HM Coastguard appears to have violated own standard operating procedure to orchestrate ‘drift-back’ of migrant dinghy

One year ago it was announced Border Force would not forcibly ‘push-back’ anyone crossing the Channel. However, on 2 January 2023 HM Coastguard officers organised for people to be returned to France from UK waters through subtler means; allowing a dinghy to drift back when they thought they could get away with it.

Records obtained from the Maritime and Coastguard Agency by Alarm Phone’s Channel Group show Dover Coastguard and Border Force deliberately refused to assist an unseaworthy, overcrowded and broken-down dinghy in UK waters. Instead, they watched while the people were pushed by the wind and tide back into the French Search and Rescue Region (SRR), where there was no French vessel to assist them. Less than one month prior four people lost their lives, and an unconfirmed number are still missing at sea, when another dinghy sank in UK waters in close proximity to a fishing trawler.

In this report we break down how this ‘drift-back’ was organised and how HM Coastguard appears to have violated its own Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) in the process. Questions remain about whether the work of this life-saving agency has become prejudiced by the government’s anti-migrant rhetoric and instrumentalised for the purpose of border policing.

Summary of key events on the 2nd January 2023:

- A migrant dinghy, previously escorted by a French vessel, entered the UK SRR despite ongoing engine trouble;

- The UK Border Force vessel TYPHOON was on-scene and reported they were ‘happy to undertake rescue’. However, Dover Coastguard told them to wait for another UK asset;

- Dover Coastguard was aware that the dinghy, with a broken-down motor, was drifting back towards French waters and that the French vessel had left;

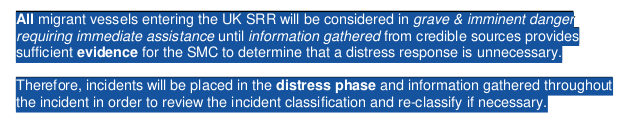

- HM Coastguard’s SOP stated all migrant boats should be considered ‘distress’ situations requiring immediate assistance when entering UK waters;

- Dover Coastguard did not upgrade the incident from ‘alert’ to ‘distress’. Instead it told TYPHOON to ‘STANDBY’ and called the French Coastguard to request the return of the French vessel;

- The wind and tide pushed the dinghy back into French waters where the people restarted the motor and struggled for several more hours to reach UK waters again;

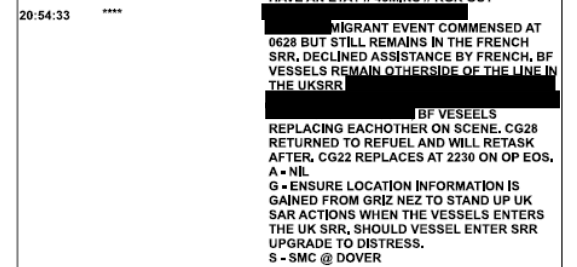

- After the ‘drift-back’, Dover Coastguard stated ‘SHOULD VESSEL ENTER SRR UPGRADE TO DISTRESS’ and kept Border Force vessels at the line to rescue immediately if the dinghy crossed a second time;

- The travellers never managed to cross the line again and were eventually rescued by the French vessel and taken to the port of Calais.

