Source: A. Janda

1. Introduction

Children on their way to Europe are often overlooked; their specific needs, their extreme vulnerability, but also their cleverness in finding ways to travel are often invisible. And what is worst, the fact itself that they are children is often overlooked or hidden behind the discourse of “minors” or acronyms like “MENAs” (Menores Extranjeros No Acompañados, unaccompanied foreign minors). Whether we speak of children or use some bureaucratic terminology is political in itself, for this terminology contributes to the dehumanisation of the most vulnerable humans that are most in need of protection: children.

Of course, it makes sense to point out whether these children are accompanied by a parent or relative, or completely have to depend on themselves (which is expressed by the terminology of ‘unaccompanied minor’). It also makes sense to name the fact that they are separated from their parents, or isolated, as the terminology of ‘isolated minor’, an older synonym for ‘un-accompanied minor’, suggests. Whatever the adjective, the emphasis should always be on the fact that they are children, that they are experiencing violence, suffering and trauma that no human should have to go through and that children are not equipped to deal with. This is why, for this analysis, we will speak of children on the move or migrant children, always aware that no matter what they seek to achieve, where they wish to travel, they are primarily children and deserve our unconditional protection and support.

The topic of children on the move itself is very current and has dominated the Spanish debate on migration in the past months. The increase of arrivals on the Canary Islands has prominently raised the topic of children’s rights, since the accommodation facilities are not at all equipped to respond to their needs (see section 3.1.). Similarly, children entering the Spanish enclaves (on Moroccan territory) have recently received a lot of media coverage, for example when 57 children entered Ceuta swimming within three days in February. Sections 3.2 and 3.3 will detail the situation of children in the north of Morocco, particularly at the land borders of the enclaves. All sections for the different regions will show the reality of the racism and violence that children on the move experience along the Western Mediterranean and Atlantic route, be it in the countries of departure (sections 3.1-3.5) or in the Spanish state (section 3.6).

As usual, this analysis will also provide an overview of sea crossings, statistics and Alarm Phone cases of the past six months (section 2), as well as a list of all those who did not survive (section 4). We are thinking of them, our respect and solidarity are with their families.

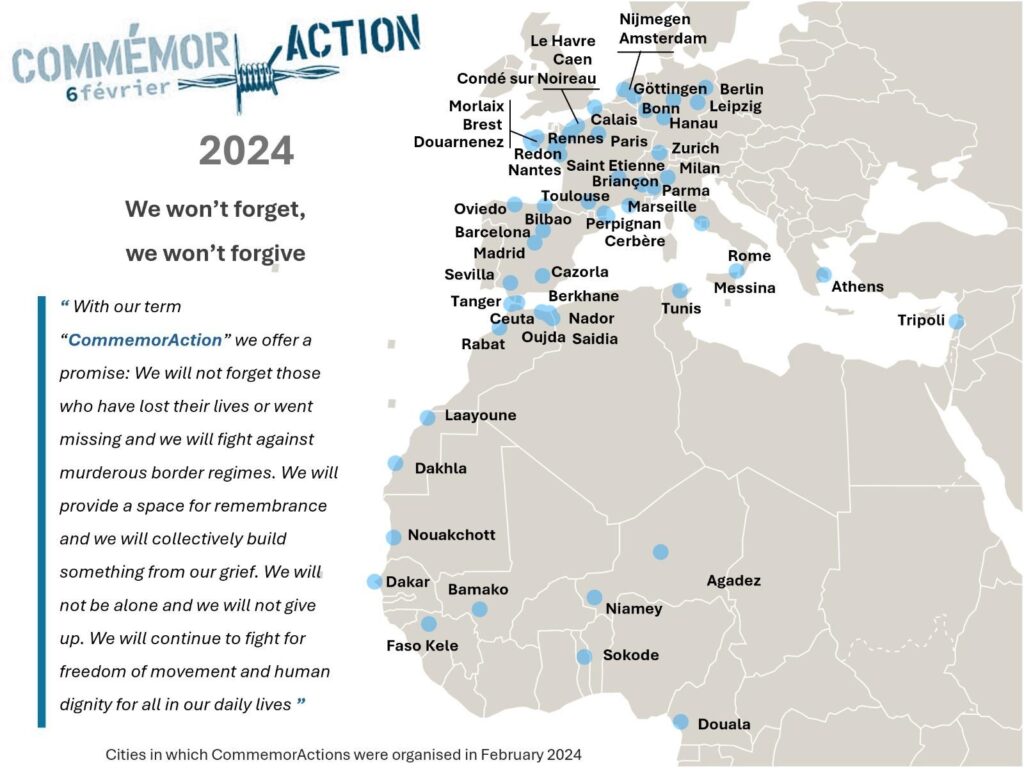

To express our grief and rage, we have organised commemorActions all across Europe, Northern and Western Africa (see section 5), to commemorate the 10th anniversary of the 6th of February massacre by the Guardia Civil. We feel empowered by our unity and we draw strength from these events to continue fighting.

In most countries around the Western Mediterranean region and the Atlantic, children theoretically enjoy an array of rights and protection. Most countries have ratified the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (Morocco in 1993, Spain in 1990, Algeria in 1992, for example). Children should therefore be protected generally as members of the international community, as persons, as well as particularly as children. Where migration law intrinsically differentiates between the nationals and the “others”, the protection of children does not: all children around the world, no matter their administrative status, must be protected without discrimination.

“In all actions concerning children, whether undertaken by public or private social welfare institutions, courts of law, administrative authorities or legislative bodies, the best interests of the child shall be a primary consideration” (Art. 3-1 United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child).

But as always, a child, once perceived as different, as “other” by the authorities, becomes a suspect: their minority is questioned based on racist prejudices and perceptions, their childhood is denied and replaced by their otherness. The obsession with fighting against people on the move minimises the perception of children as persons in need of protection, of their rights, life and childhood.

In Morocco, a significant part of the migrant population consists of children: 10% for both accompanied and unaccompanied children, according to figures from 2018, out of which 35% are girls, whereas a UNICEF report from 2019 mentions that 10% of the migrant population alone are unaccompanied children, with 18% of the migrant population being under 14 years old. According to the same report, around half of the migrant children do not have documents. In general, it is illegal to deport a child who entered the country without a visa, and access to basic services is not dependent on a residence permit. Indeed, the requirement to possess documents only applies to adults. As this analysis shows, however, all this is the legal theory; the practice is vastly different in the countries around the Western Mediterranean and the Atlantic. As Alarm Phone, we are outraged by the sheer neglect and abuse that migrant children are exposed to on their dangerous journey to Europe. Children should normally have the right to health, including vaccinations, to a good and balanced nutrition, to education, to play and to recreation. As the report shows it, the access to those rights is, as often, subordinated to the illegal discretion of the local authorities. As M., a 16-year-old student from a public school in Tangier, explains, the application of the educational directives and laws depends on “the goodwill and mood of the teaching staff and school management, but also the number of black children enrolled in a school”.

