Travellers waiting to board a boat towards Canary Islands. Source: AP Maroc

Travellers waiting to board a boat towards Canary Islands. Source: AP Maroc

Our report covers another turbulent four months of crossings, political developments and daily struggles against the European border system in the Western Med. As we described in our last report, the Covid-19 pandemic and the subsequent lockdown in both Morocco and Spain, as well as raids and arbitrary arrests, have had a significant impact on arrivals to Spain. From June onwards, it became clear that both the Spanish and Moroccan state are using Covid-19 as another means of harrassing and arresting migrants (see section 2.3.) or denying them basic necessities like decent accomodation (see 2.3 and 3). Despite these obstacles, people are leaving in search of a better life and fighting for their freedom of movement. The many boats that have made it to Spain, sometimes with the support of our hotline, give us hope and joy. This illustrates again and again that migration can never be discouraged or “stopped”, since it is a fundamental need and a human right. However, these past summer months show a significant change in migration trends in the Western Med. Travellers to Spain now overwhelmingly arrive from Western Sahara (shifting the travel route towards the south) or from Algeria (moving the travel route to the east). These are important changes that require our action and solidarity.

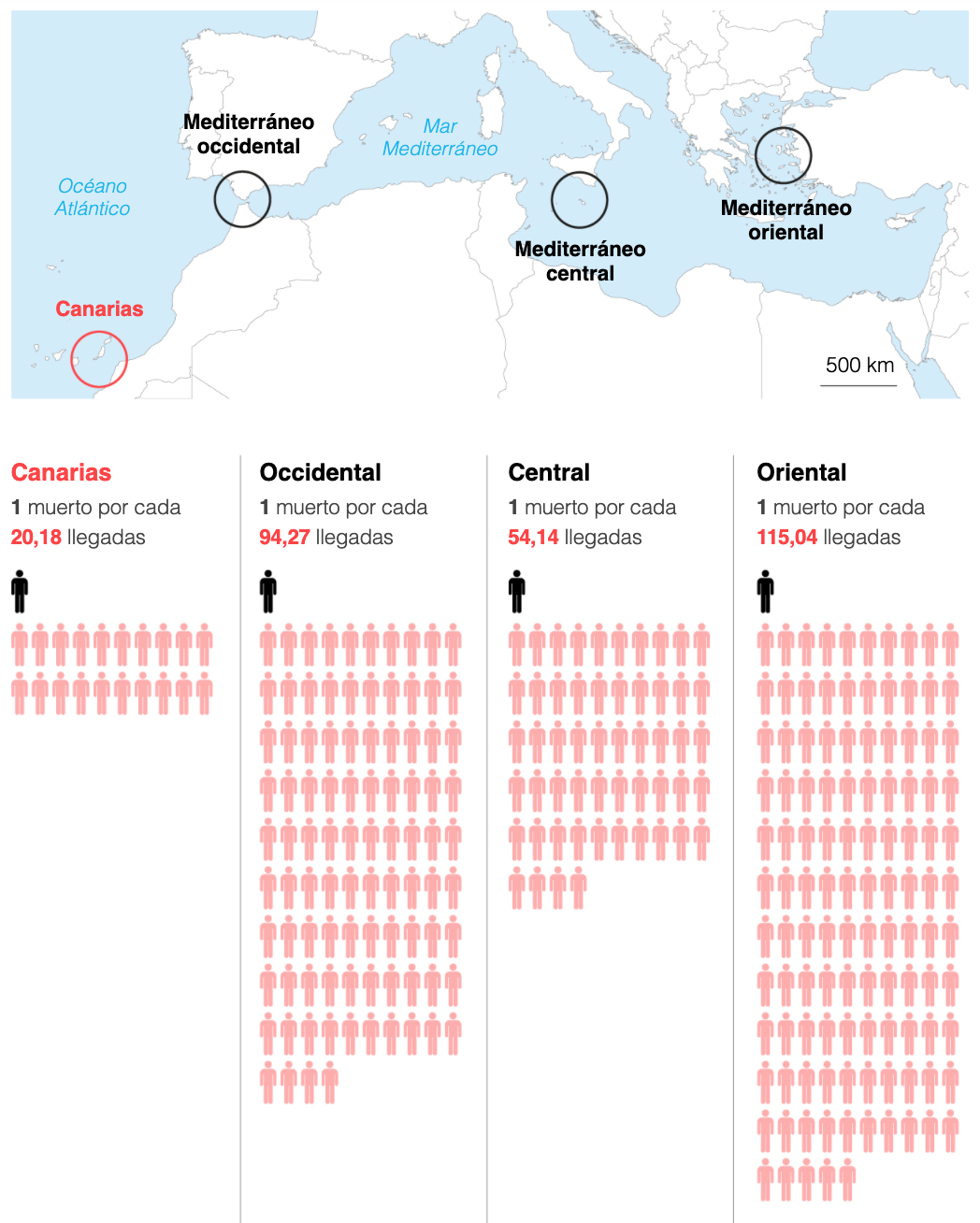

The Canary Islands route has long been known as the most deadly in the Mediterranean. So far 2020 has exacerbated this trend. There have been more and more departures from Mauritania, Senegal and The Gambia, way to the South of the Canaries, and several shipwrecks. Travellers have to spend days, sometimes even a week at sea, almost always confronted by adverse wind and weather conditions. Their only hope is rescue by Salvamento Maritimo, but the Spanish Search and Rescure organisation’s patrol area is a million square kilometres. This is a hopelessly vast territory if a boat has lost its way, an engine has failed and the people on board have no means of communication from out in the Atlantic.

Comparison of number of arrivals per death at sea between different routes towards Europe.

Comparison of number of arrivals per death at sea between different routes towards Europe.

Source: IOM, Figure: El Pais

People wanting to leave Morocco often do not have any other choice. State control in the North of the kingdom is extremely tight and goes hand-in-glove with ever increasing anti-migrant repression. This has led to a massive inflation in the price of travel. The number of arrivals to the Canary Islands, just over 6000, is still far from the so-called “crisis de los cayucos” in 2006, when more than 30,000 people made the crossing in wooden fisherboats from Mauritania and Senegal. Still, we are extremely worried about every single departure. As activists fighting for freedom of movement and as human beings we have to redouble our efforts to scandalize and end this death trap.

