Painting by Amaya, a 10-year old girl from near Málaga whose mother is an activist. Amaya painted the boat being welcomed into harbour when asked: “What is important to you?”

Painting by Amaya, a 10-year old girl from near Málaga whose mother is an activist. Amaya painted the boat being welcomed into harbour when asked: “What is important to you?”

Introduction

There has now been a year of Covid-19 measures. They have been used by states to intensify repression against travellers, pushing them to take bigger risks on their journeys. Nevertheless the UNHCR numbers for arrivals in Spain in the first three months of 2021 show a slight increase in arrivals in comparison to the same period last year (2021: 6229 ; 2020: 5539 ; see Section 1). These numbers clearly show that neither Covid-19 nor repression can stop people from exercising their right to freedom of movement

What the numbers conceal are, firstly, the increasingly important routes from Algeria to Europe (see Section 2.7) and, secondly, cases in which people started a journey but were intercepted, went missing or were later found dead (Section 3). It is much harder to go beyond the UNHCR’s arrival statistics to create an accurate representation of who is on the move, where movement is happening and on what scale. We touch upon these hidden journeys in our daily Alarm Phone work. Sometimes people reach out to us, but we lose contact with each other and state organised SAR-operations fail to find them. One such case is AP127-2021, where the faint hope of news dims a little more each day (see Section 2.1). We hear about them from family members who reach out to us or to newspapers to report their missing relatives. This is what happened with a boat which left on 28 December from Dakhla heading for the Canary Islands. The families of the people on board are still looking for their loved ones. It also happened on 13 January when one of a group of friends went missing as he tried to swim into Melilla . We hear about them from our activist friends who try to identify the dead bodies that are washed ashore. But for many cases, we do not hear anything at all.

In this report, we bring together official figures, press reviews and Alarm Phone shift work with the analyses of travellers and activists living in or transiting through different parts of the Western Mediterranean region to give a multi-perspectival picture of recent developments and the effects of Europe’s racist policies on those directly affected by them. We aim to show what the statistics can never map: that behind each number there is a person with their own complex story; that, against all odds, people organise themselves to exercise their right to freedom of movement; and that the dead and the missing are mourned and remembered. (See Section 4)

These missing or dead people are all victims of a deadly border regime whose frontier is found in externalised border control and ever increasing repression against travellers in African as well as in European countries.

The situation on the Canary Islands is rapidly deteriorating. Poorly equipped camps, little hope for legal routes to peninsular Spain, deportations and other violent practices are turning the Canaries into an island prison – creating a situation not unlike that on the Greek islands in the Aegean.

The deliberate creation of such an environment, supposedly to deter other travellers from going there, is a scandal. So far, the European public seems not to have noticed the ongoing violence against travellers on this outpost of European territory. The Spanish state and the EU have chosen to make it hard for the press to report about the situation. They have, for example, denied journalists access to the camps. To work against that, we decided to include a more detailed account of the different islands and the situation that travellers face on each of them (See Section 2.1).

People who reach the Spanish enclaves of Ceuta and Melilla through irregular routes face a similar problem. They are denied a regular route to peninsular Spain. Instead they are trapped in the enclaves with little or no attention paid to their physical or mental needs. In that situation, you have no access to work, to schooling or to proper housing (see Section 2.3). Spain seems to be using the geographical and political specificities of both the enclaves and the Canary Islands as part of their strategy of restricting certain people’s movement. The linkage between the Canaries and the enclaves is further illustrated by the fact that deportations from the peninsula to Morocco which were previously done via Ceuta or Melilla, now, after the closure of the Moroccan land border with Spain, go via Gran Canaria (see Section 2.4). Furthermore, even people who are in the asylum procedure are prohibited from moving freely throughout Spain – a practice once again found to be illegal for by the Supreme Court of Spain.

Most of the tools of repression against travellers are the same, no matter which side of the border you find yourself on: racial profiling, illegalisation, raids, arrests, detention, expulsions, deportations, and the destruction of property or basic infrastructure.

In Morocco, for travellers residing in the north of the kingdom, arbitrary arrest and expulsion to the south of the country is systematic. The practice has recently taken an even more worrying turn (see Sections 2.2/5/6). In February, a gathering was organised in Rabat to denounce the “unbearable living conditions of migrants of sub-Saharan descent“. In December, AMDH (Moroccan Association for Human Rights) had pointed out that members of sub-Saharan communities “residing in large cities in the North and in the city of Rabat in particular are victims of arrests, a manhunt”. In Rabat, people are sometimes captured in the streets by people in civilian clothes, beaten up and handed over to the authorities. They are then kept for a few hours and expelled to cities in the south. In these areas, illegal detention has been observed. The AMDH reports the illegal detention of a group of sub-Saharan travellers (15 women, six children, and five Senegalese men) in Guelmime, southern Morocco for 23 days from 17 February. The Malian, Ivorian and Guinean detainees were then deported to their countries of origin.

The tools of repression used by Morocco are often funded by the Spanish state. This can be seen, for example, in the Spanish Ministry of the Interior announcement that they will fund Moroccan with 10 million Euros for border surveillance. At the same time, the Spanish search and rescue agency, Salavamento Marítimo, is woefully underfunded, inevitably resulting in more death at sea.

The expansion of the Eastern route from Algeria towards Spain (and the expansion in the central Mediterranean route from Algeria to Italy) shows that the great exile movement which started in 2020 is ongoing. Many Algerians are on the move to escape the post-Hirak society, the disillusionment and repression following the massive 2019 movement, as well as the social and economic impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic. The authorities attempt to prevent departures. The repression takes on a dizzying dimension when it is turned against sub-Saharan travellers in Algeria. Mass deportations and harassment of Black sub-Saharans are racist state policies and direct effects of the externalisation of European borders. Indeed, in addition to the criminalisation and repression of travellers (Algerian harragas and sub-Saharan travellers), the Algerian state is increasingly engaged in active collaboration with European states. (see Section 2.7)

But as travellers in the Western Mediterranean region are more and more pushed out of Morocco and Algeria by repression and are risking longer and longer journeys across the sea, networks of solidarity grow along with them. This became very visible in this year’s CommemorAction on 6 February, where different kinds of actions were organised in Morocco, Western Sahara and Senegal. (see Section 4)

Young boy posing at 6 February 2021 CommemorAction in Tangier. Source: Alarm Phone

Young boy posing at 6 February 2021 CommemorAction in Tangier. Source: Alarm Phone

1 Sea crossings and AP experiences

According to UN statistics 6,229 people arrived in Spain between January and March 2021. Over half of the new arrivals (3,360 people) travelled to the Canary Islands, while 1,791 people arrived on the mainland in Andalucia.

Alarm phone was called for help in the Western Mediterranean (WM) and Atlantic Ocean by 31 boats carrying around 676 people between January and March 2021. This is half the number of WM distress cases that Alarm Phone received in the three months previous, October-December 2020.

Of the 31 cases, 19 boats carrying a total of around 431 people arrived safely on Spanish territory. Around 16 boats landed in Andalucia and five in the Canary Islands. Yet freedom of movement continues to be restricted by Mediterranean authorities. Nine boats that set sail for Spain, returned to Morocco. Six of them were intercepted by Moroccan authorities and, in general, the travellers were returned against the wishes of the passengers. One boat returned autonomously back to Morocco and two boats were rescued in distress by Marine Royal. The fate of three boats remains unclear.

While Alarm Phone reported no shipwrecks in the first few months of 2021, five people died during their journey even though their boats were later rescued. Our peace, thoughts and solidarity are sent to the four Moroccan men who lost their lives on board a boat that was rescued by Marine Royal and to Cisse Adamo who fell from a boat that was later rescued by Salvamento Maritimo. May your souls rest in peace.

