A collaborative report from Alarm Phone and LIMINAL

Key findings of the report

- There was no apparent rescue effort from the French side despite calls for help by phone and to French fishing vessels. Neither was a French boat escorting this dinghy, as is standard.

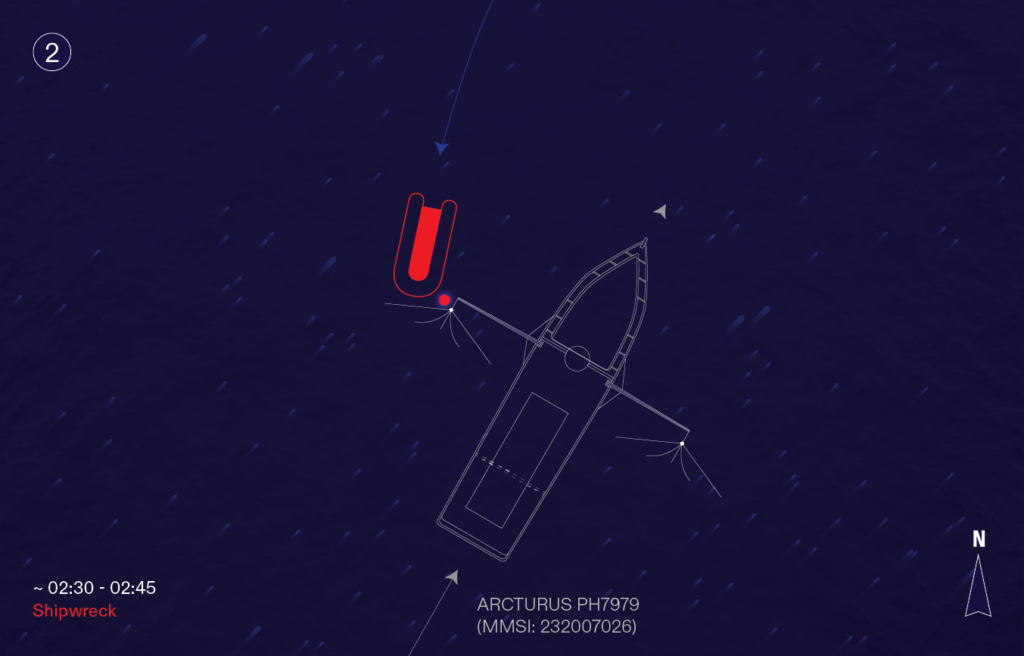

- The shipwreck occurred after the dinghy reached the British fishing vessel Arcturus. Beforehand the dinghy had been taking on water, but was still making way and able to navigate.

- The shipwreck occurred due to:

- people panicking and standing up inside the dinghy,

- metal and wooden boards damaging the dinghy’s floor.

- Arcturus’ crew initially rescued 11 swimmers who reached their vessel. Most people were still trapped inside the dinghy, which drifted away.

- During the subsequent rescue of those trapped in the wreck, Arcturus’ crew does not appear to have deployed life saving devices which people could have used to stay afloat whilst waiting for rescuers to get them out of the water. Such tactics were used by Border Force in a previous, nearly identical, situation where there was no loss of life.

- It also appears that Arcturus did not immediately communicate the severity of the shipwreck to Dover Coastguard nor issue a MAYDAY RELAY for the shipwrecked dinghy which likely delayed a mass casualty response.

- Such shipwrecks occurring at the moment of rescue, due to panics and surges onboard, are a known risk acknowledged in HM Coastguard’s standard operating procedures for rescuing migrant dinghies.

All the above elements highlight how such rescue operations are inherently dangerous and need to be carried out by highly trained crew. The shipwreck and subsequent loss of life occurring on the 14th of December was the result of many factors, for which no one can be individually held responsible.

Nevertheless, we suggest the UK government’s ‘stop the boats’ agenda, emphasising deterrence and criminalisation over rescue and protection, increases the likelihood of these deadly incidents.