The second big development is a sharp increase in arrivals from Algeria. From January until August, 41% percent of all travellers to Spain were Algerian nationals (compared to 8% in the equivalent period in 2019). As always, the reasons are manifold. The political system under former President Bouteflika and the seemingly intractable socio-economic crisis often lead to the decision to leave the country. The crisis triggered by Covid-19 and the countermeasures taken to prevent its spread have made daily life even harder for many people. Since an Algerian passports gives you almost no prospect of obtaining a visa for the EU, Algerians are forced to take the dangerous sea route. Just like their Moroccan neighbours, they are immediately seperated from other arrivals and fast tracked through deportation procedures. Algerians are quickly and forcibly returned to Algeria.

As Alarm Phone we are trying to expand our networks and are working on an Algeria section for future reports. Moroccan and Algerian travellers make up 60% of all arrivals. As we have highlighted in the past, we do not wish to reproduce unnecessary distinctions between different nationalities. However, both Alarm Phone and the wider ‘no borders’ solidarity network need to be more aware of the situation peculiar to North African nationals so that we can extend our bonds of solidarity to people on all the migration routes in the Western Med.

Content

1 Sea crossings and AP experiences

2.1 Tangier and the Strait of Gibraltar

2.5 The enclaves: Ceuta and Melilla

4 Shipwrecks and missing people

As always, we base our report-writing on the voices of the AP members on the ground, adopting a perspective of agency and resistance. Our goal is not journalistic objectivity, but the tearing down of fortress Europe.

1 Sea crossings and AP experiences

As of 27 September 2020, 19,093 people have arrived in Spain this year. 17,693 of them via the Mediterranean sea. 11,260 travellers arrived in the Balearic Islands and to the mainland, whilst 6,116 reached the Canary Islands. 1,395 people arrived via land into the Spanish enclaves of Ceuta and Melilla (UNHCR, 2020).

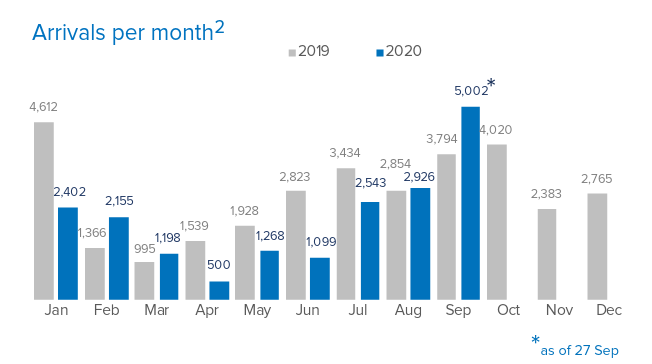

61% of the arrivals in 2020 entered Spain in the past 4 months, with 5,002 in September alone. Furthermore, there has been a sharp increase in arrivals since Covid-19 measures started easing in Spain in May 2020. These numbers are illustrated in the graph below.

