Content

1.2 Tangier, Ceuta and the Strait of Gibraltar

1.3 North-Eastern Morocco: From Nador to Oujda

2 Shipwrecks and missing people

Introduction

It should be surprising but isn’t, that capitalist countries, within a capitalist world order seek to criminalise the activity of providing, for financial return, a seat in a boat transporting people from point A to point B. It seems hard to locate the crime in such an activity, even when point A is in Africa and point B in Europe. The fact that the authorities who have placed themselves in charge of the places of arrival wish to prevent the entry of the vast majority of the people who wish to make the journey is scarcely relevant to the legality of helping somebody to leave. People are, after all, leaving from a different and autonomous jurisdiction to the one they arrive in. Nevertheless, as our report clearly shows, helping people to leave has come to be seen as a terrible crime.

This is not to say that there are no crimes involved here. If I sell you a seat on a boat that is patently unseaworthy, fail to provide you with adequate safety or navigation equipment, or simply do not lay enough fuel down for the journey, I may well be guilty of recklessly endangering your life. No doubt there are also international maritime conventions that lay down minimum standards that ship owners and ship captains must meet. It is true that, as we have previously reported, once in the Spanish state, individuals deemed to have been responsible for the deadly journeys are facing murder and manslaughter charges. It is also true that these convictions seem dubious and vindictive. It is also the case that the European authorities, including the Spanish state, have a somewhat threadbare commitment to international maritime conventions, at least as they apply to people on the back route to Europe. The Spanish Search and Rescue Authority is perhaps the only remaining authority at the EU’s southern border which has anything that even resembles a commitment to international SAR conventions. Nevertheless, as we found when people were stranded on the islet, Isla del Congreso, or had entered Peñon de Vélez and the state’s practices at the fences of their North African enclaves, the Spanish state is happy to ignore international law at least as it pertains to your right to claim asylum.

It is clear that the Spanish state’s desire to prosecute people for the crimes that are associated with irregular migration is not coming from a deep commitment to the rule of law. It springs from a desire to restrict and control people’s mobility. That desire is an authoritarian desire. It has long been a hallmark of authoritarian states to pass legislation criminalising irregular exit from a territory. Now, although neither Morocco nor Algeria are bastions of freedom, the ratcheting up of pressure on those who attempt to leave and those who facilitate exit is being done in collaboration with European, particularly the French and Spanish, governments. The aim here is primarily to prevent the mobility of people from Africa, whether or not that person comes from North or South of the Sahara, because European governments do not want Africans in Europe. To the extent that we are not surprised by the criminalisation of people from Africa who attempt to leave the continent of their birth it is because we have swallowed the racist logic of the European powers and their (junior) partners in African parliaments.

It was Arendt who, in The Origins of Totalitarianism, observed that it is easier to leave a state than to enter another one. She was drawing attention to the fact that being physically present within a territory is not sufficient for you to be legally recognised in that territory. The problem, as Arendt saw it, is that somebody without legal standing anywhere in the world is a non-person. For Arendt, it is not because you are a person that you have rights, it is that only when you have rights are you a person. We don’t have to follow Arendt to the end of her metaphysics to recognise, along with her, that anyone who is excluded from legal protection is also cast out of the human community. If you have no legal standing, you are at risk of the most extreme violence. You don’t count and the powerful can do with you as they wish. That is why people on the move are subject to such atrocious physical and, particularly if you are a woman, sexual violence and, as we show in this report, criminalised.

That criminalisation takes concrete form in the outrageous sentences imposed, after a mockery of a legal process, on those accused of “people smuggling”. But that is just the visible manifestation of a deeper politics of rejection. The racist logic that governs our world will, if you are African, only acknowledge your limited legal standing on condition of your staying in place. If you dare to challenge that logic by taking your future into your own hands and exercising your right to move, you will lose what little legal standing you had. You will have already been criminalised. But we stand in solidarity with those who make that choice and take that risk. We know, as Elie Wiesel reminds us, that no human being is illegal. We will build a world founded on that fact.

1 News from the regions

1.1 Atlantic Route

Situation at sea

“I never stop doing awareness raising with migrants about the Canary Route, the most deadly route towards Spain. Since August, many boats have disappeared, hundreds of migrants between Dakhla, Laayoune, Tarfaya, Guelmim and Tan Tan are still missing. Their families and loved ones do not stop calling us to ask for news, always hoping for a miracle like the one which occured recently when a boat was found after five days at sea.”

This statement from A, an Alarm Phone activist in Laayoune, sums up the situation in the Atlantic. While relatively few boats left for the Canary Islands in June, dozens of boats have started their journey each week since August. The official count is now at 16,827 arrivals (as of 31 October), which is about a third more than in the same period of 2020.

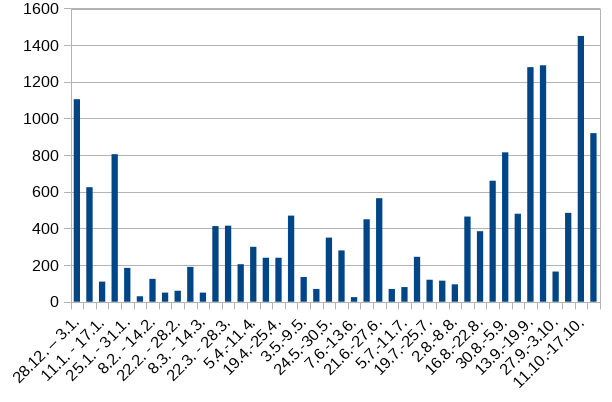

GRAPH: Arrivals in 2021

Source: own representation, based on UNHCR data

We mourn for all those travellers we tried to support across days and nights during these late summer months and who did not make it. We mourn the 23 people who left Boujdour on 10/11 July, 19 sub-Saharan and four Moroccan travellers, who disappeared without trace. Another boat with Moroccan and sub-Saharan passengers, 47 in total, vanished after having left Dakhla on 28 July. We will not forget them. We cry for the 54 people, including 11 women and 3 children who left Laayoune on 3/4 August. We raised an alert about other departures from Laayoune which never arrived (for example, 53 people who left on 13th of August, 58 people who left on 26 August) and yet more from the south west of Morocco, i.e. from Tan Tan and Guelmim, (e.g. 42 people who left on 27 August). The list, even of AP cases, is much longer.

Sometimes the tragedies have a more concrete aspect. There have been several larger shipwrecks among the boats to which we alerted the authorities. 11 people died in late August on the way from Tan Tan to the Canaries. More than 50 perished (Helena Maleno puts the number of dead at 57) in a boat that left Dakhla on 24 September. The other two big shipwrecks in this period left 42 people dead from a boat with 52 travellers which left Dakhla in early August and a boat with 86 travellers that went down leaving no survivors in early September. Miraculously, in the second week of August, 32 out of 46 people managed to survive 14 days adrift and 24 out of 38 travellers survived for 19 days before being rescued far south of Gran Canaria.

