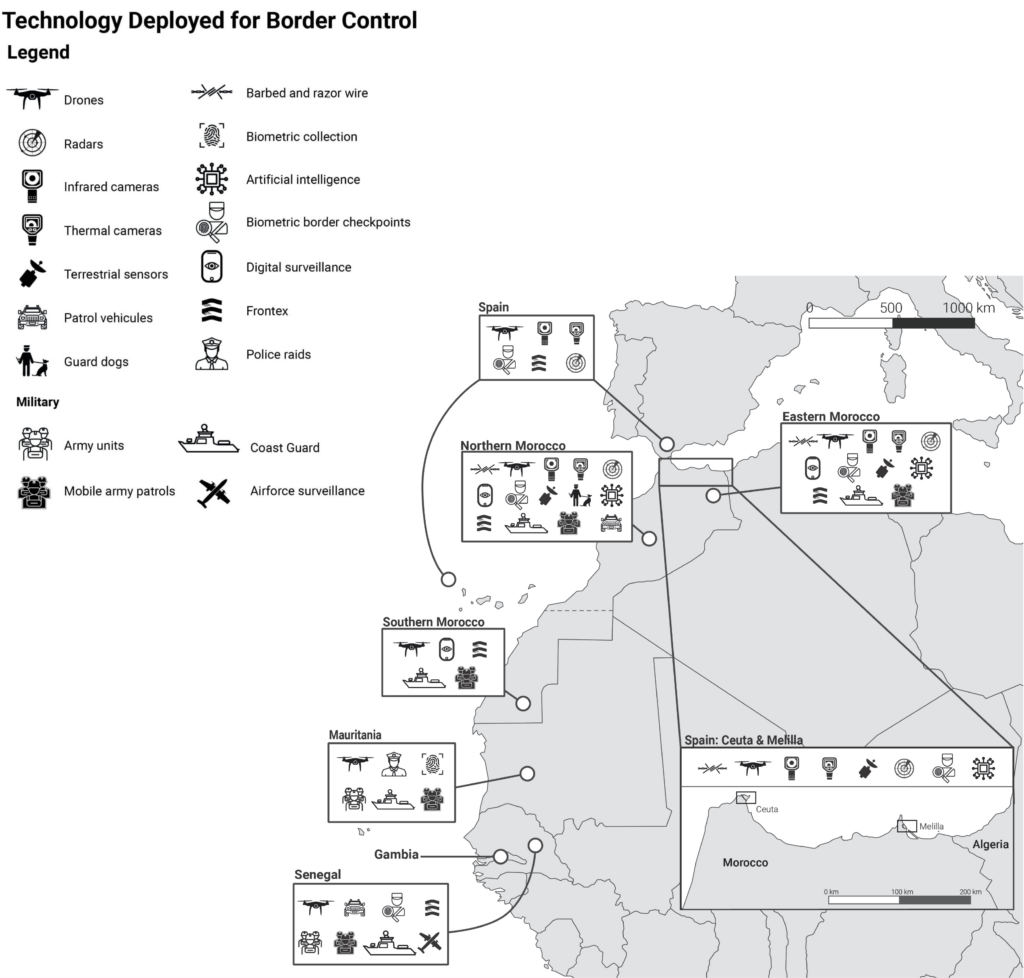

Map 1: Technology deployed for border control. Source: Alarm Phone

1. Introduction

The concept of insecurity, closely linked to the political instrumentalization of fear, has been used by institutions and politicians for decades to establish policies to control populations considered undesirable and criminal. Since the 1990s, a European space of ‘freedom, security and justice’ has been established, which is in reality based on a political project of insecurity, in which people considered to be threats are put at risk through a series of control mechanisms and increasing militarization. The new European Pact on Migration and Asylum (see report), adopted on 10 April 2024, reinforces this logic with a set of reforms that extend the criminalization and digital surveillance of migrants.

In response to this racist narrative of insecurity brought about by migration, the concepts of security and safety are then linked to policies of militarization and increased border surveillance.

Security encompasses more than weapons and control and surveillance technologies. It is an entire system which includes legal norms and tools (bilateral readmission agreements, the visa system): so-called ‘development’ cooperation policies – that in reality disguise police cooperation aimed at controlling mobility – repressive practices such as mass deportations to the desert, widespread profiling and numerous places of detention along the migratory routes.

However, in this report, we focus on the materialization of borders through the technologies used to detect, track, target, injure and even kill people on the move, as well as on the financing of these technologies. Some of these technologies make the border visible: vehicles, drones, weapons, radars, razor wire. But the increasing outsourcing of migration control with the transfer of border management to third countries and the establishment of smart borders can also create the illusion, from within Europe, that borders are partially invisible.

Any discussion about “securing” migration routes must be part of a broader analysis of the expansion of militarism in the world and in the region. The conflation of war/terrorism and migration allows states to use institutions and tools designed for war to control mobility. This is how the continuing military and police cooperation between the EU and African states, complicit in systematic human rights violations, is justified in a colonial continuity. After independence, the borders inherited from colonization were poorly controlled. During the 1980s and 2000s, the conflict over Sahara and the Senegalese-Mauritanian crisis led to an initial militarization of the borders. Since the 2000s, the jihadist threat has justified a strengthening of borders with international assistance (France, EU, USA). For 20 years, “the fight against human trafficking” has played a major role in justifying the militarization of borders. And we now see that “human trafficking” and “terrorism” are being lumped together by the EU and the states in the region under the heading of “transnational crime” (2012 transnational crime = terrorism) (2025 agreement with Senegal cross-border crime = human trafficking). The European Union and some of its member states are spending billions of euros to transfer border surveillance and control capabilities to foreign countries in order to prevent migration to their countries. Frontex and the coast guards are playing an increasingly important role in these projects, as they can decide which areas and technologies to study and finance if they identify an operational gap. The migration control industry is thus becoming not only a deadly business for people on the move, but also a thriving business for European companies and the imperialist industry that profit from this constantly expanding deadly market.

This approach to securing migration routes puts people on the move at increasing risk. In this report, we strongly criticize this use of the concept of security and call for a reversal: we must recognize the insecurity that control and surveillance technologies create for people on the move and call for the securing of migration routes to enable freedom of movement for all who wish to exercise it.

In this report, we document how the borders are made more and more insecure through control and repression technologies in the Western Mediterranean and the Atlantic route.

In the chapter about statistics (2.) it becomes clearly visible that the rising numbers of sea crossings and deaths at sea are a direct deadly consequence of the border militarization and EU security policies that force people onto more and more dangerous routes. The different regional contexts of Morroco (3.1), Senegal (3.3), Spain and the Canary Islands (3.4), with an in-depth look at Mauritania (3.2), show how the securitization of migration has been a political priority for several years, often driven by EU funding. The last part about shipwrecks and missing people (4.) is about remembrance and grief in our struggle again murderous border regimes.

|

Disclaimer on our terminology Our report draws from different sources. We gather information as people reach out to us via the Alarm Phone number. Various local Alarm Phone (AP) groups in the region document their observations and information on the site. We are aware that we do not have a complete overview of what is happening on the Western Mediterranean and Atlantic routes. Whenever we could, we linked to sources in newspapers and other articles. But not everything we report on is documented in the media. All information without reference stems from activists in the regions. Alarm Phone is a network of volunteer activists. The bulk of Alarm Phone members in the Western Med and Atlantic region are West African or European in origin. As a consequence, we are much more embedded within the communities of people on the move from West African countries than we are from the Harraga communities of the Maghreb. This inevitably leads to an underrepresentation of the experiences of the latter group. The only way to rectify this problem is to expand what we do and work to build a truly transnational community of resistance. This is slow and laborious work, but we are committed to doing it. The language that we use is important. The words that we use also carry the weight of their history, and that is a history of power. We constantly struggle to view the world correctly and to find the right descripition of what we see. There is no single viewpoint that will encompass everything. To see the world correctly, we need a kaleidoscopic view. This report is a collective endeavour. Many of the authors are not writing in their first language, and most of the witness testimony is also given in a second or third language. We consider this a strength. We do not wish to regiment the language used in our descriptions of people and their backgrounds. Where someone might baulk at ‘sub-Saharan’ as implying inferiority and prefer ‘Black’ or ‘Black African’, another might reject the racialization implicit in the latter terms. Likewise, some of us avoid talking of ‘migrants’ and prefer to emphasize personhood with ‘people on the move’, but for others of us this language is fussy and unnatural and we are proud to be migrants. We have left, as much as possible, the authors’ different choices of description, especially where the author is herself a person on the move. |

2. Sea crossings & statistics

The deadly consequences of Europe’s militarized border regime are clearly visible in the numbers and statistics of sea crossings. The EU’s surveillance technologies, financing of Frontex or coast guards, the outsourcing of violence to third states, this all forces people onto ever more dangerous routes. The result is not fewer departures, but more interceptions, more disappearances, and more death at sea.