Introduction: Unanswered questions

Many unanswered questions surround events from the 14th. Above all: who are the dead and missing? Almost one year on, there has not been any public statement made by authorities revealing their names. Neither has the exact number of people still missing been released. Without this information how can we collectively mourn or demand public accountability for their deaths at the border?

Our first report also raised questions of the coast guards on both sides: Why was this dinghy not accompanied by a French vessel, as is standard practice? Why the delay between the initial alert and launch of a search and rescue operation on the UK side? Despite all the surveillance trained upon French beaches and the Dover Straits, why does it seem this dinghy was unknown to authorities until the initial calls for help? What actually caused the dinghy to break apart and the people to enter the water? Is there any way the resultant deaths could have been prevented?

Unfortunately, many of these questions, especially those surrounding the search and rescue operation, are still unanswerable today. Our repeated requests to HM Coastguard under freedom of information laws for their records of the incident have been refused pending the publication of the Marine Accident Investigation Branch’s report. However, some facts have recently come to light through evidence given at the criminal trial of one teen-aged survivor believe to have been at the helm that night, and blamed for the deaths of other travellers. We have previously written about how the police and media are trying to make an example out of his prosecution, scapegoating him as a ‘criminal smuggler’ whilst other survivors have described him as just another passenger.

Members of Alarm Phone observed his trial and present here our key findings as to what caused the shipwreck. Our analysis is based on survivors’ testimonies, extracts of which are included in the text so as to highlight their voices and centre their experiences of that night. Our focus in this report is on the events surrounding the shipwreck itself rather than the subject of the criminal trial—whether or not immigration offences were committed, or the duress the driver was under after initially refusing to drive the boat and being ‘assaulted and threatened with death’.

Ignored calls for help

Our initial report stated the first call for help from the distressed dinghy came as a WhatsApp voice message and GPS position in French waters received by Utopia 56, a French association providing assistance to people crossing the border, shortly before 2am UK time. In this message R., a passenger of the boat who testified at the trial, said water was coming into the dinghy and they didn’t ‘have anything for rescue… for safety’. (During this message the dinghy’s motor could still be heard running in the background.) At 2:02 Utopia 56 telephoned to the French coast guard at Gris-Nez to alert them to the situation and pass the dinghy’s position. In his testimony R. told the court he also phoned directly to the French police, telling them: ‘we ran into trouble, water was increasing and we need urgent help‘.

Despite these calls for rescue, Automatic Identification System (AIS) data does not show a French rescue vessel being sent to assist the people. Instead, a French government press release states the rescue coordination centre at Gris-Nez asked a merchant vessel in the area to keep watch for the dinghy while liaising with Dover Coastguard about sending a UK lifeboat.

Without any rescue vessel nearby, multiple survivors testified they looked towards the nearby fishing boats which they could see for help. The driver steered towards the closest one, but it did not help.

‘This fishing boat, we thought we could approach them… They were French fishermen and they didn’t come to our rescue…’ (Y. from Afghanistan)

‘We were screaming and shouting and saying that we are going down. We kept screaming and asking for help, help help. They were coming and looking and saying no and going away.’ (Y.)

Refused help by the first boat, the dinghy continued towards another.

‘Further in the distance there was another boat, so we tried to go there. We were shouting out but there was no answer or reply coming back from the other boat.’ (W. from Afghanistan)

This next boat the dinghy came to was the Arcturus. At the time it was fishing for scallops in UK waters, but as they approached it seems the crew either did not notice or ignored the people.

‘When we got closer near that boat, I think they were busy catching fish.’ (W.)

‘We were getting closer to the fishermen, they were catching fish. We were screaming and shouting, they ignored us initially, until we got close enough.’ (Y.)

The trouble getting the fishermen’s attention on Arcturus caused the people in the dinghy to become increasingly distressed to the point some took matters into their own hands to get rescued.