Some of the people, who drowned in the big shipwreck with 86 travellers. Source: Social Media screenshot by AP Maroc

Some of the people, who drowned in the big shipwreck with 86 travellers. Source: Social Media screenshot by AP Maroc

When it comes to departures further in the South, interceptions are frequent in Mauritania. In Senegal, there have not been many recent interceptions. 175 people were rescued who were ripped off and abandoned on an island by some travel agents. The local Alarm Phone team reports that the last big interceptions took place at the end of July. There seem to be less boats leaving from Senegal. This is in part due to the sheer length of the journey and the slim chances of survival. Many of the boats that did leave Senegal in the past months went astray and ended up in Mauritania.

Criminalisation at sea

Instead of doing everything within their power to stop this dying at sea, state agencies have increased the repression and criminalisation of travellers as well as travel agents (“travel agent” is the term used by people on the move for the people who are paid to organise the journeys). As Alarm Phone, we fully support the demand for more rescue assets, more staff, more financial ressources and are thus in solidarity with the struggles of the CGT (Confederación General del Trabajo) Salvamento, the largest union of workers of Spanish search and rescue organisation, Sasemar. We are infuriated that European states, the EU and Frontex allocate millions every year to criminalise, punish, deport and torture people on the move instead of properly equipping SAR actors.

In the past months, the Moroccan state has managed to intercept more and more travellers leaving from Western Sahara/the south of Morocco. Several articles in the Moroccan newspaper Yabiladi in the second and third week of October show that the area around Laayoune is particularly targeted. At times there have been several interceptions per day. Hundreds of travellers have been arrested. Further South in Western Sahara, in Dakhla, in late September, the authorities arrested several members of a “trafficking network”. One of those arrested was a policeman, but, since departures in this area are very much dependent on bribery, this comes as no surprise.

The Alarm Phone members in Laayoune describe how criminalisation affects travellers:

“When a boat is intercepted, the police take the phones of different people. The police or gendarmerie then always arrest three to five people and accuse them of having organised the journey – without the slightest proof. They are taken to the prosecutor, an arrest warrant is issued, then an investigation and then they are sentenced and imprisoned. When travel agents are arrested, they risk prison sentences from five to ten or even up to 20 years. These processes are completely arbitrary, without any [defence] lawyers present. Sometimes the accused sign a transcript without even knowing its content, because it’s in Arabic. Officially, there should be a translator present. But none of this is respected. Migrants are not given any rights.”

Furthermore, when it comes to sub-Saharans on the move, very high sentences are not the exclusive provenance of travel agents. They are a general tool of repression. For example a young Ivorian boy was sentenced to 15 years of prison because he menaced a Guinean travel agent after the latter had stolen a sum of money. The local Alarm Phone team puts this harsh repression down to the recent change of the local head of General Intelligence. A change which has resulted in more and more Sub-Saharan travel agents being tracked down.

In Mauritania, the situation is similar, according to the local Alarm Phone team:

“The prison sentences for travel agents is usually six years, minimum five years. But since there is corruption everywhere, the travel agents can just pay a bribe and are then deported to their country of origin instead of going to prison. When it comes to their clients, they are also deported if the boat gets intercepted. If you want to visit somebody in prison, you have to have the same family name as the prisoner, that’s why it’s very difficult to find out more.”

The Spanish state pursues a similar strategy on the Canary Islands. The prison sentences imposed are very high in cases where people died on the journey (e.g. 17 years of prison for those held responsible for five people dying in a boat journey in 2020).

Situation on Canaries

It is clear that transfers to the mainland have been sped up. This has reduced the reception “crisis”. Because of the pandemic, new irregular arrivals are placed into a mandatory 15-day quarantine prior to their reception in refugee camps. In March 2021, you could expect to wait up to six months to receive the news from the Ministry of Internal Affairs of your onward travel to the mainland. By October 2021, the waiting time decreased to an average of about one month. Although this five month reduction is welcome, it is neither here nor there compared with the overall length of the process anyone who takes the “back route” to Europe has to endure.

People with a passport or an outstanding application for asylum request have the right to travel to the Spanish peninsula by themselves. The Spanish state had attempted to restrict the mobility of irregular arrivals, but a Canarian court ruled that preventing people from moving within the Spanish state was unconstitutional. Unfortunately, if you lack a passport or have not yet had your asylum claim documented, you will be stuck in the Canaries. The time taken to register a claim depends on the island, but people report that it can take up to five months for a claim to be acknowledged.

In addition, the lack of independant legal advice for those who decided to leave the camps is still an issue. Many people have, with the support of the migrant community in the archipelago, relatives or locals, already left the camps. Without proper legal advice, the administrative procedures to leave the islands can be too much for the people concerned. There is often a language barrier and many people are afraid to go into the offices of the bureaucracy by themselves.

Although there have not been reports of random detention and deportation of people stopped in the streets, this may be because people without papers fear walking alone. In general, if you are in such a position, you will go out in a group to reduce the risk in an encounter with the police. The situation is summed up well by Mohammed, not his real name, from Guinea Conakry: “The police in Morocco beat me and now I have neck problems. Some people were lucky and did not encounter police, but all of us fear them. They are abusive and the president lets them do whatever they want, here, in Morocco, and in Guinea”. There are also reports of police racism. The Assembly supporting migrants in Tenerife protested one such incident on 26 October. The police had stopped and interrogated a group of young people simply because three black people were out with two white people.

Refugee camps have seen a reduction in both capacity and population as little by little long-term reception centres and facilities have opened. These long-term reception centres are meant to build on “El Plan Canarias”, which was itself developed as a temporary and rapid response to the arrivals in 2020 . According to the authorities, the refugee camps were meant as a temporary installation for 2021. These new reception centres are usually warehouses, buildings, houses or flats managed by large NGOs. They tend to be located in cities or in villages near airports. On an average they have a capacity of 100-150 people. Testimonies from the people held in these new facilities are largely positive. They are less stressful and a closer approximation to normal life than the camp experience. However, the capacity of such facilities is limited and only increasing very gradually, so it is only the most vulnerable people who have had the chance to escape the camps. It would be good to see this trend continuing and to be able to celebrate the closure of the refugee camps by 2022. Nevertheless we cannot forget that the whole system is abnormal, alien and inhuman. There is no need to punish people for seeking a life in Europe. There is no need either for refugee camps or for long-term reception centres. Instead, regardless of the colour of your skin or the country of your birth, you should be free to work, love and live anywhere you wish.