2 News from the regions

2.1 Atlantic Route

Crossings & Arrivals // Shipwrecks & Boats

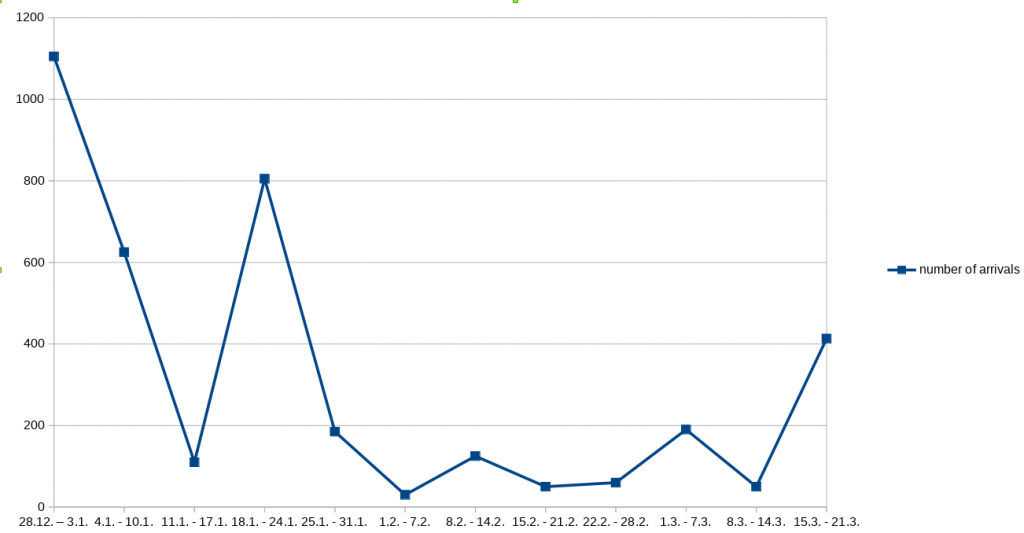

Despite the cold and harsh winter months, more than 3,300 people arrived on the Canary Islands by 28 March – a warm welcome to all these courageous travellers! The UNHCR’S per-week arrival statistics show a significant drop off in arrivals in February and early March. However, the last two weeks have seen arrival numbers rise again. Notably, 10 boats reached the Canary Islands in the last days of March, although there were three dead among the travellers. These boats carried travellers of Moroccan and sub-Saharan origin. One, carrying 37 people, was picked up 170 miles south of Gran Canaria – showing once again just how big the Spanish SAR zone in fact is.

Graph 1: Arrivals in Canary Islands, January – March 2021

Source: AP, based on UNHCR data

This drop-off in numbers from the last months of 2020 coincides with a variety of political strategies: the implementation of voluntary return programs, the complete absence of dignified housing conditions in the camps and the bar on Moroccan and Senegalese nationals travelling to mainland Spain – transforming the Canaries into an island prison. All these elements are designed to reduce the so-called “pull factors”. Whether this cynical calculation actually results in lower number of arrivals is difficult to judge. The drop-of might well be due to the harsh weather conditions in the winter months. Nevertheless, we should remember that only 1,626 arrivals were counted in the corresponding time period last year (Jan-March 2020), which is only half the number people who have made it to Europe this year.

Alarm Phone has assisted travellers in several cases, many of them resulted in BOZA (“Victory”, the word for successful arrivals in Bambara), thanks in part to the tireless work of the Canary Islands coastguards. In many cases, communication with them is friendly and constructive and we work with an organisation, the Salvamento Maritimo (SM), which takes its responsibility as a SAR organisation seriously. We see them doing their best to rescue one boat after the other, irrespective of the origins of the travellers. Until the end of 2020, the rescue crews on SM assets often consisted of just three members. With additional funding or 2.5 million Euros, a fourth crew member is supposed to be added. Although this is a very modest positive development, we, as Alarm Phone, believe this financial increase is ridiculous compared to the hundreds of millions invested in “border control” and attempts to restrict migration. We demand more money for Salvamento Maritimo, decent working hours for their crews, and say no to cuts – especially when it’s about saving lives.

Not all the boats we accompanied made it to the Canaries. Several were intercepted by the Moroccan Marine Royale. Sometimes the Marine Royale intervened in a situation of danger. One example occurred on 2 March 2021, when a boat got into distress 20km from the shores of the Sahara (Alarm Phone case 104-2021). In several cases we witnessed people dying during the crossing. Four travellers died on a boat carrying 34 people that had started from Dakhla on January 31. The survivors were rescued by Marine Royale after one week at sea (Alarm Phone case 54-2021). Another person drowned in mid-March, however 49 others survived the journey and were rescued to Gran Canaria (Alarm Phone case 113-2021). On a boat with 35 passengers one boy died on the journey. His boat spent five days at sea before being rescued to the Canaries, (AP case 011-2021). As his 12-year-old sister recounts, his body was given to the sea after his death. Another shipwreck, as far as we are aware, is yet to make it into the news. AP Maroc report that five people died on a boat that left Mauritania on March 3 before running into trouble. The 52 survivors were picked by the Marine Royale near the shores of Boujdour. As is often the case, they were then sent to detention centres further North for 10 days without receiving the medical and psychological care that they needed.

These are not the only tragedies. All in all, Spanish authorities have recorded 34 deaths on the Atlantic route so far this year. Of course, these are only the official numbers. As the example from Mauritania shows or the fact that Moroccan families are still looking for a boat that disappeared on December 28, it is certain that the death toll is higher. There are no doubt many more deaths which we will never know about. As we write, Alarm Phone is looking for another boat that seems to have disappeared (AP case 127-2021) into the vastness of the Atlantic ocean. It left Laayoune on 24 March, carrying 50 people. Our hearts and hopes are with them, but we fear the worst.

Apart from arrival numbers and the numerous shipwrecks, there are some noteworthy tendencies in the demographics of people crossing. In a boat that was intercepted by the Marine Royale in mid-January, half of the travellers were of Egyptian and Yemeni origin. We did not witness people from these countries of origin taking this route to Europe so far. The past months have also seen an increase in young travellers, especially minors. Overall less women attempt the western routes than the crossings in other regions. Only 5% of all arrivals to Spain are women. However, on the Atlantic route, there are often boats with very high numbers of women. For example, in mid-March Salvamento Maritimo was searching for three boats that were in large part occupied by women.

Another change concerns departures from Senegal, Alarm Phone activist B. explains:

“In this part of 2021, we note a decline in boats leaving from Senegal, because the Spanish state has sent more border patrols to Senegal in order to further secure the border and to intercept migrants at their point of departure. Furthermore, people are criminalised, charged with being “responsible” for the boats that leave.”

Yet the Senegalese youth still suffer from a lack of opportunities and the detrimental effects of the Covid-19 crisis, the very things which prompted many to leave in the first place. Demonstrations and protests in early March 2021 left 14 dead. (Source: Alarm Phone)

Interceptions at the point of departure also happen in Mauritania. On 12 February, for example, 52 travellers were intercepted by the Mauritanian gendarmerie.

Situation on the Canary Islands

“Where can I get a bus to go to France or Italy?” was one of the first questions asked by travellers on arrival on the shores of the Canary Islands in November. Months later, people are still stranded on the Islands. There is still an environment of uncertainty, a lack of information while conditions in the recently opened camps are harsh . Still, in the imagination of many travellers, Europe is seen as a safe place. Welcome to Canary Islands, a territory almost beyond the periphery of Europe and an enclave on the deadliest migration route of 2021.

Plan Canarias

The Plan Canarias is the local emergency framework, funded by the EU, it is based in the coordinated management of seven temporary, emergency reception centres. These contain 7,000 bedspaces and are distributed across Tenerife, Gran Canaria and Fuerteventura. By 2022, authorities are expecting to move people from these reception centres to long term facilities, showing a clear intention to keep on using islands as part of their inmobility strategy.

The Camps in the Canaries

Tenerife

In Tenerife there are two reception camps. First, Las Raices, managed by the NGO ACCEM and funded by the Spanish Ministry of the Interior and the EU. There are currently 2,000 men living there. 49 of them are unaccompanied minors. It has been the most controversial camp so far because the living conditions are so harsh. The facility is located at an elevation of 1,000m in a rainy area. The inhabitants live in big tents and the food provided is poor. The whole situation has led to riots and hunger strikes, followed by police abuse and detentions. In total, there have been four hunger strikes registered this year. The last was on 1 April, when Morrocans were protesting because they are not allowed to travel to the mainland.

Hunger strike attempted by Morrocan travellers at Las Raices camp, Tenerife, demanding their transfer to the mainland. It lasted one day. Source: Asamblea de Apoyo a migrantes de Tenerife. 1.04.2021.

Hunger strike attempted by Morrocan travellers at Las Raices camp, Tenerife, demanding their transfer to the mainland. It lasted one day. Source: Asamblea de Apoyo a migrantes de Tenerife. 1.04.2021.

The second camp, Las Canteras, is managed by the IOM and is already at full capacity. It harbours around 1,300 people on an abandoned military complex. There are only two lawyers and psychologists to assist the entire population.

An alarmingly high number of minors are reported to be living in these two camps, although there is no provision for children and adolescents. Regardless, the authorities even organised a relocation plan for 100 unaccompanied minors from a hotel to the camps. Some minors refused to go to the camp and slept in the streets as a form of strike supported by activists. Their demand: appropriate protection.

Despite all this, no minor has been able to lodge a request for asylum as a minor. This highlights the abserce of legal assistance and information about asylum. Indeed, the Spanish Ombudsman recently published a report regarding the lack of translators and legal support. All of this perpetuates the current state of immobility.