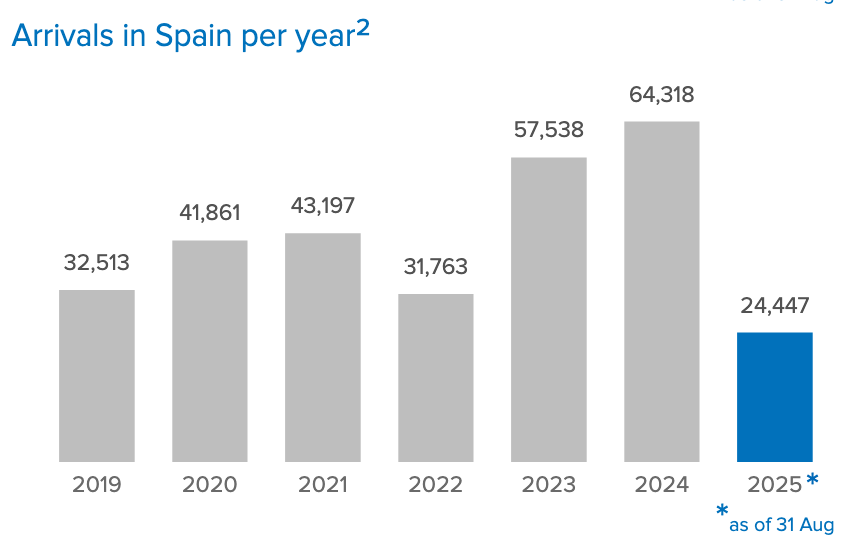

According to UNHCR, 24,447 people arrived in Spain between January and the end of August 2025. Compared to the same period last year, this represents a significant decrease in arrivals to the Spanish state. But fewer arrivals do not mean fewer journeys. On the contrary: Alarm Phone data shows that almost the same number of boats left this year as last year. Boats continue to depart in similar numbers, yet they are systematically intercepted, pushed back, or vanish without trace. The EU presents declining arrival figures as a success—when in reality they signal the brutal effectiveness of a system designed to stop people at any cost, even at the price of mass death.

Figure 1: Arrivals in Spain per year. Source: UNHCR SPAIN Weekly snapshot – Week 35 (25 – 31 Aug 2025)

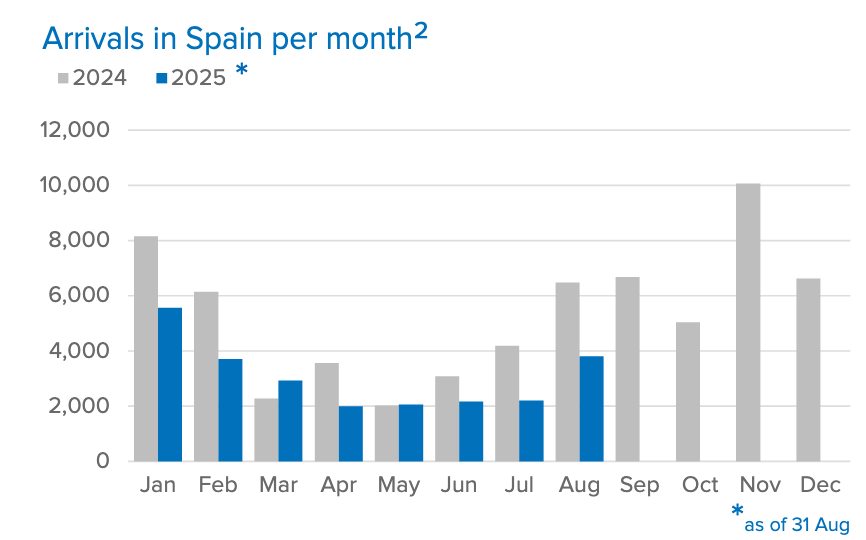

Figure 2: Arrivals to Spain per month. Source: UNHCR SPAIN Weekly snapshot – Week 35 (25 – 31 Aug 2025)

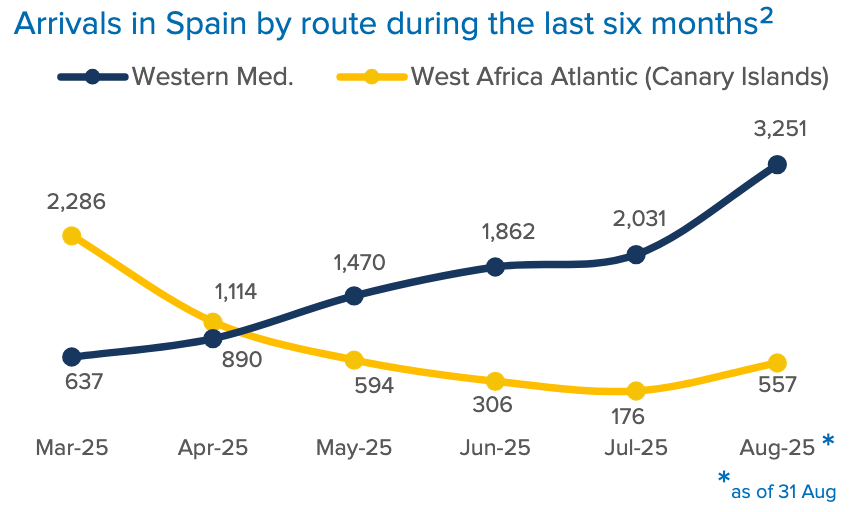

Between the beginning of March and the end of August 2025, Alarm Phone was directly involved in 55 distress cases along the Western Mediterranean and Atlantic routes, assisting at least 1,941 people. The reported increase in boats departing from Algeria (Alarm Phone reported) continued, departures from Algeria surged: 29 boats left, more than from any other region. By contrast, only 20 cases were recorded on the Atlantic route, confirming UNHCR’s observation of fewer arrivals via the Canary Islands compared to the record highs of last year.

Figure 3: Arrivals to Spain by route. Source: UNHCR SPAIN Weekly snapshot – Week 35 (25 – 31 Aug 2025)

AP also documented two cases in the Alboran Sea, two in the Strait of Gibraltar, and two land cases toward Ceuta or Melilla. In two cases, relatives searched for missing loved ones; however, the point of departure remained unknown.

Unfortunately, too often we have to close a case without knowing the fate of the people. In the period covering this analysis, we had to do so in 22 Alarm Phone cases, mostly the ones that departed from Algeria (see for example one of the seven Algeria cases Alarm Phone was alerted to in May). Altogether, this refers to a minimum of 364 people. In the majority of the cases we do, however, know the outcome: In the last seven months, nine boats got intercepted by the Marine Royale or other coast guards. sometimes these violations of the freedom of movement were supported by merchant vessels. Two boats returned on their own or with the help of fishermen. And while we are happy to confirm that twelve boats were rescued by Salvamento Marítimo and three boats arrived autonomously to European shore, we are very saddened to report one boat which shipwrecked entirely in the Atlantic. The boat with 140-150 passengers capsized off the coast of Mauritania, near Mhaijratt. Only 16 people survived.

Including this catastrophic case, the violence of Europe’s borders in the Western Mediterranean and Atlantic killed at least 135 people during the spring and summer of 2025, including a pregnant woman whose baby did not survive. At least 46 people remain missing on their way to Spain. These figures refer to our own statistics, but of course many more people died and went missing in cases in which Alarm Phone was not directly involved (see Chapter 4 of this analysis).

3. Border regimes in the different regions

3.1. Morocco

As a key player in the externalisation of the European Union’s borders, Morocco manages migration security through enhanced technological surveillance and military and police cooperation, particularly with Spain. Human rights violations committed by this ‘partner’ country against migrants enjoy total impunity from European institutions.

As part of the EU-Morocco Cooperation Programme launched in 2023, €152 million has been earmarked specifically for migration:

“strengthening border management, combating migrant smuggling networks, national immigration and asylum strategy, voluntary returns and reintegration in accordance with human rights”.

Strengthening the so-called “fight against irregular immigration” is a central component of this partnership.

The Moroccan migration control system, developed with financial, logistical and political support from the EU and certain member states, includes video surveillance, radars, drones and ground sensors, particularly around Ceuta and Melilla, and the integration of infrared and thermal detection technologies in areas considered “sensitive”, such as the Sahara.