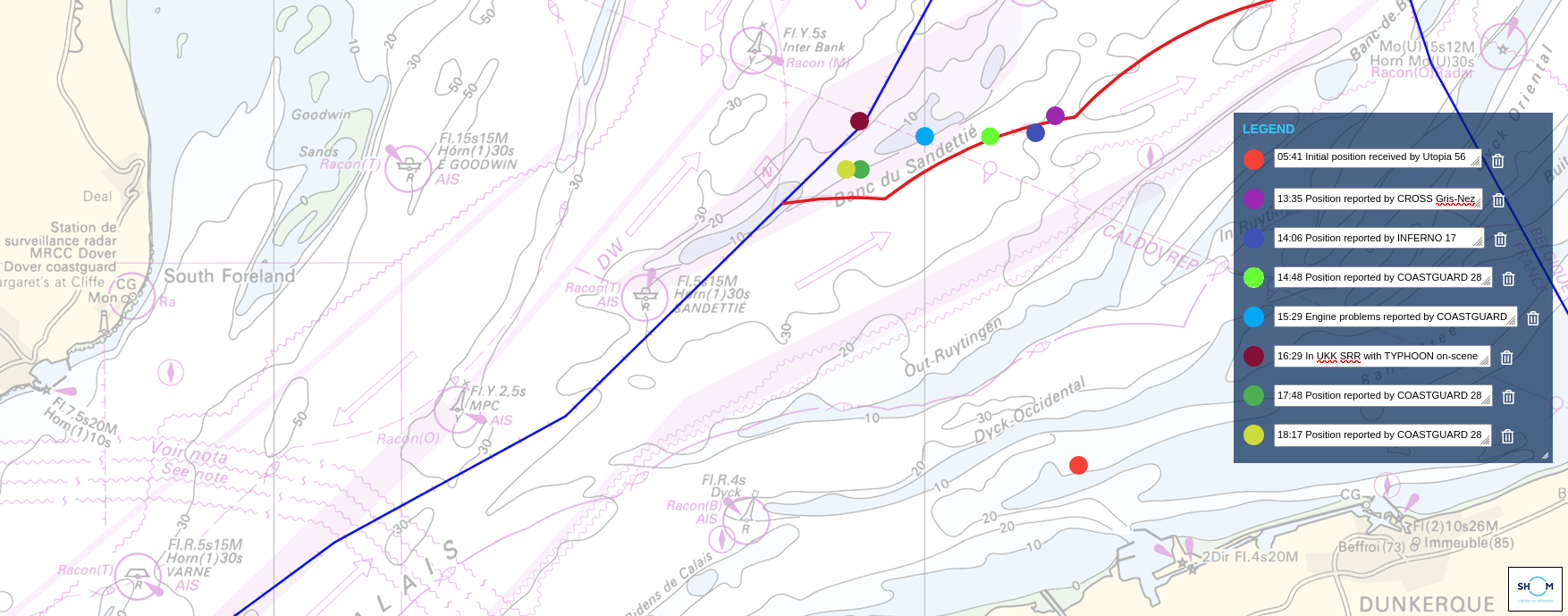

Reported positions of the dinghy throughout its journey and drift-back on 2 January. Map created with data.shom.fr.

The Journey Begins

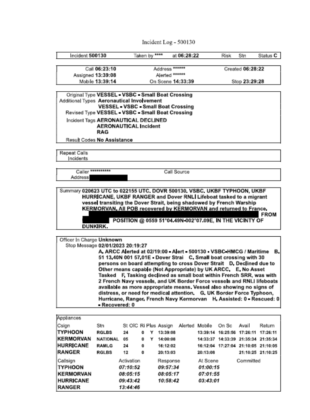

In the early morning of 2 January 2023 Alarm Phone was informed by our partner association Utopia 56 of seven different calls for assistance which they had received from people at sea travelling to the UK. One of these was from someone on board a dinghy, named ‘ECHO’ in HM Coastguard’s log from incident 500130, who shared their location approximately four nautical miles north of Grand-Fort-Philippe. This position was immediately relayed by Utopia 56 to both the French and British Coastguards via an email at 05:51UTC which included the statement: ‘the situation meets the criteria required under SAR 1979 for declaring a “Distress Phase” situation’.

After the initial contact, neither Alarm Phone nor Utopia 56 were able to reach the people in this dinghy again. From HM Coastguard’s incident log it appears ‘ECHO’ was not immediately located, and six hours later, at 12:49, the French Coastguard at Gris-Nez reported it had no updates on the dinghy’s position.

Around an hour later, at 13:35, Gris-Nez reported to Dover Coastguard that a migrant dinghy had been spotted 10 nautical miles north of the position from the morning. The French Custom’s cutter KERMORVAN was sent to find the boat, and Dover Coastguard tasked Royal Navy Wildcat helicopter INFERNO 17 to proceed to the location and get a visual. Ten minutes later Dover Coastguard began organising for a rescue, tasking Border Force vessel TYPHOON to proceed towards the Sandettie Light Vessel where the inflatable dinghy was anticipated to cross into the UK SRR.