One programme that is functioning on Tenerife is the voluntary return program of the IOM. According to travellers’ testimonies, it has been accessed largely because of the state’s refusal to allow transfers to mainland Spain. It has also been used by people who want to be back in their origin countries for Ramadan. Some people have even decided to return by their own means. There are in fact some transfers to the mainland. People are screened by the authorities. If you are found to be a ‘person in particular need of protection’ (persona con necesidades de protección), you become eligible for relocation. The theory is that particularly vulnerable people fall into this category and that is why they are allowed to move. In reality, the screening is done by nationality. Being from Mali, the Gambia, Ivory Coast or Guinea are some of the criteria you need to meet to be put into this privileged class. People from Senegal or Morocco are not classed as in particular need of protection. It is noteworthy that nationals from countries where Spain has a return agreement are not deemed to be vulnerable. Where no such agreement exists with your country of origin, you have a chance of reaching continental Europe. It might be thought that the real aim of the policy is to clear the islands of travellers who are not tourists. The ideal scenario, from the Spanish state’s point of view, is to deport you to a country in Africa. Where that is not possible, they will let you off the island by taking you to the peninsula. It should be noted that the majority of such people on the islands are from Senegal or Morocco.

Gran Canaria

The Colegio Leon is the longest running housing facility for people who make the crossing to Gran Canaria. It is managed by the religious NGO, Cruz Blanca, and located at a primary school in a working-class neighbourhood. Despite the presence of and harassment from the far right when the project started, the travellers staying there proactively engaged in the neighbourhood and helped maintain green spaces in the surrounding area. This was useful and well received by the neighbours, who now support their struggle.

There is also a complex on an industrial estate. The site has been loaned by the bank, Bankia, and managed by the same NGO as the Collegio Leon. It is expected that about 500 people will be transferred there. However, this installation opened in the last week of March and so far there has not been information about the conditions at the site.

An abandoned military complex, Canarias50, managed by the Red Cross is also used to house people on Gran Canaria. It has a capacity for 1,300 people. So far, there have been several floods and a group of 64 people went on hunger stike for a few days on 6 February. They wanted to raise awareness about the situation at the camp and demanded that they be allowed to exercise their right to continue to mainland Europe.

Unfortunately there has been some fascist activity. At the beginning of the year the Red Cross advised all travellers accommodated in the camps and hotels to avoid going outdoors because of the threat of right-wing violence. In response local activists and networks worked to create welcome by supporting people who had made the journey and advocating for them.

Those who were hosted in the hotels feared being transferred to Tenerifa rather than mainland. Indeed many people have refused to be transferred. They are currently without a home and their asylum process is on stand-by. According to activists and the Red Cross, it is estimated that around 2,000 travellers are currently living on the streets of an island with 850,000 habitants. In response, neighbours have created the network “Somos Red”. It provides food, donations and social support, as the council is still refusing to deal with this situation.

Fuerteventura

On Fuerteventura the Red Cross run El Matorral camp on the site of an abandoned detention centre. “We did not escape our countries to be imprisoned” was the common refrain of the strikes that happened throughout March. People on the move want to be able to exercise their right to travel to mainland Spain and continue their journey. People want to be reunited with their families and loved ones. People came here to find a home and decent employment. People have the right to seek and find freedom and peace.

***

Plan Canarias is nothing more than a racist tool of the racist institutions that are the European Union and the Spanish state. They deliberately and openly use the abuse of Africans as a “solution” to the non-problem of migration. By trapping people on the Canaries, providing sub-standard living conditions and denying resources to people on the move, the State wants to send a clear message: no matter who you are, if you are from Africa, you do not belong in Europe.

The Canary Islands are becoming the antithesis of the “No-More-Morias” slogan of the latest European pact on migration. The Plan Canarias reproduces the whole set of detention and immobility policies which created Moria in the first place. Unsurprisingly, it is not difficult to find similarities with locations such as the Aegean Islands. The Canaries belong to an international, interlaced struggle of people on the move. Those moving, activists and civil society are already wondering to what extent any of the islands will become the “Atlantic Lesvos”.

In addition, the president of the Canary Island’s Parliament, Antonio Morales, has rejected the Plan Canarias. He accuses the central government of heaping pressure on Canarian society by leaving them alone to deal with the consequences of decisions taken at European levels. However, the European commission insist that the no-relocation policy is a decision taken by the Ministry of Internal affairs, and not at a European level.

Nevertheless, there is an urgent need to open a debate around why people migrate and how the EU responds to the phenomenon. We should also be talking about the role of the European Union in the deterioration of the social conditions in the countries of origin. Western society struggles to acknowledge the ongoing significance of its colonial legacy. It is also a society in which fundamental ethical impulses, such as the impulses to hospitality and solidarity, are outlawed. It is in this context that the Alarm Phone wishes to remember that the Canaries are not an isolated phenomenon. They are part of a whole network of resistance and struggle. We stand in solidarity with people whose freedom to move is constrained because of their racialisation. We do this not only by running a hotline for people in distress, but also by working in an international struggle for social justice and freedom of movement. In a system that was never meant to protect those pushed to the margins, we call for the creation of strong communities which ensure that no one gets left behind.

Situation in Western Sahara and Southern Morocco

The dramatic increase of departures towards the Canary Islands in 2020 has of course had consequences in the countries of departure. One of these is the securitisation of the shores of Western Sahara. Alarm Phone activist A. explains that more and more control posts are being built along the coast, particularly on the beaches used by travellers for starting their journeys.This observation is in line with the announcements by the Spanish ministry of the Interior at the beginning of this year to send another 10 million euros for border surveillance.

Guard posts at the coast for border surveillance, 30km away from Laayoune. Source: AP Maroc

Guard posts at the coast for border surveillance, 30km away from Laayoune. Source: AP Maroc

The other main development resulting from the steep jump in departures is an overall deterioration of the human rights situation. This phenomenon is not recent, as A. states:

“For many months now, migrants living in Laayoune are the victims of arrests and manhunts. This happens in the form of controls that target the sub-Saharan community only. Sub-Saharans are captured and deported into areas far away from the cities.”

Reports published in the beginning of 2021 by human rights organisations show an alarming picture. The Covid-19 crisis has been used as a pretext to harass sub-Saharans by arresting and detaining them for an arbitrary number of weeks or months, without any legal basis. Moroccan and Saharans on the move and their communities are also severely affected by the repression as well as the pandemic. Because of Covid-19, many have lost their jobs and what opportunities they might have had, especially in Western Sahara and the South of Morocco, where the economic situation is less stable than maybe the case elsewhere.

2.2 Tangier and the Strait of Gibraltar

Police raids in Tangier: a brutal routine

Although the Tangier Med port complex north of Tangier in 2020 became the “first port of the Mediterranean” by volume of cargo handled, the city and its environs remain an extremely hostile place for people hoping to travel.

The situation in the city of Tangier remains very difficult for people on the move. As local activist J. explains, “the city is still under strict Covid-19 restrictions. The security has increased in the city and its surroundings, so the migratory flow has slowed down”. According to him, there was an increase in arrests of illegalised travellers by the auxiliary police in the city in January. He says, “they drive people to the edge of the city or to Assilah [south of Tangier], in order to destabilise them.” Frequent arrests are made in the neighbourhoods where sub-Saharan communities live. These can and do occur in the very homes that people live in. Alarm Phone activists in Tangier report that sometimes sub-Saharan women and their children are arrested while they are begging for food in the street.

On 2 March, local contacts reported police raids and arrests in the city. At least 25 people, including five women, were arrested in the Medina (the old city). The police entered several sub-Saharan Africans’ houses and made all the people go outside. They then arrested them and brought them to the edge of the city. On 13 March, 17 more people (including two women) were arrested on 13 March. This also occurred in the Medina. The ongoing “Programme of rehabilitation of buildings in severe disrepair” (Programme de réhabilitation des bâtiments en état de délabrement avancé) in the old city is doubles up as a perfect excuse for local authorities to ramp up the pressure on Black sub-Saharan communities. People are turfed out of their homes under the pretext of renovating ruined buildings. According to our contacts on the ground, further raids were made on 13 March in the neighborhood of Mesnana, close to the university. 13 sub-Saharan Africans (including two women) were arrested.

Moroccan auxiliary forces also regularly conduct raids in the forests near Tangier. These are places where travellers live, hiding as they attempt to reach the Spanish coast by crossing the Strait of Gibraltar. The arrests often result in the people arrested being expelled from Tangier to the south of Morocco. Victims of such practices are likely to find themselves in the cities of Tiznit, Marrakech or Errachidia.

Living conditions are tough for the illegalised travellers courageous enough to stay in Tangier, especially in Covid-19 times. It is difficult to access housing and other basic necessities. The same is true of access to healthcare. In February, we were informed of the death of three men from the sub-Saharan communities, two from Ivory Coast and another one from Cameroon, because they could not get proper medical attention. Our hearts and thoughts are with the family of the deceased.