People were happy first that they would help us but no action, screaming and shouting, eventually people started jumping in the water. (D. from Afghanistan)

At first one man jumped out of the dinghy and swam towards the fishing boat. He grabbed hold of the fishing gear that was lowered into the water which ‘made the fishermen take notice of us, because the boat was shaking’ (Y.).

One of the guys managed to get to the other boat. He was screaming but there was no reply. Finally someone came. (W.)

The swimmer had gotten the attention of the Arcturus‘ crew, but the other travellers stayed on the dinghy. Water was coming inside, but the craft itself was intact. This was all about to change.

Panic onboard: the dinghy shipwrecks

From the testimonies it appears that as the swimmer reached Arcturus, the dinghy continued approaching the fishing boat so that everyone else could be rescued. However, once the dinghy reached Arcturus, it was not immediately clear if and how the fishing boat would rescue them.

‘They said they don’t know how to get us out of the water. They said they would call for help from the police. They pulled the man from the chains onto the deck. There were 45 of us still on the boat.‘ (Y.)

‘They didn’t take people on, said they will call the police’ (D.)

This hesitance and confusion caused those in the dinghy to become increasingly desperate to get themselves rescued, and testimonies describe everyone standing up to better get the attention of the Arcturus‘ crew or to try and climb onboard.

‘At that point, everyone stood up and they wanted to rush to rescue themselves to go to the fishing boat.’ (Y.)

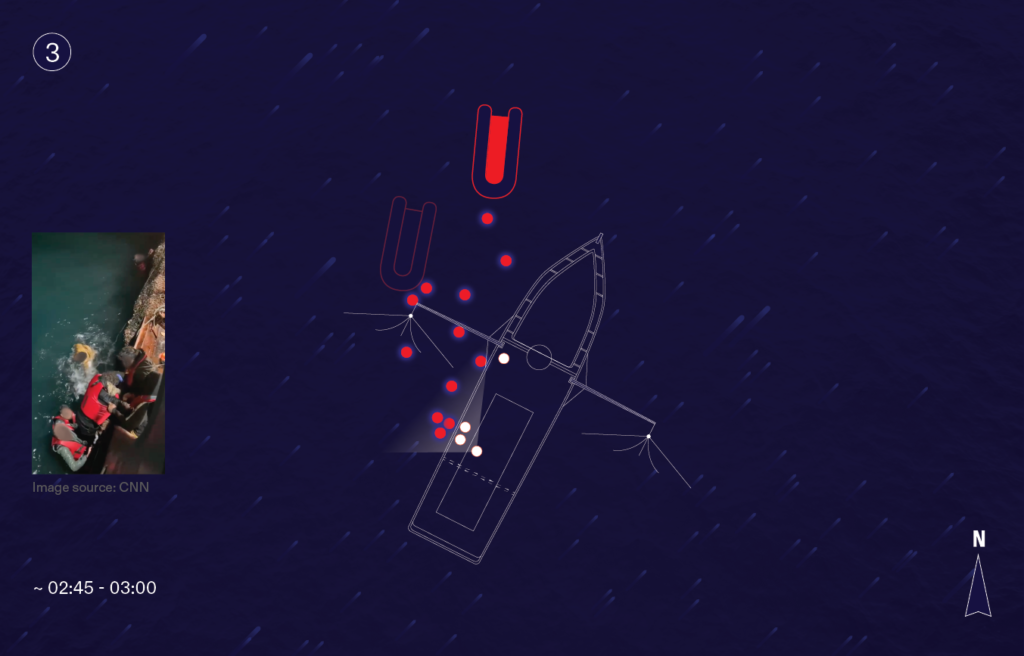

This standing up and rushing to rescue themselves proved to have drastic consequences for the dinghy, and all testimonies describe the shipwreck occurring as a result.

‘We were shouting out but there was no answer or reply coming back from the other boat. … at this point there was a bursting noise of the boat breaking apart, then we started screaming.’ (W.)