Biometric databases (fingerprinting and facial recognition) are another major element of migration control. The land borders between Morocco and Spain at Ceuta and Melilla have undergone major restructuring involving significant technological investments as part of the European Union’s “Smart Borders” project, notably through the introduction of the EES (Entry/Exit System), which records the entry and exit data of non-EU travellers in these databases.

Spain is the EU country that invests the most in outsourcing its border control to Morocco. In December 2024, 20 video surveillance systems, worth €4.1 million, were supplied by Spain for the management of Morocco’s borders. In January 2025, vehicles and equipment (motorcycles, trucks, all-terrain vehicles, thermal cameras, night vision equipment) worth €2.5 million were delivered to Morocco by Spain.

Morocco is also planning to become a producer of military drones through a partnership with Israel (BlueBird Aero Systems). At the same time, negotiations are underway to acquire American Sea Guardian (MQ-9B) drones. Border surveillance is not the only purpose for which drones are used. The conflict in the Sahara is also a major factor in Morocco’s desire to develop this technology on a military scale (see section 3.1.3 on Southern Morocco).

3.1.1. North Morocco

In the north of Morocco, the most visible manifestations of the border are the physical barriers that separate the Spanish enclaves and Morocco. At each beach in Tangier and in the forest, which acts as the last stop for people on the move trying to reach Europe by boat, there are heavy-handed police patrols. Alarm Phone activists in Tangier recently learned of a young Senegalese who was killed by a dog used by Moroccan security forces in the forest. This security presence has made it almost impossible to reach Europe from Tangier, with security forces in the region very well equipped with sophisticated technology thanks to enormous financing from the EU.

The actors implicated in the security of the border are diverse and far-reaching. Moroccan auxilliary forces, coast guards, train and road guards and even more insidious actors such as secret services cooperate to surveil and control people’s movement. There are also the interior ministry, the department of customs, the Guardia Civil, international actors such as the World Customs Organization (WCO) and the private sector working together to surveil and securitize.

Many tools are used to support the border infrastructure, from drones and cameras for beach surveillance and detention of those suspected of driving boats, to less visible digital surveillance systems to enhance border security. There is for example software to monitor data, communication interception devices, AI that analyses data traffic and tracks communication across different applications such as WhatsApp in order to track and surveil individuals. One of our Alarm Phone comrades reflects this development in the use of digital surveillance:

“I remember that time when there was a massive influx of migrants, Moroccans. There were messages sent on social media saying that the Northern borders, between Tangier and Nador, were open, that people could cross. And so there were a lot of young people, Moroccan minors, who went to try their luck. So the people who were behind those messages were all arrested. The authorities managed to identify them on social media. Because in Morocco, there is an IT monitoring service made up of very skilled people, young people who work solely for that purpose. […] There’s a monitoring service that’s very powerful. And that’s new, too. A few years ago, it wasn’t very important, it was used much more in the fight against terrorism, to detect people. Now they’ve brought it back into the context of migration.”

While private companies are not officially involved in border surveillance, it is suspected their role is hidden in indirect contracts for states’ border security. With regard to the financing of border infrastructure in the north of Morocco, this is largely from the EU and Spain. With the increased funding of Frontex by EU states since its establishment in 2004, its capacity to support border militarization has also increased.

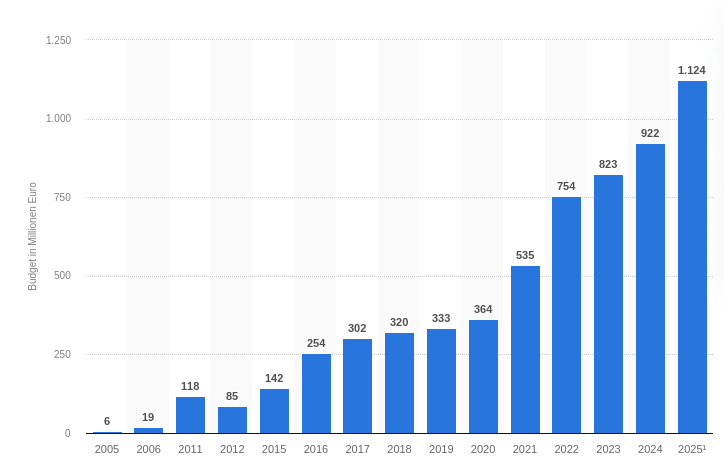

Figure 4: Budget of the European Border and Coast Guard Agency (Frontex) from 2005 to 2025 (in millions of euros). Source: Statista

Closing and controlling the border has a catastrophic impact for people on the move in the north of Morocco, particularly for Subsaharan Africans. Most people on the move arrive in Morocco with the plan to reach Europe and find a better life for themselves and their families, but since 2018 it has been practically impossible to succeed. Many have difficulty finding work in Tangier and resort to begging to survive, which is treated harshly by the police, or informal and exploitative domestic work. Consequently, there have been many ‘voluntary returns’ via IOM in recent years. For those who stay or cannot return to their countries of origin, they can only save their money and try again. Violent arrests and traumatizing experiences with the police result in severe depression and many young people developing drug and alcohol addictions.

Despite the border securization, people persist in trying to reach Europe. There are very few successful departures in the north because of the enormous level of security, and consequently it is very visible that departures are being displaced south, from as far south as Guinea or Gambia. These journeys are very dangerous and long, perhaps weeks at sea. The increasing presence of Frontex in West Africa is further evidence of the externalization of European borders further south.

The border in Tangier has been increasingly militarized since the early 2000s as Europe has sought to externalize and reinforce its border regime. The Ceuta barrier, initially built in 1995, has been continually reinforced physically and augmented with technologies such as infrared cameras. With financing and materials sent by the EU and Spain, Morocco has fortified its border and intensified repression towards Subsaharans in the region.

3.1.2. The northeastern regions: Nador and Oujda

Nador region

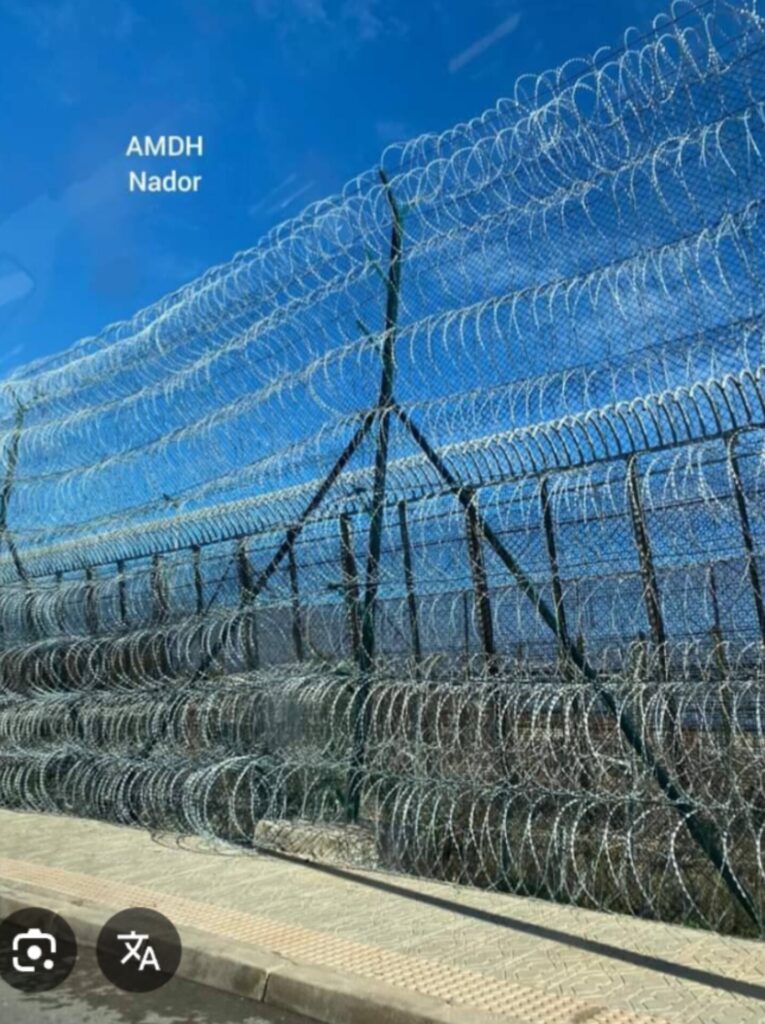

In the context of security strategies at the border zones in the northeast of Morocco, the first picture that comes to mind are the infamous barbed-wired 7m-high fences around the Spanish colony of Melilla. “Fortress Europe” is probably nowhere else so directly visibly evident as in Melilla (and Ceuta).