“Very few manage to touch the water” (J., AP Tangier activist)

In the last three months, Alarm Phone was not involved in any case starting from Tangier. However, we know from Helena Maleno Garzón’s Facebook page that there were at least two successful crossings of the Strait of Gibraltar. One was on 16 March, with one Maghrebi person on board and a second on 26 March, with one Moroccan and nine sub-Saharan travellers. Both arrived in Algeciras. In Spanish media, there was also a reference to a rescue in the area on 17 February.

In summary, what was said in our most recent reports still stands. The brutal security, controls and arrests in the city of Tangier and its surroundings make crossing the Strait of Gibraltar, at least for sub-Saharans, very difficult. As a result people are more likely to try the dangerous southern routes.

8 of March – Event in Tangier

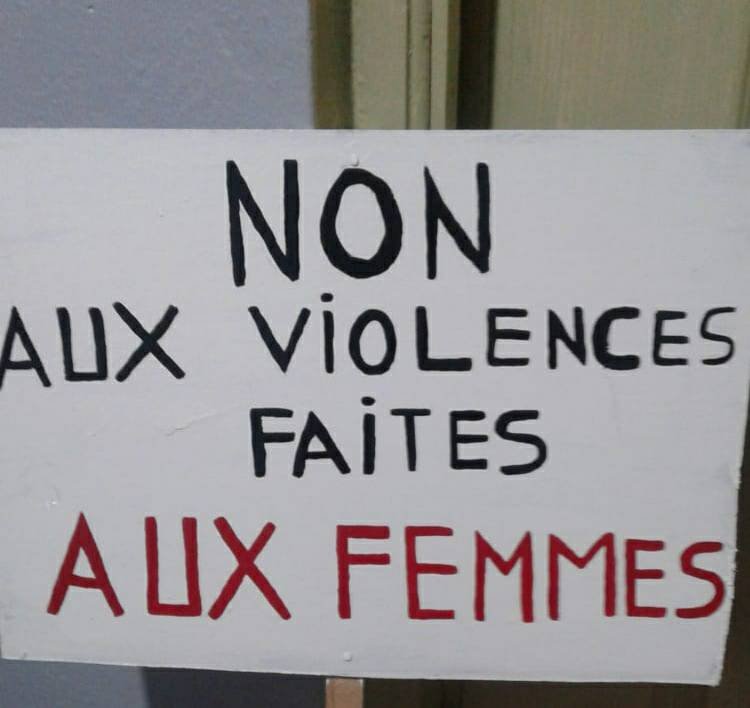

On 8 March, International Women’s Day, women gathered in Tangier to celebrate themselves and their victories and to reflect on their fight as women on the move against a deadly, racist border regime. As Covid-19 restrictions did not allow for them to take to the streets, they hosted a discussion on Alarm Phone work, interviewed each other and ended the day with a meal together. After a day of solidarity and strength the women proclaimed:

“On this international day for the feminist struggle we cry out against discrimination and violence against women, and this day has been a success!“

8 March 2021 in Tanger: Sign “Non aux violences faites aux femmes” (“No to the violences against women”). Source: Alarm Phone

8 March 2021 in Tanger: Sign “Non aux violences faites aux femmes” (“No to the violences against women”). Source: Alarm Phone

The women also got together and wrote the following manifesto:

“Despite all the risks we face, every day, we, women activists, are on the ground. And this is what gives us the strength to continue our fight as women and to fight for the people’s right to freedom and for their well being. So we launch a solemn appeal to our leaders to respect international agreements and give more consideration to the struggling women who are there for the good of this world.

Our action [the 8 March event] is well received by our sisters who suffer at these borders and wait to travel. It allowed us to think again about how and how many people die every day at the borders and that the fight must not stop. ‘La main sur le coeur.’ ” (‘Hand on heart’)

2.3 The enclaves: Ceuta and Melilla

Although the numbers from the UNHCR and the numbers of the Spanish Ministry of the Interior differ, set against the first three months of 2020, we can see a clear decline in arrivals to the enclaves by land but an increase in arrivals by sea in 2021. This mirrors the overall downward trend in arrivals to the enclaves over the last few years.

Arrivals via sea increased, according to Ministry of Interior, by 223.8% in the first two months of 2021. A big factor in this was more people trying to swim around the fences into the enclaves. We have also seen an increased use of kayaks and inflatable dinghies as a way to get over the border.

Every one of the travellers taking this route is risking their life to exercise their right to freedom of movement. Especially in the harsh conditions of the winter months, this route kills many people trying to leave or enter the Spanish enclaves. Many try to cross alone, so it is reasonable to believe that there are many unrecorded cases. one case, on 13 January 2021, we were alerted to the disappearance of two people who, along with another friend, had attempted to swim into Melilla but never arrived. In other cases, like that of Ayoub Fakhari and Dahani Bilal, who went out on 29 January 2021, the family of the disappeared turns to the newspapers to report a missing person.

Getting into the enclaves via land has recently become more difficult than ever before. A large part of the blame for that falls on the intense repression of people trying to move on the Moroccan side of the fence. This, as noted in section 2.1, is funded by the Spanish state. Another important factor is the installation of inverted tubing on the fence between Morocco and Ceuta. Despite that, people organise themselves. There were three big jumps in the first three months of 2021:

On 19 January 2021, 150 people tried to jump the fence and 87 made it into Melilla.

On 8 March, 59 people managed to jump the fence into Melilla. In the following days there were many raids on the Moroccan side of the fence.

On 30 March, 100 people tried to jump the fence into Melilla. 33 managed to cross.

– Congratulations to the Bozards!

Smaller groups also managed to cross the fence into Ceuta. To do so, they had to overcome the various fences on the Spanish and Moroccan side, equipped with barbed wire and the newly installed inverted tubing: on 08 and 17 February a total of 13 travellers made over the barriers, and on 01, 05 and 12 March total 11 people entered Ceuta this way.

In the ongoing legal debate about the legitimacy of hot deportations at the border fences of the enclaves, there was an intervention from the European Commission for Democracy. They criticised the ruling of the Constitutional Court of Spain by which rejections at the border are allowed under certain conditions. In particular one of the conditions for allowing immediate return was the possibility of claiming asylum at regular entry points to the enclaves. The European Commission for democracy pointed out:

“Police officers intercepting migrants at the border fence may proceed in a different manner, if, in the circumstances, they see that those specific aliens have cogent reasons for not using ordinary entry points for asylum-seekers.”

Furthermore, many people try to continue from the enclaves to peninsular Spain by boat or by hiding in trucks or containers. In one case, 41 travellers were intercepted by the Guardia Civil in the port of Melilla, some of whom had even gone so far as to hide in broken glass containers and toxic ashes. This shows just how desperate the situation is for many travellers in the Enclaves. Underfunded camps, no access to schooling for minors, no access to basic infrastructure in the CETIs for people who are newly arrived (although the CETIs are not overcrowded at the moment), authorities that are ridiculously slow in implementing Supreme Court rulings for ‘legal roots’, are all factors which had turned the enclaves into open-air prisons for travellers, even before closed its border with Spain.

2.4 Al-Hoceima

The current situation in the Rif region is complex. There is a lack of infrastructure. Hospitals and universities are scarce. Furthermore, there is no investment in industrial development and youth unemployment is high.

In addition, there is no real freedom of speech, as was shown but the vicious repression of the Hirak movement. In 2017, protesters demanded freedom and civil rights for the citizens of the Rif region. One of the most prominent leaders of this movement, Nasser Zefzafi, to twenty years. There are numerous examples of Moroccan state censorship. For instance, in 2018 a young man took to social media to condemn the murderer of a migrant woman by the Marine Royale. He was imprisoned for two years. Despite the protests for freedom and civil rights, nothing has changed. As a result, activists and civilians head to Europe, mainly via Spain, from the Rif in search of a better life and/or .

According to our knowledge, in 2017 the number of Rifians arriving in Spain was high. Currently this number has decreased because interceptions by the Marine Royale (the Moroccan Navy) have increased. The level of militarisation has not changed since 2017, but the governmental strategy is different according to locals. They argue that in 2017, there was a political fight led by the Rifian working class, therefore, it was in the government’s interest for the protesters to leave the country. Now that a large number of pro-freedom partisans have left, the government is happy to utilise its forces to restrict people’s mobility.

Covid-19 has had no effect on the number of boats leaving the shores of Al-Hoceima. Boats leaving from there head for Málaga and Montril, Granada. Rifian migrants normally organise themselves in small groups and travel by dinghies or on jetskis. A small number of sub-Saharan migrants leave from Al-Hoceima for Europe. They organise bigger groups.The journey is normally between 15 and 24 hours depending on the sea and the conditions of the boat.

According to our own research, in January, 185 Rifians and 48 sub-Saharans arrived in peninsular Spain. In February, at least 73 Rifians arrived in Spain: 46 on 14 February, and 27 on 18 February. To our knowledge, in March, 112 people from Rif have arrived in Spain. Here are two examples of these cases:

- On 14 February 2021, two boats that left from Al-Hoceima with 46 people from the Rif were rescued by Salvamento Marítimo near the shores of Motril. However, when they arrived in Motril, they realised that two people were missing.