People were shouting and they were screaming and they were moving, at that moment the boat broke. (F. from Afghanistan)

‘Everyone started to stand up. As soon as they stood up the floor gave way. If I had kept sitting down they would have crushed me.’ (W.)

As they stood up the full weight of the approximately 45 people on board shifted solely onto the floor of the dinghy. Beforehand people had also been sitting along the sponsons, with the weight spread more evenly.

The weight of the people on the floor does not seem to have been the only factor contributing to the shipwreck.

Metal and wooden boards laid on the dinghy’s floor. While installed in an attempt to provide the dinghy’s bottom more support, the sharp edges of the boards to pierce the rubber. Together the weight, movements of the people and the boards along the floor ripped the dinghy’s bottom out from underneath the people. Very quickly everyone ended up in the water and a dangerous situation became deadly.

With the floor having disappeared beneath them, most of the people became trapped within the sponsons.

The boat collapsed into itself. Some of us didn’t have any life vests or equipment to keep them afloat. Because the boat collapsed into itself, dropping some of the people, some were trapped inside. Some managed to get out, and some of them were inside the boat. (Y.)

People tried to stay afloat by clinging or climbing onto the wreckage of the dinghy.

‘Everyone stood up and the boat fell apart, so what happened was the bottom of the boat fell apart, the round part of the boat the sides that were inflated remained and everyone had to hold onto this.’ (D.)

However, not everyone was able to get out of the cold water. The court heard ‘a deceased male was found in the wreck of the inflatable’. Those who did get out of the wreckage swam to the Arcturus and climbed onto its fishing nets which had been hauled up.

‘Some people were swimming and trying to get to the fishing boat, to hold onto something to pull themselves up. Others were still struggling. We were in the water for about 30 minutes. Some of the people who managed to get to the fishing boat, they sent out for them ropes for them to hold on to. We saw bodies beneath us.’ (Y.)

The ‘rescue’: further questions

Many survivor testimonies raise questions about the immediate reaction of the Arcturus‘ crew to the shipwreck: who they focused on rescuing in the first instance, why they did not deploy more life-saving flotation devices, when they radioed for help, and why taking photographs seemed such a priority?

After the shipwreck it appears Arcturus initially prioritised bringing those who swam to their boat onboard, whilst the dinghy itself, with most of the people still trapped inside, drifted away.

‘At first our boat was very close to the fishing boat then the boat broke and the waves pushed the boat away’ (F. from Afghanistan)

The skipper of Arcturus testified that after the shipwreck the ‘boat was still underway doing about 2 knots, dinghy drifted but [we] had 5 or 6 people on board, then more people started swimming towards the boat and then after we had 11 on board [we] lost sight of dinghy. Once we had 11 people on board, me and crew listened for screams and shouts for help so steered towards the screaming and found dinghy in dark ahead.’

The Arcturus then came alongside it for a second time, and the crew began working to get the rest of the people out from inside the wreck. This was an arduous process given the high freeboard of the trawler and the few ropes available to help people up with. Videos taken by Arcturus‘ skipper, and published by corporate media outlets, show the severe difficulty people in the water had getting on the trawler.

We were in the water for over half an hour. Myself, I was in the water for 15 mins, but there were other people still in the water. We were shivering it was so cold. (W)

Instead of deploying life-rafts or personal flotation devices, the skipper of Arcturus testified that one of his initial priorities was to film and take photographs of the situation. This is something he had done previously when encountering migrants in the Channel, shown during an interview he gave to GB News in which he also criticised the UK government’s ‘migrant taxi service’. Given the dire circumstances, with dozens of people in the water alongside his vessel, his decision in hindsight appears questionable if not negligent.

‘They initially didn’t help, they just took pictures for the police. […] At first they [were] dismissive, but after they took photos they helped.’ (W.)