A., a member of Alarm Phone Morocco, is the mother of a little girl who was born seven years ago in Morocco. She explained how racism is impacting her and her daughter, as all other children “with a migration background”:

“as with many other children of immigrant origin, it didn’t take me long to realise that many of the difficulties faced by our children are common, and most often linked to the colour of their skin”.

Like the adults, children face the violence of racism and the border regime. The entire family is infiltrated by the repercussions and incidents of the border regime: It impacts not only their childhood, but also each member of their family and the stability and quietness they should have. L., a member of Alarm Phone Morocco, reports:

“Children are stressed because their parents are stressed. Because when a parent is faced with a situation, their child is also going through the same situation, the child is experiencing the same problem. Their situation is not stable”.

In school also, many children experience racist comments and acts. G., a student in CE1 (2nd year of elementary school) in a private school in Rabat with a good reputation relates: “I’m always the guilty one in the class; my voice, my opinion, my truth doesn’t count; I’m the only black person in my class.” When L., a member of Alarm Phone, had to move, her child got worried about changing school and facing new racial discrimination. She explains:

“When I said to her, ‘We’re going to look for a house somewhere else, I’m going to look for a school for you’, she asked me, ‘Will there be people with the same skin as me in the school you’re going to take me to?’”

Racism infiltrates each step in the daily journey of each child on the move: from accessing basic rights to their day-to-day interactions with other children and adults that are supposed to protect and take care of them.

The rights of children to be heard, to speak up and to participate should be recognized.

“Children have the right to give their opinions freely on issues that affect them. Adults should listen and take children seriously” (UN, explication of Art. 13 UNCRC).

But are they heard? Children are mostly excluded from the political conversation on their rights and protection, even when they are often the main actors of their survival, as this report shows. Children on the move are often caught in a double trap: On the one hand authorities perceive them as suspects, not totally children anymore. On the other hand, children are reduced and essentialised in most political narratives (from states to some NGOs and international organisations) to a status of victims of adults that could exploit them: they should thus be protected by ‘carceral solutions’ (i.e. by criminalising adults and by being subjected to care/control institutions). The institutionalised protection often offered to children is based on narratives in which their vulnerability is constructed around racialised, validist and gendered categories. Subtle forms of care-control technologies are often used to stablise and control children on the move or prove to be insufficient to really fulfil the needs expressed by children on the move. While we do not deny the reality of the exploitation of children, the humanitarian discourses of authorities are often used as scapegoats for their own agendas (the fight against migration) and their own responsibility. It is first and foremost the border and carceral regimes that endanger, and sometimes kill, children.

Nonetheless, other forms of solidarity towards and between children on the move and their families exist. This report tries to emphasise the numerous ways children, their families and supports use in order to survive and fulfil basic needs.

A., a member of Alarm Phone, explains that children

“feel that links with members of their community are important; these links serve as a refuge for them and have a social and cultural context that is nourished by sharing the same situation”.

Focusing our report on children was our way to participate in the visibilisation of often dissmissed and invisibilise lives: if their deaths often used to criminalise adults after a shipwreck, the voices of children and their realities are too often silenced, as well as those of their parents and friends.

2. Sea crossings & statistics

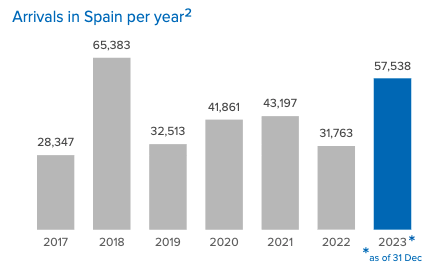

According to the UNHCR, 57,538 people arrived in Spain in 2023. Compared to 2022, arrivals have thus increased by 81%, especially on the route to the Canary Islands: with 40,330 arrivals, the difference here is 157% compared to the previous year.

Figure 1 Arrivals in Spain per year. Source: UNHCR SPAIN Weekly snapshot – Week 52 (25-31 Dec 2023)

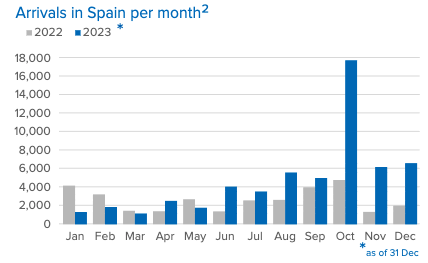

Overall, Alarm Phone was in contact with at least 6,729 people during the course of 2023. Out of 265 cases, 120 concerned boats on the Atlantic route, 87 in the Alboran Sea or the Strait of Gibraltar and another 55 boats Alarm Phone dealt with had departed from Algeria. In accordance with UNHCR figures, which show an immense increase of arrivals to Spain in October 2023, Alarm Phone also received many calls from more than a thousand people on the Western Meditarranean and Atlantic route in this month, most of them calling from the Atlantic.

Figure 2: Arrivals in Spain per month. Source: UNHCR SPAIN

In November 2023, Alarm Phone was informed about many boats that had departed from Algeria. Unfortunately, in most of these cases, the fate of the people remains unclear, and at least 18 people were reported to be dead. We are very sad and angry about the hundreds of people that we certainly know of to have died on the Western Mediterranean and Atlantic route in 2023, as well as the several hundreds of people who remain missing (see also section 4: Shipwrecks & missing people).

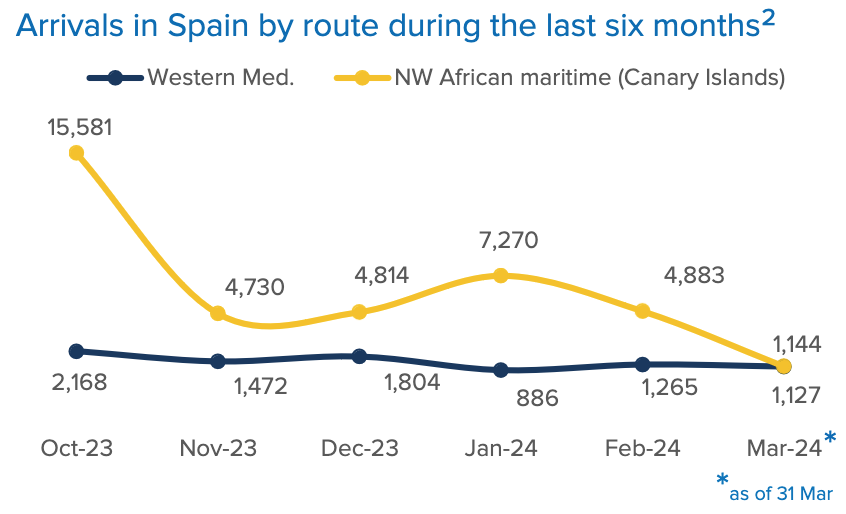

As of March 31, 16,575 people have arrived in Spain so far in 2024. Compared to 2023, these figures by the UNHCR show an increase of arrivals by +279%, or even +501% on the Atlantic route towards the Canary Islands. Remarkably, most of these arrivals were happening in January of this year, whereas in March numbers dropped significantly.