Moussa, also not his real name, from Guinea-Conakry, who remained at a camp for two months put it eloquently when he said that

“I imagined that the arrival at a new continent would be hard, but you don´t realise until you are there. It surprised me the amount of quarantines I had to do, because at the camp we are a lot of people and a positive case means many people will be in quarantine. What nobody told me is that the trip does not finish when you arrive on the shore. The travel within West Africa by feet, bus, car, and then the boat, is more physical, more risky. When I reached the Spanish coast everything changed, and now I´m in the journey of uncertainty and papers. I don´t fear for my life anymore, but now my struggle is mental… uncertainty makes anyone go crazy.”

But where there is repression there is resistance. The Alarm Phone is just one small part of a vast network of projects and individuals working to dismantle fortress Europe. Ishmael, not his real name, a young man from Senegal brings this out well:

“I feel blessed by those people who helped me. Institutions and governments are the same, they talk, they do nothing. They criminalised us for doing something they can comfortably do, move […]. I felt racism in Morocco and also in Spain, but there is always people who are kind, and make you feel at home. It means a lot to find kindness when you feel so lost. […] I have a mother in Senegal and now I have a second mother in Canaries, a wonderful women that opened her house and heart for me. I felt lost, now I feel blessed.”

His “mamá española” (Spanish mother) added:

“Some people appear in our lives for some reason and they might leave, but they will always remain in our hearts. Ismael is a young fighter, like many others”.

1.2 Tangier, Ceuta and the Strait of Gibraltar

Because of the intense border security and frequent arrests in the city of Tangier, few attempts are made to cross the strait of Gibraltar. Nevertheless, Alarm Phone members in Tangier report that a number of people are currently serving long sentences for the ‘crime’ of attempting to cross. In addition, lots of families are looking for their daughters and sons. It is often even hard to find out if the missing are in prison or dead. J. from Tangier says:

“On 7 August 2021 we received a call from a family telling us of the disappearance of their son two years ago and that they had just learnt that the he was sentenced to a long prison term in Fès”, the Alarm Phone activist went on to explain, “it is mainly people accused of organising boat crossings who are detained.”

Everyday life is still a big challenge for sub-Saharan people in the north of Morocco. In the neighborhoods of Rahrah, Boubana, Misnana and others, the landlords who rent apartments to sub-Saharan people also direct the local police to their tenants. The consequence is that the police organise raids and arrest the inhabitants. “The same landlords then re-let the same houses to other sub-Saharan people and the procedure repeats itself”. People are not safe in their homes or on the streets. For instance, on 10 September the local police arrested two women and five men – they had just come to do some shopping – in front of an African shop. What happend to them next is unclear.

The people targeted are also very worried about contagion from Covid-19 as, despite the pandemic, police continue to fill buses and expel large numbers of people. K. from Tangier says:

“In Tangier we are experiencing a lot of police repression even with Covid-19, which has new and more dangerous and deadly variants. The authorities continue to deport black people to the south of the country.”

For example on 26 August, 15 men and one woman and her child were arrested. The woman and child were released before the bus forcibly displaced the rest of the group to Marrakech.

In this context fewer and fewer convoys leave Tangier for Spain. This trend dates back to the beginning of the covid pandemic when controls were intensified in the northern border regions of Morocco in particular. As a consequence, most of the people who wish to cross to Europe went towards the south of the country and to Western Sahara. It is easier to find a place in a boat from those regions, but the numerous tragedies on the Atlantic route also show that it is much harder to make the crossing.

AP members remain committed to the cause.

“We believe that raising awareness of security and risks at sea is still very important for the survival of lots of people who plan to leave – whether it happens from Tangier or Western Sahara”.

But AP members in Tangier are exhausted.

“Daily life in Tangier for black people is, because of Covid-19, very difficult and this has practically blocked all our activities and makes it hard to reach out to people on the move.”

One of the major issues for undocumented people is the kingdom of Morocco’s vaccination strategy. It is still difficult to get the vaccination without papers and a residence permit. Not only does this increase your risk from Covid, it also prevents you from acquiring a vaccination certificate. At present, the vaccination certificate is required in almost all bigger stores and for appoinments in many state offices. J. from Tangier tells us that

“in the face of this situation, many people are desperate. Even if it is currently difficult, the AP Tangier team plans to restart activities to better support affected people and raise awareness of the rights of people on the move.”

In the beginning of August, a tragic death happened in Tangier. On 6 August the body of a Senegalese national was found on the beach of Tangier. Y. from Tangier reports that “On 25 August 2021, our brother was buried in the Mujahidine cemetery in Tangier.” Even if fewer sub-Saharan people on the move are living there than before, the districts of Mesnana and Boukhalef are still the strongholds of people who remain in the city waiting for the next crossing. K. from Tangier is convinced that, even in the face of strong repression, people still believe that they will be able to get to Spain.

Alarm Phone was also involved in a few cases around Ceuta, the Spanish exclave 70km east of Tangier. In the morning of 18 July the Alarm Phone was in contact with a group of people on a boat who had embarked near Ceuta. In the end they were intercepted by the Marine Royale.

Alarm Phone regularly gets calls from friends and relatives who are looking for their loved ones. On 12 August a family in Morocco called us as they were desperately searching for a young relative. He had left Ceuta in the night of 11-12 August to go to Spain. He had set out in a kayak with three other people, but since then the family had been unable to reach him. Neither the family nor ourselves were able to find any more information about the group. We do not know if the parents were able to find their son.

On 11 September, Alarm Phone was informed about one person who was trying to swim to Ceuta. It turned out that by the time the Alarm Phone was alerted, the swimmer, a Moroccan national, had already been intercepted at sea by the Guardia Civil and been pushed back to Morocco.

At the end of September one person would appear to have died trying to swim into Ceuta. We were contacted by a relative on 21 September about a missing person. He left from Ksar al Sghir (a little beach between Tanger and Tanger Med) on 20 September 2021 at 3pm local time. The weather was bad. For several days we tried to find out what happened to him, but without success. MRCC Rabat knew about him before we told them, but had not found anybody in that region. On 7 October 2021, we learnt of a corpse washed ashore in Ceuta. The body could have been that of the missing man.

The Alarm Phone team in Tangier reported on the death of 34-year-old Didier Makaula in Rabat, another case that brutally demonstrates the consequences of the criminalisation of people on the move by the Moroccan authorities. On 26 August 2021, Didier Makaula was rudely arrested by agents of the Moroccan auxiliary forces. At the time he was in need of medical attention. He needed to go to the Soussi hospital in Rabat because of a high fever. Despite presenting his medical file that outlined the urgency and complexity of his condition to the agents, he was put in a cell. Despite his worsening health condition and pleas for him to be released, on 29 August the young man, along with other people from south of the Sahara, was forced onto a bus and taken to Agadir. In the evening of the following day, thanks to the help and mobilisation of some comrades, Didier Makaula was able to board a bus back to Rabat in the hope of finally reaching the hospital. Unfortunately, the solidarity did not help. Didier Makaula’s health was so bad that he died on the bus.