At 14:00 KERMORVAN arrived to the dinghy and began tracking it as it continued towards the UK. Minutes later, INFERNO 17 called up with a visual and reported that the people would be at the line of the UK SRR in 30 minutes to an hour. Border Force vessel TYPHOON acknowledged the information and moved to intercept.

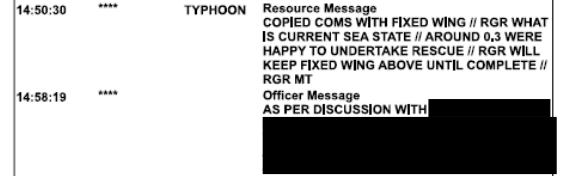

At 14:48, the fixed-wing spotter plane COASTGUARD 28 also spotted the dinghy and reported the people were travelling towards the UK at a speed of three knots. Minutes later TYPHOON acknowledged the update and stated ‘WERE [sic] HAPPY TO UNDERTAKE RESCUE’. A redacted ‘Officer message’ is recorded in Dover Coastguard’s log not ten minutes later. We cannot know the content of this discussion, nor the identity of the discussants, but it may have determined the fact TYPHOON would never perform their rescue.

At 15:29 COASTGUARD 28 reported that the dinghy was ‘DEAD IN THE WATER’, but then that the people managed to restart their engine and were continuing. Around a quarter of an hour later, the airplane put them at 1.15 nautical miles from UK waters, 20 minutes away at its speed of three knots.

For reasons not explained in the log, before ‘ECHO’ crossed the line into the UK SRR Dover Coastguard appears to have changed the organisation of the rescue. At 16:12 HURRICANE, another Border Force boat, was sent from the Port of Dover to meet with TYPHOON. Tasking instructions for the two vessels were updated at 16:28: HURRICANE was to ‘LOCATE AND RECOVER ALL PERSONS TO PLACE OF SAFETY’ whilst TYPHOON would only ‘PROVIDE SAFETY COVER AND SHADOW VESSEL PROGRESS IN UK SRR’.

Why was HURRICANE tasked with the rescue when it was around an hour from the dinghy imminently entering the UK SRR whilst TYPHOON was already on-scene and ‘happy to undertake rescue’? There is a redacted message from TYPHOON from 16:14 which may shed more light on this question. One possible explanation is that TYPHOON had been active since 07:10 that morning and the crew may potentially have been required to work overtime to perform the rescue, whereas HURRICANE had begun their day at 09:43. While we cannot know why the decision for HURRICANE to perform the rescue was taken, we know that it had drastic consequences for the people on-board the dinghy.

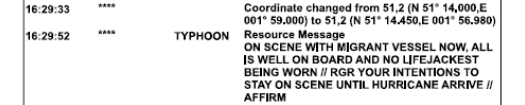

Across the line: the lies and cover up begin

At 16:29 TYPHOON reported to Dover Coastguard that it was ‘ON-SCENE WITH MIGRANT VESSEL’ at position 51° 14.45’N, 001° 56.98’E, inside the UK’s SRR. They communicated ‘ALL IS WELL ON BOARD AND NO LIFEJACKEST [sic] BEING WORN’. This statement not only appears untrue—how could ‘all be well’ for people not wearing lifejackets inside an overcrowded rubber dinghy with engine trouble in the middle of the world’s busiest shipping lane?—but reveals the callousness with which the UK Border Force and Coastguard regard the people in these boats whom they have a duty to assist. TYPHOON, rather than assist the people directly, followed Dover Coastguard’s instructions to wait until HURRICANE arrived.