Figure 3: Arrivals in Spain in the last six months. Source: UNHCR SPAIN

Out of 22 boats in the Western Meditarranean and Atlantic region that Alarm Phone was in contact with, most called in January and February. Every second boat called from the Atlantic. As was also apparent towards the end of last year, we are receiving more calls from or regarding boats from Algeria, but unfortunately in most of these cases we do still not have info.

For at least 131 people who contacted us on their way to Spain, we could not find out what happened to them (as of March 31). Furthermore, 266 people on these routes were reported missing, like 65 missing people who had departed from Nouakchott in the middle of January. Of the remaining 302 people Alarm Phone spoke to, some were brought back to Morocco or Algeria but most got rescued or arrived in Spain by themselves.

3.News from the different regions

3.1. The Atlantic route

2023 was a year of record arrivals. Not even during the historical 2006 “crisis de los cayucos” (Spanish term for wooden fisherboat) were arrival numbers as high: 40,330 people arrived in the Canary Islands in 2023; we are extremely happy that so many people survived the journey. Yet, 2023 is also a year of record deaths on the Atlantic route. While official UNHCR data only count 950 dead or missing on this route, the NGO Caminando Fronteras published much higher and – in our opinion – much more realistic numbers: 6,007 people died or went missing on their journey towards the Canaries, with 128 shipwrecks on the route.

In 2024, this tendency seems to be continuing. As of March 31, 13,297 people had already arrived in the Canaries, six times more than in the same period of 2023.

The route itself has also undergone significant changes: Many boats now arrive at Gran Canaria and El Hierro (in the first weeks of 2024, 55% of all boats arrived at El Hierro), indicating that the main regions of departure are now Mauritania and Senegal, no longer Western Sahara. This is also mirrored in who calls our distress hotline: Since the beginning of the year, 5/6 of all Alarm Phone cases on that route had left from Mauritania.

In the past six months, most departures on the Atlantic route left from Mauritania, for example from the fishing port of Nouadhibou. Source: AP Laayoune

Given the high number of boats leaving from Mauritanian shores, the European Union is engaging in it’s usual dirty game of border externalisation: In early February, the Spanish Prime Minister and the President of the European Commission travelled to Mauritania in order to tighten the political cooperation regarding border controls, thus again turning Mauritania into the EU’s border watchdog. While Mauritania has already received 600 million € in the past, another 10.5 million € was granted in October 2023.

Of course, departures from the south of Morocco and Western Sahara are still ongoing; however, most people crossing are of Moroccan or Sahrawi origin. Members from Alarm Phone Laayoune explain:

“Currently, Moroccan nationals cross more frequently than people from West/Central Africa. The first three months of 2024, approximately 1400 people managed to get BOZA (“Victory”, the word for successful arrivals in Bambara). […] Young Moroccans are also facing very difficult situations; there is no work and they are fed up.”

One reason for this shift is the travel route being available further south, in Mauritania, but also increased security measures: “In the past six months, we observe that fewer boats leave from the south and from the Sahara due to the reinforcement of surveillance posts: There are 118 checkpoints along the 300 km of departure beaches”, as reported by Alarm Phone Laayoune.

Evidently, the number of people arriving has been a challenge for accommodation and infrastructure in the Canary Islands. Due to the dramatic increase of arrivals of the past six months, especially the island of El Hierro with a population of not even 12,000 inhabitants is struggling to accommodate the survivors.

Children arriving in the Canaries: deficits in child protection, neglect and assaults

In such extremely difficult circumstances, as usual, children are even more vulnerable than adults. In recent months, around 20% of arrivals on the Atlantic route have been children, a large majority of them unaccompanied.

At present, the Government of the Canary Islands has 5,700 children under its care, and the numbers are constantly rising. In addition, around 1,000 people are waiting for their status as minors to be recognised by the Spanish authorities.

The increase in the number of children arriving alone is resulting in the opening of new emergency centres or a saturation of capacities of the existing centres, leading to serious shortcomings in children’s care and protection, the identification of their specific needs in terms of international protection or human trafficking, and the psychosocial support that should be provided.

UNICEF Save the Children and Amnesty International have identified serious deficits in the identification of children travelling alone. Recurrently, children are housed with adults both in CATEs (Centros de Atención Temporal de Extranjeros – detention centres where people arriving by sea spend the first 72 hours under police surveillance) and in accommodation centres for adults.

A report entitled “Maritime arrivals in the Canaries: exceptionality of the law and racism” produced by the Irídia and Novact associations points out the violations of human rights and children’s rights during the age determination procedures established in the Canaries. When a person declares themselves to be a “minor”, even if they have documents indicating their minority, the age determination procedure must be carried out in order for the Spanish state to recognise the person’s status as a minor. In their report, Irídia and Novact denounce the racist nature of this measure: “This provision calls into question the reliability of the minor’s word [and of] documents that are considered ‘not very reliable’ [because they are not] Spanish or European.” Furthermore, access to a legal representative and an interpreter is just as problematic for children as it is for all migrants.

The lack of an effective and consistent territorial distribution between the autonomous regions makes it difficult to guarantee children’s rights and decent reception conditions. All the more so as child protection services complain of a lack of financial resources commensurate with needs. Furthermore, while it is difficult to convince other regions to take in children, this is also the case for the Canary Islands’ municipalities, which often refuse to agree to the establishment of reception centres in their districts.

Recently, in Lanzarote, the issue took a very alarming turn. Following a racist attack on a bus by three unaccompanied children staying at the reception centre in the village of La Santa, the Cabildo (the island authority) and the company responsible for running the centre (Fundación Respuesta Social Siglo XXI) reached an agreement whereby children would no longer use public transport. From now on, they must be accompanied by a guardian or travel only on private transport belonging to the company. The measure was publicly announced by the councillor in charge of social services as temporary and supposedly taken to “protect children” from further racist attacks. This discriminatory and arbitrary measure responds more to the societal alarm created for the purposes of political instrumentalisation than to the vulnerable situation of the group of unaccompanied children. The measure has been denounced by the collective Red de solidaridad con las personas migrantes de Lanzarote and by the leftist Izquierda Unida Canaria political party.