- On 24 March 2021, 10 people from the Rif arrived in Motril. They had set out from Al-Hoceima

Many people have disappeared along this route. During the period between January and March, we know from local sources of missing who left from Al-Hoceima. Furthermore, according to our research, 7 people have died in these 3 months when travelling to Spain from Al-Hoceima.

In the last three months the Alarm Phone dealt with 11 cases with a total of 115 people who departed from Al Hoceima. Two boats were intercepted by the Moroccan Marine Royale and the others were rescued by the Spanish Salvamento Maritimo.

Development in new deportation routes

In these three months there has been a change in the policy of deportations from Spain to Morocco. Whereas it was a usual practice to deport Rifians from the peninsula (Madrid-Barajas) to the enclaves of Melilla and Ceuta and then onto Morocco, now, in the context of the pandemic and with the sea routes closed, a new route has been opened with regular flights along the route Madrid – Las Palmas (Canary Islands) – Laayoune (Western Sahara).

The deportations started again at the end of December. We have been informed by families that in January and February Spanish authorities deported two groups of people (8 people and 13 people) from the airport of Barajas (Madrid) to Las Palmas and then to Laayoune. Both groups were made up of inhabitants of the town of Guersif in the Eastern Rif region. Afterwards there were more deportations of Rifian people who were in the Centre of Internment of Foreigners (CIE) of Aluche in Madrid. In February, three Rifians who were in the CIE of Murcia received an expulsion order. They were transferred to Madrid, where they had to board, escorted by several policemen, a flight to Gran Canaria and from there they were flown in another plane to Laayoune. Both flights were operated out by Royal Air Maroc, the Moroccan national carrier.

The reason for the deportations from mainland Spain via the Canary Islands is not yet clear, but anyone who arrived in Spain from the Mediterranean coast of the Rif and is then brought to Laayoune has to travel more than a thousand kilometres to reach their homes in the north.

2.5 Nador and the forests

During the period covered by this report, Alarm Phone was only alerted to five cases in the Nador region. Two of the boats eventually rescued to Spain (27 January, 35 Moroccan nationals and 13 February, 38 Moroccan nationals from Arekmane). One boat was intercepted by the Moroccan Marine Royale (3 February, 45 Moroccan nationals from Bouyafar). On 10 January one boat initially carrying 36 passengers left Bouyafar and then went missing. We have to assume that the travellers are lost at sea. As already mentioned in Section 2.3, on 13 January, we were alerted to three nationals from Chad who tried to swim two swim to Melilla from Beni Ansar. One of them was rescued, but the other two remain missing.

Another tragedy happened on 7 January, when only 21 travellers could be rescued from a boat that had set off with 31 passengers from Arekmane/ Nador. Seven bodies were recovered from the sea. The others remain missing. One of the people who survived the tragedy was eventually hospitalised, but not before enduring three weeks of detention in Arekmane detention centre. The AMDH – Nador condemn his detention. They point out that it was without any juridical base and, therefore, illegal.

Arbitrary detention and the criminalisation of migration is a growing risk for travellers in and around Nador. In 2020, Moroccan forces claim to have arrested 466 suspects connected to 123 networks involved in human trafficking. In previous years, individuals have faced prosecution on these grounds without adequate legal representation or an interpreter present. In some cases, they have been condemned to up to 10 years of detention. The Kingdom’s attempt to repress irregular migration continues in 2021. On 9 February, the Moroccan authorities conducted large raids in several warehouses in and around Nador and arrested 16 persons (one Sub-Saharan national, 15 Moroccan nationals). They are accused of facilitating irregular migration, as well as human and drug trafficking. Among other things, the authorities seized 26 rubber dinghies and 35 engines.

Arbitrary arrests of sub-Saharans in the streets of Nador city continue. One such incident was reported by AMDH – Nador. On 19 February, police, the Moroccan auxiliary forces and other security officials were scouring the streets to arrest travellers who had come down from the forests to ask for help or to seek shelter.

As our local Alarm Phone groups observed, between the 22 January and 21 February there were 105 people arrested in raids in the forests of Nador. They were all brought to the now abandoned ‘colonie de vacances’ in Arekmane. The site, which was previously used for children’s holiday activities, has been turned into a makeshift detention camp. All of the arrested people were forcibly taken to the south of the country where they were abandoned.

Travellers who are arrested in and around Nador are generally illegally imprisoned in this detention centre. People who live in the forests around Nador and who have reached out to Alarm Phone have told us of other cases where people are kept in ‘deportation cells’ in Nador city. The Nador section of the AMDH reports that after detention lasting up to 3 months, travellers risk deportation to their countries of origin. this is especially true of nationals of Mali, Ivory Coast, Guinea, Burkina Faso, Cameroon and Ghana. There are close relations between the embassies of those countries and the Moroccan government. Others, such as nationals of Congo, Gabon or Togo, are, for the moment, not being deported. They are generally expelled from the city to the interior of Morocco.

Around 10 March, for three or four days, a large operation in the forests around Nador was carried out by Moroccan troops. They destroyed much of the crude basic infrastructure that travellers had built for themselves to survive in the makeshift camps whilst they wait for their chance to cross to Melilla or to mainland Spain. The forests around Nador city are an ongoing battleground and raids by the authorities never cease. They only vary in frequency and scale. The operations mid-march were large-scale and targeted all of the different forest camps at the same time. they led to a large number of arrests. The raids coincided with the visit of an official representing the Director General of Immigration and Borders of the Moroccan Ministry of Interior, Mr. Zerouali. They were conducted immediately after some 59 travellers successfully jumped the fences of Melilla on 8 March (see previous section).

One of the few people that managed to escape reported to Alarm Phone:

“The whole forest in general, they broke and burned at the same time, it becomes very, very difficult. They broke everything, everything. They took with them even all the women who were there, with the children. It’s not easy, it’s not very easy. It’s all over the forest. They piled up [the things they collected in the camps] in the open spaces where it [the fire] couldn’t attack the trees. They burned blankets, water cans, pots…it [these things] equals a lot of walking, these are things that people walked [worked] a lot for. And there are several [areas of] fightings, even in very remote areas. At the moment we know of 38 women and children who are being deported, along with 2 men who were the fathers of the children. The rest of the people [that they caught] are locked up now, and what will happen to them becomes a political issue. People are suffering. People are shedding tears. “

The Moroccan forces burning down piles of belongings. Source: Alarm Phone

The Moroccan forces burning down piles of belongings. Source: Alarm Phone

The Moroccan Forces raiding the forests. Source: Alarm Phone

The Moroccan Forces raiding the forests. Source: Alarm Phone

“I really ask people in the world to continue to struggle with us, it’s not really very easy. The situation is becoming critical and also things [migration routes] are blocked. But we know that the migrants will always be there. Patience is the greatest strength of migrants. To be patient is also to be fed in spirit. We know that we will reach the goal. All those who are there for the crossing, all those who are there to fight for the freedom of movement, all those who are there to fight for the migrants, all the NGOs, all the partners, all the activists, the fighters for migration, lets stay courageous never give up, let’s continue always in the same struggles, with the same fights, with the same goals, and we hope that [one day] there will be change.”

As our local contacts report, the police forces return to the forests at the end of March. We do not yet know how intense or frequent the current wave of raids will be.

2.6 Oujda and the Algerian borderzone

In the streets of Oujda, the arbitrary arrests of people from sub-Saharan communities continued during the first months of the new year. In each case, those arrested were released after a few hours of police custody. We are aware of the following arrests: 9 January (7 people), 9 February (25 people), 12 February (45 people), 23 February (23 people, including a minor) and 12 March (12 people, including a woman). The harrassment of sub-Saharan women who ask for help at roundabouts is also still ongoing. The women arrested are held at the police station for three to four hours and are then released.

Furthermore, measures taken to prevent the spread of Covid-19 going and major challenge for people on the move. There are still no assistance programmes for this group of people and what food is provided by NGOs is far from sufficient.

The border crossing between Maghnia and Oujda – its counterpart on the Moroccan side – remains one of the most important migration hubs in North Africa, but the European Union’s policy of externalising its border has resulted in the “securitization” of choke points on migration routes. learned that on 9 February 2021, a total of 12 people were arrested in Maghnia in Algeria and deported to the border with Niger. Additionally, on 25 February, a migrant camp was destroyed by Algerian forces in the forest near Maghnia.