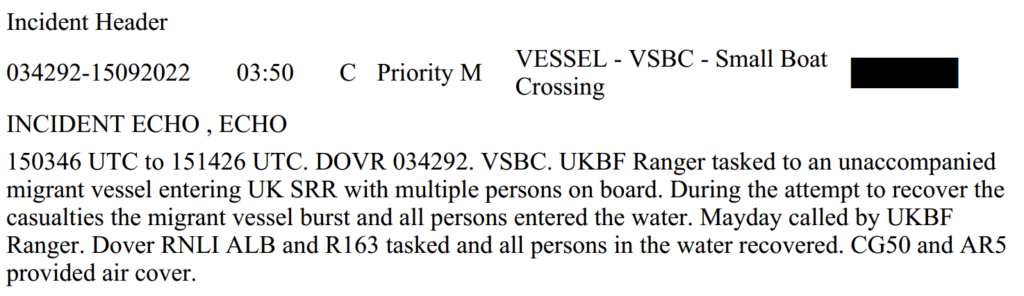

A similar case involving a Border Force vessel, but no loss of life

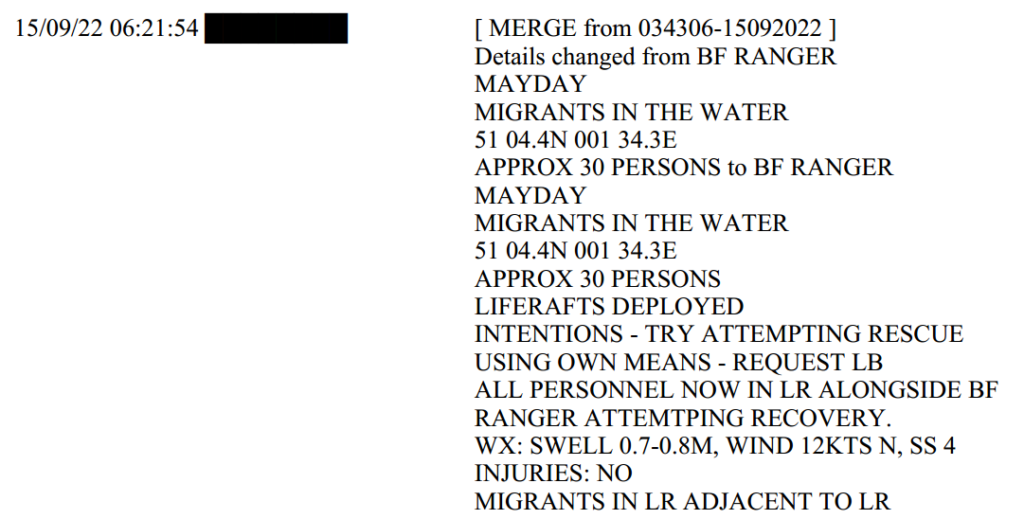

It is important to briefly highlight a nearly identical situation a few months prior which had a very different outcome due to the actions of the rescuing boat’s crew. Alarm Phone obtained HM Coastguard’s log from an incident in September 2022 where ‘during the attempt to recover the casualties the migrant vessel burst and all persons entered the water’, excerpts of which have been reproduced below.

In this case, everyone was safely recovered despite the shipwreck because it appears the crew of the Border Force vessel immediately deployed their own life-rafts to help the people in the water stay afloat first. This meant the survivors could float while waiting for rescue rather than struggle to keep their heads above water. Similar actions being taken on the 14 December by the Arcturus‘ crew may have improved the chances of some of those who died.

‘These poor people who didn’t have a jacket on, they have given their lives. I had a jacket on. My jacket wasn’t working properly because water was in my clothes. I was getting submerged.’ (W.)

What did Arcturus tell the Coastguard?