Outrageous conditions: Sexual assaults, embezzlement and children in prison

Despite this, the Canary Islands authorities and the companies responsible for running the reception centres receive substantial sums of money for child protection. Yet, the lack of solidarity from other regions cannot be used as an excuse for the largely poor management and intolerable failings in child protection.

On 26 November 2023, 12 boys aged between 14 and 17 filed a complaint alleging that they had been assaulted, threatened and molested by employees and the director of the Tafira centre for minors (Gran Canaria) run by the Fundación Respuesta Social Siglo XXI. The young victims had fled the centre and the police initially refused to take their complaint, leaving them on the street.

The same entity, Fundación Respuesta Social Siglo XXI, is being investigated by the anti-corruption prosecutor’s office for misappropriation of public funds. Four directors of centres for minors are being investigated, one of whom was also secretary and treasurer of the far-right Vox party at the time she ran the centre.

However, despite the corruption and sexual abuse scandals, no measures have been taken regarding the management of the centres by this company. Still on the subject of corruption, on 29 February 2024, the Canary Islands Government’s Director of Child Protection was forced to resign. She was accused of misappropriating public funds between 2015 and 2016 when she was a councillor for the town council of Puerto de la Cruz (Tenerife).

Another case illustrating the many abuses suffered by children from reception centres is that of a farmer accused of illegally employing minors on his land. The man’s daughter is the director of a centre, and she allegedly allowed him to employ these young people for €20 a day for long working days, money that could be deducted from them if their behaviour in the centre was considered to be bad.

The criminalisation of migration is also claiming victims among children. There are more and more cases of children being held in preventive detention in the Canaries, presumed guilty of being the captains of the boats in which they arrived. This was the case for a young Senegalese man suspected of being the captain of a boat in December 2023, who – despite having proved his age by means of a birth certificate – had to spend two months in prison because the authorities did not believe him to be a minor.

Children in countries of departure

Across the ocean, migrant children are also subject to numerous forms of abuse. In the south of Morocco and Western Sahara, children are often treated as if they were adults; no heed is paid to children’s rights: “They are often victims of police aggression during raids in migrants’ houses. Children are arrested and treated the same way as adults,” report members of Alarm Phone Laayoune.

This is why migrant children have to turn to the few associations on the ground which will support them by trying to bring them to a hospital, cover some medical bills and help them getting enrolled at school. Many of the children are unaccompanied and thus have to try and survive by their own means. Alarm Phone Laayoune explains:

“Migrant children live in shared houses with other people who want to travel and contribute to the expenses for food. They work as beggars in the street. I had to intervene many times and to go the police station, because minors had been arrested begging at traffic lights.”

A woman with her child, begging on the streets of Laayoune. In the Sahara, many migrant children live in the same destitute situation as their parents. Source: Alarm Phone Laayoune

When it comes to Senegal, the phenomenon of children leaving for Europe without any family member is not as widespread. There are some examples where Senegalese parents were punished by prison for having allowed their children to embark on a boat which then shipwrecked. Many of the unaccompanied children leaving from Senegalese shores are of Guinean origin. Children and adolescents decide to travel for various reasons: they flee from violence and misery, search for a better life or hope to join family members already in Europe. As Alarm Phone Dakar details:

“In 2006, for example, 931 so-called ‘unaccompanied minors’ of Senegalese nationality arrived in the Canary Islands. Recently, in late 2023, this same phenomenon has repeated itself due to a politically instable situation which leaves no choice to an already desperate youth. These children who left Senegal to travel to Europe via boat sometimes even depart from Mauritania or The Gambia.”

3.2. Tangier, Strait of Gibraltar & Ceuta

Tarajal beach on 6 February 2024. Source: A. Janda

From Tangier to Ceuta and the Strait of Gibraltar, children are defying the borders despite tireless repression from the Spanish and Moroccan authorities and are fighting for their rights and survival. Examples of children swimming to Ceuta or boarding in precarious embarcations to cross the Mediterranean are numerous.

S., a child from Guinea Conakry, tells us about his life in Tangier:

“I’ve been living in Tangier for years now as an unaccompagnied minor. I’ve encountered unimaginable difficulties here in Tangier. I’ve slept in the forest, in churches, even in the street because I didn’t have any money.”

Often left alone, children struggle to access basic needs such as food, shelter or clothes. Indeed, children are autonomous in their own survival. They rely on their communities and on each other. Some of them are forced to share a small and insalubrious room in groups of six to eight so as to afford rent and to save some money to prepare their departure. Others live in the forest, where they cook and sleep, before going to the city in the morning to beg or carry luggage.

Children are exposed to daily abuse, violence and exploitation. Young girls can be forced to work and be raped by older men. When pregnant, they are often rejected and abandoned on the streets on their own. Sexual violence against children on the move is sustained by a climate of racism and impunity that expose children to violence from civilians as well as from the authorities.

As L., a member of Alarm Phone Tangier, explains:

“Except in few cases of murder, rape or other serious problems, the authorities do not intervene. Children are left alone. There is no protection for them.”

There are testimonies of children being arrested by the police, stripped of the few belongings they manage to gather and sent back to the streets or to the other side of the border.

In the face of this situation of children in Morocco, several associations try to offer some support to children. Some associations try to support children in accessing health professionals or in purchasing medicines. Other associations propose professional training programs that can support children in learning about cooking and baking, sewing, hairdressing, aesthetics, IT, carpentry, ironwork, electricity or even painting. For children aged from six to 17, some associations are also in charge of enrolling them at school. But few children succeed in following the courses while struggling for their daily survival.Those who manage to follow and finish the training are confronted with new obstacles: the lack of papers that prevents them from finding a legalised job and the small protection that it could give them.

For the families, accessing basic rights and needs are, as numerous of our reports have shown, a daily struggle. Some parents explained that they had to withdraw their children from school to support them in the search for the money necessary to feed the family. L. testifies about the impasse the system put her in, forcing her to ask her 13-year-old girl to come begging with her in the streets of Tangier:

“I’m from Senegal and I have a 13-year-old daughter. Life in Morocco is very difficult; there’s no work at all. Sometimes we’re offered cleaning work in very difficult conditions. You go to work from 8 am to 7 pm; sometimes you even have to sleep there to be at their disposal 24 hours a day. And all this for a lousy salary. So now I prefer to do my jewellery business to feed my children, but it’s not enough. There’s rent, bills and other expenses to pay.

That’s why, when my 13-year-old daughter leaves school, I push her to go and get Salam (begging) to help me pay the bills. Otherwise I’d never be able to cope. I know it’s not right, but children make more money begging, so I have no choice.”

S. from Guinea Conakry continues his testimony: “And the police bother us too much, they take us away from Tangier to throw us in Casablanca or Safi.” More than not supporting, the authorities are often, as with adults, harrassing the children and subjecting them to forced displacements to southern cities in Morocco.