At the Al Arja border area near the Moroccan town of Figuig border policies damaged the lives of the settled population. On 1 March Algerian forces ordered local farmers to abandon their land by 18 March. The land had been owned or leased by these farmers since colonial times and was being used to cultivate dates and olives.The Algerian authorities used a border demarcation agreement of 1972, validated in 1992, to claim the territory as Algerian. Despite many demonstrations, protests and talks the farmers had to vacate their land by the deadline. Shortly after the eviction, Algerian military tents were spotted on the appropriated territory. The former landowners had no knowledge of the governments’ agreement and were taken completely by surprise by the expropriation. Some farmers were able to salvage some of their crops and other property. They took what they could to Figuig where most of them reside. Tragically, . The Moroccan authorities responded in the evening of 16 March by indicating that these measures are temporary. Some solidary initiatives and lawyers will work on the case to support the farmers.

2.7 Algeria

Algerian nationals continue to leave the country in great numbers

The widespread disillusionment experienced after the failure of the Hirak movement as well as social and economical impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic, has led to a large number abandoning Algeria. This has been dubbed the ‘Great Exile Movement’. It began in 2020 the first few months of 2021 show that it is ongoing. According to UNHCR data, in the period January 2020 to February 2021, Algerian citizens comprised the second largest group by nationality of among Mediterranean arrivals to Europe. The biggest group by nationality were citizens of Tunisia. Spain remains the favoured destination of the harragas. A record 11,450 Algerian nationals reach Spain in 2020. Departures places include the coasts of Oran and Mostaganem. People leaving from there are heading for the shores of Almeria and Murcia or, in a recent development, for the Balearic Islands. But travellers use the central Mediterranean route to Italy as well. According to the annual report of the Italian Ministry of Interior, 1,458 Algerians reached Italy by sea between 1 January and 24 December 2020.

As mentioned in our previous regional analysis, the Algerian authorities have reacted by launching operations to increase interceptions. In the first weeks of this year, the Algerian government boasted that they intercepted 8,184 people in 2020. The authorities are obviously continuing in this vein. From 1 January to 19 January 2021, the Algerian authorities announced the interception of 153 people who made the attempt to leave Algerian shores.

The month of March was also particularly dense in terms of crossings and crossing attempts. In early March, 115 Algerians left the coast of western Algeria in Go Fast boats. Between 10 and 16 March, the coastguards of the provinces of Chlef, Mostaganem, Oran and Ain Témouchent (West Algeria) intercepted 99 harragas, including 18 Moroccan citizens. The Algerian coastguards and the gendarmerie regularly dismantle networks of smugglers in the regions of Oran and Tipaza.

Nevertheless, according to the journalist Jean-Pierre Filiu, this increased securisation and control of the Algerian coasts cannot hold back the exile wave that is growing in Algeria as a direct result of the repression of the Hirak protest movement. As he writes, “the wave of popular protest of the Hirak movement had, in 2019, led to a dramatic decline in illegal emigration of Algerians to Europe, so much that the youth, who until then lacked prospects, believed they could find their place in a country freed from the Bouteflika presidency; this positive trend was reversed in 2020, when Abdelmajid Tebboune, the dubiously-elected head of state, stubbornly re-established the political status quo.”

Crossings

Alarm Phone has been involved in eight cases of boats leaving the Algerian coast. Two of them were boats heading for Italy. All of the Western Mediterranean cases managed to reach Spain. We know that many other boats also made it to the Spanish shore in the last three months. On 17 February, seven boats carrying 97 harragas, including four women and several minors, were rescued off Murcia (Spain) by the Spanish search and rescue agency Salvamento Marítimo (Source: Spanish newspaper La Razon). Since the beginning of 2021, 758 Algerian nationals made it to Spain. They make up 61% of all recorded arrivals so far this year. People of other nationalities have also made it to Spain from Algeria. These include nationals of Morocco, Guinea, Mali, Bangladesh, Egypt and Syria.

Some boats do not make it. In the past three months, we were informed about a number of shipwrecks of boats which had left Algeria (see section 3 “Shipwrecks and Missing People”).

Notably, Alarm Phone receives frequent calls from Algerian mothers, brothers, sisters and cousins looking for their relatives.

Security reaction tightens border controls in Europe

The volume of departures by Algerian nationals led, at the beginning of this year, to a security response from European states, particularly France.

In January, the country decided to close fifteen crossing points with Spain. The prefect of the Pyrénées-Orientales region, in South West of France, justified this decision by saying that “thirty to fifty people have been stopped every day in an irregular situation since November.” The National government asked for a physical closure of these roads. This was carried out by the local prefecture who placed heavy concrete blocks across the road. The installation of these roadblocks is for an “unlimited time”. The French government seemed particularly disturbed by the fact that so many Algerian nationals were moving from Spain to France. According to the Algerian daily newspaper Echorouk, a member of the French Parliament declared on 18 March that “a massive influx of harragas from Algeria, to Spain and the pressure they exerted have led France to close fifteen crossing points at the Spanish border“. Moreover, the French Minister of Interior has explicitely targeted Algerian and Moroccan unaccompanied minors in France, expressing his intention to expell them. According to him, they have “settled in massive numbers” in the city of Bordeaux, South West of France, engaged in illegal practices and disturbed the tranquility and security of citizens.

In addition, the Algerian state has, in the past few months, collaborated very closely with the Spanish state. At the beginning of February, an Algerian official declared that the country had agreed to accept the return of its nationals who entered Spain illegally. So far, this agreement has resulted in the announcement of plans for the roundup and expulsion of Algerians living in Spain. These operations are scheduled to be carried out in the coming months. On 2 March, officials of Algeria and Spain met again to discuss the phenomenon of the harragas.

Other countries have also shown their eagerness to constrain the arrival of Algerian nationals to their territories. At the end of March, the daily El Watan, reported that the Swiss Minister of Justice and Police made an agreement with the Algerian state for the forced repatriation of 600 Algerian nationals living in Swiss territory.

Racism and xenophobia against Black sub-Saharan Africans: a State policy

Algeria is a strategic crossing point for travellers coming from sub-Saharan African countries, mostly West Africa, and these communities continue to be the target of a systematic and ferocious policy of harassment and deportation by the Algerian state. In fact, for five years, the Algerian government has been applying the same arbitrary and brutal methods towards sub-Saharan travellers: police raids and arrests, detention in holding camps and finally mass deportations to the Sahara desert where people are abandoned without any water or food. The Algerian Minister of Defence boasted that they had arrested 3,085 illegalised travellers “of different nationalities” in 2020. Falikou Dosso, a 28-year-old Ivorian recounted in January, “We were dropped off about 15 kilometers from the border. The rest we had to do on foot. That night, between 2 am and 6 am, we walked toward Niger, there were about 400 of us.” Since January, not less than 3,779 people have been pushed back from Algeria to Niger. Most of them are from West Africa, mainly from Niger, Guinea Conakry and Mali. (Source: Infomigrants.net)

The numbers are staggering, as is the violence. On 30 March, 87 buses were used to deport 5,000 people. This came hot on the heels of four mass deportations of at least 3,152 people on 5, 11, 14 and 16 March (Source: Alarm Phone Sahara). During the transfer, a tragic accident occurred where at least 50 people lost their lives on the road between Algiers and Tamanrasset (Niger). The Algerian authorities tried to cover up the accident by confiscating the survivors’ phones, but it didn’t stop the dreadful event from being publicised. One person managed to hide his phone on which he taken a video of the horror. He shared it with the press and said, “African states, NGOs and the IOM must know. African states do not have the right not to know, not to ask where their dead are.” We don’t know where the bodies of the deceased are. They might have been burried anonymously in the desert. Although this is called an “accident”, deportations are not accidental. They are part of the modus operandi of a system organized by people in postions of power. It is a system which quite deliberately leaves people who dare to exercise their right to move to die. Our hearts and thoughts are very much with the deceased and their families.

The systematic policy of repression of sub-Saharan communities goes hand in hand with racist and xenophobic narratives disseminated and, perhaps, authored by political officials. These racist tropes are deployed to justify the brutality of the means used. The Algerian government has openly adopted these policies and recognises that in doing so control Europe’s borders. This puts the government in a rather stange situation. Interestingly, The Minister of Foreign Affaires Minister recently declared in the press, “Europeans complain, but is it up to us to act as policemen for Europe?“, but he then immediately went on to stress that Algeria is doing everything it can in order “not to let these migrants leave”.

3 Shipwrecks and Missing People

In the three months this year a huge number of people have already disappeared or died while trying to reach Europe. We want to list all the incidents we have heard of here in order to memorialise them and never let them be forgotten. Nevertheless we fear that the real number of humans who have died at sea is much higher.

Muslim Cemetery on Lanzarote. Graves of deceased travellers to the Canary Islands in 2020. Source: Maria Creixell

Muslim Cemetery on Lanzarote. Graves of deceased travellers to the Canary Islands in 2020. Source: Maria Creixell

On 2 January 2021, seven bodies (three men, four women) were washed ashore off Mostaganem, Algeria. They could not be identified.