An officer on-board KERMORVAN described communicating with TYPHOON, and being told ‘they would rescue the people on the dinghy‘. The French vessel, assuming the people in British waters would quickly be rescued and taken to a place of safety in the UK, left the scene with the approval of Gris-Nez. In another article, the same officer describes later being told by TYPHOON that they could not take the people on-board because there was no room; a statement which the log proves was false as they had room but were waiting for HURRICANE.

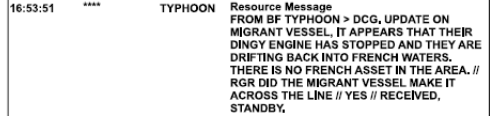

At 16:53 TYPHOON called Dover Coastguard to inform them that the dinghy’s engine had broken-down again. The Border Force boat said the people are ‘DRIFTING BACK INTO FRENCH WATERS’ where ‘THERE IS NO FRENCH ASSET IN THE AREA’, and that the dinghy indeed had made it into the UK SRR. These facts directly contradict statements about the incident made by the Ministry of Defense, which ‘dispute that the dinghy entered UK waters’, and other ‘British sources’ which stated ‘the boat never entered UK waters and that there was not a risk to life as it was being shadowed by a French coastguard boat, the Kermorvan’.

The ‘Drift-back’

At this point Dover Coastguard knew there was an adrift and overcrowded dinghy with people on-board who had been at sea for more than 10 hours. Not only was the safety of the people on board this dinghy its responsibility, it also had an asset already on-scene ‘happy to undertake rescue’. As we will see in the next section, at this time, the incident should have been declared to be in the ‘distress phase’ and TYPHOON instructed to effect the rescue. Under the international law of the sea there was nothing legally preventing TYPHOON from rescuing the people, even if the vessel would have re-entered French waters. Instead Dover Coastguard instructed TYPHOON to stand-by and watch as the dinghy drifted back towards France.

Within three minutes Dover Coastguard had called Gris-Nez to ask them to send KERMORVAN back to the scene. According to the customs officer on-board it would be another hour of searching in the dark (sunset was at 15:59 that day) until they were able to find the dinghy again around 18:00.

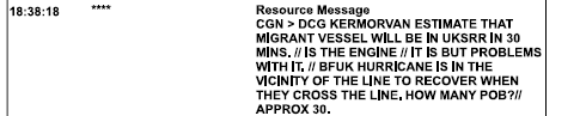

Despite being refused assistance in UK waters and abandoned to the sea for the last hour, the 38 people did not give up. They fought against their engine trouble, the wind and the tides, determined to continue their journey and reach the UK. At 18:38 Dover Coastguard was informed by Gris-Nez that the boat would be back in UK SRR about 30 minutes later, but that there were still problems with the engine. Dover Coastguard replied ‘HURRICANE IS IN THE VICINITY OF THE LINE TO RECOVER WHEN THEY CROSS THE LINE’.

The people would never make it. Unable to continue any longer they were rescued by 20:00 according to a statement from the KERMORVAN’s officer.

‘the people on the dinghy were exhausted and afraid and frozen. We took them onboard and gave them blankets, food and hot drinks. Everyone survived. The UK didn’t push them back but let them drift.‘

The people arrived in the port of Calais two hours later where they were met by the border police and fire department, and volunteers from Utopia 56 who helped to raise the alarm more than 15 hours earlier. According to Utopia 56, everyone from the boat was soaking wet and cold and at least one person was hospitalised with hypothermia.

Violating Standard Operating Procedure

Before the log ends there is a partially redacted entry which raises urgent questions about Dover Coastguard’s coordination for this incident. When the dinghy entered UK SRR Dover Coastguard had categorised incident ‘ECHO’ as being an ‘alert phase’ situation ‘where apprehension exists as to the safety of an aircraft or marine vessel, and of the person on-board’. However, at 20:54 the log states: ‘SHOULD VESSEL ENTER [UK] SRR UPGRADE TO DISTRESS’.

