The analysis is also available as a PDF.

| ‘Mother’

I do not like death as you think, I just have no desire for life… I am tired of the situation I am in now.. If I did not move then I will die a slow death worse than the deaths in the Mediterranean. ‘Mother’ The water is so salty that I am tasting it, mom, I am about to drown. My mother, the water is very hot and she started to eat my skin… Please mom, I did not choose this path myself… the circumstances forced me to go. This adventure, which will strip my soul, after a while… I did not find myself nor the one who called it a home that dwells in me. ‘Mother’ There are bodies around me, and others hasten to die like me, although we know whatever we do we will die.. my mother, there are rescue ships! They laugh and enjoy our death and only photograph us when we are drowning and save a fraction of us… Mom, I am among those who will let him savor the torment and then die. Whatever bushes and valleys of my country, my neighbours’ daughters and my cousins, my friends with whom I play football and sing with them in the corners of homes, I am about to leave everything related to you. Send peace to my sweetheart and tell her that she has no objection to marrying someone other than me… If I ask you, my sweetheart, tell her that this person whom we are talking about, he has rested.. He is resting from the rows of bread and not having the right to coffee.. he used to buy you gifts after taking a debt from his friends.. Farewell, you who heard my message (I drowned). |

A letter by

|

Introduction

Over the past six months, from July to December 2020, we witnessed a continuity in the Central Mediterranean Sea, with Italian and Maltese state actors withdrawing from their rescue obligations, the administrative detention of the civil fleet and the unresponsiveness of the so-called Libyan Coast Guard in situations where people were in extreme distress off the Libyan shores. The combination of these elements has inevitably led to an increasing rescue gap, more suffering and many shipwrecks at sea.

Despite the attempts to let people die at sea, the rescue gap left by the absence of rescue did not stop people from fleeing the dire living conditions and arbitrary detention to which they are routinely subjected to in Libya, as well as those escaping the worsening economic crisis in Tunisia. Many people indeed have attempted this dangerous journey and arrived autonomously to Italy and Malta. On the 1st and 2nd November alone, a total of 13 boats arrived to Lampedusa. Moreover, our network has observed an increase in reports of boats having left from Algeria, heading for Sardinia. We continue to be amazed by the ongoing struggle for freedom of movement and dignity of migrants themselves. These autonomous arrivals are the sign that the EU border regime, despite its death drive, will never be able to fully contain the life force of people seeking to better their lives and escape oppression.

We estimate that overall, 27,435 people tried to leave Libya in 2020. 11,891 of them were intercepted by the so-called Libyan Coast Guards and pushed back to Libya according to the IOM. The IOM considers that 848 people died on the central Mediterranean route but this is certainly an underestimation. About 5,375 people in 75 boats arrived to Lampedusa from Libya – autonomously or with the help of the Italian Coast Guards. Almost 3,700 people were rescued by NGO-vessels to Italy, 2,281 people arrived in Malta. In 2020 still, 26,349 people tried to leave Tunisia. Amongst them 12.883 people reached Italy, but 13.466 people were intercepted by the Tunisian Coast Guard, according to the FTDES.

Over the past year, the Alarm Phone supported 172 boats in distress in the Central Mediterranean carrying around 10,074 people. Mostly, these boats left from Libya but some also from Tunisia and Algeria. Of the people who reached out to us, about 7,503 were rescued to Europe by NGO vessels, arrived on their own or were rescued by Maltese and Italian assets. 211 were rescued by merchant vessels. Approximately 2,390 people on 42 boats who alerted Alarm Phone in 2020 were intercepted by the so-called Libyan Coast Guards. Of those who called Alarm Phone, 219 people unfortunately drowned or went missing. We also collected several testimonies about many more confirmed shipwrecks of boats that did not alert us when in distress. Lastly, the fate of about 578 people who called us, is unknown to us.

Given the few governmental and nongovernmental assets left at sea to conduct rescues, the important role merchant vessels have come to play in the Central Mediterranean has become more visible in these past months. Over the Summer and Autumn, the Alarm Phone repeatedly called on merchant vessels to intervene, and to meet their obligations to preserve life under the international law of the sea. August saw the longest stand-off in the history of the Central Mediterranean: MV Etienne took onboard 27 migrants on August 5 who were finally transferred to the Italian NGO ship Mare Jonio on September 11 after 38 days on board. The italian company Augusta offshore has also intervened several times over the past months to rescue boats in distress and disembarked the survivors in Italy. In the analysis below we outline how the company’s behaviour could be influenced by judicial developments in Italy.