We stand with his community who expressed their shock and sadness about yet another unnecessary death on Facebook:

“The sub-Saharan community Morocco faces yet another tragedy, DIDIER MAKAULA’S SUDDEN DEATH IS SHOCKING AND DISTURBING. The young DIDIER MAKAULA has just lost his life in unbelievable circumstances.

It is in widespread confusion and overwhelming shock that the sub-Saharan community (Africans as the locals usually have it) wake up this Sunday, August 29, 2021. And for good reason. It has just lost a son, brother father and friend….

The tragic and violent death of DIDIER MAKAULA, not only leaves the “African” community stunned, but also and above all, it (re)raises the veil on the inhuman and degrading treatment of which “Africans” are victims during identity checks. DIDIER MAKAULA WAS JUST 34 YEARS OLD.”

1.3 North-Eastern Morocco: From Nador to Oujda

Sea crossings and Alarm Phone cases remain low on the routes from the Nador region to mainland Spain. These used to be very busy routes. We dealt with six cases from the region during the period covered by this report. Two cases involved travellers trying to cross from Nador on a jet-ski. Neither case was successful. In the first, three travellers ran into trouble and were eventually picked by the Marine Royale. In the second, on 15 August, another three travellers left on jet-skis but, after also running into trouble, they finally had to swim to safety in Algeria. Three boats carrying Moroccan nationals managed to reach Spain. Two Yemeni nationals were pushed-back from the Spanish islet, Isla del Congreso (see below).

The situation in the region

Many sub-Saharan travellers move from Nador and its surrounding forests or from Oujda and the Algerian border to the city of Berkane. Once there they continue to live in precarious conditions. Life in the forests has particular dangers for women and children. Women frequently report to our local AP Team having suffered from sexual violence and exploitation. Some women also tell of being arrested and pushed back by the Moroccan police on multiple occasions. The common experience is to be held for whole days in prison cells and then to be released at night or pushed back to the ditch at the Algerian-Moroccan border.

In Nador, there are still frequent arrests of sub-Saharan travellers. If you are arrested then, according to our local team, you are first screened and your identity details are checked. After that you are brought to the detention center of Arekmane. This is a new development. Previously you were brought to the central police station or the gendarmerie. By changing the procedure, the Moroccan authorities have now made it impossible for activists or NGOs to intervene. Protests and representations could be made at the police station, but Arekmane is much more of a black hole. Our local members put the change in procedure down to just this issue.

The testimonies of detainees given to AMDH Nador speak of humiliating practices carried out by those in charge of the detention center. Detainees are sometimes woken up around 2 am. Water is poured into the rooms where detainees sleep. The cells are dirty and toilets are filthy. Telephones are seized and all contact with the outside world prohibited.

In the forests around Nador, the situation is as precarious as ever. It is hard to find food and shelter because of the regular violent raids of the Moroccan forces. Many travellers head south, to Laayoune or Dakhla, as it is easier to attempt to cross on the southern routes. Nevertheless, in July we also saw a series of successful crossings in Nador region. These were over the deadly fences into the Spanish enclave of Melilla.

Boza at the fences

On 12 July, around 130 sub-Saharan travellers managed to jump the fences at Barrio Chino. Around 80 more people made the attempt, but failed to reach Melilla and around 20 of them were arrested by the Moroccan Forces. (Source: AP Berkane/ One of the arrested travellers)

On 14 July, 80 travellers tried to jump the fences to Melilla. 25 of them succeeded. (Source: AP Nador)

On 22 July, 238 sub-Saharan travellers, among them many nationals of Sudan and Chad, made it over the fence to Melilla.

On 23 July, two Malian nationals, who were among the group of 22 July, managed to reach Melilla in the Barrio Chino area. There was another attempt made further to the north that day. It seems like two Moroccan nationals made it over. (Source: AMDH Nador)

On 25 July, 40 sub-Saharan travellers tried to jump the fence at Barrio Chino. Seven of them reached the Spanish enclave. (Source: AP Nador)

On 29 July, three sub-Saharan nationals managed to jumped the fences to Melilla. Three other people were injured in the attempt and around 10 to 20 people were arrested. (Source: AMDH Nador)

On 17 August, nearly 60 Sub-Saharan nationals managed to jump the fences at Barrio Chino, Melilla, Spain. (Source: Ap Nador)

On 20 September, 125 people, the majority of the them women and children, jumped the fence at Peñón de Vélez de Gomera. All of them were pushed back. (Source: AP, see below)

On 13 October, 10-20 people jumped the fences and around ten other people were arrested by the Moroccan Forces. Our local Alarm Phone team reports that two people were killed by the Moroccan Forces who had chased them by car.

Apart from these known jumps, from time to time, the authorities and media talk about thwarted attempts. These reports cannot be confirmed by our members or by AMDH Nador. This is despite their constant eye on activities at the border. The authorities claim that on 20 August there was a collective jump of 300 travellers. We have no evidence of this and AMDH Nador called the press release a lie. They said, “This is not the first time that AMDH Nador notes this type of misleading statements that have only one objective: to make everyone believe that the migratory pressure on Melilla is still there and is increasing despite the fact that all statistics show a clear decrease of boooza during the last two years.”

Again, on 1 October, El Faro de Melilla released an article stating that a massive jump of 700 people had been thwarted at the fence. This again could neither be confirmed by our contacts nor by AMDH Nador. “From time to time, Moroccan and Spanish authorities mobilise at night with vehicles and a helicopter against migrants who are far away from the fences“, states the Human Rights organisation.

Hot Deportations/ Push Backs

In the night of 27 July, four young Moroccan harraga tried to reach Melilla from the north of the city (Barranco del Quemadero), three of them climbing the fences and one by swimming. They were detected and arrested by the Spanish Guardia Civil and were deported directly via a door in the fence. Moroccan forces were waiting for them and arrested them. One of them gave testimony of his treatment to AMDH Nador:

“Around 7:30 am, on the morning of July 28, we jumped the barrier and entered Melilla. Immediately we were arrested by the Guardia Civil who tied our hands and drove us back to a gate of the barrier located in Taourirt, north of Mari Ouari. We were received by two members of the [Moroccan] auxiliary forces who delivered us to 3 members of the FAR [Forces Armée Royales] who led us with tied hands to a checkpoint in Taourirt. At this checkpoint, with our hands tied, we were tortured for 20 minutes by two of these soldiers using their belts and their feet, which caused us serious injuries. Afterwards we were delivered to the gendarmes of Beni Chiker who eventually released us […]”

Two of the harraga were minors, and all of them should have had the right to apply for asylum in Spain, even if the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) has endorsed these ‘hot deportations’ at the border and considers them a lawful action by the State Security Forces and Corps in “safeguarding the territorial integrity and protection of the Spanish borders against irregular entry attempts”.