Arrivals per month comparison between 2019 and 2020.

Source: UNHCR Spain Weekly Report, Week 21 – 27 September 2020

In the Western Mediterranean, Alarm Phone was busier from June to September (39 cases) than January to June (29 cases). In the period covered by this report, 20 boats arrived in Spain, whereas 10 were intercepted. Alarm Phone recorded two shipwrecks, one boat missing and one illegal pushback. Furthermore, the fate of five boat remains unclear.

Some Alarm Phone cases from the past four months

On 31 July, at 04:50 CEST, we received a call from a person who knew people in a boat which had left from the area around Tantan and Gulmin. They were heading for the Canary Islands. He informed us that the boat had left on 30 July at 07:00 CEST with 30 people on board. He gave us phone numbers of the people on the boat. We tried to contact the people on the boat, however, they were not reachable. We contacted Salvamento Marítimo and the Guardia Civil to inform them about the boat in need of help. The people on the boat remained unreachable. After almost 18 hours of waiting, we received an email from Guardia Civil Las Palmas informing us that the boat had been rescued. BOZA! Welcome to Europe!

On 11 September at 08:35 CEST, we received a call from a person in a boat that had landed on Peñón de Alhucemas, one of the Alhucemas Islands, Spanish territory only 0.7km from Morocco. They informed us that they were a group of 5 people from Cameroon, that they were very cold and that a woman on the boat was ill. Despite having arrived in Spanish territory, Spanish authorities returned the 5 people to Morocco. There was no administrative procedure and so they were denied their right to claim asylum. This is a clear violation of the law. We condemn Spanish authorities for these actions. Solidarity with our brothers and sisters from Cameroon and the many others who face these criminal ‘hot deportations’.

2 News from the regions

2.1 Tangier and the Strait of Gibraltar

Since July, AP members report that they have rarely witnessed police controls in Tangier. This is an artefact of the state’s response to Covid-19. Control operations have tended to be concentrated in the city center, while communities of migrants mainly live in outlying neighborhoods or the forests surrounding the city. As an Alarm Phone member puts it, “the lockdown is not yet effective in Tangier.”

Nevertheless, there have been cases of eviction and deportation. These have involved women and children as well as men. On July 28, a group of almost 50 people were arrested at the Tangier train station and forcibly relocated to a center in Rabat. There were also evictions in Bukhalef and Mesnana. These are neighborhoods on the outskirts of Tangier where communities of migrants live, mostly hidden in so called “tranquilo” (dwellings), in constant fear of running into the arms of the police. Alarm Phone members also report that they were informed by the victims of arrests in Tangier and deportations on September 29.People were brought in buses to the central region of the country, Casablanca, and Rabat. One member reports that there are attacks by moroccan citizens on sub-Saharan migrants on a daily basis.

Although controls are concentrated in the city center of Tangier, people waiting to cross in the forest near the city are subjected to controls and sometimes violent arrests. On July 31st, one young Cameroonian, Félix, died in suspiscious circumstances after being stopped and stripped, along with a number of other people, by members of the Moroccan Auxiliary Forces in a forest near Tangier. According to the testimonies collected by the AMDH (Moroccan Association for Human Rights) of several of those who were with him, Félix died after he received violent blows to the head. It was several hours before an ambulance arrived. In a two-minute video that was widely shared on social media, young people carry Felix’s body, shouting “Moroccans killed our brother”. An investigation has been opened by the Moroccan authorities to determine the circumstances and causes of his death. On the European side, the Spanish union, General Confederation of Labor (Confederación General del Trabajo, CGT) demanded that Spain acknowledge its responsibility for this tragedy, explaining that it is a “consequence of what is lived or undergone in the border regions” because of the externalisation of the border regime by Spain and Europe to third countries.

With regard to crossings, attempts happen all the time, but most people are intercepted by the Moroccan Navy. Thus, on July 21, the Royal Moroccan Navy annouced that more than 100 people were intercepted at sea and sent back to the ports of Nador and Tangier. Successful crossings from Tangier are no longer a frequent occurance and some have deadly consequences. On July 22, out of a convoy of 14 people, 6 died in the Strait of Gibraltar, while 8 reached Algeciras. There were victories in recent months. On August 12, five people found their way to Ceuta and, as reported by activist Helena Maleno, on August 9 and 11, four convoys from Tangier with 26 people reached Algeciras.