When children successfully cross the border in Ceuta, they unfortunately are also victims of pushbacks by the Spanish authorities. When this happens, testimonies show that, like adults, they are beaten and mistreated by the police.

On 14 December 2023, the repression of an important attempt to cross the border of Ceuta resulted in many persons being injured or killed. Many of them where children from the south of the Sahara. Members of Alarm Phone went to meet them at the hospital and tried to find a housing solution. To identify all the victims of state repression was not an easy task as the Moroccan authorities scattered the injured in different hospitals to prevent potential media coverage and attention to what happened. A member of Alarm Phone met with a young boy who had received a bullet in his left eye that was shot by a policeman. He explains that the same policeman forced him to leave the hospital and to destroy his medical file.

In Ceuta, many children are kept in reception centers, waiting for protection from the Spanish authorities. In the beginning of February, the Ceuta authorities sought assistance from the national Ministry of Children and Youth after over 30 Moroccan children managed to cross the border in two days. More than 180 children were kept in those centers at the time, against the principle that children should not be locked up.

Despite the violence they are subjected to, children continue to try to cross the borders, swimming to Ceuta despite the heightened security, moving South to try to cross to the Canaries or travelling to Tunisia and attempting to cross to Italy. The force and survival skills they show are unimaginable, but we cannot stress enough the fact that nobody, children included, should have to face this violence. Violence that is created and reinforced by every political decision made by states.

3.3. Nador

News from the Nador region

The period covered by this report is characterised by further fortification of the Melilla (EU) border and further restriction of the freedom of movement in the area.

The works on the new, third fence on Moroccan territory were finished in January, as AMDH Nador observes. “Never before seen anywhere in the world: a 7 m-high barrier of razor wire (forbidden on the Spanish side). Not only that, but the rolls of barbed wire were laid on the ground along the strip separating the old and new barriers, in addition to a new pit almost 3 m deep”, the Moroccan Human Rights Organisation describes the fence.

“All this oversized equipment, with thousands of soldiers, police officers, auxiliary forces and gendarmes mobilised 24 hours a day upstream and along the fence […] – with all these measures, we are further than ever from the demands of the Moroccan national movement for the decolonisation of Melilla.

The Spanish state is using the migration issue as a scarecrow to maintain the colonisation of this town forever, and the Moroccan authorities are patting Spain’s colonial migration policies on the back for pitiful funding.

And of course, everyone on the Moroccan side remains silent. Neither political parties, nor trade unions, nor parliamentarians, nor NGOs, nor even our press dare to denounce or at least expose this blind policy to public discussion. The border with the occupied town of Melilla is a matter for all Moroccans.”

For Alarm Phone, it is clear that these measures of border control intend again and again to maintain a colonialist system of separation, and to deter people by violence from challenging the status quo of power asymmetries by overcoming physical division.

Apart from reinforcements at the border fences, there are also new attempts to further obstruct sea crossings. As AMDH Nador denounced in February, a ban of Moroccan citizens from the coastal zone between Arekmane beach in the east and Kalat in the west of Melilla was established in early 2024 (as part of the fight against migration). In total, f these restrictions of free movement are inplemented in four municipalities.

But despite all these measures, we are sure that migration can’t be suffocated, and people will find ways to overcome borders, as the case of 8 October shows, when a person managed to cross these lethal fences into Melilla by paragliding! Boza!

The situation of unaccompanied children in Nador province

There is a high number of Moroccan-national unaccompanied children that arrive in Nador province without parents or relatives with the intention to cross to the Spanish peninsula. These so-called ‘harraga’ are thus internally displaced people on the move, and their situation is in some aspects similar to the situation of the non-Moroccan communities of departure, in some aspects of course very different.

The Moroccan children arrive from different regions of Morocco, mainly from Fes, Casablanca, Safi and southern Morocco. The reasons for leaving their respective families and homes are manifold – because of difficult situations in their families, due to social marginalisation or economic hardship. Some seek to rejoin their familiy members who are already based in the EU.

The Moroccan harraga live in very precarious conditions in Nador province. They live in the streets, rely on begging in order to feed themselves, and are often victims of discriminations. A big risk to their health is the widespread consumption of drugs – many harraga are dependent on drugs like opium, glue or some chemical substance that is used to make house paint. C. from the local Alarm Phone network estimates that 98% of the children are addicted to some drug or substance. Polyconsumption creates dependency at an early age. These drugs are used to treat very strong anxieties linked to the various forms of violence associated with migration, and to living conditions that are often unbearable. These conditions are particularly prone to the chronicisation of psychological disorders.

The Moroccan authorities are often conducting operations in the zones where most children are present, waiting for their chance to cross to Spain. Though these children are not undocumented and legally have the right to travel within Morocco wherever they want, the police frequently arrests them and deports them to places further south in Morocco (like Casablanca or Safi), not unlike the undocumented people from Western and Central African communities on the move.

The conditions under which children are forcefully displaced are often deplorable. Children are often detained in unsanitary and overcrowded conditions before being taken on the buses that forcefully displace them, they barely receive any food or water. They are deprived of their fundamental rights, in particular their right to protection and privacy.

“The forced displacements of the minors have harmful consequences for their health and development” observes C.

“Minors are often traumatised by their experience and are more likely to develop psychological and physical problems. They are also more likely to end up in dangerous situations, including prostitution and crime.”

These displacements of the harraga are conducted to avoid overcrowding and ‘migratory pressure’ in the border zone, but C. guesses that they are also aimed at mitigating the degree of danger that the harraga face while staying in Nador and of course, during the crossing attempts. There are often accidents, sometimes lethal ones, during the dangerous crossings. Every week there are more than five fatalities. The children climb under the trucks that leave for the port, or the buses that travel by boat. They fall and die, sometimes from cranial fractures. Sometimes they drown while trying to swim towards Melilla, or they climb through tunnels for electric cables where there’s not enough oxygen, and they die of asphyxiation in the holes.

In the period covered by this report, October 2023 to March 2024, the forced displacements of children on the move described above continued to happen quite frequently. On 6 November, around a hundred Moroccan children tried to jump the fences to Melilla. Everyone was blocked and/or arrested by the Moroccan authorities. AMDH Nador tries to document the displacements on their Facebook page, including the case of 5 December, when 24 children were refouled from Beni Ensar. In late 2023, during the last days of December, raids and arrests intensified significantly among the Moroccan children in Beni Ensar. 175 people on the move were arrested on 31 December alone, many of them Moroccan youth. 4 dead bodies were recovered the same night: Officially, the children had died falling from a clifftop between Beni Ensar and Gourougou, but the AMDH estimates that their death is related to the intense police raids in the area that same night.