Border fences enclosing the Spanish colony of Melilla. Source: AMDH NADOR

The seven-meter-tall fences have three parts: one on the Spanish side, one international and one Moroccan. Each is topped with razor-sharp barbed wire, as well as a five-meter pit used as an obstacle and extensive surveillance by authorities. The physical border enclosing Melilla radiates violence and danger, in order to thwart breakthroughs or rather: jumps into the Spanish territory. Hundreds of “Melilla massacres” have taken place, such as the one in which at least 40 people were killed while attempting to cross the border into Melilla on June 24, 2022. AMDH Nador rightfully puts the violent incident into a wider context, stating:

“It became clear to us that the violence was neither circumstantial nor individual, but rather structural and organized. It is part of a public policy based on criminalization […], turning vulnerable populations into objects of security […].”

Millions of euros have been invested in several periods of reinforcements of these barriers, let alone the high maintanence costs. Nevertheless, once in a while groups of people and sometimes individuals manage to overcome all these barriers – of course still suffering from injuries from the fence and violent border guards. The most infamous major attempt to jump the fences ended in the so-called Melilla-massacre mentioned above. But in spite of these massive fortifications, people still try to jump the fences, non-Moroccan nationals as well as Moroccan nationals, lately with women amongst them.

However, security strategies in the zone are much more varied than the physical barriers and border guards’ violence: Violent raids in the makeshift camps of non-Moroccan nationals in the forests around Nador as well as among the harraga communities mostly gathering around Beni Ansar; arbitrary arrests and deportations to the south of Morocco; “no-go” zones at beaches around Nador where the public is banned for better control of sea departures; push-backs (“devoluciones en caliente”) of people that manage to reach Melilla; violence and pushbacks at sea ; criminilization of migration. Quite the package.

Apart from the known, what’s new? For ongoing fortification of the Spanish colony city of Melilla to ‘secure’ it further against illegal immigration, a project of developing a “smart border” between Melilla and Nador has been underway for a year and a half now. It features the implementation of advanced technologies with biometric sensors, high-resolution cameras, automatic license plate recognition systems, and surveillance towers. Artificial intelligence has been a key to the development of this “smart border”, which streamlines and automates a very high percentage of the processes at border crossings. The adaptation of the border post has required an investment of around €11 million, alongside reinvestments in the fenced perimeter of the border of an additional €27 million under the same border fortification ‘wave’. Apart from investing in new technologies, the presence of National Police and Guardia Civil has been increased at the border, with 12 permantly operating control booths at the six lines that exist to enter and exit Melilla.

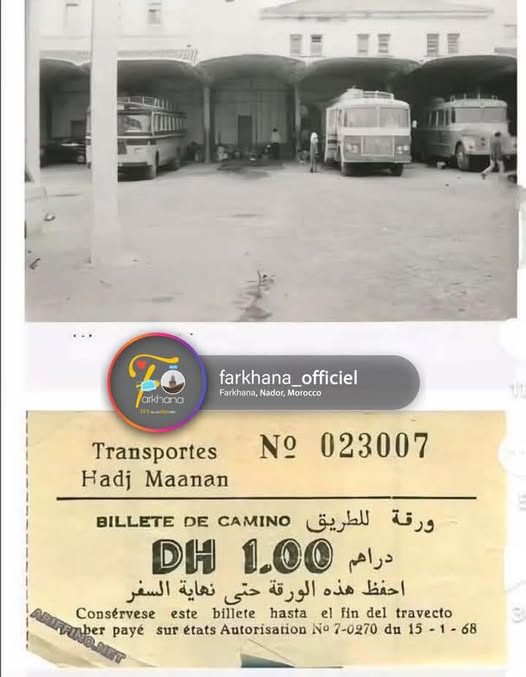

Looking at the frontier today, it is hard to believe that in the early seventies there was a bus line operating from Nador to Melilla for 1 MAD (Moroccon Dirham/currency) only, no barriers, no police checks, very light customs checks, no passports, no visas, no military personnel along the barriers…

Bus line Nador – Farkhana – Melilla. Source: AMDH Nador

Oujda – the frontier of Morocco and Algeria

The Moroccan-Algerian border has been completely closed since 1994. Algeria closed its borders with Morocco in 1994 after Morocco decided to apply visa restrictions to Algerians following a violent attack that killed three Spanish tourists in Marrakesh. Relations with Algeria remain complex until today due to diplomatic tensions, with Algeria backing the Frente Polisario that is resisting the annexation of Western Sahara by Morocco of 1975. But in spite of the complete closure, the border zone between Maghnia and Oujda was and is one of the main points of entry into Moroccan territory for people on the move coming from Algeria.

Algerian-Moroccan border. Source: Alarm Phone

First, in the aftermath of the 1994 closure, smuggling across the border was still thriving (mainly of agricultural goods, petrol, tobacco), and in the 2000s, many people on the move gathered in Magnia on the Algerian side, ultimately crossing to Oujda. There were also heavy crackdowns on camps and large scale deportations in the 2000s, but it was ultimately the 2011 Arab uprisings and the resultant political turmoil that engulfed Libya and Tunisia that drove both Algeria and Morocco to tighten border controls, which obviously also affected communities on the move.

Both governments began reinforcing their architecture for border management, increasing the number of observation posts, regular mobile patrols, and surveillance systems. In the summer of 2013, the Algerian regime started cracking down on smuggled fuel, hoping that regaining lost state revenues would help pay for its investments in border management (among others). In the same year, Morocco started to erect border fences. On the other side, Algeria dug a trench along its border with Morocco, completed in 2016, with a large berm behind it. So the border was gradually reinforced.

Now, the Moroccan-Algerian border around Oujda is protected by metal fences and barbed wire, combined with wide, deep ditches designed to slow down or prevent illegal crossings. The ditches are usually dry, but some sections may contain water in winter, making them more dangerous to cross. The fences, which are 2-4 meters high, are placed before or after the ditch, depending on the area. People coming from Algeria must climb the fence before descending into the ditch. The border is constantly monitored by cameras, radar, and military patrols, involving the National Security Agency, the Royal Gendarmerie, and the Auxiliary Forces. The exact budget for this infrastructure is not public, but according to local activists, in 2022 the National Security Agency had approximately 13 billion MAD (~ 1,2 billion €) at its disposal for its missions, including border surveillance, and Algeria has invested several billion dollars in its border infrastructure.

The strengthening of the border has a direct impact on Oujda: prolonged closure and militarization have reduced cross-border trade, exacerbated precariousness and unemployment, and concentrated migratory flows in the city. The ditches and fences, combined with surveillance and patrols, create a physical and psychological barrier, pushing people on the move towards more dangerous routes and towards resorting to smuggling networks, thus increasing the risk of accidents or death. Pushbacks, border violence and forced deportations are a daily reality that completes the strategy to ‘secure’ the border.

3.1.3. South Morocco

Between 2018 and 2024, more than 100,000 people arrived in the Canary Islands via the Atlantic route. This trend has been declining since early 2025. Increased coastal surveillance by Morocco and, further south, by Mauritania, as well as the violent repression suffered by people travelling through this vast desert, particularly Black people, have caused a shift in migratory movements towards Algeria (see section 3.4 on Spain).

Among the main technological investments, the use of drones is particularly prevalent in the Sahara. Migration control is not the only issue in this region, as evidenced by C., an Alarm Phone colleague who knows the area well:

“I think that when it comes to border control, what stands out most is the use of drones. Drones are used because, for example, in southern Morocco, the areas are quite vast. So sometimes, in terms of operationalising on the ground, guards have a hard time ‘securing’ everything. So they use drones much more to monitor and detect movements, especially in southern Morocco. That’s what comes up most often.

We do know that in the south, for example, security is not only being strengthened because of migration. Do you see what I mean? Security is also being strengthened because of the conflict in the Sahara. So Morocco is trying to mobilise material and military resources both to safeguard its territory and to combat migration. – The two things go hand in hand.”

