 5,302 arrivals were counted, 8,048 in 2016, and up until August 2017 alone, already 8,385. Overall, there are also more north African migrants among the groups of travellers. In 2016, 31 % of all migrants by boat were from Algeria and Morocco, 69% of sub-Saharan origin. In July and August 2016, there were nearly 1000 arrivals along the coast of Andalusia.

On July 14th, 2017, 26 sub-Saharan women and five children reached one of the uninhabited Spanish islands, Isla del Mar. Aware that there had been illegal pushbacks from the Spanish islands close to the Moroccan mainland in the past, they kept shouting “asylum” when approached by the military forces on the island. The Spanish media reported on their resistance so that the group of women finally managed to be granted admission in Melilla/Spain.

Day of Protest on the second anniversary of the ‘Tarajal case’ in Rabat, 6th February 2016. Photo: Alarm Phone

In 2017, in the Strait of Gibraltar, a particularly high number of boat journeys was documented by the Alarm Phone. Our cooperation with the Spanish maritime rescue organisation Salvamento Maritimo (S.M.) varies from case to case. In many situations, the Spanish authorities are highly committed, sends helicopters to search the sea, and rescues many before disembarking them in Spain. Nonetheless, collaborations between S.M. and the Moroccan Marine Royale too often lead to tragic events.

On June 26th, 2016, the Alarm Phone witnessed a deadly interception practice in the Strait of Gibraltar. A greatly distressed caller from Morocco told us that his brother had left early in the morning in direction of Tarifa (Spain) on a boat with eight people. S.M. asked the Moroccan Navy to assist the boat in distress. The Alarm Phone was then able to speak with a passenger on the boat who informed us about the deadly consequences of this collaboration: The rapidly approaching ship of the Marine Royale causeed the migrant boat to capsize and the travellers all fell into the water. The Marine Royale could only retrieve five people alive, a Senegalese women and two men drowned. Their bodies were not recovered. One of them was the brother of the caller. The survivors published a statement together with the Alarm Phone in commemoration of their lost friends. Many of our callers inform us about similar events that make it clear that the Marine Royale, the EU’s cooperation partner, is not a search and rescue organisation but a force to prevent migration.

The problematic cooperation between the S.M. and the Marine Royale also became evident in another Alarm Phone case, on July 11th, 2017 (see ‘Particularly Memorable Cases, in this brochure). In this distress case, the Spanish S.M. assumed that the Marine Royale had already rescued the boat but when the Alarm Phone contacted a person from the boat in order to have the rescue confirmed, we learned that the boat was still in a situation of distress. Our shift team immediately informed the S.M., which subsequently launched another search and was then able to rescue all travellers. This case also demonstrates how handing over the responsibility for rescue to the Moroccan Marine Royale could have easily had fatal consequences.

We have often witnessed these forms of everyday cooperation between Spain or the EU and Morocco. Due to the daily practice of interception by the Marine Royale, the right to asylum and protection is denied to travellers, and interceptions often cause deadly shipwrecks. The ability of the Alarm Phone to form an ear- and mouthpiece for travellers in life-threatening situations at sea continues to be a decisive factor of our work.

Self-organisation

In Morocco, members of the Alarm Phone are active in different parts of the country. They are an important fundament for the work of the Alarm Phone: They raise awareness in the different communities about the absolutely necessary safety measures to take during risky boat crossings and they distribute our phone number in order to prevent deadly catastrophes. The Alarm Phone groups and individuals in the cities of Tangier, Ceuta, Tetouan, Nador, Oujda and Laayoune organise at the grassroot level, they observe and report on the situation on the ground, and they organise political actions.

The Alarm Phone group in Oujda, for example, took part in organising a caravan from Oujda to Figuig on June 25th, 2017. In solidarity with 50 Syrians blocked in the border region between Morocco and Algeria, the caravan travelled 400km. The 200 participants of the caravan encountered another 350 protesters living in Figuig. After a pushback by the Moroccan authorities, the 50 Syrian refugees had been detained in the no-man’s land between the Moroccan and Algerian border for nearly two months. In June 2017, 28 of these people were finally able to enter Morocco. The others went into hiding shortly before.