There are also questions regarding what Arcturus communicated to Dover Coastguard as the incident was unfolding. The skipper testified that after being awoken by his watch keeper around 2:30, and hearing shouts of ‘help!’, his first actions were to raise his fishing gear and call the Coastguard. However, when he is later asked if the Coastguard had already been radioed after the 11 people were brought onboard and the dinghy was drifting away, he replies ‘I can’t remember.’ In his summing up for the jury, the Judge only says that Dover Coastguard received a radio message from Arcturus at 3:03, more than half an hour after the skipper reported being awake and aware of people in the water. The judge also states Arcturus’ skipper ‘took a number of photographs between 2:55 and 3:20 in the morning’. The timing of these photographs compared to the reported call to Dover Coastguard again evidences the skipper’s prioritising filming over rescue.

According to @outonashout the Royal National Lifeboat Institution’s (RNLI) Dungeness lifeboat was first paged around 2.20am. This is also before any mention of a radio call from Arcturus, indicating the lifeboat likely launched solely on the information Dover Coastguard received from Gris-Nez at 2:13. Dungeness Lifeboat may not have known it was on its way to a shipwreck at this time. Dover RNLI Lifeboat was then paged around 3:05 and Ramsgate around 3:25. ADS-B flight data shows the Coastguard’s rescue helicopter was airborne from Lydd by 3:15. The commander of the HMS Severn was awoken and informed of people in the water at 3:17. The Prefecture Maritime’s press release states that Dover Coastguard put out a MAYDAY RELAY message for a shipwrecked dinghy with people in the water at 03:21. (A MAYDAY RELAY from Arcturus, which international regulations require all vessels to issue when they witness another vessel in distress which cannot transmit a distress message itself, is never mentioned in the press release nor testimonies.) All these actions took place before Dungeness Lifeboat arrived on-scene at 3:30, implying Dover Coastguard received further information about the shipwreck from a different source, likely Arcturus’ message at 3:03.

It is reasonable to suspect that Dover Coastguard tasked all the additional assets as soon as it knew the full extent of the situation with the shipwrecked dinghy and multiple people in the water. If this is true though we must ask why the significant delay between when Arcturus‘ skipper reported being aware of people in the water at 2:30, and the launch of Dover Lifeboat and the Coastguard helicopter after 3am? With the Coastguard’s logs still not released this question, for the moment, remains unanswered.

Nevertheless, 31 of the estimated 48 people onboard the dinghy were rescued by the Arcturus’ crew. People were able to scramble onto the fishing nets to get themselves out of the water, and the crew used ropes and the ship’s boarding ladder to help others climb onboard. From 3:30 other rescue assets began arriving on-scene and helped get the rest of the people out of the water. In total 39 people were rescued by the Arcturus, RNLI lifeboats, the Coastguard helicopter, and the Royal Navy cutter HMS Severn. However, the fact remains four people lost their lives and we estimate another five are still missing at sea as a direct result of the dinghy shipwrecking.

The missing

Still no official information regarding the exact number of people missing has been released. Survivor testimonies state there were between 46 and 48 people on the boat. With 39 rescued, and four confirmed dead, three to five people are still missing at sea, about whom hardly anything is known. One of the survivor’s testimonies suggests that four may be Afghan:

‘we counted all the Afghans, some were accounted for, I think four still missing’ (Y.)

Disturbingly, it seems one man was left by the crew of the Arcturus in an unknown state, and his body was never recovered. The skipper testified that when Arcturus left the scene of the shipwreck for Dover they discovered someone tied to the boat by a rope (a distressing photograph of whom, also taken by Arcturus’ skipper, has been published by a corporate news network): ‘one of my crew said there’s a rope tight here, so I pulled it up and there was a body attached to the rope.’

When pressed as to whether the man was deceased or if he disappeared into the water, the skipper replied:

‘Not straight away. [I] called HMS Severn for help, told my crew to get him on the boat. They didn’t want to touch a dead body so called Severn to help us out to get hold of the body but they were quite busy and by the time it got to us the body had got untied.’

