Last week clearly showed how Channel crossings have become more dangerous during the past year. Six people lost their lives in three different incidents (the most we’ve seen in a seven-day period), and survivors told associations in Calais still others may be missing at sea. Joint British and French efforts to ‘stop the boats’ played a major role in the severe overcrowding of the dinghies involved in these incidents. Each time rescuers were close at hand but, with 60, 72, even 86 people onboard a small eight-meter inflatable dinghy, they were unable to prevent deaths. These large numbers of people, most of whom have never met before and come from different countries and speak different languages, means they often don’t even know how many are in the dinghy or what happens to a family member or friend.

Most recently, on Thursday (18.07) night a dinghy with 86 people onboard set off from the French coast. According to the Prefecture Maritime, the CROSS Gris-Nez tasked the Navy vessel P677 Cormoran to assist, but the people initially refused as they would have been taken back to France. At around 1am on Friday (19.07) the extremely overcrowded inflatable got into difficulty and the people then asked for help. When Cormoran’s rescue boat arrived, five people had fallen into the sea. They were immediately recovered, but when the rest of the people were being rescued one person was found unconscious inside the dinghy. He was taken to Cormoran but could not be reanimated onboard, nor by the medical team who evacuated him by helicopter. We now know he was a teenager from Sudan named Abdulaziz.

Slightly more than 24 hours earlier, on Wednesday (17.07) evening, a dinghy with 72 people shipwrecked on its way to the UK, approximately five miles north of Calais. According to the Prefecture Maritime, the dinghy’s sponson deflated and in a matter of minutes everyone was in the sea, many without life vests. A British Coastguard plane was observing overhead and the Cormoran, which had also been following this dinghy closely, launched its rescue boat. Both UK and French Coastguards immediately sent many rescue assets to the scene, including airplanes, helicopters and lifeboats. Despite the quick reaction, one woman from Eritrea died.

Less than one week before this, in the early morning of Friday 12 July, another dinghy shipwrecked just a few miles off of Cap Gris-Nez with over 60 people were onboard. The French safety vessel Minck observed its sponsons deflating and many people in the water. Again the Coastguard responded quickly, sending the Cormoran, a lifeboat, a helicopter and instructing a nearby fishing vessel to assist. Still, four people died in the incident. Identification is ongoing but it is understood they were young men from 4 Somalia.

We mourn those whose lives have been taken by this border – who are so young and have overcome so much before arriving to the North Coast of France. However, it would be a mistake to think about their deaths as merely tragic events. Nothing about them is inevitable and the shipwrecks are not caused by misfortune in an unforgiving sea. Instead, they are the outcome of a series of decisions made by the British and French states to enforce the UK’s border on the French coast and to constantly reinvest money and police resources to ‘stop the boats’. Under the rhetoric of ‘security’ and ‘saving lives’ governments have made crossing the Channel increasingly dangerous.

In the past twelve months, there have been more deadly incidents resulting from attempts to cross the Channel than in any previous year. Since August 2023, 32 people have now been killed and four people are still missing at sea from 14 separate incidents related to sea crossings, according to Calais Migrant Solidarity. Alarm Phone has attributed this to the intensified and often violent border policing on the French coast which has reduced the number of dinghies arriving to the beaches and which is creating chaos during launches. More dinghies are departing from France underinflated and overcrowded. Recently, a UK Border Force officer confirmed that their efforts to disrupt the supply of dinghies further upstream means the ‘loads are getting bigger’. The result, as we have seen in the last week, is that dinghies are failing more quickly with more causalities, as more people need to be rescued in each shipwreck.

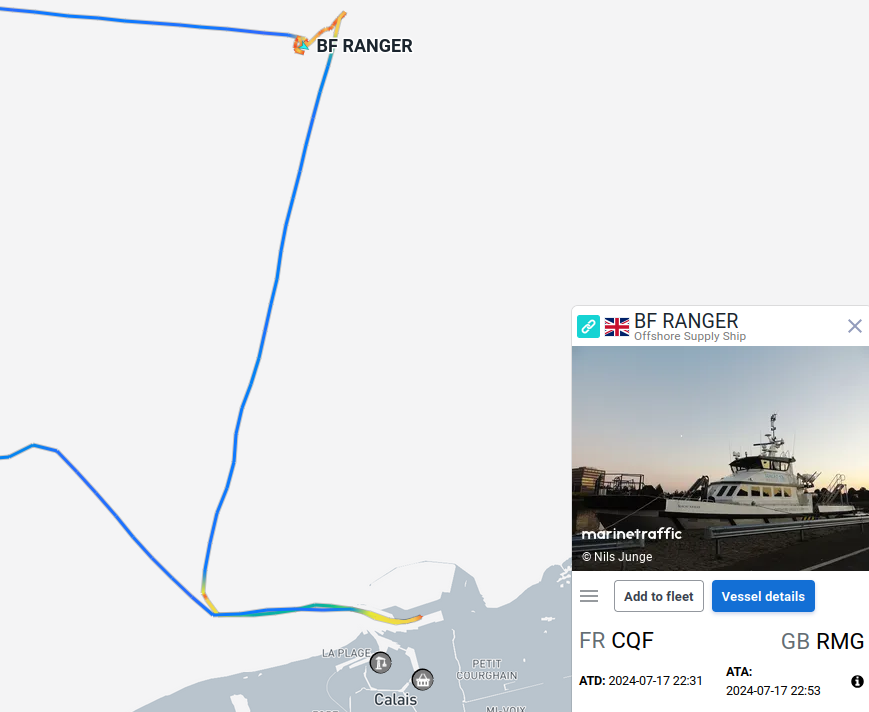

We were also disturbed to observe on Wednesday 17 July that the British Border Force Ranger entered the port of Calais to return its 13 survivors to France. While the incident did occur in French waters, previously survivors of shipwrecks rescued by UK vessels had been brought to Dover, as on 12 August, 2023. The requirement in the Nationality and Borders Act 2022 that asylum claims be made in a ‘designated place’ means that the UK Border Force officers onboard Ranger would have refused any asylum claims the people made. Those survivors, likely traumatised after the shipwreck, will now have to face the sea again on their journeys towards the UK.

AIS Track of BF Ranger from 17 August, 2024 showing where the rescue took place and then its movements to deliver the survivors back to Calais, France. MarineTraffic.

What has become clear in the last year is that the increased search and rescue resources and coordination cannot prevent deaths in the Channel. More rescue vessels and quicker responses have made a big difference in these recent cases, but are also obscuring the true nature of the problem. At the same time they are proclaiming to be saving lives by preventing dangerous departures, the UK and French governments are taking actions which are directly causing more death and trauma on the shore and at sea. The fact that in each shipwreck there are comparatively fewer deaths than in, for example, 2021 allows them to fly under the radar, even be ignored. We cannot allow shipwrecks and death to become normalised commonplace occurrences at this, nor any, border.