The Alarm Phone group Ceuta was founded on April 23rd, 2016 after a successful protest campaign against the pushbacks that happen there regularly. By boat, 100 migrants had reached small rocks that lie in close proximity of Ceuta. In order to not be illegally returned to Morocco by the Spanish Guardia Civil, they protested, loudly claiming their rights. Subsequently, activists who lived in Ceuta exerted public and political pressure on the authorities and as a consequence, all 119 people were admitted to Ceuta. After this joint exercise of resistance, the travellers made use of their right to claim asylum on EU territory.

Movements

On February 6th, 2014, the Guardia Civil attacked a large group of migrants that wanted to reach Ceuta by swimming. In the course of events, at least 14 people were killed. The 6th of February has been established as a day of protest. On February 6th, 2016, 400 angry protesters gathered in front of the Spanish embassy in Rabat under the slogan “Stop the war on migrants!”, in order to demonstrate against the murderous border policies of the EU. It was the first time that sub-Saharan migrants from all over Morocco gathered at this scale in order to publicly raise their voices for a changes in EU border policies. Some of them had personally experienced and survived the 6th of February 2014 in Tarajal. Migrants and groups in solidarity protested in Ceuta, Melilla, Madrid, Barcelona, Strasbourg, Berlin, Rom, Genoa and Idomeni on the same day.

In 2017, the demonstration in commemoration of the deaths of Tarajal in Ceuta took place for the third time. This year, the transnational protest was joined by organisations situated in different African countries. A support network for people in the desert areas joined the commemoration in Niamey (Niger). In Edea (Cameroun) there was a demonstration, responding to the callout of Voix des Migrants. Shortly before, in January 2017, the Spanish judiciary had announced the decision to re-open the previously closed proceedings against the agents of the Guardia Civil who were responsible for the deaths of the 6th of February 2014. In Europe, the largest demonstration against EU migration policies took place in Barcelona on February 18th, 2017. Up to 300,000 participants took to the streets, advocating for the admission of more refugees, safe escape routes and the freedom of movement.

All these protest campaigns show that civil societies in many different countries work together in solidarity to scandalise the murderous isolation of the EU and to stand up for social justice. We demand safe migration routes for all and point out to those politically responsible that migration will continue in spite of continuous investments into surveillance, militarisation and isolation. Morocco is the EU border that has been militarised for the longest period of time. Nonetheless, people continue to claim and enact their right to freedom of movement. Whether in Morocco, Cameroun or Spain: It is about social rights for people, no matter where they live.

[This text is part of the recently published Alarm Phone brochure “In solidarity with migrants at sea!]

Numbers and statistics were taken from:

APDHA 2016: Balance Migratorio Frontera Sur 2016. URL: https://apdha.org/media/Balance-migratorio-16-web.pdf und IOM 2017: URL: https://missingmigrants.iom.int/mediterranean

Further literature:

Voices of the borders – Voix des frontieres 2016. URL: https://beatingborders.files.wordpress.com/2013/07/brochure_voicesfromtheborder_voixdesfrontieres_2016.pdf

“The worst thing is when you have the Marine Royale in front of you […] They even come into Spanish waters in order to bring us back to Morocco […]. And when they come in order to take us, the water causes waves in front of their big boat. It can happen that we capsize with the rubber dingy. That is dangerous, […] if you don’t have a life vest or no life ring, you will die. Because they won’t protect you, they won’t intervene. The people are very scared in that moment, when the big boat of the Marine Royale comes. We had such cases: people who fell into the water in plain view of the Moroccan navy. So often people come back from the water and say that one person is missing, that this person fell into the water when the navy came to intercept them.” (Interview with Fadel Fadiga from February 11, 2016, Tangier).