On 18 September, Alarm Phone was informed about two Yemeni nationals that had arrived at 7am at the Chafarinas islands (Isla del Congreso). Despite our immediate intervention and contact to the authorities, they were pushed-back without any chance to apply for asylum. AMDH Nador followed up on the case. One of the travellers testified to AMDH:

“We were treated badly by the Guardia Civil on the Chafarinas islands, who refused to treat us as asylum seekers. When I was able to get a Spanish lawyer on the phone who wanted to explain my situation to the Guardia Civil, they refused [to speak to talk to the lawyer] and confiscated my phone. Around 10:30am we were taken to the Moroccan Marine Royale at sea […].”

The Spanish state and Guardia Civil maintain that people who arrive on these uninhabited islands are castaways. Despite the islands being part of the Spanish state, they are in the Moraccan Search and Rescue (SAR) zone. By insisting that the travellers are castaways, the state can maintain the fiction that the responsibility for ‘rescue’ lies with the competant SAR authority, the Moroccan navy. The Spanish Ombudsman has roundly criticised this approach. They rightly point out that people on the Chafarinas islands are in Spanish territory. They should be granted the right to claim asylum. It is a breach of international law to push people back to Morroco. Needless to say, we agree with the Ombudsman. We hope that the Spanish state returns to its former practice of taking people who are stranded on the Chafarinas islands to Mellila so that they can claim asylum.

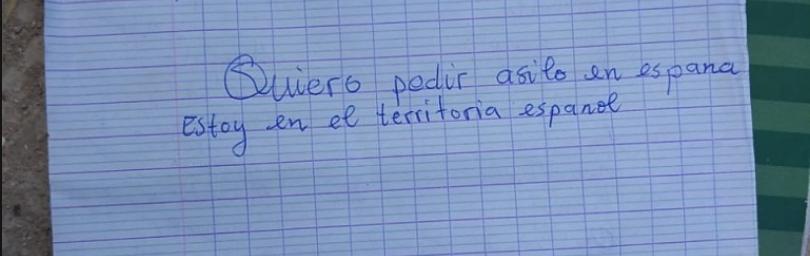

On 20 September, Alarm Phone was involved in the case of a push back of 125 people, a majority of them women and children, who had walked from Nador to the exclave of Peñón de Vélez de Gomera. Some people had health problems or were pregnant and therefore paticularly endangered by their lack of food and water in very hot temperatures. After jumping the fence some people were injured. Alarm Phone tried to intervene with the authorities in Melilla. Those same authorities simply pushed them back to Morocco although all of them had requested international protection once in the Spanish territory. This case shows once again the clear, daily violations of human rights happening on the borders of fortress Europe.

Tweet “Quiero pedir asilo”. Source: Social Media screenshot by AP Maroc

Tweet “Quiero pedir asilo”. Source: Social Media screenshot by AP Maroc

Criminalisation

Many sub-Saharan travellers were caught in and around Nador and prosecuted as key to the facilitation of travel to Europe from that region. Our local contacts report that currently more than five of the locally known contacts for the organisation of sea crossings are in prison at the moment. Others are simply travellers themselves and were targeted without reason, caught, judged in dubious trials and sentenced to long terms in prisons. The major motivation seems to be to artficially inflate the figures of ‘smugglers’ caught to give the impression that the Moroccan state is succesful in the dismantling of trafficking networks. Since October 2018 the authorities have begun to sentence people to ten years in prison. Before then, according to our local comrades, the sentences were three to six months maximum.

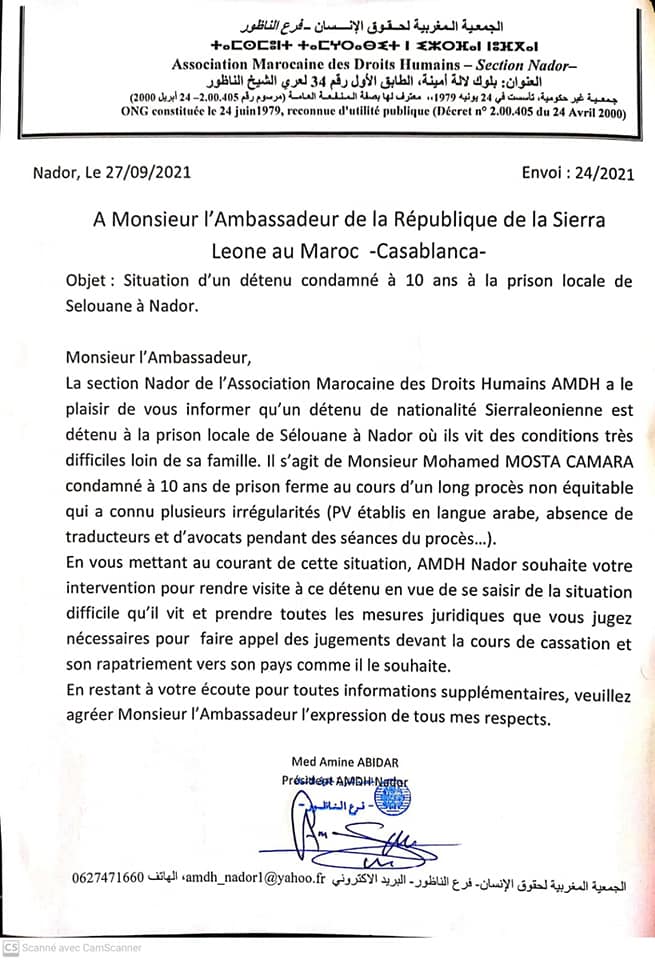

The AMDH Nador has followed several cases of migrants prosecuted by the court of Nador. Omar Naji (AMDH Nador) reports:

“Since 2018, 12 cases have been sentenced to 10 years in closed prison. Eleven are currently in the prison of Selouane in Nador, and one person was recently transferred to the prison of Rabat. Eleven of these sub-Saharan migrants were arrested at sea and suspected of being the drivers of the boats. The twelfth was arrested at the barrier between Melilla and Beni Ensar and, despite this, he was accused of being a trafficker and sentenced to 10 years. These are very heavy sentences resulting from unfair trials during which AMDH Nador has noted several violations: the trial was conducted in Arabic, the absence of a translator and a lawyer during the trial sessions…“.