On 3 January, a body was recovered at Plage La Madrague off Oran, Algeria.

On 3 January, a body was recovered off Ouled Boughalem, Mostaganem, Algeria.

On 4 January, a body was washed ashore off Ain Témouchent, Algeria.

On 5 January, four travellers did not survive a 7-day Odyssey at sea. 47 of their fellow travellers were eventually rrescued to Tenerife.

On 6 January, the bodies of two babies were recovered among 20 survivors from a boat that had left from Nador and was intercepted by the Moroccan Marine Royale.

On 6 January, 3 people went missing as they tried to cross to peninsular Spain starting from Wad Marsa, Morocco, by boat.

On 7 January, only 21 travellers could be rescued from a boat which left from Arekmane/ Nador. The boat had set out with 31 passengers. 7 bodies were recovered from the sea. The remaining three people are still missing.

On 7 January, one person died on the journey to Gran Canaria.

On 8 January, a boat carrying 21 sub-Saharan travellers was intercepted by the Moroccan Marine Royale off Nador. Among people it carried were the dead bodies of a woman and a baby.

On 10 January, a boat with 36 sub-Saharan passengers on board went missing. The group included 5 women and a baby. It had left from Bouyafar, Nador. Alarm Phone has not been able to find a trace of them ever since.

On 10 January, a man of sub-Saharan origin was recovered dead among 88 survivors of a journey towards Tenerife.

On 10 January, a body was washed ashore at Belyounech, Morocco – the remains of a young man who presumably had tried to reach Ceuta swimming.

On 10 January, a body was washed ashore at Playa del Chorillo, Ceuta, Spain. The remains were the later identified as those of a young man, Mohammed Oulmid from Marrakech.

On 12 January, the Guardia Civil recovered a body from the sea off Ceuta.

On 13 January, out of a group of three swimmers who tried to reach Melilla via Beni Ansar only one person. The other two, nationals from Chad, remain missing. (Source: Alarm Phone)

On 16 January, a nine year-old boy of Guinean nationality, later identified as Awa D., died on his journey from Dakhla towards the Canary Islands.

On 18 January, a boat capsized off Costa de Mojacar, Spain, and 3 travellers drowned. Only 9 people survived.

On 18 January, eight young people (Jamal and Samad Talhat, Salim and Jawad Boulouad, as well as Momoun and Karim and two others) who started in a white boat inflatable boat from Nador have been missing since they last called their families. At the time of their call they were in sight of the coast of Spain.

On 20 January, one person passed away in a boat that had set off with 52 people. The boat arrived on to El Hierro, one of the Canary Islands, but another of his fellows later died in the hospital.

On 21 January, nine travellers died and three remain missing when only 14 survived the attempt to reach the Canary Islands from Dakhla, Western Sahara.

On 24 January, a body was found at Ain Brahim beach, Sidi Lakhdar, Algeria.

On 26 January, 21-year-old Moroccan national Bader al-Mutawakl drowned, trying to reach Ceuta swimming from Fnideq.

On 26 January, a body was washed ashore off Ain Témouchent, Algeria.

On 27 January, the remains of a body were recovered off Playa de la Potabilizadora, Ceuta, Spain.

On 30 January, Ayoub Fakhari y Dahani Bilal two young people from Morocco disappeared after having left for Ceuta in a kayak.

As reported on 02 February, Hussein Mubarak y Muhammad Taniber, who tried to swim to Ceuta in December 2020, are still missing. A third person survived.

On 4 February, a boat capsized off Crichtel/Oran, carrying 15 passengers. Only 8 people were rescued alive, one body was recovered, 5 people remain missing. The travellers were mainly from Tiaret, Algeria.

Since 6 February, three or four people are reported to have been missing since a boat capsized in the Bay of Algecíras. Two of them could possibly be Jawad Al-Muhammad and Hamid Al-Hassani who were reported missing on 8 February.

On 7 February, 4 Moroccan nationals went missing when a sailing boat went down off Gibraltar. Only 3 passengers survived.

On 7 February, Mohammed El-Jabari drowned while trying to reach the Spanish enclave, Ceuta, by swimming.

On 8 February, a young woman was found dead on San Amaro beach, Ceuta.

On 14 February, two Moroccan nationals drowned and 8 survivors were rescued by the Spanish Guardia Civil from a dinghy in the Alboran Sea.

In the night of 18-19 February, a boat with 17 people from Morocco and Algeria capsized off Oran, leaving only two survivors, a Moroccan and an Algerian men. Source: Alarm Phone

On 20 February, one man was recovered dead, presumably from hypothermia, from a boat that had been intercepted by the Algerian forces off Oran.

On 22 February, a mother and her son died on a boat that had left with around 60 passengers on board from Al Hoceima. The boat was eventually intercepted by the Moroccan Marine Royale.

On 23 February, bodies of two people from Algeria were washed ashore at Oran. The same day two bodies were found on the beach of Nador. They were both Moroccans from Oujda. (Source: Alarm Phone)

On 24 February, the Gibraltar Police found the body of a Moroccan man, several days after another young dead male body had been found. Presumably, the travellers belonged to a group of seven travellers whose boat had started on February 6th from Ceuta but capsized. Of the three survivors, two had been deported back to Morocco. Several are still missing.

On 2 March, the body of a 20-year old sub-Saharan national was recovered at Playa de los Cárabos, Melilla.

On 2 March, a body was recovered floating off Horcas Coloradas beach in Melilla, Spain.

On 2 March, the health service was alerted to two people in the area of Dique Sur, Melilla. One of them showed severe symptoms of hypothermia. The other person was unconscious but could not be resuscitated.

On 8 March, 5 people died during a journey towards Gran Canaria. 47 travellers were rescued about 250km off the Spanish island. One body was recovered. Four people went missing at sea.

On 8 March, a body of a young Moroccan national was washed ashore off Algeciras, Spain.

On 8 March, the remains of a body were found off Playa de los Carabos, Melilla.

On 13 March, the body of a Moroccan national, who would have turned 18 in April, was recovered at Calamocarro in Ceuta. Apparently, he and a friend were trying to swim to the Peninsula starting from the ship, El Tarajal. He was buried two days later in Ceuta.

On 17 March, 36 travellers were rescued from a boat towards Gran Canaria. One person did not survive the journey. His body was recovered from the boat.

On 21 March, a two-year old girl eventually died in a hospital in Gran Canaria after having survived a 5-day journey from Dakhla towards the Canary island. She had been travelling with 52 other people.

On 25 March, the Alarm Phone was alerted to a boat carrying 50 people (including ten women and four children) that started from Laayoune, Western Sahara, heading for the Canary Islands. Salvamento Marítimo was looking for the boat for days, but there is still no trace of the travellers.

On 26 March, a boat capsized off Tenerife. Three people died. 42 people were rescued.

On 27 March, two people drowned and 9 remain missing when a boat from Algeria capsized off Murcia, leaving only 3 survivors.

4 CommemorActions – 6 February

Despite all these deaths at sea and the continuous reinforcement of the outer borders of Europe, people on the move keep on fighting for their freedom of movement and expanding their networks of solidarity. This became very visible in this year’s CommemorActions.

Like last year, 6 February 2021 gave rise to many “CommemorActions” in several cities of Morocco, in Senegal and elsewhere. The date of 6 February was chosen by activists from the Alarm Phone network in 2020 as an “International day of CommemorAction for people killed and missing on the migration routes”. A day to remember, to honor those who have disappeared, and to show that we do not forget, and that we will relentlessly continue to hold to account those responsible for this deadly border regime.