The civil fleet has once more faced administrative intimidation from EU member states, with Italian authorities in particular using Port State Control as a way to keep NGO ships from going out to sea for months. As a result, the Alarm Phone has often been the only operational actor left to monitor human rights violations at sea. Over the past months, we had to struggle for every boat in distress that reached out to us and we were often successful in putting pressure on authorities to act. Our continued fight for and with the people attempting the dangerous central Mediterranean crossing has also meant that we have gained credibility and trust among migrant communities themselves. Calls from relatives and friends searching for their disappeared loved ones have therefore increased.

As a consequence, the Alarm Phone has documented hundreds of invisibilized deaths through the testimonies and calls of relatives and survivors of shipwrecks, as well as from local fishermen. We never received so many accounts of invisibilized shipwrecks as over the past 6 months. Due to the black hole that the Central Mediterranea sea has become, it is difficult for us to tell if this is an indication of more shipwrecks happening in the last months, or simply a result of more relatives and survivors reaching out to us to report these tragedies. In this 6-month report, we try to account for some of these tragedies. Still, we fear that many deaths remained unreported, with boats disappearing at sea and families and friends being left to search in the dark for months. Many times, we are powerless when faced with their questions and we ourselves also often feel compelled to ask the European authorities in charge of upholding this senseless border regime: Where are they and what have you done to find them? Why do their lives not matter?

This analysis is organised into seven sections:

CHRONOLOGY – July to December 2020

July

In July about 180 people who alerted Alarm Phone were rescued by merchant vessels and brought to Europe. 451 people were rescued by the Italian Coast Guard, 186 by Malta. 227 people reached Lampedusa on their own. 459 people were pushed back to Libya. In total, Alarm Phone was busy with 23 cases in the Central Med during July. We do not know about missing or dead people.

The second half of the year began with the much needed presence of two NGO vessels in the Central Med. On 1st July, Ocean Viking rescued 16 people on a fibreglass boat in distress 40nm south of Lampedusa. The NGO vessel had 180 survivors on onboard, but after its arrival in Porto Empedocle more than 2 weeks later, it was subject to “administrative detention”. The same had already happened to the Sea Watch 3 back on 8th July. From this moment on, no NGO vessel was present in the Central Med and authorities often refused to rescue people in distress. Luckily some boats that called the Alarm Phone reached Lampedusa on their own – for a total of 227 people in July.

In absence of governmental and non-governmental rescue, in several cases merchant vessels attended to migrants in distress at sea. On 4th July, the merchant vessel Talia rescued 52 people, who had reached out to Alarm Phone. The crew showed much solidarity with the rescued, but Maltese authorities refused to transship the migrants or to assign Talia a port of disembarkation. Only on 7th July, after days in inhumane conditions on this livestock carrier off Malta’s coast, the people were finally allowed to touch land in Europe. Another merchant vessel, the Italian flagged Cosmo, rescued 110 people in distress who called us in panic on 24th July. Finally, Malta took responsibility for the operation, and coordinated the rescue by the merchant vessel over the radio. The rescued were later disembarked in Pozzallo, Sicily.

In several cases, Malta only reacted after a lot of pressure by civil society organisations and did not provide any information on rescue operations. 65 people who called us on 16th July were rescued after one day of distress. We, and desperately worried relatives who were calling us from all over Europe, had to learn about their rescue through the media, as RCC Malta refused to give out any information.

Italy also regularly delayed rescues. A boat with 60 migrants that reached out to Alarm Phone on 13th July was rescued to Lampedusa after having been abandoned adrift for 40 hours. Aerial pictures taken by a Moonbird revealed an Italian coastguard vessel and a commercial cargo ship apparently ignoring the boat in distress only a mile away from their position. On 26th July, the Italian Coast Guard rescued several boats in Maltese SAR zone and, at the end of the month, they even sent the Italian flagged vessel Asso 29 to a boat in Libyan SAR zone (more about this case in the chapter below).