While we still do not know who this person was, the fact that his body was simply left to come untied and sink into the sea because the Arcturus’ crew did not want to touch a body they presumed to be dead points perhaps to an overall attitude of indifference towards the shipwreck victims that night which may have played a role in determining their (in)actions: from initially hesitating to provide assistance, to prioritising taking photographs over rescue to not deploying the boat’s life-saving devices.

Conclusions: lessons learned

Some have compared the 14 December shipwreck to that of 24 November 2021 to point to lessons which seem to have been learned. Indeed, it appears that Dover Coastguard took a clear decision to task all available assets to the rescue once it knew of the shipwreck despite the Arcturus‘ position very near to the border of French waters rather than try to ‘pass the buck’ to the French. There are, however, other lessons which should have already been learnt, and which may have prevented loss of life that night.

We have already mentioned the successful use of life rafts in a previous case where a dinghy broke apart alongside a Border Force boat. However, other actions may have perhaps avoided the shipwreck altogether. Unlike in 2021, on 14 December it is clear the dinghy did not shipwreck by itself in the middle of the sea but through its interaction with the Arcturus. As Alarm Phone we know from handling many distress calls and speaking with both rescuers and rescued that safely rescuing an overcrowded rubber boat is an extremely challenging task, even for trained and experienced search and rescue crews with boats better designed for the task than a fishing trawler. The actual moment of rescue can be the most dangerous. People who are scared and who have been packed tightly together for hours already can behave erratically when first presented with an opportunity to escape their situation. Individuals are not able to control their own movements as they are pushed or have nowhere to go, and panic quickly spreads.

The UK Coastguard’s standard operating procedures for ‘SAR Incidents Involving Migrants’ from August 2022 clearly shows the risk of a capsize at the moment of rescue to be well-known. That document states: ‘Any declared assets responding are to stand off from the vessel… This will also avoid a migrant surge and potential capsize.’

From the testimonies we witnessed it appears the initial hesitancy on the part of the Arcturus‘ crew, and the collective actions of the people in the dinghy to try and get rescued, created a panicked situation onboard which led to the floor giving way and everyone entering the water. This begs the question: what if the dinghy had been in the company of a French rescue boat so that people did not feel as if they had to ‘rescue themselves’ or was reached first by an experienced lifeboat crew capable of managing volatile situations to avoid panic and shipwreck? Additionally, why was there apparently no airbourne surveillance of the Channel that night, despite the high probability of crossings?

Despite trying to understand what happened in order to learn how such shipwrecks can be prevented in future, our intention has not been to criticise the efforts of the rescuers involved. The fact is that given all of the factors involved in the shipwreck which unfolded dynamically, it is not possible to blame any one individual for the deaths that night. This is, however, exactly what the UK government is trying to do. In order to appear tough on ‘smuggling gangs’ and resolute in its pledge to ‘stop the boats’, a teenaged survivor is facing life in prison accused of four counts of manslaughter and facilitating a breach of immigration laws. As the first jury was unable to reach a verdict, he will face a second jury trial over the winter. He continues to remain in prison on remand.

We can, in the meantime, pass judgement on the UK’s border regime which forces people into taking such dangerous and unnecessary journeys, and which is ultimately responsible for the deaths and disappearances from 14 December. With no other way to claim asylum (which everyone in the dinghy did) than by first arriving in the country through illegalised routes, people are being forced to take huge risks to paradoxically live in safety. Despite all the money, technology, surveillance and resources directed towards the UK government’s ‘small boats operations’ in recent years, it still appears a matter of luck whether or not people get detected, accompanied and rescued by competent actors, or left to chance encounters with inexperienced rescuers. Furthermore, we can lay blame on years of racist rhetoric demonising people crossing the Channel on small boats in the name of ‘hostility’ and ‘deterrence’. Deaths at sea are acceptable to the UK government as a necessary part of its deterrence agenda, despite not actually deterring anyone. Preventing these deaths could be easily accomplished by simply allowing people to make their journeys on the ferries. By choosing to deny them this route, it is the UK government which is guilty of causing people to die and go missing at sea.