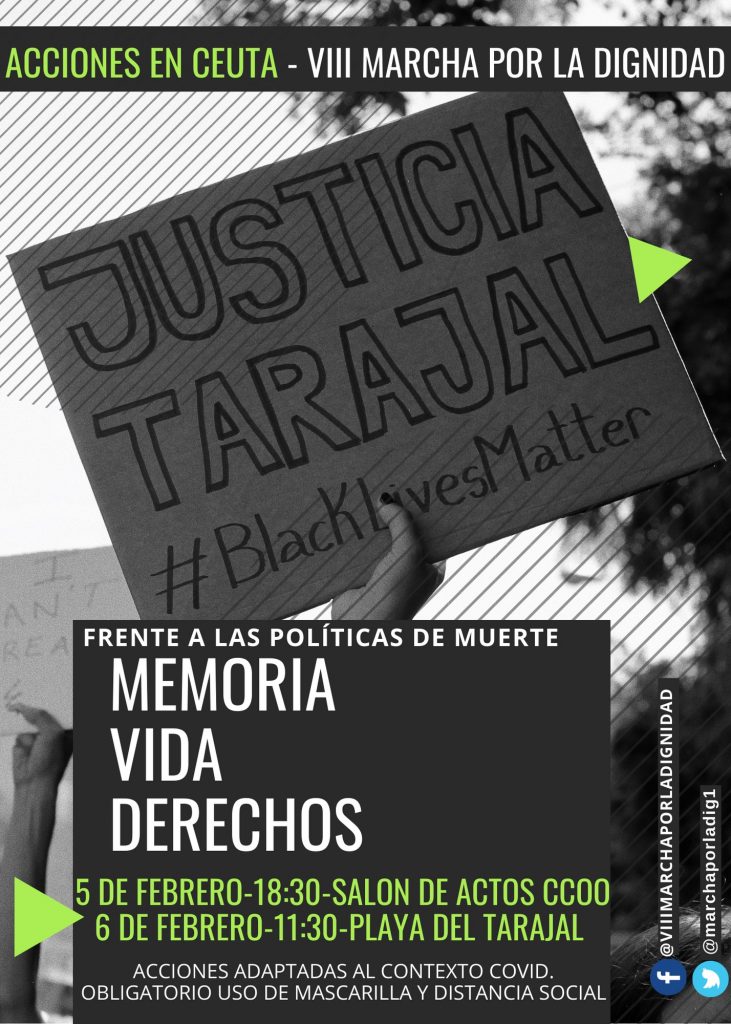

On 6 February 2014, more than 200 people tried to enter the city of Ceuta, a Spanish enclave, from Moroccan territory through the beach of Tarajal. The Spanish Guardia Civil fired smoke cartridges and rubber bullets at the people in the water in an attempt to prevent them from entering Spanish territory. Fifteen people were killed on the Spanish side, dozens disappeared and others died in Moroccan territory. The legal battle to prosecute those responsible for this massacre continues in Spain to this day.

Despite the difficult and exceptional conditions imposed by the Covid-19 pandemic, on Saturday, 6 February 2021, Transnational CommemorActions for those who died on the move took place in, among other places, Agadez in Niger; Sokodé in Togo; Laayoune in Western Sahara; Tangiers, Oujda and Saidia in Morocco; Dakar and Gandiol in Senegal; Madrid and other cities in Spain, Brussels and Liège in Belgium and Berlin and Frankfurt in Germany. Additionally, Alarm Phone published a video showing the commemorActions from last year.

Excerpts of the statement by Alarm Phone Oujda for the CommemorAction in Oujda and Saidia on 6 February 2021:

“On 6th of February 2021, we will come together to turn our grief into collective action. We come from diverse backgrounds. We are relatives of the disappeared from Tunisia, Algeria, Morocco, Cameroon, Senegal, Syria, Mexico, Peru and elsewhere. We are those who find human remains in the desert and the sea, who try to identify the dead in the different border areas, who give the nameless bodies a dignified burial. We are the ones who hold hands when we miss a daughter, a son, a sister, a brother, a friend.

[…]

With our term ‘CommemorAction’ we offer a promise: we will not forget those who have lost their lives or gone missing and we will fight against murderous border regimes. We will offer a space for commemoration and collectively build something out of our grief. We will not be alone and we will not give up. We will continue to fight for freedom of movement and human dignity for all in our daily lives.”

Most of the following events, reports and pictures, as well as the full statement, can be viewed on the Alarm Phone Sahara website: 6th of February 2021: International day of CommemorAction for people killed and missing on the migration routes.

OUJDA & SAIDIA / Morocco

The Alarm Phone, in collaboration with local initiatives, organised a Caravan in Oujda with an exhibition and a presentation on migration by students. A commemorative ceremony was organised in the coastal town of Saidia. There was also a meeting with families and friends of the disappeared:

6 February 2021 in Oujda: Meeting with families, friends of the disappeared. Source: Alarm Phone Oujda

6 February 2021 in Oujda: Meeting with families, friends of the disappeared. Source: Alarm Phone Oujda

TANGIER / Morocco

Members of the AP Tangier team reported that the day of CommemorAction on 6 February aims to make the voice of the voiceless heard as they mourn their dead, and reminds migrants that “This is our day, we can express what is in our hearts without shame, without embarrassment“. In Tangier the day was a success: some sympathisers gathered to lay flowers at the beach (the Sahariano collective), and later a time of awareness-raising and distribution of AP cards and Welcome2Spain guides took place. A soccer game was organised, followed by a discussion during which we detailed the vision of Alarm Phone. A moment of silence and prayers allowed us to think about how many people die every day in the seas and at the borders.

6 Febrary 2021 in Tangier: Women standing behind the banner “Naufrages et décès en Méditerranée occidentale et sur la route atlantique en 2020” (“Shipwrecks and deaths in the Western Mediterranean and on the Atlantic route in 2020”). Source: Alarm Phone

6 Febrary 2021 in Tangier: Women standing behind the banner “Naufrages et décès en Méditerranée occidentale et sur la route atlantique en 2020” (“Shipwrecks and deaths in the Western Mediterranean and on the Atlantic route in 2020”). Source: Alarm Phone

6 February 2021 in Tangier: The laying of flowers at Tanger ville beach. Source: Alarm Phone

6 February 2021 in Tangier: The laying of flowers at Tanger ville beach. Source: Alarm Phone

LAAYOUNE / Western Sahara

Report from Laayoune, by local AP activist:

“Despite the pandemic, we were able to meet to highlight the days of 6 and 7 February. On 6 February, we received families of victims, set up interactions, with the participation of the association Sakia el Hamra and the activist collective SAMPO of Rabat. It was a day full of rich debates and with an exhibition about the areas of the South where we could see the rocks of Tarfaya which sometimes hide the bodies that are never found. And we were able to finish the commemoration on 7 February with the Senegalese community with prayers and performances of Khassaid poems.”

6 February 2021 in Laayoune: activists posing with a banner “Arrêtez la mort en mer” (“Stop death at sea”). Source: Alarm Phone

6 February 2021 in Laayoune: activists posing with a banner “Arrêtez la mort en mer” (“Stop death at sea”). Source: Alarm Phone

DAKAR / Senegal

The Boza Fii initiative organised a sit-in, showing a banner with the names of the dead and missing. They declared:

“These missing people have given us a lesson in life and we would like to say that to forget them is to kill them a second time. In memory of those who did not arrive. It was not an accident, it was not a tragedy. It was 145 rubber bullets fired by the Spanish police at migrants who were in the water. It was a political assassination, the murder of 15 companions who were disobeying the institutional racism regime. Justice and reparation. #TARAJAL! “

Poster announcing the event of 6 February 2021 in Dakar. Source: Alarm Phone Sahara

Poster announcing the event of 6 February 2021 in Dakar. Source: Alarm Phone Sahara

Report by Babacar Ndiaye, Alarm Phone activist:

“The commemoration of 6 February, organised here in Senegal for the first time with members of Alarm Phone Senegal, was warmly welcomed by the population here because there are some people who do not know what happens to the people who cross the Mediterranean or the Atlantic Ocean or the desert. They also don’t know that there are networks that closely track the movements of migrants. So that’s why we made this event, very limited because of the pandemic, but it was a success. […] ‘La main sur le coeur.’ ” (‘Hand on heart’).

6 February 2021 in Dakar. Source: Alarm Phone

6 February 2021 in Dakar. Source: Alarm Phone

GANDIOL / Senegal

There was a CommemorAction organised in the Aminata Cultura Centre in Gandiol. There were screenings, discussions, the reading of the manifesto, a minute of silence and a musical performance.

6 February 2021 in Gandiol: Musical performance at the Aminata Cultura Centre. Source: Facebook Page Centre Culturel Aminata de Gandiol

6 February 2021 in Gandiol: Musical performance at the Aminata Cultura Centre. Source: Facebook Page Centre Culturel Aminata de Gandiol

AGADEZ / Niger

Like last year, there was a very rich event organised in Agadez, with a reading of the declaration on the externalisation of borders and their consequences for freedom of movement, a screening of videos of travellers testimonies (in French and English), and a debate between participants on the daily experience of people on the move. Furthermore, there were speeches by family members who have lost their loved ones, words of migrants who witnessed atrocities during their travels and the projection of images of an unidentified person’s grave in the desert which was used as an image to prompt reflection. In a statement the coordinators of Alarm Phone Sahara asked those present to join them in a moment of silence: “At this solemn moment, I ask those present to observe a minute of silence in memory of these victims of the cynical policies of externalisation of borders.” (watch full statement in French here)

SOKODÉ / Togo

In Sokodé the members of the Togolese Association of Deportees (ATE) met with families to discuss, educate each other, and commemorate those who lost their lives. Together they put flowers in the river Na to think of those who died or went missing because of the irregularization of migration. In a radio program causes and solutions to the problem of irregular migration were discussed.

6 February 2021 in Sokodé: Participants posing in front of a CommemorAction banner “Journée de commémoration des morts et disparus aux frontières dans la mer et dans le désert” (“Day for the Dead and Missing at the Borders in the Sea and in the Desert”). Source: Alarm Phone Sahara