Last year was the deadliest ever at the United Kingdom’s (UK) external border. Calais Migrant Solidarity recorded at least 89 confirmed deaths at the border, of which 69 were reported by the Refugee Council to be people who died or went missing during attempts to cross the Channel in ‘small boats’. The French and British governments have been quick to blame people smugglers, but Alarm Phone showed already at the beginning of the year how state initiatives to ‘stop the boats’ were driving overcrowding and causing deadly incidents.

Here we zoom in on one event which demonstrates how authorities can neglect migrants at sea, then punish survivors when deaths occur. For this report we spoke with survivors arrested after they were rescued and returned to France, and examine official coastguard documents obtained through freedom of information requests.

Twice abandoned – MIGRANT 11, 28 February, 2024

French Navy rescue diver communicates with people onboard dinghy. Image from Préfecture Maritime de la Manche et de la Mer du Nord press release from 28 February, 2024.

Key events timeline:

- At 09:20 UTC an overcrowded dinghy (French designation MIGRANT 11 / HM Coastguard General Incident Number 505659) with 60 people onboard was left unattended by the French coastguard during its journey across the Channel.

- Around 10:00, four people fall overboard due to the high seas.

- At 10:15 a French Gendarmerie vessel VSMP EULIMÈNE reached the dinghy. The people tried to get the attention of the crew to report that people had fallen in the water, but were ignored.

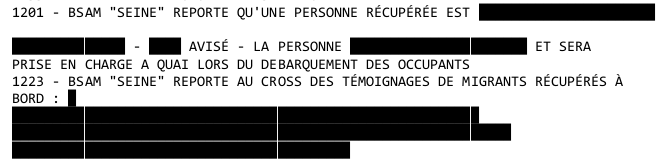

- At 10:32 EULIMÈNE reports the dinghy stopped moving. Shortly after, the French Navy ship BSAM SEINE arrives on scene and begins to rescue the remaining 56 people from the drifting dinghy.

- The rescue finishes just before 12:00. At 12:23 the SEINE reports survivors say four people had fallen into the sea. The French Maritime Rescue Coordination Centre (MRCC) at Gris-Nez waits around 20 minutes before beginning the search.

- At 14:00 a French helicopter spots three people in the water. Only one is recovered (unconscious) by the SEINE and later declared deceased on the quay.

- The French MRCC does not inform HM Coastguard Dover of the situation until 14:09, delaying the full search for people in the water by more than one and half hours.

- Despite having seen three people in the water and only recovering one, the French abandon their search at 15:06, after just one hour.

- The UK Coastguard continues searching with planes, helicopters and lifeboats until 01:00, 29 February after calculating the upper realistic limit of survivability for people in the water to be 13-14 hours.

- Three people remain lost at sea.

- The French police arrest three survivors from Eritrea. One is charged with manslaughter and today remains in prison awaiting trial. He maintains his innocence.

One survivor, who we will call Omar, told Alarm Phone that he was taken by car with a large group of people from Dunkirk camp to a beach where they slept on the night of 27 February 2024. At around 07:00 UTC the next morning they departed in an inflatable dinghy towards the UK. The French coastguard was first alerted to the overloaded dinghy at 07:27 in position 50° 53.05’ N, 001° 37.88’ E, just off the coast of Wissant. At 08:02 the French rescue ship ABEILLE NORMANDIE was sent to find the dinghy, and at 08:23 reported to have found it and counted 60 people onboard. The ABEILLE NORMANDIE began to follow MIGRANT 11 as it continued towards the UK to be on hand to act swiftly in case of catastrophe. However, at 09:20, after just one hour, the rescue ship was redirected by the MRCC Gris-Nez to another incident further south which had gotten into difficulty and become a priority. The EULIMÈNE, a small fast boat from the Gendarmerie Nationale, was sent to MIGRANT 11 to replace the ABEILLE NORMANDIE. This left the people on MIGRANT 11 alone for an extended period without a safety vessel close by to protect them.

According to Omar, as they got further into the Channel the waves became bigger. The dinghy was made only of inflatable tubes and a plastic floor which flexed up and down with the waves; there was no rigid hull. As seen in the photo above, people are riding on top of these tubes with nothing to hold on to. Following the impact of one wave, some people fell overboard into the sea. There was a lot of confusion onboard, and many did not understand what happened as they were from different countries and spoke different languages. Omar, and most others, could not see past the bodies of the others surrounding them in the overcrowded dinghy. This was around 10:00.

Soon after, around 10:15, the EULIMÈNE arrives on-scene, but keeps its distance. Omar explained how people onboard the dinghy shouted and waved to get the EULIMÈNE’s attention, but were ignored. The French coastguard logs show that at 10:32 the EULIMÈNE reports the dinghy is dead in the water, and around 15 minutes later the SEINE, a large Navy ship, launches its fast boats to begin the rescue of the remaining people onboard MIGRANT 11. It takes around 30 minutes to rescue the 56 remaining people.