Often, the so-called Libyan Coast Guard did not react or reacted only very late, as on 22nd July, when 131 people in distress were abandoned adrift for several hours, despite continuous alerts by Alarm Phone and by Moonbird, and were eventually returned to Libya. However, they seemed very quick in pushing back boats which were still proceeding, often using violence and killing the people they are allegedly rescuing. On 29th July, after intercepting a group of migrants at sea, Libyan authorities opened fire on them, killing 2 Sudanese migrants and injuring several others.

On 31st July, Tunisian Coast Guard rescued about 70 migrants on a boat that had reached out to us.

August

In August, Alarm Phone was alerted to 24 distress cases in the Central Med. Of these, 200 people were rescued by NGOs, 189 by Italian authorities, 71 by Maltese authorities, 27 by merchant vessels and as many as 573 people arrived to Italy by themselves. Altogether, 1033 people reached Europe. 115 were pushed back to Libya. Sadly, about 80 people were reported missing or dead.

August was a busy month for Alarm Phone, for the Etienne merchant vessel and, towards the end of the month, for some NGO vessels that were able to conduct rescue missions at sea.

On 1st August, four boats alerted Alarm Phone. Three of these boats reached Lampedusa. The fourth boat was eventually rescued by the Armed Forces of Malta after the non-assistance by a merchant vessel nearby. Some days later, on 5th August, the merchant vessel Etienne of Maersk Tankers rescued 27 people in distress but was punished with the longest ever stand-off outside European territorial waters. After pressure by the media, by the UNHCR and by many other organisations, Malta still refused disembarkment. On 11th September, after 38 days on board, the 27 rescued people were eventually transferred to the Italian NGO ship Mare Jonio.

In mid August several boats both from Libya and from Tunisia reached Lampedusa. Unfortunately, several people died at sea as a result of attacks and shipwrecks happened as well. Between 16th and 17th August a boat was attacked at sea by an unidentified group off Zuwara, the people were shot at, the engine exploded and their boat caught fire, causing the death of at least 45 people. Some 37 survivors were rescued by local fishermen and some were detained upon disembarkation. Just a day later another shipwreck happened in the same area, tragically. The people on board the white rubber boat called Alarm Phone on the morning of 18th August. Whilst we were on the phone, a tube burst. Of the 95 people on board, only 65 of them survived, thanks to the efforts of local fishermen. Alarm Phone was also alerted to two other shipwrecks that took place that week, by relatives of the victims and by the few survivors. Alarm Phone published a detailed report containing testimonies and reconstructions of these four shipwrecks.

Towards the end of August, Sea Watch 4 was able to come back to the Central Med and conducted three rescue operations, bringing to safety more than 200 people in less than 48 hours. The Louise Michel, a new civil rescue vessel, arrived in the Central Med on 27th August. Only one day later, they almost had to declare ‘state of emergency’ after rescuing over 200 people off Libya’s coast, while the European authorities ignored their request for help. Luckily, the Sea Watch 4 offered support and took some people on board. 49 vulnerable people and a dead body were later transshipped from the Louise Michel to a Coast Guard vessel and were disembarked in Lampedusa on 29th August.

A migrant boat burst into flames off the southern Italian coast on 30th August. The vessel suddenly caught fire, as Italian navy ship was in the process of taking people onboard. The same day, a boat with 450 migrants onboard was rescued by the Italian coastguard off the island of Lampedusa. During 24 hours, a further 500 migrants arrived at Lampedusa on small boats.

September

Alarm Phone was involved in 15 cases in September. 425 people on these boats were pushed back to Libya. 3 people were missing or dead. 429 reached Europe, 159 by themselves. 177 were rescued by NGOs, 93 by Italy, none by Malta.

At the beginning of September, several NGO vessels were on mission in the Central Med. But their presence did not last long. On 2nd September, Sea Watch 4 disembarked in Palermo the 353 survivors they had on board, and hoped to return to Europe’s deadliest sea border as soon as possible. But the vessel was put under a 14 days quarantine in the port of Palermo and denied crew change.

At the beginning of September, Open Arms could return to the Central Med, and on 8th September they rescued ~83 people who had called Alarm Phone when in distress at sea.