Unaccompanied children from other African countries

There is also a significant group of unaccompanied children from outside Morocco, mainly from other African countries, such as Sudan, Cameroon, Guinea, Nigeria or Senegal (among others). They are stranded in Morocco on their way to Europe. They are mostly staying in Morocco undocumented, without legal status. They are living amongst the adult migrant communities in the same precarious conditions, mostly in makeshift camps in the forests around the city of Nador. They are also dependent on begging for their food, and on NGO support for hygiene and health care.

3.4. Oujda & the East

In Oujda, the situation for children on the move is quite challenging. The Moroccan Organisation of Human Rights (OMDH) serves as the primary entry point for migrants, but most arrive without proper documentation or deliberately conceal it. In Oujda, possessing such documentation can provide access to a range of much-needed services, including medical care, registration of newborns, participation in training programs, and utilisation of services offered by various associations. Since people on the move have very little access to social services in general, some of them provide false information to claim protection from UNHCR.

Most of the children coming to Oujda come from the Algerian border. The journey to Oujda is very difficult, and to cross the border from Algeria to Morocco, one must have sufficient money or protection from others. Most of the children, accompanied or not, arrive in Oujda with various diseases, injuries, fractures or psychological disorders. For girls, the suffering is often doubled since they often survived sexualised violence. They may arrive with a sexually transmitted disease or an unwanted pregnancy, and they usually travel in groups or with a man who is responsible for “protecting” them, often in exchange for money or sexual “favours”. Upon arrival in Oujda, they may be sold to other men or forced into prostitution or other types of forced labor.

Most children come to Oujda looking for economic opportunities and/or security, or an opportunity to cross the border. However, before they can cross the border to reach Europe, they often find themselves in a difficult situation with limited mobility in Morocco. Since many of them have to walk everywhere, they often face road traffic dangers, such as car accidents.

There are few associations that try to support migrant children by paying for school fees, scholarships, materials and furniture to facilitate their learning in a conducive environment. However, the problem arises after the training – what should these children do next? Many of these children are from Sudan, Chad, Eritrea and Guinea, and thus (unlike Syrian children) do not have a residence permit. Therefore, they often cannot find work or secure a good internship, which really depresses the young adults and makes them psychologically fragile. That’s why youth on the move are forced to depend on the assistance of associations. This is a significant issue due to the short duration of these projects, which typically last one to three years at best.

As one testimony by J.O. (Nigerian national) illustrates:

“I have three daughters who all benefit from projects that assist children in attending school. However, despite this assistance, we struggle to make ends meet and cover all our expenses. Consequently, after school, my children go to the crossroads to beg. Sometimes, when the situation worsens, they skip school to help me.”

In Berkane, a rural town not far from Oujda, migrant children are often hired to work in the fields. This child labour is widespread because foreign children are easier to exploit and “cheaper” than Moroccan nationals. Their salary is often denied, there is no schooling and no training, and no associations to support these children.

3.5. Algeria

People walking to Assamaka, Niger after being expelled from Algeria. Source: Alarme Phone Sahara

At first glance, children on the move seem to be non-existent in Algeria. According to our contact from Ligue des Droits de l’Homme (LDH, Human Rights League), Oran:

“In recent years, the immigrant populations have been young men looking for work or in transit to Libya. As far as I know, there are no children.”

However, reality seems to be more complex. Further questioning of the same LDH comrade reveals that some children are visible in the public spaces: “They are aged one to twelve and part of begging networks. They are accompanied by parents or false parents [i.e. adults that declare themselves as a relative].” This information was confirmed by Algeria-Watch, especially in 2020, during the COVID pandemic.

In 2015, an article published in the national newspaper El Watan described the conditions of children on the move in Algiers. Many of them arrive on migration routes in alarming psychological states and have no choice but to live in squats. The article (reproduced in the French monthly Courrier international) focuses on the obstacles encountered by women on the move in terms of childbirth and education (access to healthcare, legal identity for the newborns and schooling).

Finally, the specificity of the situation of children on the move should be seen in relation to the specificity of Algeria’s anti-migration policy: the mass deportation policies at the Niger border, which have been going on for decades (for more details, see the previous analysis or directly the long list of reports produced by Alarm Phone Sahara); among the thousands of deportees are several hundred children who are later transferred to Agadez in order to be sent back to their country of origin in appalling conditions. An article from November 2023 by the Agadez media outlet Aïr Info closes with this analysis:

“The deportation of migrants to Agadez remains a major concern for the region in particular, and for Niger in general, which is reaping the consequences of the EU policy of externalising borders and all the mechanisms put in place to stop the phenomenon of irregular migration. All these mechanisms jeopardize respect for children’s rights, due to the inability of the state and its partners to provide them with effective care.”

Of course, many young Algerians are also leaving the country, many of them under 18 years old. However, it’s very hard to come by any information about their situation and struggle. According to our own observations as Alarm Phone, roughly one out of 15 people on the Algeria route are children.

3.6. Spain: the situation of migrant children on the peninsula

The situation of unaccompanied children on the move is one of the main concerns of civil society organisations at present. After the generalisation of the use of the category “MENA” in the public and media sphere has led to the dehumanisation and criminalisation of these children, we find it particularly important to talk about their situation.

Firstly, according to the data that we know of, and according to the Ministry of the Interior, 5,151 out of the 56,852 people who arrived in 2023 were under 18 years of age (9%). Since only 2,375 children arrived in 2022, it’s clear that more than twice as many children travelled in 2023 compared to 2022. Many of those children arrived in the Canary Islands (see section 3.1). According to data from the Observatorio Permanente de la Inmigracíon, as of October 2023 there were a total of 10,738 unaccompanied migrant children registered in the Spanish state, around 6% of whom were girls. The main nationality continues to be Moroccan, accounting for 68% of the group, followed by The Gambia, Algeria and Senegal.

The legal situation and rights of migrant children

According to the existing legal framework, unaccompanied migrant children and youth are entitled to the protection of the Spanish state under the same conditions as Spanish children, regardless of their place of birth and their administrative and documentary situation. Therefore, public administrations have the obligation to guarantee their welfare and access to basic rights, all of which are included in the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. All the rights that a child has in a situation of neglect by the Spanish state would also apply to a child with a foreign nationality, e.g. the right to care and accommodation, decent living conditions, education with equal opportunities, the right to be protected from tafficking networks and sexual exploitation.

In addition, migrant children and youth also have the right to seek asylum. In this case, it is important to point out that due to the situation of special vulnerability this right is protected not only by specific legislation on asylum (Law 5/1984 regulating the right to asylum and refugee status and its regulations, approved by Royal Decree 203/1995) but also by all regional, national and international legislation specifically aimed at protecting the rights of children. Lastly, it is also important to note that regional states in Spain are obliged to regularise the situation of children under their protection.