Once the survivors are safely onboard the SEINE they are finally able to communicate with the French crew and explain people are missing in the water. The French coastguard’s logs have been redacted, so we cannot know exactly what they were told. After this testimony, however, Gris-Nez first spends 20 minutes trying to confirm with the ABEILLE NORMANDIE and the EULIMÈNE that no one had gone overboard before finally beginning to organise a search at 12:45, more than two and half hours after the people had fallen into the sea. At 12:50 the SEINE spots a possible person in the water on its starboard side.

Having just found three people, it could be expected that Gris-Nez would continue searching until the other two are recovered, or it is determined they could not possibly still be alive. However, the French coastguard calls off its search after only hour, at 15:06, abandoning the people a second time. Meanwhile, HM Coastguard continues searching with its fixed-wing aircraft and then tasks two RNLI Lifeboats from Ramsgate and Dover to join at 15:20. The partially redacted conversation between a British and French coastguard officer later that night reveals how the French acknowledged they started their search two hours late and then quickly terminated it for reasons which are not clear. HM Coastguard continued searching for the next nine hours, determining that survivability in the 9° water was between 13 and 14 hours and ‘giving the casualty the benefit of the doubt’.

Who’s to blame?

Many questions remain regarding the 28 February incident:

- Could lives have been saved if the people of MIGRANT 11 were listened to when they tried raising the alarm as the EULIMÈNE arrived at 10:15 UTC, or if a full multi-national SAR operation was immediately launched after the situation became clearer onboard the SEINE?

- How many people are still missing? The ABEILLE NORMANDIE counted 60 persons onboard the dinghy (only 56 were eventually rescued), and survivors first reported four fell into the water. The coastguards only thought they were searching for three people because that was how many the French helicopter spotted four hours later, but was another person left at sea in addition to the two officially missing?

- Why did the French stop the search operations after recovering only one of the bodies, leaving the other two to drift away again? The Maritime Prefecture’s press release cites ‘worsening weather conditions in the area [were] making investigations difficult’ but the British searched for a further ten hours, well into the night.

- Who are those who lost their lives that day? We know the deceased person recovered by the SEINE was Eren Gûndogu, a man from Turkish Kurdistan aged 22, but who are the missing? The Red Cross received many reports of people searching for Iraqi Kurdish nationals after that day, but without recovering the human remains it will likely never be known who and how many perished. In the absence of diligent investigative work to find and determine the identities of those who go missing in the Channel, the true death toll of the UK border goes unacknowledged.

Despite the visible negligence of the French authorities one year ago, they have attempted to shift focus from their actions by blaming the survivors. Omar told us that after SEINE returned to Calais port three survivors were arrested and taken to the police station. There they were interrogated, shown photographs of passengers and asked to identify the driver. After three days, two of them were taken to the detention centre in Coquelles and the third, who we will call Mahmoud, was taken to Longuenesse prison and charged with involuntary homicide as well as for assistance in illegal entry and stay, with the aggravating circumstances of being part of an organised gang and exposing others to an immediate risk of death. He risks up to 15 years imprisonment if convicted. Today, one year later, he is still in pre-trial detention and maintains his innocence.

The arrest and prosecution of Mahmoud is part of a greater trend of arresting, prosecuting and re-traumatising survivors of tragedies in the Channel. Perhaps the most famous case is that of Ibrahima Bâ, a young Senegalese man, scapegoated and sentenced to nine and a half years in detention in the UK following a shipwreck in December 2022. And while Bâ is the only person to have been charged in the UK for manslaughter—the Home Office predominately arrest and imprison the boat drivers of successful journeys—France has arrested, charged and imprisoned at least 10 people who are alleged to have driven dinghies from which people died in French waters. Some may have agreed to pilot the boat as they did not have enough money to pay the smuggler for their journeys, while others claim they were not the driver and have been misidentified through racist profiling by the French police who believe boat drivers are more likely to be Black.

The fact of whether they drove the boat or not does not make them responsible for any deaths which may have occurred. Unfortunately, the risks of Channel crossings today are well known to all who agree to undertake the journey, and are only being made worse through the increased border policing which drives overcrowding and increases the dangers.

Wilful ignorance of the consequences of state efforts to ‘stop the boats’, disbelieving people and abandoning searches early, then blaming survivors for the deaths which occur are all convenient ways for the French and UK governments to deflect responsibility for the human catastrophe they have been inflicting at the border over the last year. But for every life taken from us by the border, the prison or the sea we will not forget and not forgive. We demand an end to border policing in the Channel, an end to the criminalisation of migration, and free movement for all.

Wilful ignorance of the consequences of state efforts to ‘stop the boats’, disbelieving people and abandoning searches early, then blaming survivors for the deaths which occur are all convenient ways for the French and UK governments to deflect responsibility for the human catastrophe they have been inflicting at the border over the last year. But for every life taken from us by the border, the prison or the sea we will not forget and not forgive. We demand an end to border policing in the Channel, an end to the criminalisation of migration, and free movement for all.