In recent times, most people have started their journey from the beaches some kilometers to the South of Tangier. In general, the increased security measures on the beaches of Tangier mean that people are more likely to head south, especially to Layounne and Dakhla but also to Mauritania, to take the boat. One member expects that this situation will continue for the time being. However, as the weather worsens, there may be a decline in the number of boats. Nevertheless, Alarm Phone members fear that crossings will continue despite the coming winter and harshening control measures making it even more dangerous to cross the sea.

2.2 Nador and the forests

The situation in the forests around Nador has always been tense. People in transit hide and wait for their chance to cross the Alborán Sea or to the nearby Spanish enclave Melilla, but with the Covid-19 confinement it has been getting much harder to survive. Even though raids and arrests by the police have declined, it is much more difficult and risky to ask for food or donations on the roads towards Nador. In addition, with the economic crisis in Nador city, it is harder than ever to find cash-in-hand work. With a disastrous sanitary situation in the makeshift camps and little access to healthcare in the city, your life is in danger in the forests. There are no official records of deaths, but burials of sub-Saharans in collective graves are seen in a cemetry in Zoutiya. Once in a while concrete news spreads about new deaths in the forest.

The closure of the border with Melilla, an important trade partner, as well as the lockdown, led to four months of economic stagnation. The Moroccan government has not managed to revive the local economic and the situation for the residents is tense. During the lockdown and throughout July important weekly markets were closed. Street vendors and merchants were violently attacked and arrested. In their statement of July 10, the AMDH also criticises the acute lack of access to health care and food aid for sub-Saharan people in transit. Most local associations suspended their programmes during the lockdown. It was only in mid-July that a few slowly restarted organisation of food relief and basic support for people in urgent need, mostly pregnant women.

The state is also using this moment to extend its control over the humanitarian sector. The AMDH spoke out against a newly created application, “RefAid”. Officially RefAid is meant to facilitate access to emergency relief for people in need, but it also collects data on the locations of its users. The worry is that it could be an important tool for the Moroccan state, enabling authorities to track people’s movements in the forest.

The number of attempts by sub-Saharans to cross to Spain remains low, but some of those attempts have been lethal. On July 31, two bodies were brought to the Hassani hospital in Nador. They had drowned in a shipwreck off Ras el Ma, a small town to the east of Nador. We know of only a few successful crossings from the sub-Saharan communities. The 16 and 23 August are two such examples. On each occassion, two sub-Saharan travellers managed to reach Chafarinas and were eventually transferred to Melilla.

In sharp contrast to the difficulties sub-Saharans have faced in resuming crossings, Moroccan nationals from Nador seem to leave the city in astonishing numbers. The AMDH Nador sees this phenomenon as a direct effect of the state’s failure to protect the local economy:

It must be noted that the current increase in departures of Nadorians who leave for Spain by various means clearly coincides with the impoverishment measures implemented by the authorities of Nador against large segments of the population: the closure of souks and shops, seizure of goods from local merchants, and closing doors for Moroccan workers in Melilla. A real economic and social crisis to which the authorities are not offering any solution to these thousands of excluded citizens, except repression and a ban on protests. At the same time the floodgates seem to be open for the departure of young people.

The number of crossings of the Alboran sea rose steadily over the last three months. There are also intermittent spikes in the data. These crossings were mainly undertaken by Moroccan and Algerian nationals.

On July 8, Salvamento Maritimo and the Guardia Civil picked up 70 travellers from 5 different boats on their way towards the coast of Murcia.

On July 20, two boats carrying 116 passengers were rescued by Salvamento in the Alboran Sea.

On July 24/25, we witnessed the highest number of arrivals, with 454 people arriving on the coast of Murcia.

On August 28, 184 travellers reached Murcia in 13 inflatable dinghies.

On September 13/14, the Cruz Roja/The Red Cross report that within 48 hours, 250 people reached Alméria in 16 or 17 different boats.

On September 21/22, within 24 hours, 13 boats carrying 170 travellers from Algeria arrived on the Spanish coast around Murcia. The same night, 64 Moroccan nationals were rescued by Salvamento Marítimo in the Alboràn Sea from 4 different boats. In addition, 198 travellers from 13 more dinghies reached the Balearic islands.

In the past the groups of people travelling together across the Alboràn Sea have tended to be larger. These dinghies, in general, only had only around 10 people on board. How the journeys across the Alboran Sea will develop and if sub-Saharan travellers will resume attempting to make the Alboran crossing remains to be seen.

2.3 The Western Saharan route

As we have see these last few months, there have been more and more boats which leave Mauritania and Senegal, and in August there was an increase in arrivals to the Canary Islands from Mauritania and Senegal. There are also arrivals from places like Laayoune, Dakhla, Tarfaya and Tan Tan. There are hundreds of arrivals in some weeks.