Three days later Open Arms rescued two other boats with 65 and 77 people that had alerted Alarm Phone. The people, however, were not allowed to disembark. On 17th September, about 76 people who were on board of Open Arms jumped into the water in an attempt to reach the shore.

In mid September, Sea Eye‘s Alan Kurdi could rescue several boats in distress, with a total of 144 survivors. On 24th September they were allowed to disembark all the rescued in Sardinia, but the vessel has been blocked there ever since. The next day, the rescue vessel Mare Jonio was also blocked by Italian authorities, allegedly for administrative reasons.

Administrative measures were not only used to block NGO rescue vessels, but also to ground SAR airplanes. Moonbird, by Sea Watch, was grounded by Italian authorities on 8th September. Alarm Phone protested. At least Seabird could fly in the second half of September and discover boats in distress.

On 8th September, Alarm Phone was alerted to a boat with about 25 people in distress in the Ionian Sea, an unusual area for distress calls towards Alarm Phone. In mid September, the so-called Libyan coast guard intercepted three boats that had called Alarm Phone and, unfortunately, one of these boats had capsized, with at least 24 people feared drowned. The other two boats were forced back to Libya. Another shipwreck happened on 19th September off Garabulli. A fisherman called Alarm Phone at night, telling us that he had rescued 21 people from a deflating rubber dinghy, but he had to leave 33 people behind, clinging on the rubber boat tubes. He told us that he had tried to inform authorities but there was no reaction. He then alerted his network of fisherman, in the hope that some else had the capacity to rescue the 33 people left behind. The day after, we were informed that indeed another fishermen rescued the remaining shipwrecked, but that at least 3 people were missing and feared dead.

Between 14th and 25th September, survivors and relatives of the missing reported to Alarm Phone at least 6 shipwrecks off the Libyan coast, and according to the reconstructions the few survivors were taken ashore by fishing vessels. On 27th September, Alarm Phone published a report to reconstruct these tragic shipwrecks where at least 200 lives were taken by the violent border regime.

October

In October, the Alarm Phone was alerted to 10 boats in distress in the Central Med. Four people of these boats were rescued by a merchant vessel, 6 by the Italian Coast Guard, 159 by Malta and 370 reached Lampedusa by themselves. In total 535 of the people who called us arrived in Europe. There was no NGO vessel in the SAR area. We learnt about 5 deaths and one push back to Libya.

In October, no NGO boat was allowed to be at sea, due to so-called administrative detention by Italian authorities. In this context, many preventable shipwrecks happened, but there were also some autonomous arrivals.

The month began with 84 people arriving autonomously in Lampedusa, on 2nd October. On the same night, about 38 people on a boat in distress reached out to Alarm Phone. They were drifting in the Maltese SAR zone. The merchant vessel Ambra was monitoring the boat, and the shipping company of Ambra informed us that Armed Forces of Malta were at the scene, had failed to fix the boat’s engine, and were then towing the boat. Although RCC Malta failed to confirm the rescue, we believe that the boat has been rescued and brought to Malta. Many of their relatives had contacted Alarm Phone as they were worried.

On 5th October, we were alerted by a boat with 5 people in distress in Maltese SAR zone. One of them needed urgent medical care. Malta did not pick up the phone and, as usual, Italy declared they were not responsible for boats in that area. Eventually we learned that four out of the 5 people in distress were rescued to Lampedusa by merchant vessel Asso 29, whereas the man with the serious health issues was evacuated by helicopter and taken back to Libya.

On 11th October 2020, the Alarm Phone turned six years old. On the same evening we were reminded of how important and difficult is our work: we were alerted by people in distress in international waters, close to Malta SAR zone, whilst a strong storm was approaching. Only after days of non-assistance, on 14th October, the ~43 people were rescued and finally disembarked in Malta. How they survived the storm, whilst drifting at sea for so many days, we will never know. What we do know, is that without public pressure to rescue them, they might have disappeared or been brought back to a Libyan prison.

The next day we learned that a terrible shipwreck had occurred off Sfax/Tunisia. Unfortunately only 7 people survived, whilst 11 bodies were found and 11 more people were missing, feared dead. According to news reports, the boat caught fire and people jumped into the sea. The Tunisian Coastguard tried to rescue the shipwrecked but they seemed to have come too late for at least 22 people.