The condemned are nationals of Senegal, Mali, Burkina Faso, Guinea, Sierra Leona and Mauritania. Our local comrade B. knows one of the prisoners:

“One of the prosecuted is P., a Guinean national. He had arrived in Morocco in September 2018 and disembarked in October 2018 in Al-Hoceima, on a boat carrying 60 passengers in total. The boat went down, and only 30 people survived, rescued by local fishermen. Aboubacar Sidiki Camara woke up in the hospital and was later condemned as organiser of the boat. He was 15 years old at the time of his arrest.“

AMDH Nador sent letters to the ambassadors of Senegal, Mali, Burkina Faso, Guinea, Sierra Leone and Mauritania in Rabat to draw attention to the cases. They asked the authorities to intervene by visiting the detainees to understand the awful situation they are in and then to take the legal measures they deem necessary. One might expect the relevant national governments to assist with filing an appeal and/or moving to repatriate their own nationals.

Letter to the ambassador of Sierra Leone, sent by AMDH Nador.

Letter to the ambassador of Sierra Leone, sent by AMDH Nador.

Moroccan nationals are also arrested and prosecuted for facilitating trafficking. On 3 August, for example, 42 Moroccan nationals were intercepted trying to disembark around Kariat Arekmane. Their boat and petrol was seized by the Moroccan Forces. Three travellers were arrested as supposed members of an organised trafficking network. One member of the Moroccan Forces Auxiliaries, who was carrying a large sum of cash, was also arrested on suspicion of being involved in organising the attempt.

Since August, more and more travellers from Sudan and South Sudan have been staying in Oujda. Some of the people have fled directly from Libya, others from Sudan itself, and some have been brought to Oujda after attempts to cross the border into the EU. The situation there is extremely precarious. Sometimes almost 400 people have to sleep on the streets and beg for food.

There have been repeated brutal attacks by the police. It was reported that on 1 September a café where people from Sudan were gathered was attacked. The equipment of the café was damaged and the Sudanese guests were arrested. In addition, arrests took place after a visit to an association that is the local contact to UNHCR. To add insult to injury, the association is renowned for being of little practical value. People sleep together in public places and on 4 September at around 21h, according to AMDH Nador, the people staying at the sleeping place were attacked by the police.

According to local sources, groups of people repeatedly disappear and no one knows where they are. It is reported that people from these groups appear later in Berkane, a town around 60km away, or other remote localities.

Push-backs to the border area with Algeria continue to take place. Recently a group of people, some of whom have already applied for asylum, were being taken to the desert zone by the police. One affected person reported that, after few hours, a car driver offered to take the group back to Oujda in exchange for the payment of 100 euros. The suspicion is that this person had been tipped off by the police about the push-back before hand. The arbitrary targeting of travellers who are denied any right to a dignified life goes on and on.

1.4 Algeria

Note: In Algeria, there are no Alarm Phone teams and activists, only contacts and friends of friends, so the information in this section is based on a small local network and reliable media articles.

General situation of criminalisation for Algerians and situation at sea

Since the Hirak uprising, Algerian activists and those who rose up during the social movement of 2019-2020 have been heavily targeted by the regime’s repression and surveillance. The repression has not weakened. Very harsh sentences were handed down during trials in October. This repression, combined with the disillusionment following the failure of the Hirak, has pushed a large number of young and elderly people, men, women and families, to go into exile. This phenomenon has been accentuated by the Covid-19 pandemic. According to figures published by the Algerian Ministry of Defense, 4,704 harragas have been intercepted since the beginning of 2021, more than half of them during the month of September. It is known that the women, elderly people and children are taking to the sea in larger and larger numbers (see this video news report “Illegal immigration: more than 15,000 Algerians arrived in Spain in 2021“).

2021 was a particularly deadly year on this route. Nearly 500 people have died trying to reach Spain. Among them are the four people mentioned in this article. Their bodies were found by the Algerian coast guard on 17 October, after their boat capsized off the coast of Algiers. Our hearts and thoughts go out to the deceased and their families.

Fortunately, many people do manage to exercise their right to cross the border. According to figures from the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), between January 1 and September 6, just over 6,000 people arrived in Spain from Algeria through irregular means.

Screenshot of a tweet. Source: Majorca Daily on Twitter

Screenshot of a tweet. Source: Majorca Daily on Twitter

“On the weekend of 18 September, 1,500 Algerian migrants were able to land on Spanish beaches in 80 boats. But four boats sank near the coast, killing 50 migrants, while others are still missing. The boats came from Oran, Boumerdès and even Algiers. On board, there were women and children.” (Source: francetvinfo.fr)

The European side: Control, detention and deportation practices by Spain and France

Faced with the large number of arrivals of boats from Algeria, Spain has adopted a policy of detention and repression against the “smuggling networks” that operate between its territory and the Algerian shores. To this end, it has set up specialised brigades and increased the number of operations to arrest people identified as smugglers. Indeed, the modus operandi of the crossings has changed in Algeria. Though many harragas still chip in to buy and patch up ordinary boats to attempt the crossing, according to this article from the Anadolu Agency media, more and more people are paying up to €4500 to make the trip in less than three hours. These journeys start from the west of Algeria.

Upon arrival, the Spanish authorities pursue a policy of detention and deportation. In this endeavour they are reluctantly supported by the Algerian authorities who have no choice but to take back their numerous nationals whom Europe does not want to welcome. Testimonies and articles show that a significant proportion of Algerians who are intercepted off the Spanish coast spend long periods in detention centres and are then deported in large-scale operations. One such took place on 21 August by ferry to Ghazaouet.

In mid-August, exceptional security arrangements were made to ensure the detention of the large number of people intercepted by the Spanish coast guards off the Balearic Islands. People on board the boats are routinely taken into custody, and those identified as driving the boats are particularly targeted and detained. All passengers risk deportation back to Algeria. We highly doubt that people are granted the right to apply for asylum in anything that resembles a lawful procedure before their deportation.

In France, the increase of crossings at the southwestern border has led to a rise in police checks since the summer. In September, eight Algerians were arrested and accused of transporting people from Spain to France. In a context marked by the campaign for the 2022 presidential elections, the French government is working to secure its borders and to boast about the success of its deportation policy. This creates some tension on the Algerian side.

But above all, the consequences of this policy of control and criminalisation of people on the move are tragically serious. Recently, three people were killed by a train in the French Basque Country. These people, three young Algerians, had taken refuge on the train tracks to rest and escape the numerous, aggressive police checks in the region.

On the Algerian side: counter-productive repression

“The Algerian gendarmerie has spoken of an investigation! An investigation on what exactly? The reasons for their desperation? Their socio-economic distress in a country so rich in potential, but unable to provide them with the slightest glimmer of hope for a better life? No, an investigation into their attempt to leave the country illegally.”