This report by Alarm Phone member B. from Laayoune sums up the development in recent months of the Canary Islands route. While there has been a significant drop in arrivals elsewhere in the Western Med, this does not hold true for the Canary Islands. According to the UNHCR, 1460 travellers arrived between June and August 2020 (in addition to the 2555 arrivals from January to May). September saw another vast increase in arrivals, with more than 2000 people making it, bringing the total number of arrivals in Canary Islands in 2020 to 6116 people (as of September 27). This is 6 times higher than the same period in 2019. A fifth of these people are women. In other regions of the Western Med, only 6% of travellers are female. The high numbers of arrivals, especially in September, meant that there were several weeks with hundreds of arrivals. Sometimes there were hundreds within a day, such as on September 6 which saw 140 arrivals in six boats; September 8, 160 arrivals in seven boats; and September 15, 130 arrivals in ten boats.

In August, several boat crossings made the headlines, in particular a series of tragedies between Mauritania, Western Sahara and Canary Islands. In the first days of August, 7 deaths occurred in a boat with around 60 people. The boat was later saved by the Marine Royale, but another 13 people remain missing. There was another tragedy with 10 deaths and 10 survivors not far from Dakhla while a boat was found adrift not far from Nouadhibou with 28 dead and just one survivor. Only two weeks later, there were another two shipwrecks found south of Gran Canaria, the first with 6 deaths and 9 survivors and the second with 15 deaths but no survivors. This last boat had probably departed from Nouadhibou. Its passengers died from dehydration. According to Alarm Phone activist B., the resurgence of this lethal route is due to a shift in Moroccan border management:

Two years ago, Morocco introduced travel restrictions for certain countries such as Guinea, Mali, Congo and others, that’s why certain people were stuck in Nouakchott or Nouadhibou. These people started creating their own travel networks from there. Morocco thinks that it can sort out the problem with these restrictions, but they are only making things worse. The point of departure is further and further south and that’s too dangerous. People can easily get lost at sea.The engine can fail. There are many risks and we can expect many more shipwrecks on the Canary Islands route.

[…] There are many Moroccans among the travellers, which illustrates the hardship of young Moroccans, the reason why they look for a better life elsewhere. Just like the sub-Saharan travellers who cross the deserts, risk their lives and think that once in Europe, their misery will be over.

Yet, on the Canary Islands, their hardship is far from over. The past months have greatly exacerbated the situation. With no transfers of people to the Spanish mainland, capacities are already beyond breaking point. For the past two months in particular, new arrivals have been forced to camp on the asphalt in the harbour upon arrival, sleep in sports grounds, port warehouses or even tourist complexes. Since Covid-19 tests were made mandatory for travellers in June, there have been days of waiting in makeshift tent structures and deplorable conditions under the blazing sun with temperatures above 40°C. The port of Arguineguín has been hosting between 300 and 450 people in the past weeks and the moorings are crowded with the vacated wooden boats used for the journey.

Empty boats in the Arguineguín harbour in September 2020. Source: cadenaser.com / Europa Press

While the authorities are trying to create more capacity, there is also an urgent need to reorganize the general system of Covid-19 testing and accomodation upon arrival. New arrivals are already being redistributed amongst the different islands (e.g to Tenerifa instead of Gran Canaria), which can create confusing and dangerous situations of miscoordination, such as on September 21 when a Salvamar vessel received contradictory instructions as to whether proceed with a rescue and as to where to take them (see secion 4 Spanish Migratory Policies). But without transfers to the mainland, we can expect the situation to worsen in the months to come. Opening more CIEs and re-launching deportation flights (see section 4) is NOT an acceptable solution!

Even during the Corona crisis, the Spanish state continued to carry out deportations, although at a reduced rate. The testimony of a person deported from Gran Canaria to Mauretania in July 2020 shows that they are often arbitary and based on scanty evidence:

I had travelled to Mauretania, and then we had BOZA! We had spent five days on the water. The day we were taken, we were so exhausted. Then we were in Las Palmas, for a week and one month. In the week after they were supposed to set us free, but a Mauritanian offical came and said we had left from Mauretania. We said no, that we had left further north, but… That’s how we came back to Mauretania.

(Source: AP Maroc)

In Morocco, Covid-19 has also had a heavy impact and is an excuse for repression and arbitary state control. When 14 travellers on a boat to Fuerteventura tested positive upon their arrival in Spain, Morocco launched a campaign of forced Covid-19-tests against sub-Saharan people in Laayoune. Police officers broke into houses, arrested people in the streets or in their businesses and put them into detention. The police claimed that the testing procedure would last for four hours, but, in fact, people ended up detained for 5-7 days, in horrible conditions, without clothes or adequate access to water and food. As one AP source states, people were taken from their homes and tested “like sheep”. Black people are confronted with the widespread suspicion that they bear the virus – another racist assumption. The AMDH Morocco opposes these pratices and points out that Corona is being used as yet another instrument for controlling and detaining sub-Saharan people.