In the second half of the month, several other shipwrecks were reported to Alarm Phone. One happened off the coast of Sabratha, Libya on 21st October and claimed at least 15 lives, including Abul Latif Habib Doria, whose letter introduces this report. Five survivors were brought to shore by fishermen. One day later a shipwreck off Lampedusa was reported and five people were feared dead, including two girls and a pregnant woman. Also in this case, the 15 survivors were rescued by fishermen. On 30th of October, a boat with 14 survivors on board, which departed from Benghazi, was found by Libyan authorities, after they had been drifting at sea for 15 days.

At the end of October, heavy winds from north did not only prevent boats from leaving, but also led to the temporary suspension of Tripoli Port’s marine traffic due to bad weather.

In October, we also received calls from boats that departed from Algeria, and heading towards Sardinia. A boat with 11 people on board departed from Annaba, Algeria, on 9th October, and disappeared. Worried relatives called Alarm Phone several times. After several days with the Italian coastguard searching off the Sardinian coast, worried relatives calling Alarm Phone and authorities, and public pressure on authorities to continue their search activities, on 19th October the boat was finally localized very far away from its expected position, off the Sicilian coast, near Mazara del Vallo. Unfortunately, over the 10 days of distress at sea five people had died and only six people were found alive. On the same day Alarm Phone was contacted by relatives concerned for a missing boat that had also left Algeria to reach Sardinia. They later reported to us that the boat had been intercepted by the Algerian Coastguard.

November

In November, especially during the first two weeks, Alarm Phone was involved in 23 cases. 280 people on boats we were alerted of, were rescued by the NGO rescue vessel Open Arms; 70 people were rescued by the Italian Coast Guard; 20 people were rescued by the Armed Forces of Malta and 927 (!) people reached Lampedusa by themselves. Altogether 1,297 people who alerted the Alarm Phone arrived in Europe. 291 were pushed back to Libya and, unfortunately, at least 132 people died or went missing in several visible and invisible shipwrecks .

The month began with many autonomous arrivals in Lampedusa: 13 boats within just 24 hours, between 1st and 2nd November. On 3rd November, Alarm Phone was alerted by 5 boats in distress in the Maltese SAR zone, close to Lampedusa. Some other boats called us in the following days, but it was very difficult or impossible, to find out what happened to the people who called us, due to the usual lack of transparency by the Italian authorities and the confusion created by so many arrivals on the island, making it almost impossible to identify particular boats. On 7th November, a particularly big boat with 160 people on board, mostly from Bangladesh, arrived in Lampedusa.

The same day, we were alerted by an overcrowded rubber boat with ~100 people in distress off AlKhums. The day after we were informed that, after three terrible days at sea, the migrants were forcibly captured back to Libya. Many other boats were intercepted and forced back to Libya during these days, for a total of 270 people.

Between 1st and 15th November, 23 boats with ~1700 people escaping Libya called Alarm Phone. 13 of these boats (~1,100 people) reached Italy, but five boats were captured by the so-called Libyan Coast Guard, and one boat reached Malta.

Three of these 13 boats were rescued by Open Arms, which reached the so-called Libyan SAR zone on 10th November. The 3 boats had about 250 people on board, but unfortunately, not all of them survived: 6 people died during the rescue operation, as the boat capsized and everyone fell into the water. This boat had also been spotted by Frontex during one of their surveillance flights. On the same day, Open Arms had also searched for another boat with 19 people on board, but they could not find it. We requested an aerial search for this second boat, but in vain. Nobody searched further, the boat capsized and up to 19 people drowned, amidst media silence and public invisibility and continuous lack of accountability.

In November alone, 132 deaths were reported to Alarm Phone along the Central Mediterranean route: a massacre at Europe‘s doorstep, which could have been avoided if authorities had responded adequately to distress calls. Alarm Phone collected testimonies from survivors and relatives of the people who went missing in these shipwrecks, and we published a report reconstructing the events. Since then, two more shipwrecks have been reported to Alarm Phone: on 19 November, relatives informed us that a boat with 56 people had departed from Garabulli, and that they had lost contact with their loved ones. We immediately alerted all authorities, but nothing has been done to find them and the people have been missing since. Another small boat with 11 people was reported missing since 9th November: according to relatives, one person had survived after swimming ashore to find help for his fellow travellers. Unfortunately it was too late when authorities arrived, and only the floating remains of the boat could be found. We are still investigating a third potential shipwreck, as a boat with 15 people seems to be missing since 14 November: it is unclear, however, whether the people might have arrived in Lampedusa but were imprisoned on the quarantine ships and unable to communicate with their worried relatives, who are still desperately searching for them.