Extract translated from the article, “En un mois, deux enfants morts lors d’une tentative de Harga : les raisons de l’impuissance de l’Algérie face au désespoir des Harragas” (“In one month, two children died in a Harga attempt: the reasons for the powerlessness of Algeria in the face of the despair of Harragas”)

As shown here by the irony of this Algerian journalist, the penalisation of Harga that accompanies the mass exile of Algerians, men, women, children and old people, since 2019 is absurd. Many testimonies and articles agree that the criminalisation of departures has no effect. It perhaps even encourages Algerians to leave, as trials and convictions are seen as further evidence of the injustice that prevails in the country.

“This stupidity of the Algerian regime finally demonstrates that it hardly wants to find real solutions to the evil that is eating away at Algerian society. It is content to play its eternal role: repression and hogra… “

“Hogra” is a concept rooted in the Algerian experience of French colonialism. It describes the humiliation, neglect and oppression inflicted on a population by the powerful and their institutions.

The upsurge in departures since 2019 has been accompanied by a crackdown by the Algerian authorities, and policies aimed at curbing the phenomenon. Irregular migration is governed by laws. Whilst the law 08/11 focuses on penalising irregular entry into the national territory, a law passed in 2009 punishes the act of leaving the territory without documents and outside of official border posts. The offence of “illegal exit from the territory” exposes Algerian nationals to a sentence ranging from two to six months in prison and a fine of 20,000 to 60,000 DA.

According to Fouad Houssam, our local activist contact, currently people who try to leave the country clandestinely, once arrested, are simply given suspended sentences. This does not apply for those identified as smugglers. Despite the strength of the harraga phenomenon in recent months and Algeria’s share of the tragedies at sea, the Algerian justice system has not modified its response.

Faced with European pressure, Algerian authorities have taken to trumpeting the arrests among would-be emigrants. Thus, in August an arrest and a trial of young people who tried to take the sea from Bejaia (Kabylie) took place.

As repression and interception operations at sea have increased, the strategies of the exiles have changed. According to Fouad Houssam, we now see a significant number of departures from the city of Algiers. This is a fairly new. The route is longer and more dangerous, but it avoids the risk of interception by the Algerian navy. Indeed, in the last months, the Alarm Phone was informed of several boats that departed from Algiers (7 August, 18 September, 1 October, 8 October and 17 October). From the western coasts, which are still the most popular routes for harragas, people on the move find tactics to evade the detection of the Algerian Navy.

It is important to note that the boats leaving Algeria are not only occupied by Algerians. In fact, more and more “mixed convoys” with Moroccans and Algerians are leaving from Oran, Mostaganem and Tlemcen, because travel is cheaper there. H., an activist for migrant’s rights in Oujda reports that the criminalisation of Moroccans in Algeria is a worrying problem. In September, a group of Moroccans were intercepted by the Algerian navy, prosecuted, and then sentenced to between six months and two years of prison. People from other countries are found on the boats leaving Algerian shores (sub-Saharan travellers, Syrians), but we lack information and testimonies about their fate after interception.

Still according to F. Houssam, the Algerian reaction to the migration phenomenon remains ambiguous:

“On social networks the phenomenon is making a buzz, with videos taken in the middle of the sea, where Harragas launch messages of revolt against the Algerian system, denouncing injustice, inequalities and the difficulty of life there. The videos showing the young people full of joy at the approach of the Spanish coast make us forget or even ignore the hundreds of disappearances at sea. And it is precisely these videos posted on social networks that fuel the desire of many people from different social classes to migrate through these uncertain migration routes.”

Repression of sub-Saharan travellers

As we have documented repeatedly in previous reports, thanks to the essential work of our comrades at Alarm Phone Sahara, we know that for nearly 20 years Algeria has practiced a policy of hunting, detaining and deporting sub-Saharan travellers en masse to Niger. According to the United Nations, the country, which has no asylum legislation, despite its commitment to the Geneva Convention on Refugee Status, has, since 2014, sent tens of thousands of irregular migrants back across its border.

Since August, here are the deportations that were documented by Alarm Phone Sahara:

On 3, 25 and 27 August, at least 1711 people were deported.

On 29 September and 1 October, 2169 people were expelled from Algeria to Niger in two large convoys.

On 1 October, 1275 people were expelled from Algeria to Niger in a large convoy.

On 9 and 11 October, 1092 people were expelled from Algeria to Niger.

2 Shipwrecks and missing people

On 1 July 2021, eleven people drown off Cherchell, Tipaza, Algeria.

On 3 July, a dead body is found at sea 10 miles away from Valencia, Spain.

On 3 July, a dead body is found at the beach of Bousfer, Algeria.

On 3 July 3, 12 people disappear in the Alboran Sea off Hoceima, Morocco.

On 5 July, two dead bodies are found along the shore of Cherchell, Algeria.

On 6 July, a dead body is washed up El Hamdania beach, Cherchell, Algeria.

On 11 July, a boat with 77 people on board which had left from Boujdour, Western Sahara is found by the Moroccan Navy. At least one person was found dead. Another boat with 23 people on board on their way to the Canaries is still missing.

On 13 July, 16 people die in a shipwreck on the Atlantic route. The boat has left from Boujdour, Western Sahara, with around 30 people on board.

On 14 July, one person dies and 32 survive, 5km off of Aguineguín, Gran Canaria, Spain.

On 21 July, a dead body is found at sea near Almadraba beach, Ceuta, Spain.

On 23 July, a dead body is found at sea near Chorillo beach, Ceuta, Spain.

On 24 July, a dead body is found on San Amaro beach, Ceuta, Spain.

On 27 July, a dead body is found inside a kayak on the coast of the Algerian city of Mostaganem.

On 1 August, two dead bodies are retreived at sea 2 miles off Cherchell coast, Algeria.

On 4 August, at least three people die in a shipwreck close to the coast of Laayoune, Western Sahara.

On 5 August, 42 people are missing after fishermen rescue 10 people from a shipwreck off the coast of N’Tireft, Dakhla, Western Sahara.

On 6 August, the dead bodies of the 42 people are found North of Dakhla.

On 6 August, a dead body is found at sea off Cherchell, Algeria.

On 9 August, 18 people die in a shipwreck off the coast of Tarfaya, Morocco.

On 10 August, 14 people die after a boat with 46 people has been adrift for 14 days. The boat had departed on 28 July from Dakhla and was rescued by a merchant vessel about 650km south of the Canary Islands.

On 10 August, Abdelfattah Charkaoui dies trying to reach Melilla by sea.

On 12 August, a boat with ~47 people that left Dakhla on 28 July is rescued by a merchant vessel 650 km away from the Canaries. Unfortunately, rescue came too late for 13 people.

On 12 August, a dead body is recovered from a fishing boat three nautical miles east of the harbour of Cherchell, Algeria.