June 25, Laayoune: Police keep Black people in detention, allegedly for Covid-19 tests.

Source: AP Maroc

In another detention centre in Tarfaya, a group of nearly 50 people had been detained for weeks when some of them attempted a break-out at the end of June by jumping out of the windows. They were recaptured and brought back to the centre. The authorities responded by filling the windows with bricks and cement, leaving the detainees in unbearably hot rooms with a lack of oxygen.

Arbitrary arrest and detention are not the only racist practices sub-Saharan travellers face. With the ongoing policy of dumping intercepted passengers in the North of the country, sub-Saharans have to pay around €200 for the journey back to Western Sahara. Several bus companies have also increased fares between destiations within Western Sahara. Alarm Phone member K. explains the situation as follows:

At the moment, you have to negotiate. It’s between 500dh and 700dh [€50-€70] between Tan Tan and Laayoune. The same holds for Laayoune to Dakhla. […] Travel agencies like SUPRA TOUR ask you for your residence card, the agency GAZALA categorically refuses the sale of tickets, CTM agency pretend that they have no seats available anymore. After asking several times on different days, it was clear to me that its not about space on a bus, but about my skin colour.

2.4 Oujda

Members of Alarm Phone Oujda report that since July, inhabitants of the area around the Moroccan – Algerian border have noted increased militarization. Despite the lack of official announcements, families on both sides of the border state that more military is visible. The demonstrations against the closure of the border between Morocco and Algeria have completely stopped due to the Covid-19 pandemic.

The region of Oujda continues to be the place to which people on the move are forcibly displaced by the Moroccan authorities. In the period from July 15 to September 27, Alarm Phone Oujda were informed of 115 people, amongst them seven women and eight minors, who were brought by force from Rabat, Nador, Tetouan, Casablanca and Tanger to the no mans land at the border. As is so often the case, people were left between midnight and 04:00 close to the village of Tiouli in the region of Jerrada.

The general proceedure is that, after a long trip with very little food or water, you are robbed of your phones and money and sometimes you are beaten up. In this difficult condition, you have to try to walk to Oujda, the closest town. This takes between one or two days, but sometimes more than a week, depending on health conditions. In Oujda, women are chased away from roundabouts, where they have to beg for money in order to survive. Sometimes the police take you far from the city and then you have to struggle back. People in Oujda report that there is also a growing number of children and minors living alone on the streets. There is no state care of minors, even if officially the state is obliged to look after unaccompanied children.

In terms of criminalization, Alarm Phone Oujda is following eleven cases of people who have been arrested because of law 02.03, concerning the organisation of papers for strangers and migrants in Morocco. The accused are currently imprisoned in Oujda, Berkane and Zaio charged with illegal entry to Moroccan territory and face one to three years in prison. As Morocco denies visas to most foreign nationals, it is interesting to have a closer look at who exactly gets imprisoned by this law. Experience shows it is mostly people who do a lot of work to support their communities and activists in migrant struggles. Court cases do not follow proper proceedures. Papers are in Arabic and not translated into languages that the accused can read, there are no translators at hearings and people do not have the right to legal representation. Often the trial is carried out so fast that the accused has no time to prepare a defense. This can only be seen as a form of repression against inconvenient activists whom the state consider to be too brazen in demanding their rights.

2.5 The enclaves: Ceuta and Melilla

Despite restrictions due to Covid-19, so-called ‘hot deportations’ (which are not recognised by the Spanish government as such) and interceptions by Salvamento Marítimo or the Guardía Civil, people are continuing to find ways to cross over to the Spanish enclaves and from there to the Spanish peninsula. ‘Reverse’ BOZAs back to Morocco continue to take place, as it was only at the very end of September that Morocco said that it would allow the return of a few hundred of its citizens. Moroccan nationals have been stuck in the enclaves since the closure of the border on March 13. According to the UNCHR, since our last report, 152 people crossed via land into the enclaves of Ceuta and Melilla and about 330 via sea (260 into Ceuta, 70 into Melilla). Here are some examples of how people still exercise their right to freedom of movement:

On August 25, another ‘reverse’ BOZA took place when a woman managed to swim back into Morocco under the eyes of bathers and people on their boats.

On September 27, seven people made it via boat into Ceuta and were rescued by Salvamento Marítimo.