However, thanks to the tireless work of civil society organisation it has become crystal clear that there are great shortcomings when it comes to putting those legal guarantees into practice, especially in the area of reception and accommodation, age determination tests and irregularities in the recognition of documentation from certain countries, as in the case of The Gambia.

Violations of the fundamental rights of children

Regarding the care system, there are certain deficits in reception and accommodation, especially due to the lack of resources and political will to provide the necessary human and material resources to guarantee good accompaniment. There is an absolute lack of qualified staff in some centres, a lack of lawyers and, therefore, a latent gap in the transfer of social and legal information. Furthermore, there is no quality follow-up for young people who are expelled from the centres when they turn 18 or when a prosecutor’s declaration stipulates the age of majority. Civil society organisations are aware of cases of children who have left protection centres without any kind of referral to other social resources and without any regularisation process being activated.

When it comes to age determination tests, many organisations have been denouncing the racist nature of their essence and applicability, since the parameters for determining age were constructed on the basis of the white US-American population, which leads to possibly significant margins of error in the cases of children of other origins, especially from sub-Saharan Africa. These age determination tests consist of medical examinations that should be carried out with the foreign national’s “informed consent”. However, if the child does not consent to these tests, he or she will automatically be declared an adult by the public prosecutor. Medical examinations initially included an X-ray of the wrist, a dental examination, a genital examination and full nudity. In 2022, after the UN condemned this practice, a bill was passed to regulate the age assessment procedure, which includes a ban on tests requiring full nudity or genital inspections. Despite this progress, such tests continue to operate with significant margins of error that may determine the immediate future of many children (indeed an X-ray of the wrist is not reliable and the margin of error is 18 months). Yet, Law 26/2015 on the modification of the child and adolescent protection system, establishes that when the age of majority of a person cannot be established, they must be considered a child for the purposes set out in this law, until their age is determined.

Another of the current problematic issues has to do with the recognition of passports of children and the lack of access to rights that emerges from this situation. With the binding precedent of two Supreme Court rulings confirming the prohibition of age testing of children with passports, the reality is very different: There are many children expelled from the child protection system and condemned to the street due to the application of age tests to them when they are without a passport or even have a passport that stipulates their minority status. In the case of Gambian children, this scenario is particularly serious, as it entails a systematic and generalised policy of regarding passports as invalid due to an alleged open police investigation into document falsification that has not yet been proven, leaving many children and young people outside the protection system. As Alarm Phone, we find it shocking that children are placed under a general suspicion of lying, that they carry the burden of proving their age and that the deficits in their protection are horrendous.

4. Shipwrecks & missing people

A boat adrift that landed in Brazil. Source: AP Dakar

On 1 October, a shipwreck happens 42 miles southeast of the island of Lanzarote, Canary Islands. 45 people had been on the boat and seven remain missing.

On 6 October, Alarm Phone is informed about a boat that disappeared after leaving Morocco for the Canary Islands. The fate of the 60 passengers remains unclear.

On 8 October, Alarm Phone is informed about eight people missing after leaving Algeria towards the Spanish pensinsula five days earlier. Weeks later Alarm Phone finds out that the boat was rescued to Alicante, Spain. One person is missing. Another person is detained and accused of smuggling.

On 21 October, one person dies in the water off Cádiz, Spain when a boat left the people swimming to the coast. The other five people survive.

On 23 October, two boats with 203 people in total arrive at El Hierro, Canary Islands. One person didn’t survive.

On 26 October, a shipwreck happens off the coast of St. Louis, Senegal. Several people are reported missing. At least one person is found dead.

On 27 October, a boat with more than 200 people is rescued south of Tenerife, Canary Islands. One person is found dead and four people with serious health problems are brought to a hospital.

On 28 October, more than 20 people die during the crossing of a boat carrying more than 240 people from The Gambia towards the Canary Islands.

On 30 October, a boat with 209 people on board is rescued ~15 km south of Tenerife, Canary Islands. Two people are found dead.

On 31 October, a boat with 274 people on board is intercepted by the Moroccan authorities south of the city of Dakhla, Western Sahara. Two people are found dead. The boat had left six days earlier from Senegal to the Canary Islands.

On 4 November, Salvamento Maritimo reports that more than 500 people are rescued off the Canary Islands. Two people are found dead and two more die in the hospital.

On 5 November, 15 people die in a shipwreck off the coast of Mauritania. Several people are reported missing.

On 9 November, a boat with 81 people on board reaches El Hierro, Canary Islands. One person on board hasn’t survived the crossing.

On 4/5 November, Alarm Phone reports that several boats with between 803 and 856 Senegalese people drift to Mauritania. 13 people die aboard and 90-100 more people are estimated to have drowned. Many survivors are arrested and kept by the police, awaiting deportation. Soon after, Alarm Phone learns that another boat arrived in the Canary Islands with 80 survivors and 13 bodies. Six people are in a very bad state and are transferred to the hospital.

On 14 November, a person dies in a shipwreck off the coast of Motril, Spanish peninsula. 36 people survive the tragedy.

On 17 November, a boat with 45 on board capsizes off the coast of Guelmin, Morocco. Ten people are missing and 25 people die immediately.

On 22 November, a dead body is found off the Spanish enclave of Ceuta.

On 21 November, a dead body is found in the water and on 22 November, another dead body is floating off the beach of Águilas, Murcia, Spain. The cause of death has not yet been determined, but it can be assumed that it is two people who did not survive the crossing from North Africa to the Spanish peninsula.

On 29 November, two boats arrive in Spain with a total of 35 people on board. Four of them are cast into the sea and die before reaching land close to San Fernando, Cádiz, Spain. Eight others are cast ashore. They survive, but three of them are then hospitalised for hypothermia.

On 30 November, a boat about to capsize in rough sea conditions with 50 people on board is rescued by a merchant vessel 85 kilometres south of Gran Canaria, Canary Islands. One of them is already dead.

On 3 December, a person dies while crossing by boat to the Spanish mainland off the coast of Almería.

On 4 December, two bodies are found at Boudinar and Beni Ensar (Nador region) and transferred to the Hassani Hospital in Nador, Morocco.

On 20 December, four boats with 200 people on board are rescued close to Lanzarote, Canary Islands. The death of two people is confirmed.

On 20 December, a boat with 52 people on board is rescued south of Gran Canaria, Canary Islands. Two young people are found dead. They are identified as 19-year-old Bira T. and Djibril N., a child of age 10 to 12. The initial diagnosis in both cases is death due to hypothermia, which accords with the testimony of the other men who travelled in the boat. They report that they suffered from penetrating cold, strong wind and high waves.