On 13 August, 10 people are missing and six people survive after the shipwreck of a dinghy off the coast of Boumerdès, Algeria.

On 13 August, three people are missing after a boat capsizes off Mostaganem, Algeria.

On 17 August, 47 people die on the Atlantic route. Alarm Phone was alerted to a boat with 54 people on board who had left from Laayoune on 3 August. Two weeks later, the boat was found off Nouadhibou in Mauritania, 700km away from the place of departure. Only seven people survived.

On 20 August, 52 people die. Alarm Phone had been alerted to a boat which was carrying 53 people before it was wrecked. Only one person survived. Everyone else drowned after six days at sea and 250 km away from the Canary Islands.

On 22 August, a boat with 65 survivors is found 65km off Fuerteventura, Canary Islands, Spain, at least one person remains missing.

On 22 August, 12 people are missing after a boat goes down in an unspecified location off Cherchell, Algeria. Five people survived.

On 22 August, the remains of two persons – Abdul Haq Walad Qweil and Abdel Nour – are retrieved at sea off Cherchell coasts, Algeria.

On 25 August, ten or eleven people are missing after their boat founders 12km east of Lanzarote, Canary Islands, Spain.

On 25 August, three dead bodies are recovered five miles off Lanzarote, Canary Islands, Spain.

On 25 August, a dead body is found at the beach of Bahía Sur de Ceuta, Spain.

On 25 August, a dead body is washed ashore on the beach of Almina, Fnideq, Morocco.

On 27 August, two dead bodies are found. One on the beach of Riffiine, Fnideq, Morocco and the other one on a beach in Ceuta.

On 27 August, a boat is found 500km southwest of El Hierro, Canary Islands, Spain. 55 people had departed from Dakhla, Western Sahara 12 days earlier and 29 people (many of them children) had lost their lives during the journey. Another woman, who was pregnant, dies upon arriving in the Port of Arguineguín.

On 27 August, at least 43 people are missing after the shipwreck in Northern Senegal of a boat traveling to the Canary Islands. Only 15 people were rescued.

On 27 August, a dead body is found one mile off the coast of Ceuta, Spain.

On 27 August, a boat with 31 people is intercepted and brought to Gran Canaria. Five of the people on board are reported dead.

On 28 August, 18 people are missing after a boat goes down. The boat had left eight days earlier from Agadir, Morocco.

On 30 August, a dead body is found at the beach El Hamdania 2, Cherchell, Algeria.

On 31 August, 11 people are reported dead after a boat with 42 people which had left from Tan-Tan is found 10 miles off Fuerteventura, Canary Islands.

On 31 August, 36 dead bodies are found on the beach of Bir Kunduz, Western Sahara after a boat with 86 people goes down on its way to Canary Islands. 22 dead bodies are found on board.

On 2 September, one person dies while trying to swim across the breakwater at Tarajal, Ceuta, Spain.

On 2 September, one dead body is found in the rocky Fontita area, Arzew, Algeria.

On 12 September, two boats left from Boujdor with only one arriving on the Canary islands, the other one carrying 28 people is missing at sea (Source: Alarm Phone).

On 13 September, a person dies and another is injured after falling off a cliff on the coast of Carboneras, Almería, Spain. They had reached the cliff on board a dinghy .

On 17 September, a boat with 15 person on board capsizes off Boumerdès, Algeria, one person is found dead. 13 people are missing. Only one person survived.

On 19 September, a dead body is washed ashore at Playa de los muertos, Almeria, Spain.

On 20 September, a dead body is found at Garrucha, Almería, Spain.

On 20 September, two dead bodies are found at Puerto del Rey, Almería, Spain.

On 21 September, a dead body is found at Playa el Algarrobico, Almería, Spain.

On 21 September, a dead body is found at Playa Indalo, Mojácar, Almería, Spain.

On 21 September, a dead body is found at Playa Mácenas, Mojácar, Almería, Spain.

On 21 September, one dead body is found at Playa del Lacón, Almería, Spain.

On 22 September, a dead body is found on the coast of Melilla, Spain.

On 27 September, people organise a protest in memory of nine people who have died and for a “unified Mediterranean without more deaths”.

On 30 September, 57 people (28 women, 17 men, 12 children) die when a boat heading for the Canary islands is shipwrecked. Their remains are found 25 km North of Dakhla, Western Sahara.

On 4 October, three people are missing after a shipwreck off the coast of Cabrera (close to Mallorca), Spain.

On 5 October, a corpse is found on the beach of Kheira, Northwest Dakhla, Western Sahara.

On 6 October, two dead bodies are washed ashore near Taourta, Western Sahara.

On 6 October, a dead body is recovered off the coast of Cabrera, Mallorca, Spain.

On 7 October, another dead body is found in Cala Figuera, Mallorca, Spain.

On 7 October, a third body is found off the coast of Cap Blanc, Mallorca, Spain.

On 9 October, 10 people die in the Atlantic Ocean after being adrift for 19 days. 24 survivors are rescued by a merchant vessel 155 kilometers south of Gran Canaria.

On 14 October, at least four people die, three are rescued and 21 remain missing after a shipwreck 37 miles west of Cabo de Trafalgar, Cadiz, Spain. By 18 October, 10 dead bodies will be found in different locations off the coast of Trafalgar, Spain.

On 14 October, a woman gives birth to twins and one of them dies shortly before being rescued, South of Gran Canaria, Canary Islands, Spain.

On 15 October, the Moroccan Navy intercepts a boat that left from Markajmar, Hoceïma, Morocco destabilising it and creating panic. An unknown number of people managed to survive but a dead body is found later.

On 16 October, four dead bodies are recovered after a boat goes down 16 nautical miles north of Algiers, Algeria. 13 people survive.

On 17 October, a boat with one dead body and 44 survivors is found off the coast of Gran Canaria, Spain. It had been at sea one week.

On 17 October, 12 people remain missing, after 2 survivors are rescued from a shipwreck off the coast of Carboneras, Almería, Spain.

On 22 October, Alarm Phone is alerted to a boat on the Atlantic route. The boat carried 13 women, a seven year old girl and 38 men. It had left from Tan Tan, Guelmin, Morocco five days before. 52 people are still missing.

On 23 October, a dead body is found by a fisherman floating near Sidi Abed beach, Hoceima, Morocco.

On 24 October, Alarm Phone is alerted to a boat that left from Dakhla on 16 October. 49 people are rescued after almost two weeks at sea 185km south of Gran Canaria, Canary Islands, Spain. The rescue came too late for one child who died during his attempt to reach Canary Islands.

On 24 October, a dead body is found at the beach of Melilla, Spain.

On 29 October, Alarm Phone is alerted to a boat in distress with 52 people on board on the way to Canary Islands and informs Spanish authorities. During their rescue operation, one person disappears.