Nothing was reported to have substantially changed about the dinghy’s condition in the hours between when it was inside the UK SRR and when this statement was made that it should be upgraded to distress if it would enter the UK SRR again. The weather had not drastically changed, the same number of people were on-board, there was the same intermittent engine trouble, KERMORVAN was close-by on both occasions and visibility was restricted due to darkness. With no indication of what may have been different to warrant an upgrade later in the day, should the incident have been considered to be in the distress phase and immediately been rescued by TYPHOON earlier in the day? The answer, judging from HM Coastguard’s own SOP, appears to be ‘YES’.

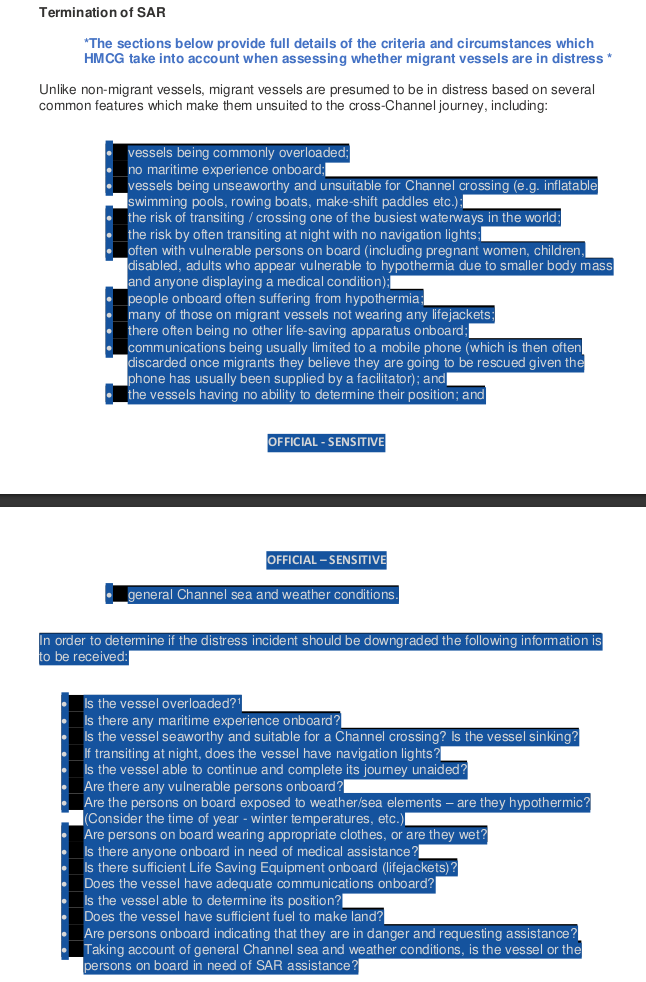

In the 2023 version of the Coastguard’s SOP for ‘Incidents Involving Small Boat Crossings’ obtained under a Freedom of Information (FOI) request, and seen for this report, crucial information on how such incidents should be handled has been redacted. However, in 2021 the MCA released a previous version of their SOP in which the redactions were not done properly. Although the document is covered in black boxes the PDF file was not purged of its underlying ‘invisible’ font created by Optical Character Recognition. Highlighting those supposedly redacted sections allows them to be easily read and important details revealed.

On page one the SOP states that ‘All migrant vessels entering the UK SRR will be considered in grave & imminent danger requiring immediate assistance‘ (emphasis in original).

This insistence on treating all migrant vessels as distress incidents, ‘likely to require immediate assistance’, is repeated again on page three, along with the directive that HM Coastguard must ‘retain coordination of the incident until migrants reach a place of safety’. Based on this we can assume HM Coastguard should have automatically declared ‘ECHO’ to be in the ‘distress phase’ and rescued by TYPHOON when entering UK SRR the first time. However, there is also scope in the SOP for ‘downgrading’ an incident from the distress phase, and page five lists criteria which the SAR mission coordinator (SMC) must satisfy to do so.

However, there is also scope in the SOP for ‘downgrading’ an incident from the distress phase, and page five lists criteria which the SAR mission coordinator (SMC) must satisfy to do so.

Information in HM Coastguard’s log from incident 500130 shows that ‘ECHO’ failed to satisfy essentially every one of these criteria in order to be downgraded from the distress phase after reaching the UK SRR:

- There were 38 people in a small rubber inflatable dinghy.