3.2. Mauritania

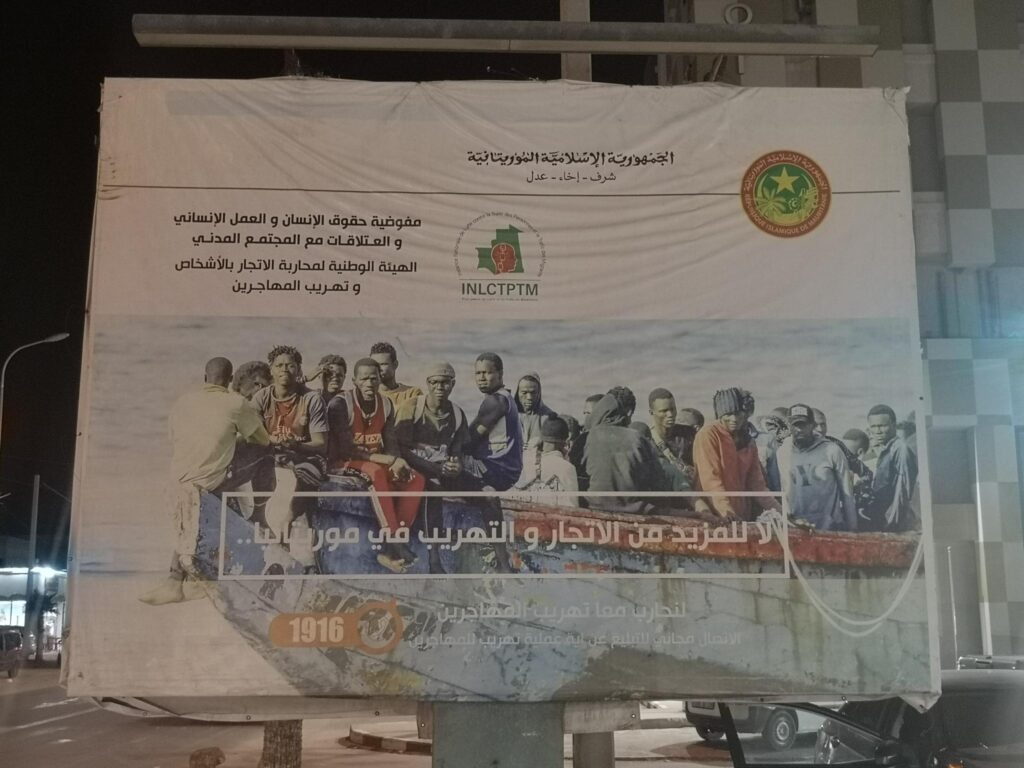

“Islamic Republic of Mauritania: Honour – Fraternity – Justice. Commission on Human Rights, Humanitarian Work and Relations with Civil Society National Authority for Combating Trafficking in Persons and Smuggling of Migrants. ‘No to human trafficking and smuggling of migrants in Mauritania. Together against trafficking.’ Call the toll-free number to report any smuggling operation.” Source: Alarm Phone

In early March 2025, as we were finishing writing the previous report on the theme of imprisonment, the Mauritanian authorities were conducting raids of unprecedented intensity, as reported and documented by civil society and humanitarian organizations such as Human Rights Watch.

In their homes, workplaces, and social spaces, people were subjected to violent and collective arrests. Guided by racist prejudices, Mauritanian police forces forced their way into homes and assaulted people suspected of being illegal immigrants. Among them were “children, pregnant women, asylum seekers, refugees, and people with valid legal status in Mauritania”.

While the intensity of the crackdown came as a surprise, the violence of these operations is nothing new; it has existed at least since the criminalization of migration began under EU interference in 2006.

But these few months of intense arrests and deportations (around 30,000 people between January and April 2025) have been coupled for the first time with systematic biometric registration.

On the ground, a friend tells us:

“According to the testimonies […] of four National Security [police] officers in charge of emigration: upon an arrest, two units are dispatched. One police unit is responsible for interviewing migrants to determine their situation (whether they are undocumented or want to make an illegal trip to Spain). One unit is dispatched by the Ministry of the Interior (registration officer) to record their details (take their photos and scan their fingerprints). Finally, a file is compiled on the migrant and the reasons for their expulsion. Because if the migrant is deported for attempting to travel illegally to Europe or Spain, they are not allowed to return for two years; otherwise they will be deported immediately if they try to return to Mauritania if their fingerprint is detected after a check or an attempt to cross the border. Otherwise, they can return whenever they want, provided they are in good standing.”

The authorities record personal files, such as “biometric fingerprinting, photography […] for the purposes of traceability, protection, and administrative management.”

Testimonies collected by Human Rights Watch between 2018 and 2023 report arbitrary accusations of irregular status, irregular departure, etc. To cloak the deportations linked to these offenses in a veil of legality, the Islamic Republic of Mauritania adopted in November 2024 a set of laws that include the possibility of sentencing those prosecuted for these offenses to imprisonment, fines, and bans on return.

During the registration process and until their expulsion, individuals considered undesirable by the authorities are placed in indefinite detention at the Ksar police station in Nouakchott and in a former school rehabilitated by the EU and nicknamed “Guantanamito” in Nouadhibou. These centers are a veritable torture for those detained (see previous report).

RIM representatives deny that they are carrying out these mass arrests on behalf of European states, preferring to talk about collaboration and sovereignty. According to them, the purpose of these collective expulsions is to ensure national security, “protect migrants against […] smugglers” and dismantle trafficking networks.

This security discourse justifies policies that, in reality, undermine the right to free movement and endanger people on the move. In a joint statement, Mali and Mauritania attempt to combine the security discourse with a positive representation of regional migration as a natural and historical phenomenon that is socially and economically beneficial. However, this requires state involvement to ensure that it is “regular, safe, and orderly”.

Indeed, the right to free movement is considered a fundamental right in West Africa and, moreover, a return to pre-colonial normality. It is guaranteed by regional organisations neighbouring Mauritania: ECOWAS and the AES.

Since leaving ECOWAS in 2000, the RIM has maintained this fundamental freedom through bilateral agreements with Mali and Senegal. However, in recent years, it has become more difficult to reconcile freedom of movement with border security, leading to tensions with Mali and Senegal. This has recently been regulated with Senegal through the signing of new regulations. But relations with Mali remain more uncertain.

These tensions highlight the relative difficulty for the Mauritanian state to balance regional interests and the protection of EU borders.

The actors and the materialisation

The involvement of the EU and its member states is not limited to financing technology, infrastructure, or equipment for the Mauritanian police forces. Through informal bilateral agreements, Frontex, the Guardia Civil, the IOM, etc. ensure a continuous Western human presence to “support” border security.

Since their first interventions in Mauritania in 2006, the Guardia Civil, in collaboration with the EU, and the IOM have participated in the creation and/or modernization of 45 border posts, through material donations and training of various police forces.

Frontex’s presence on the Atlantic route is also long-standing. Between 2006 and 2008, various phases of Operation Hera mobilized European aircraft, helicopters, and ships, in coordination with Morocco, Mauritania, and Senegal, to intercept people on the move. Since then, Frontex’s presence has become more insidious and opaque, and they no longer intervene “directly” in interceptions and pushbacks.

Map 2: Frontex in Africa. Source: This map is from the article Exporting Borders: Frontex and the Expansion of Fortress Europe in West Africa by Mariana Gkliati and Jane Kilpatrick originally published on http://www.tni.org under a Creative Commons licence

It is through the AFIC network, the Africa-Frontex intelligence community, “a network of 31 African states coordinated by Frontex”, that the European agency operates in Mauritania. AFIC trains and provides equipment to the intelligence services of different countries to centralize real-time information on migratory movements in the region through a simultaneous database. To this end, it trains Risk Analysis Cells (RACs) in Mauritania, which have been in place since 2022 and are run by the National Gendarmerie and the Air and Border Police Directorate (DPAF).

Through AFIC, Frontex plays a major role in implementing the European model of biometric files in the region. The aim of this widespread filing is also to facilitate the identification of individuals and their return to their countries of origin.

Since 2011, Frontex has had the power to coordinate directly with third countries through informal agreements that do not require a vote in the European Parliament. However, without formal agreements, Frontex cannot envisage an operational presence in its own name. Since July 2022, negotiations have been underway on a formal agreement between the Mauritanian state and the agency (status agreement and/or working agreement), without opposition from the European Parliament, which has introduced recommendations for vigilance on human rights. To date, the negotiations have not been successful, and the Mauritanian state, under pressure from civil society, is moving cautiously to maintain the illusion of its total sovereignty over the security of its borders. In the absence of a direct agreement with Frontex, it was the EU itself that signed agreements in early 2024 and released €210 million (see previous report).

The precise use of this funding is difficult to trace, but following the visit of the President of the European Commission in February 2024, the Mauritanian army received new equipment, including drones. The army plays a central role in monitoring the kilometers of coastline to the east and the vast desert expanses to the west. In the desert border region with Mali, units of drone pilots on camels have been financed thanks to EU funding.