Concerning the court case of the „El Hiblu 3“ in Malta, in November Amnesty International has launched a campaign for the three young men facing life in prison for resisting the forced return of their fellow travellers and themselves to the place they had risked their lives to escape from: Libya.

December

In December, Alarm Phone was involved only in 5 distress cases in the Central Med. Of these cases, none were rescued by Italian or Maltese Coastguards: 65 people reached Lampedusa on their own, 95 people were pushed back to Libya. 13 people are still missing and feared dead. Open Arms rescued 169 people who had alerted us.

In December, bad weather prevented boats from leaving Libya. On 1st December, two boats that had departed from Tunisia called Alarm Phone: the first arrived in Lampedusa, and the second was intercepted back to Tunisia. In the second week of December, several boats arrived autonomously in Lampedusa from Tunisia and Libya, for a total of about 300 people. On 23rd December, a boat that had departed from Libya called us and we believe it arrived in Lampedusa, together with two other boats, between the 23rd and 24th December. On 5th and 23rd December, there were boats arriving in Crotone from Turkey.

In December there were also many interceptions by the so-called Libyan Coast Guard and shipwrecks were reported. On 16th December, the bodies of four children were found on the west coast of Libya, and two adult bodies were found the following days. There were unconfirmed reports of a boat sinking, with approximately 30 people onboard, but it is still unclear whether or not the bodies were related to a potential shipwreck.

On 24th December a horrible shipwreck off Tunisia occurred, just 4 nautical miles off Sfax: 20 people were confirmed dead and 20 people are reported missing – only 5 people seem to have survived. On Christmas Day, Alarm Phone was alerted by relatives of people who escaped Libya on a small boat with 13 people on board. We could never establish contact with the boat, but we believe that Pilote Volontaires spotted the same boat and reported its exact position to the authorities. Unfortunately, the boat was not searched for, there were no reports of arrivals or interceptions, and the people are still missing, at this point feared dead.

After these terrible months, the year ended with some good news: on 21st December, the Ocean Viking was released after 5 months of administrative detention, and it was announced that the (il)legality of the detention of the Sea Watch ships will be reviewed by the European Court of Justice. Open Arms came back to the Libyan SAR zone on 25th December. On the last night of the year they rescued 169 people from a boat in distress that had alerted Alarm Phone, and on the second day of 2021 they rescued another boat that had alerted Alarm Phone, with 96 people on board. In just two days they rescued 265 people, which gives us hope and strength for continuing our struggle in support of people on the move in 2021.

Civil fleet in “administrative detention” – Merchant Vessels rescue

People safe on the Louise Michel. Foto: Louise Michel

People safe on the Louise Michel. Foto: Louise Michel

In the second half of 2020, authorities tried by all means to prevent the NGO vessels from leaving harbors for search and rescue missions. As a consequence, for most of the time Alarm Phone was the only actor active in the Central Mediterranean sea.

Sea Watch 3 was the first NGO vessel subjected to ‘administrative detention“ on 8th July in Palermo, officially because of “several irregularities of a technical and operational nature“ according to Coast Guard inspectors. The ship is now under maintenance in Spain.

Ocean Viking was the next ship to be blocked – on 22nd July – after its arrival in Porto Empedocle with 180 survivors on board. The main reason, as notified by the Italian Coast Guard, was that “the ship has been carrying more persons than the number certified according to the Cargo Ship Safety Equipment Certificate”. However, the ship status had remained unchanged throughout four previous inspections, and there had been no changes in the relevant safety regulations with regards to what was later being challenged. After 5 months of administrative detention, Ocean Viking was released on 21st December.

Sea Watch 4 came back at sea at the end of August and – after three rescue operations – it was detained in Palermo. Their return to the SAR zone is unforeseeable.