On 23 December, a dead body is washed ashore at the port of Melilla, unidentifiable.

On 28 December, 14 people die in a shipwreck on the route to the Canary Islands. The rubber boat carrying 58 people sinks off the shores of Boujdour, Western Sahara.

On 30 December, four bodies of young Moroccan harraga are found close to Nador, Morocco.

On 1 January, a boat with 105 people on board is found by Salvamento Marítimo close to Gran Canaria, Canary Islands. Two of the passengers have died during the crossing and another one is in a serious health condition.

On 3 January, a dead body is found on the beach of Ceuta. It is assumed that the person died during the attempt to reach Ceuta by swimming from Morocco.

On 5 January, a corpse is found off Ceuta. The person was wearing a wetsuit and flippers, which seems to indicate that the person died in an attempt to swim to the Spanish coast.

On 7 January, a person is found drifting in waters on a truck tyre close to Fuerteventura. The survivor reports to the rescue assistance that he left Tarfaya on this tyre together with a friend, who died during the night.

On 15 January, a dead body is found close to the coast of Cádiz, Spain. Another person is reported missing. Only three people traveling on that boat can be rescued.

On 19 January, a person dies during the attempt to cross by swimming from a Moroccan beach to Ceuta.

On 24 January, a person drowns trying to reach the Spanish mainland by boat from Al Hoceima, Morocco.

On 26 January, a dead body is found on the beach of Ceuta. The person was wearing a neoprene suit, which suggests that the person tried to enter Ceuta by swimming.

On 26 January, a boat with 68 people is rescued close to El Hierro, Canary Islands. Two people on board are found dead.

On 27 January, another boat is detected close to El Hierro, Canary Islands. Three people haven’t survived the crossing.

On 5 February, a boat with 105 people on board gets into distress due to harsh conditions on the Canary route. When the boat is found close to Gran Canaria two people are dead and two more in serious health condition.

On 26 February, Marine Royale intercepts a boat with 122 people. One dead body is found on board.

On 27 February, a boat sets off from one of the beaches of Beni Sheker in unsuitable weather conditions and without any life vests, causing at least eight deaths when the boat capsized. Nine people are arrested, and a few bodies are washed ashore, but many of the almost 60 passengers remain missing.

On 27 February, at least 26 people die in a shipwreck along the Atlantic route north of Senegal. Testimonies report the presence of 200 or even more than 300 people on board. The number of missing people remains unclear. The tragedy occurs in St. Louis at the mouth of the Senegal River. One of the victims is the young man, Reda Al-Ghobashi.

On 4 March, a boat capsizes near Cape Verde. Five people die. Five survivors can be rescued but one of them dies in a hospital – bringing the number of victims to six. According to the four survivors, the boat left from a Mauritanian village carrying around 65 people.

On 4 March, one person dies in a hospital after being evacuated from the island of Alborán to Almeria, Spanish peninsula. Nearly 200 people from Morocco landed the week before on this military territory, which belongs to the Spanish state. Alarm Phone reported.

On 6 March, a boat is rescued close to El Hierro, Canary Islands. Of the 68 people on board, four people are dead and 14 are hospitalised with symptoms of hypothermia and dehydration, low level of consciousness, low blood pressure and wounds.

On 10 March, at least 76 people enter Ceuta by swimming and two over the fences: One person dies and one is missing.

On 12 March, Salvamento Marítimo rescues a boat with 40 people on board. Of these, two people are found dead. A merchant vessel had located the boat south of Gran Canaria, Canary Islands.

On 18 March, a floating corpse is found off the beach of the Spanish enclave of Melilla.

On 22 March, a shipwreck occurs off the coast of Motril, Spain. Two passengers are found alive, at least three people die and seven remain missing. According to the survivors there were 12 people on board when the boat left Algeria six days earlier.

On 23 March, a boat with 165 people heading to the Canary Islands is intercepted by the Moroccan Royal Navy. Four dead bodies are found on board.

5. CommemorAction – the fight continues

Demonstration in Ceuta on 6 February 2024, Source: A. Janda

In view of the countless deaths and the seemingly never-ending mourning for the thousands of people who have disappeared, drowned or been deported at the EU’s deadly borders, it is all the more important to create moments of solidarity and remembrance as well as spaces for our anger and condemnations. In this sense, 2024 is a special year: It marks the 10th anniversary of the Tarajal massacre.

Tarajal beach on 6 February 2024, Source: A. Janda

On 6 February 2014, the Guardia Civil shot at around 200 people who tried to swim from the Moroccan coast to the Tarajal beach in the Spanish enclave of Ceuta. Although the people were in distress, the Moroccan military presence failed to assist individuals who were drowning in their vicinity. The sad outcome of this atrocity: Fifteen bodies were discovered on the Spanish side, while numerous others went missing. Survivors were forcibly returned, and tragically, some perished on the Moroccan shore.

For over a decade now, survivors of this massacre have been fighting for justice. The violence exerted by the security forces and authorities “breached Spanish, European and international human rights law”, but all legal proceedings in this case were closed several times by the investigating judge in Ceuta. In July 2020, “the Audiencia Provincial in Cádiz confirmed the decision to close the case”, and in 2022, Spain’s Supreme Court finally closed the case – a decision which NGOs and relatives of those affected are currently trying to get revoked by filing complaints.

In the meantime, activists all over the world have been showing their support for the relatives and the survivors of this case. Especially in Spain, activists and NGOs have been annually organising the so-called “Marcha por la Dignidad” (march for dignity). This year, they showed their anger and power once more under the motto “XI MARCHA POR LA DIGNIDAD – 10 años exigiendo verdad, justicia y reparación” (10 years demanding truth, justice and restitution) by a demonstration throughout Ceuta to the beach of Tarajal, where the massacre took place.

Demonstration in Ceuta on 6 February 2024. Source: A. Janda

In memory of this massacre, every year there are also so-called CommemorActions organised decentrally on the 6th of February in numerous cities across Africa and Europe. The term CommemorAction is a fusion of “commemoration” and “action,” to emphasize “both the commitment to remembering those who died or disappeared in their pursuit of freedom of movement and the demand for justice”. In the same spirit as and strongly linked to the Marcha por la Dignidad, these events serve both as a means for mourning the deceased and to voice opposition against the EU border regime and the demand that it be held accountable. This year, hundreds of activists from various organisations came together to hold CommemorActions in 55 cities in 17 different countries.

CommemorAction MAP 2024, Source: Alarm Phone

Photos and video material about all these actions can be found here: https://commemoraction.net/photos-and-videos/2024-feb6/. From Amsterdam to Douala, from Dakar to Tripoli – the transborder network of solidarity showed once again this year on February 6 that remembering against forgetting is boundless. We will never forget, we will never forgive!