The provision of biometric control equipment, whether under the AFIC or agreements with the EU, is the most recent manifestation of the outsourcing of the EU’s borders to Mauritania. Biometric tools are central to the readmission strategy reaffirmed by the EU in the European Pact on Migration and Asylum (EPMA).

The EU’s borders are therefore increasingly materializing in the south. The AFIC network, linked to Interpol, is working to increase control in a territorial space that is nevertheless regulated by free movement agreements, as a member of Alarm Phone Sahara explains:

“African borders have been monitored and controlled for decades. Unlike countries where there is a lot of advanced technology, in Africa it is much more about the militarization of borders. And these borders start from the first city, let me explain. If, for example, I leave Cameroon, at the first border post in Cameroon, if I want to enter Nigeria, for example, the Cameroonian police themselves start asking me questions. Where are you going? Why? […] And if I manage to get through the first checkpoint in Nigeria, it continues.

But the tightening of controls, this so-called ‘security’ dynamic, supported by international partners, exposes people on the move to even more violations of their fundamental rights.

For economic reasons (informal trade, etc.), social reasons (transhumance, etc.) and/or for their own safety (refugees), migratory movements persist and are caught between the violence of states and that of armed groups and/or organized networks.”

Foreigners still present on Mauritanian territory live in a climate of intimidation and constant fear of controls and state violence, which leads to social isolation.

After being turned back under abusive deportation and expulsion conditions (physical violence, racketeering, lack of water, food, etc.), many remain stranded in transit zones in extremely alarming conditions, deprived of drinking water, food, or shelter and forced into serious forms of exploitation, particularly sexual exploitation, as evidenced by this touching poem by a friend who visited Rosso last April:

“The silent cry of migrant women… Between dream and abandonment

In the forgotten corners of the borders, women walk forward, carrying burdens heavier than their bags on their shoulders. They have left everything behind: their homes, their land, their dreams… And instead of finding safety, they have found unfamiliar faces, nights of fear, and relentless cruelty.

A mother hugs her three children close, no longer knowing whether her pain comes from the hunger gnawing at their bodies or the fear that haunts them every night. A young girl barely sixteen years old stares at the horizon with empty eyes, as if life had left her too soon.

No hospital to treat their wounds, no shelter from the rain, no bread to satisfy their hunger. And worse still: violence… the violence of bandits, the violence of need, the violence of silence.

These women are not seeking pity, but a chance… a helping hand, a listening ear, a compassionate heart.

But where are the humanitarian organizations? Where are the government authorities? Where are those who have the power to act? Isn’t it time for human conscience to respond to the call of those who are not heard?

I suffer for what they are going through, and I wonder: how can we help them? How can we lighten such a burden? I don’t have all the answers… but I believe that sincere attention, the right words, and humane actions can change destiny.”

Smugglers take advantage of this situation to charge more for their services and their knowledge of the terrain. And at border posts, security forces do not hesitate to extort money from foreigners. This ambiguous coexistence, which resembles collusion, inevitably leads to economic violence.

Regardless of organized networks, the externalization of borders shifts migration routes to more dangerous areas (desert, sea). This leads to more accidents, shipwrecks, and deaths.

This testimony echoes that of the Alarm Phone Sahara member quoted above, who adds:

“When conditions were very harsh on the Niger side, migrants tended to use the Mauritania and Mali routes to enter Algeria directly. […] But now that Mauritania has also started to turn people back in large numbers, don’t be surprised if people start using the Bamako route again. […] Mali will see the same number of migrants entering as before. […] Except that this time it will be a little complicated to get to Gao because the road is really mined, there are anti-personnel mines, bus attacks en route, looting. This is the information we give to migrants when they arrive. If you want to go through Gao, it’s at your own risk because that’s what’s happening on the road right now.”

As we finalize this report, we are deeply saddened by the death and disappearance of more than 140 people who were shipwrecked off the coast of Mauritania while traveling from the Gambia (located more than 1,600 km from the Canary Islands).

Our thoughts go out to all the victims of these deadly policies that make the world more xenophobic every day. We wish to oppose them with all our solidarity and send courage and love to all those, and others, who are victims of the commercialism and coldness of those who govern us.

3.3. Senegal

In Senegal, securing migration has been a political priority for several years, often driven by EU funding. It is accompanied by surveillance technologies and cooperation agreements that transform mobility management into a military and police matter. This dynamic is part of a broader trend of border externalization led by the EU, but also of national policies that reinforce the criminalization of departures. This situation pushes migrants to take much more dangerous routes to embarkation points.

EU funding is not limited to abstract programs: It translates into the concrete delivery of surveillance equipment and the deployment of control units on the ground. In October 2023, Spain delivered six multicopter drones to the Senegalese police, intended to detect boat departures as part of joint patrols. At the same time, Spain deployed a CN-235 patrol aircraft, as well as 38 Guardia Civil officers, supported by four patrol boats, a helicopter, and thirteen all-terrain vehicles, to reinforce maritime and coastal surveillance alongside Senegalese forces.

Patrols by the Guardia Civil at Fass Boye. Source: Alarm Phone

In February 2025, the European Union delivered two STRIX 425 tactical drone systems to the Senegalese gendarmerie as part of the Joint Operational Partnership (POC II). These long-endurance aircraft, designed for aerial and maritime surveillance over large areas, represent a significant upgrade to Senegal’s surveillance arsenal. This partnership “reflects the common desire of both parties to strengthen regional security through a proactive and technological approach”. Beyond drones, the EU has strengthened land-based capabilities. In 2020, it delivered 26 vehicles to the Air and Border Police Directorate (DPAF) as part of the “SENSEC-EU” program (a cooperation program for internal security between Senegal and the EU). In 2025, the European Union provided even more state-of-the-art technical equipment to the Senegalese national police as part of a program to strengthen border control capabilities, including equipment for detecting document fraud (video analyzers and computers).

Frontex, the EU’s best-equipped agency, is creating the conditions for this border security in Senegal, but remains little known to the country’s inhabitants. In 2019, Frontex opened a risk analysis unit in Dakar, set up in partnership with the Senegalese authorities, whose mission is to analyze and process migration data in order to anticipate flows and guide security responses. It has supported the installation of biometric border posts since 2018. The EU is considering signing agreements that would allow Frontex agents to act with executive powers, including judicial immunity on Senegalese territory. This framework illustrates Frontex’s shift from providing simple technical support to becoming an institutionalized actor in Senegal, with prerogatives similar to those of a direct intervention service. These security projects are facing growing opposition from migrant rights activists because they threaten sovereignty and human rights, and are the target of the annual “Push Back Frontex” campaign by Boza Fii, a Senegalese migrant rights association. Since the advent of Frontex and the numerous agreements put in place to secure “migration”, many people have been struggling, feeling like prisoners in their own homes. The discourse of the authorities and their collaborators (the European Union) is one of safe and regular migration. But in reality, the mechanism that has been put in place is nothing more than selective and sometimes even resembles a scam or fraud, which is particularly evident in visa application procedures.

Today, in the city of Mbour, for example, this situation has left many scars on several families who have lost several members of their families on this long and perilous journey. And to this day, some families still refuse to mourn their loved ones, as they continue to hope that one day their children will return.

In addition to bilateral agreements, Senegal has taken the initiative to strengthen its own border security structures. The Senegalese Armed Forces are working together to combat emigration. The Navy and Air Force are collaborating to monitor the coastline and intercept boats. The Interministerial Committee for the Fight against Irregular Migration (CILMI), created by decree in March 2024 to coordinate the national policy on mobility control, illustrates the country’s shift towards security. According to its permanent secretary, security forces intercepted 5,192 migrants in 2024, 407 of whom were prosecuted. The CILMI relies on a territorial network of regional and departmental committees and promotes a participatory approach, even setting up a toll-free number encouraging citizens to report departures. In July 2025, a single operation intercepted 201 migrants in the Saloum Delta. But this strategy, reinforced by the president’s rhetoric of a “relentless hunt” for smugglers, tends to shift routes to more dangerous areas, contributing to a dramatic increase in deaths on the Atlantic route.

The securitisation of migration in Senegal illustrates the failure of European and national policies: massive funding, intrusive technologies, and the criminalisation of mobility, but with tragic results. By making migration routes more dangerous and breaking down local solidarity, these measures take a heavy human toll. Creating safe routes is essential to preserving human dignity and freedom of movement.