In order to prevent people from climbing into the enclaves, both Moroccan and Spanish authorities are reinforcing the border fences around the enclaves at the cost of billions of Euros and many lives. Not only has the height of the fences been increased to up to 10 metres and their foundations been strengthened but in June the barbed wire on top of the Spanish border fences was replaced with curved tubes‚ “peines”.

Spanish border fence with new anti-climbing cylinders. Source: Redouan M.J.

Spanish border fence with new anti-climbing cylinders. Source: Redouan M.J.

They are going to be supplemented with anti-climbing cylinders, making it even more difficult to jump, and giving the Guardia Civil more time to arrive at border crossing attempts. This will facilitate the practice of hot-deportations and leave no legal pathways for forced migrants to enter the enclaves. While the Spanish interior ministry is presenting the new fence as a more humane and ‘less bloody’ way to prevent crossings (or freedom of movement for all), it hides the fact that massive amounts of barbed wire are being installed on the other side of the border. It makes sure that the next time brutal photos of mutilated people or broken corpses cause widespread condemnation the finger will be pointed towards Morocco. A neat solution to Spain’s PR problem.

Spanish and Morrocan border fences at Benzu area. Source: Redouan M.J.

Meanwhile the situation for migrants in the enclaves, be it on the streets or in camps like the CETIs (Centros de Estancia Temporal de Inmigrantes, detention centres for migrants in Spain) continues to be unbearable. When the Spanish Supreme Court ruled in July that asylum seekers in Ceuta or Melilla have the right to move to the Spanish mainlaind after their asylum application has been accepted, there was hope that some people would finally be transferred to the peninsula, somewhat relieving the situation in the camps. But so far there has been no implementation whatsoever, even after an outbreak of Covid-19 infections in the CETI in Melilla. Instead of letting people pass to the Spanish peninsula, the government used the overcrowding of the camps to legitmize the deportation of 600 Tunesians from Melilla. All of these measures were met with protest, both in the camps and on the streets of the enclaves.

3 Spanish Migration Policy

For a long while now, Spanish migration policies have been based on the externalisation of borders, detention, deportation and bureaucratic obstacles to regularization. The number of agreements with third countries grow as the number of arrivals in Spanish territory from third countries increases. During the summer holidays the minister of Home Affairs, Grande-Marlaska, visited Algeria with the aim of “opening up new areas of cooperation” on irregular migration. This can be attributed to the fact that so far this year 46% of boat arrivals in Spain via the Straits of Gibraltar and the Alboran sea left from Algeria (compared with 5% in 2018 and 10% in 2019).

Another clear example of the externalisation of borders and the repressive Spanish migratory policy is exemplified by the fact that the Ministry of Home Affairs has tripled the subsidies to African countries for curbing irregular migration. Morocco, has been a privileged partner for a long time. Recently, however, money transfers have also increased to Guinea Conakry, Mali, Côte d’Ivoire and The Gambia. In 2020, the minister of Home Affairs, Fernando Grande-Marlaska, issued a directive which donates police equipment with a value of 1.5 million euros to seven African countries (Côte d’Ivoire, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea Conakry, Mauritania, Senegal and also Tunisia) to help them ‘tackle irregular migration’. Tunisia gets included because Spain aims to strengthen its relationship with the republic to prevent the transit of Tunisians through Melilla.

We are witnessing a militarisation that has never been seen before along the southern border in Spain. The Guardia Civil and Frontex, both military formations without any experience or specialisation in rescue operations are replacing the forces of Salvamento Marítimo – civilian Search and Rescue professionals with more than 25 years of experience. The General Work Confederation (CGT), the main trade union of the SAR operatives, is opposed to life and death decisions being taken by military personel with no knowledge of the sea in offices thousands of kilometres away from the distress site. The various maritime coordination centres no longer work together creating extremely dangerous situations. This was well illustrated in an example from September 21. In a recording spread among emergency services personnel, the Salvamar Menkalinam captain can be heard telling the control tower, “I am with the dinghy. Tell me how to proceed!”. The Menkalinam received the order to leave the rescue to the Guardia Civil, although she was already alongside the dinghy. When the rescue boat had to leave the dinghy adrift once more, the Salvamer skipper can be heard fuming. He said, “This can’t happen. The decisions need to be made before we reach the distress site (…) I am putting peoples’ lives at risk”.