- No maritime experience was confirmed, nor would there be reason to assume any.

- The rubber dinghies used for these journeys are not seaworthy and often break apart, leading to deaths. Their engines are under-powered and poor quality.

- There were no navigational lights on the dinghy. KERMORVAN reported difficulty seeing it with search lights at a distance of 200 metres.

- The vessel was obviously having difficulty continuing its journey and would clearly not be able to complete it.

- 14 of the people on-board were deemed to be women, children or babies.

- Everyone on-board was exposed to the elements in the middle of winter. One person was later hospitalised with hypothermia.

- Everyone’s clothes were wet and unlikely to be ‘appropriate’ for taking to sea.

- Whether those on board were in need of medical assistance could not be known simply from aerial surveillance without proper individual assessments.

- There was insufficient Life Saving Equipment on-board, with TYPHOON reporting ‘no lifejackets being worn’ and COASTGUARD 28 reporting many people without one. No other life rafts, position indicating beacons, flares, etc. were present.

- Given the vessel’s incorrect due north course from the morning, it is doubtful it would have been able to to determine its position or proper course for a crossing to the UK.

- The fact that there was an unknown amount of fuel, engine trouble and difficulty making way all point to the conclusion that the dinghy would not have been able to make it to land.

Dover Coastguard might argue that the responses to the final two questions regarding whether people on-board indicate they are in danger and the ‘general Channel sea and weather conditions’ may have been favourable to downgrading the incident in this case. However, this implies the people should nevertheless have immediately been rescued had they requested assistance from TYPHOON. We do not know from Coastguard logs if this was the case, nor can we be confident the Coastguard would have then ordered the rescue if Border Force reported the travellers asking for help.

HM Coastguard as Border Police

‘Drift-back’ tactics are regularly used by so-called Coastguards against migrant boats in other regions, especially the Aegean. Delegating the violence of forcing people back across the border to the sea and the wind provides perpetrators with a modicum of deniability compared to naked push- or pull-backs.

However, for all the similarities that exist between the Channel and the Aegean or Mediterranean contexts, the behaviour of the Coastguards remain different, at least for now. Alarm Phone regularly reports how state authorities in southern regions actively attack boats, disable engines and steal fuel, then abandon them to the elements to ensure passengers cannot arrive to Europe. These sorts of attacks by police are exceptional (though do occur) in the Channel where instead most border violence is distributed across the ‘hostile environments’ of the French beaches and British hinterlands.

In the case of ‘ECHO’ it appears Dover Coastguard took advantage of an opportunity created by a sputtering motor and direction of wind and tide to effect the return of a migrant dinghy to France which it could not be seen to do by force. This was not the first time we have seen such calculated non-assistance by the UK search and rescue authority. The practice may have played a role in the deaths of at least 30 people from the 24 November 2021 shipwreck.

The stated purpose of HM Coastguard is ‘to prevent the loss of life on the coast and at sea’. However, the agency has in recent years been swept into the centre of a far-right political storm by the Conservative government’s demonisation and dehumanisation of people who cross the Channel in public discourse and policy. The consequence of this politicisation is that HM Coastguard has begun working hand-in-glove with Border Force (and, until recently, the Royal Navy) to police the UK’s border and coordinate the surveillance and interception of ‘small boats’. In doing so, the agency has become a key player in turning the Channel into an immigration enforcement pen. By intercepting dinghies at sea to prevent autonomous arrivals to the UK and gathering data with the purpose of criminalising those who steer the boats or facilitating potential future deportations of asylum seekers, HM Coastguard demonstrates itself to be a willing actor in the state’s spectacle of control of the so-called ‘migrant invasion’. The incident from 2 January shows us how HM Coastguard is just as happy to embrace tactical inaction to punish and deter people who cross the Channel in unseaworthy dinghies. In each case, the agency’s mission to ‘save lives’ seems to have become subordinated to the political priority of ‘policing the border’.