3.4. Spain

In July 2025, interceptions of arrivals by sea to Spanish territory went down by almost 29% compared to the same period the previous years. (The figures cited here come from the Spanish Ministry of the Interior, which is why we use the term ‘interceptions’ rather than ‘rescues’.) Interceptions in the Strait of Gibraltar, Ceuta and Melilla, and the western part of the Alboran Sea continued their downward trend, likely due to increased surveillance in the area and greater cooperation with the Moroccan government. The Atlantic route has also seen a decrease of almost 42% compared to the same period in the previous year, also because of the externalization of border controls to countries of origin and transit in the region, mainly Mauritania, Senegal, Morocco and Mali. By contrast, arrivals to the Balearic Islands have gone up. Algeria (the country most people on the move taking this route leave from) does not cooperate with Spain and the EU.

These developments highlight, on the one hand, the continuity of the reasons why people cross the sea and the nearly total absence of safe and legal migration channels.

On the other hand, decision makers continue to push for the further sealing of the border at sea through a three-pronged strategy of advanced technology (particularly aerospace technology), militarization, and externalization. These strategies have been in place since 2005 (first Frontex HERA Operation), deepened after 2018 (when the politicization of migration by sea and, in particular, rescues, accelerated), and have been supercharged with the development of new technical surveillance capabilities.

In terms of the main actors present in the Spanish zone of responsibility, one thing that sets Spain apart from other sections of the EU’s external maritime border is the relatively more discrete presence of Frontex; the agency is present but often limits itself to the role of observer and data collector once people on the move arrive at port after a rescue. Another difference is that Salvamento Marítimo continues to respond to distress calls where migrant boats are involved. Salvamento Marítimo is the non-militarized government agency responsible for addressing emergencies at sea in the Spanish zone of responsibility, which carries out most of the rescue operations. However, the agency’s independence is increasingly compromised: since 2006/2008 in the Canary Islands, and since 2018 in the Western Mediterranean region the Guardia Civil (a militarized security force within the Ministry of the Interior) takes over operational responsibility of most, if not all, rescues where the lives at risk are those of people on the move. Meanwhile, operational decisions for all other rescues involving tourists, fisherfolk, merchant vessels, etc. remain within the hands of the civil agency, with no military involvement with very few exceptions. The National Police is only present at port, and mainly involved in the detention, transfer, and prosecution of people on the move once they have arrived in the territory.

Outside of the national territory, Spain collaborates mainly with militarized security forces in so-called countries of origin and transit: Key partners are the Ministries of the Interior, Navies, and Police Forces in Morocco, Mauritania, Senegal, Gambia, and Mali. These receive in-cash funding from the EU and Spain, but also equipment, training, and preferential treatment in other areas such as commerce and temporary migration schemes. In the Canary Islands in particular, the deepening of the collaboration with the Mauritanian government since 2023 and the ensuing repression of mobility by sea are directly related to the sharp decrease in arrivals. Other factors also account for this reduction, for example, the stabilization of the political situation in Senegal, which was a key reason for the departure of thousands of youth in 2023.

Along with externalization and the transfer of surveillance and interception responsibilities to collaborating African governments, a relatively recent development is the application of surveillance technology in the Spanish zone of responsibility. Land-based and airborne radars have been used for a few years now to increase surveillance in these areas (the SIVE system, managed by the Guardia Civil), but these technologies have proven vastly insufficient, particularly in the enormous Atlantic region.

SIVE radar (non-operational) located north of Lanzarote, Canary Islands, Spain. Source: Alarm Phone

A new EU-funded pilot project called Agamenon in the Canary Islands seeks to test the possibility of providing around-the-clock surveillance in this area with a mix of pseudo-satellites, drones, and software trained to detect, identify, and communicate the presence of migrant boats to European State Security Forces. The Ministry of the Interior of Gambia and the National Police of Senegal are associate partners of the project. The Agamenon project is presented as a pioneering initiative that could save many lives and effectively combat mafias. The hypocrisy of states seems to know no bounds, but from our experience on the ground, we know that the more border surveillance increases, the longer the list of those who die or disappear at sea becomes. The following section is heartbreaking proof of this.

4. Shipwrecks and missing people

As our comrades at Alarm Phone write in episode 33 of the Chroniques àMER podcast,

“when we hear ‘I lost my brother’ or ‘I lost my son…’, the pain is not only that of loss, but also that of uncertainty, of not having a grave to mourn at, no truth to cling to. This pain is never the same depending on the relationship with death, with mourning, depending on the secrets contained in each language. That is why each disappearance is unique. And the words of those who live are always precious, intimate, and political.”

There, you can listen to Ndeye’s powerful testimony:

“My name is Ndeye. I am a Senegalese national and I lost my little brother on April 29, 2024. […] You never get over it. It’s true, my brother is dead, but that doesn’t mean he’s dead to me. He is more alive than perhaps many people I know. He lives in my heart. I often talk to him, I have his belongings, I have his photos, and I see him in my dreams. […] Yesterday, when we were at the beach, I broke down. I cried my eyes out. It hasn’t been long since I mourned him, but yesterday it was as if it was obvious that he was no longer there. It was like a kind of proof. Because I tell myself, if he were here, why did I come here? Because it’s a commemoration. A commemoration for whom? For the dead and the missing. So if I had my brother with me, I certainly wouldn’t be here. Before I accepted that he was dead, I told myself that he was somewhere in Morocco, somewhere in Tunisia. When I got confirmation from someone who was on the boat who contacted me and told me you have to resign yourself, he’s really gone, I’m a witness, I saw him leave. All of that tore me apart, it broke me, I was devastated and it was really horrible. […] You live with it and it’s a trauma that haunts you, like a weight here inside your heart. And I still have that. […] And every time someone loses a family member, a loved one or a friend in the same circumstances as we did, we relive the same thing. It’s as if they’ve just died. It’s as if you’ve just lost them again. It’s very difficult because it’s something we experience every day, so each time it’s as if they’ve just died today.”

On 1 March, a young man, possibly a minor, drowns and two people, including a 26 year-old Algerian man, are declared missing after a group of twelve young people swam from Morocco towards Ceuta during the previous night.

On 3 March, on Al-Fnideq beach, Morocco, a minor who had been missing for four days is found. He had drowned while swimming towards Ceuta along with other young people. The Ceuta authorities had announced three days before that a number of people on the move had drowned among a group that tried to reach the city by swimming.

On 4 March, a young man wearing sports clothing and a life jacket is found dead on the Son Moll beach in Capdepera, Mallorca.

On 5 March, a 33-year-old man from Tetouan is missing since the previous Friday night. He had taken the sea from Morocco to Ceuta, attempting to cross the border during a night of bad weather and lower Moroccan surveillance.

On the same day, witnesses find a dead person wearing a wetsuit in front of the La Caracola beach bar, in Fuengirola, Málaga, Spain. The person’s body has been washed up by the storm.

On the same day, a 39-year-old man on the move is identified after being fatally hit by a car on a road near Vera, Almería, Spain.

On 6 March on a beach in Formentera, Balearic Islands, Spain, the sea washes up someone’s body. It is deemed very likely that the person was on the move and disappeared during the journey by boat from the coast of Algeria to the Balearic Islands.

On 7 March, a drifting rubber boat is spotted by fishermen south of Cape Verde with nine dead people on board. The boat’s initial plan could have been to travel from Senegal towards the Canary Islands, Spain.

On 8 March, at Cala Deià, la Serra de Tramuntana, Mallorca, Spain, someone’s body is found washed up by the sea. The person who died is allegedly aged between 17 and 20 and wore a life jacket.

On 12 March, a wooden fisherboat from Mauritania is rescued adrift after 20 days at sea. The thirteen survivors disembark in Dakhla, Morocco, and attest that at least 72 travel companions died during the journey.

On 13 March, neighbours around Benzú, in Ceuta, see a young man in the sea until he is swallowed by the waves. The weather is very stormy, and he was trying to cross the border towards Ceuta. The witnesses deem it impossible that he could reach the shore, and he has been missing since.

On 14 March, a dead woman is found near the Port of Can Pastilla, Palma, Mallorca, Balearic Islands, Spain. The Guardia Civil estimates that she could have died during the shipwreck of her boat, during a trip from Algeria to the Balearic Islands.

On 17 March, on the beach of s’Arenal, Mallorca, Balearic Islands, Spain, a dead person is found. Local media state that everything points to them being someone on the move who was travelling in a small boat.

On the same day, another dead person is found in Cala Mesquida, in the Capdepera area of Mallorca, Balearic Islands, Spain. Someone was walking along the beach, found them and noticed that they were wearing an orange life jacket. Local media also deemed it most likely that the person was on the move and shipwrecked during a crossing in a small boat from North Africa.