Ismael Furió, secretary of the CGT organisation, explains that a situation in which the people in the dinghy think that they are going to be rescued and then get told that rescue is not forthcoming can cause enormous fear. It can trigger panic reactions that may lead people to jump into the sea to try to reach the rescue boat. Furió states that this dangerous and uncoordinated situations could have been completely avoided. The CGT also decries the practice of basing rescue decisions on mercantilist reasons, such as which detention centre has space or where the next deportation flight is leaving from. The obvious implication is that SAR decisions are no longer aiming at saving lives. One has to agree with the skipper of the SM Menkalinam that people’s lives are being put at risk by the new set-up. As Alarm Phone, we urgently call for effective coordination between the different actors involved for the sole purpose of saving lives.

On the 24th of September, the Ministry of Home Affairs reopened the eight detention centres for migrants (Centros de Internamiento de Extranjeros, CIE) in Spanish territory. They had been closed for five months because of Covid-19. Now, they will operate as usual. They will hold people who are in Spain irregularly in preparation for a future expulsion. This decision was announced soon after Marlaska’s visit to Mauritania to discuss the increase in arrivals to the Canary Islands. Mauritania readmits migrants from third countries, if they left from Mauritania to go to Spain (Spain has had a similar agreement with Morocco since 1992. It was reactivated by Marlaska when he got in power).

Yet, there have been some positive legal developments in late September. The detention and expulsion policies underwent a change because of a precedent setting court case on the Canary Islands. The judge relied on a decision of the European Court of Justice from 2013. This new decision means that the judge presiding over an internment hearing is now considered as a competent authority to receive an application for international protection. Before this ruling, the only authority competent to accept a request for asylum was a police officer. According to the Immigration subcomission of the Tenerife Bar Association “Up until now, police officers did asylum applications when migrants were in the CIE, even if they should have done them before. There are people who claim asylum upon reaching land. This ruling which considers judges to be competent authorities befor whom one can ask for asylum guarantees that the applicants do not enter a detention centre, but rather go to a centre for humanitarian support. This is a game changer”.

Duty lawyers and a judge thus managed to prevent the deportation of 31 migrants with Malian origin on Frontex deportations flights, respecting the UNCHR’s view that people should not be deported to Mali.

4 Shipwrecks and missing people

On July 18, Alarm Phone reported a boat with 63 people on board missing on its way to Canary islands. We have not been able to find any trace of them since.

On July 22, 6 people died in a shipwreck in the Strait of Gibraltar, only 8 people survived, as reported by Caminando Fronteras.

On July 23, a body was found 1 nautical mile off the coast of Morro Jable, Fuerteventura.

On July 30, the body of a young man was recovered among 9 survivors off the coast of Almería.

On July 30, a body of a young Algerian national was recovered off Almeria among 12 survivors who had been drifting for several days at sea.

On July 30, two Sub Saharan nationals drowned in a shipwreck off Ras el Ma. The 13 survivors were brought back to Morocco.

On August 3, a boat carrying 11 people capsized on its way to Amería. Only 3 people could be rescued alive and one body was recovered. The other 7 travellers remain missing.

On August 3, 7 people died and 13 remain missing from a boat carrying 60 people that capsized off Tarfaya on its way to the canary islands, as reported by Caminando Fronteras.

On August 5, 10 people drowned southeast of Dakhla, while 10 others survived.

On August 5, 27people drowned off Nouadibou, Mauritania, leaving only 1 survivor.

On August 19, 15 travellers die 81 miles south-west of Gran Canaria. Salvamento assets found the 15 corpses on board the dinghy, probably dead from dehydration.

On August 20, 5 people were found dead and a sixth passed away on his way to the hospital, when 11 travellers were rescued 110 miles south of Gran Canaria.

On August 22, 11 Algerian nationals went missing whilst 4 were rescued from a dinghy in the Alborán Sea.

On August 30, two Syrian nationals died while trying to cross from the beach of Ras el Ma on a jetski.

On September 1, the body of a woman was found floating off Chafarinas. She could not be identified further.

On September 5, a body washed ashore at Melilla.

On September 7, the remains of a drowned body was washed ashore at Restinga beach, Fnideq.

On September 8, 2 people died, presumably from dehydration or hypothermia.Their boat, which carried 58 passengers in total towards the Canary islands, was rescued 5 km off Santa Cruz de Tenerife.

On September 9, an unidentifiable body is discovered floating off Chafarinas.

On September 17, a father and his two kids died in a shipwreck carrying 12 people close to Habibas island, Bouzedjar comune, Algeria. The mother remains missing,

On September 29, after their departure from Ceuta, 3 people died in the Alborán Sea, after several days adrift, only one person was rescued. They were brought to Almería.

As Alarm Phone, we are sad and angry about every death at sea. They are political murders and we will continue to fight for freedom of movement for everyone.