On 18 March, a boat with 28 people aboard leaves Algeria towards the Balearic Islands, Spain. They have been missing since, and their relatives have heard that the boat shipwrecked.

On 19 March, a dead person is found ashore near the beach Juan XXIII, in Ceuta. Initial hypotheses suggest that they were a young person on the move who had attempted to swim across from Morocco and drowned.

On 23 March, a dead person is found floating around 12 nautical miles off Ceuta, in the Strait of Gibraltar. The vessel that discovered him confirms that he was a young man, North African, and wearing a wetsuit. This leads to the assumption that he had attempted to swim to Ceuta and had been swept out to sea by strong currents.

On the same day, two young Algerian people are reported missing, two weeks after their attempt to reach Ceuta by swimming from the coast of Al Hoceima, Morocco.

On 24 March, in Carboneras, near Almería, Spain, a man in his 30s falls into the sea and dies while his boat is reaching Los Muertos beach.

On 26 March, someone on the move, aged around 25, drowns after being thrown into the sea while approaching the shore at Cala de Enmedio, near Almería, Spain.

On 29 March, 40 people who departed two weeks ago from Mbour, Senegal, are still missing despite a plane search carried out by Salvamento Marítimo.

On 30 March, a small boat carrying 36 people arrives at Cala Mochuela, near Almería, Spain. Two passengers of this boat are taken to the local hospital, and one of them dies.

On 13 April, in the Ait Oufla district (Middlet, Morocco), two migrants were swept away by flash floods due to heavy rainfall. Local residents managed to rescue one of them in time, but the other person died during the flood and was found later several kilometres away. They were on their way to the north in an attempt to reach the city of Ceuta.

On the same day, the body of a dead person was found in the maritime zone of Escorca (Balearic Islands, Spain) and moved to the port of Sóller. The person probably drowned while on their way to the Balearic islands by boat.

On 15 April, the body of a dead person was found floating in the canal between Ibiza and Formentera (Balearic Islands, Spain). The person also probably drowned while on their way to these islands by boat.

On 30 April, a young man drowns while swimming from the coast of Al Hoceima, Morrocco to the city of Ceuta.

On the same day, a dead woman’s body is found on Azla Beach in the city of Tetouan, Morocco, after being washed up by the waves.

On the same day, a dead man’s body is found on Cala Tortuga in the north of Menorca, Balearic Islands, Spain. One of the investigations’ hypotheses is that he may have died while travelling by boat between Algeria and the Balearic Islands.

On 4 May, two small boats adrift at sea are rescued in Ibiza, Balearic Islands, Spain. Two people had died, and a pregnant woman had lost her baby during the trip.

On 8 May, a small boat is rescued 62 nautical miles off the coast of Alicante, Spain. Among the 16 passengers, one person died during the trip. The boat departed from Algeria and has been adrift for several days.

On 26 May, a group of 21 people depart from Algiers heading towards Spain. They have been missing since then.

On 28 May, four women and three girls die in the capsizing of their 150-passengers boat, as the boat was approaching the port of La Restinga, El Hierro, Canary Islands, Spain.

On 29 May, 22 people depart from Bourmedes in Algeria, heading towards Spain. They have been missing since then.

On 30 May, a dead person is found on Migjorn beach, on the coast of the island of Formentera, Balearic Islands, Spain. Authorities declare that they will try to identify the body and determine whether it corresponds to any of the people on the move who disappeared while trying to reach the Pitiusas.

On 31 May, someone is found dead on a beach in Níjar, Almería, Spain, after arriving in a small boat with three other companions.

On the same day, two dead people are found drowned in the sea off the coast of Formentera in the Balearic Islands.

On the same day, 25 people depart from Bourmedes in Algeria heading to Spain. They have been missing since then, possibly as a result of another invisible shipwreck, as for the two other boats on the previous days. (source: Alarm Phone)

On 1 June, a dead person is found in the area of the Espardell Island, Formentera in the Balearic Islands, probably after having departed from Algeria.

On 2 June, a dead person is found on Sant Francesc beach, Formentera in the Balearic Islands, probably after having departed from Algeria.

On 3 June, a dead person is found ashore at Llevant beach, Formentera in the Balearic Islands, probably after having departed from Algeria.

On the same day, a dead person is found in the Balearic Sea, off the coast of Santa Eulària in the Balearic Islands.

On 4 June, four of 38 people lose their lives when a rubber boat on its way to the Canary Islands capsizes off the northern coast of the province of Laâyoune-Sakia El Hamra between Laâyoune and Tarfaya. Authorities rescue the remaining passengers, and the bodies of the deceased are transported to the morgue at Moulay Hassan Ben Mehdi Regional Hospital in Laâyoune. The Royal Gendarmerie launches an investigation, thereby contributing to criminalizing people on the move.

On 5 June, a dead person is found floating near Punta Prima, Formentera in the Balearic Islands. It has been the eighth body found whitin a week in the Balearic Islands.

On 6 June, the Moroccan authorities find a boat that shipwrecked with 52 people off the coast in the area of Tarfaya. Among them, eight bodies are recovered, and several other people are hospitalized.

On 7 June, one person wearing a neoprene suit and flippers is found dead by the Guardia Civial off the coast of the Santa Catalina area in Ceuta.

On 18 June, Salvamento Marítimo rescues a boat carrying 20 young people, including four minors, in the sea off the coast of Alicante. The boat has been adrift for 14 days, and the travellers are found in an extremely weak state of health. Two of them are hospitalized. Passengers tell the media teams that five people lost their lives during the journey.

On 20 June, a boat is found on a beach in northern Mauritania. The boat had departed from Kamsar in Guinea 11 days before. 96 people survived and report at least 3 deaths at sea. Four people are taken to hospital, and the rest of the group is detained by the gendarmerie in Mauritania before being deported back south.

On 1 July, a Moroccan fishing boat named “Kheir Eddine” rescues 50 people in critical health condition off the coast of Al-Watiya in the province of Tan-Tan after the travellers’ boat broke down four days earlier. One person dies, and seven more are still missing. The military police has opened an investigation, thereby contributing to criminalizing people on the move.

On 17 July, one person is found drowned wearing a neophrene suit by the Guardia Civil about 50 meters from the beach in the Sarchal area in Ceuta.

On 29 July, one young person is found dead by the Guardia Civil close to the shore in the southern bay in the area opposite the Juan XXIII neighborhood in Ceuta. Judging by the condition of the body, the person has been dead for some time.

On 30 July, Oussama Hamham, a 22 year-old Morrocan footballer player, is shot dead by the Algerian navy near Saidia. The speedboat on which he was traveling drifted into Algerian territorial waters while trying to avoid Moroccan patrols. At that point, an Algerian navy unit reportedly intervened and opened fire on the boat. He died at sea before the rest of the group reached the Spanish coast.

On 4 August, Salvamento Marítimo rescues a group of 176 travellers, among whom one person is found dead, 476 kilometers southwest of Gran Canaria in the Canary Islands. The rescue operation takes place after the French Navy warship Beautemps-Beaupré was alerted to the boat. Five people, including a pregnant women, are hospitalized.

On 10 August, one person is found dead caught in a fishing net by fishermen off the coast of Al-Madiq in Morroco. The young man probably drowned trying to reach Ceuta by swimming.

On 14 August, one young man is found drowned by the Guardia Civil off the coasts of Fuente Caballo in Ceuta.

On 20 August, a boat shipwrecks off Mallorca after people have spent seven days at sea between Algeria and Spain. One person is found dead and three remain missing. 19 people survive and are brought to Mallorca.

On the same day, one person is found drowned wearing a wetsuit and fins off Desnarigado beach near Mount Hacho in Ceuta, Spain.

On 22 August, 14 people are rescued to Mallorca in the Balearic Islands, while 12 more people are still missing after jumping into the water when their boat capsized.

On the same day, 26 people on another boat go missing.

On 27 August, one young person, probably a minor, is found drowned near Ceuta.

On the same day, a boat carrying more than 140 people that departed from the Gambia capsizes off the coast of Mauritania, near Mhaijratt. Only 16 people manage to reach the shore and survive.

CommemorAction at the Transborder Summer Camp. Source: Alarm Phone

All these are not isolated “tragedies” or random “accidents”—they are the predictable outcome of the EU’s deliberate border policies. Each death and each shipwreck is the direct result of a system that treats human mobility as a threat to be contained instead of as a fundemental right. Our sorrow for the lives lost is inseparable from our anger: This is not border “management”. It is border killings. It is structural violence, executed by European states and their allies. And it is entirely preventable.