Alan Kurdi could disembark 144 rescued people in Sardinia on 24th September, but since then the vessel has been blocked there. During an inspection, the Italian authorities allegedly found technical deficiencies. Among other things, the sewage tanks were too small, they said. A letter exchange published in The Spiegel proved that the German Minister of Interior, Horst Seehofer, had actually tried to convince the Minister of Transport, Scheuer, to harass German sea rescuers: “in my opinion, there is a considerable discrepancy between the requirements for the equipment of cargo ships, which are applied to the ship in the present case, and the actual requirements, which lie in the ship’s self-declared mission”, he argued. The Ministry of Transport responded to Seehofer that the ship had the necessary certificates, and contended that “according to international law, sea rescue has priority over safety and environmental requirements in case of doubt.“ In addition, Scheuer wrote that even the ships of the German Armed Forces, which sometimes rescue refugees in the Mediterranean, do not have additional waste water tanks.

Louise Michel, a new civil rescue vessel, funded by British street artist Banksy, arrived in the Central Med on 27th August, rescued over 200 people and almost had to declare state of emergency – due to the boat’s instability with so many people on board – but authorities refused to intervene in support for the crew and the people they rescued. The ship is not expected to come back at sea before March 2021.

Mare Jonio – by Mediterranea – was also blocked from leaving the port of Venice on 29th September. The court of Agrigento acquitted Mediterranea from all charges they were facing after their very first rescue operation on 18th March 2019, but four criminal investigations are still open.

Aita Mari was blocked in Palermo for 49 days, and was finally allowed to return to Spain, but only to carry out the repairs and improvements that were required by its technical inspection. They are now planning a mission at the end of January, but a new stability test is demanded within 12 months.

Open Arms was the only NGO vessel which could come back to the Libyan SAR zone several times this year: at the beginning of September, on 10th November and on 25th December.

Not only rescue vessels were blocked for months or are still blocked. Authorities also tried to prevent air monitoring. Moonbird of Sea Watch was grounded by Italian authorities on 8th September. The reason given was that Moonbird had spent too many hours over the Mediterranean sea assisting people in distress and documenting human rights violations. Allegedly, their aerial reconnaissance mission would hinder ongoing sea rescues by the Italian authorities. At the end of November Moonbird could come back at sea. At the end of December, Pilotes Volontaires were surveilling the Central Med on their airplane Colibri.

Court cases about blocked NGO vessels

In 2019, Open Arms accused Salvini of blocking their ship in a long standoff and kidnapping the migrants they had on board. At the end of July 2020, Italy’s Senate voted to allow a trial against the former Minister of Interior, who will be prosecuted for not allowing the Open Arms vessel to disembark rescued migrants on the Italian territory.

For the first time, the European Court of Justice is also getting involved in NGO-led SAR operations. On 23rd December, the Palermo’s administrative court decided to refer the case of Sea Watch blocked ships to the European Court of Justice. The court will (hopefully) decide whether Italy violates European Law when detaining NGO vessels.

Migrants next to the merchant vessel MAERSK Etienne before rescue. Foto: Sea-Watch.org

Migrants next to the merchant vessel MAERSK Etienne before rescue. Foto: Sea-Watch.org

Over the past six months, due to the absence of both governmental and non-governmental rescue assets, often the only actors capable of rescuing people in distress were merchant vessels. In at least three cases, Alarm Phone alerted merchant vessels to boats in distress. After the merchant vessels rescued the people, however, it took a lot of public and media pressure to allow for their disembarkation in Europe. Surprisingly, the Italian-flagged Asso 29, owned by the Italian company Augusta Offshore, conducted three rescue operations and quickly disembarked the migrants in Italy – in one of these cases, the migrant boat was in distress in the Libyan SAR zone. In this case, Italian authorities argued they had to coordinate the rescue because no other authorities were either reachable, available, or taking responsibility.

At the beginning of July, the livestock carrier Talia rescued 52 people who were in distress in Malta SAR zone. The captain Mohammad Shabaan showed much solidarity to the people in distress, and despite harassment by authorities, he always stood up claiming his pride for having rescued people in distress at sea, in line with international law as well as maritime ethics. After five days of standoff at sea, and thanks to the efforts of the Talia crew, to the captains’ outreach to international media, and the pressure exercised by several civil society organisations, Maltese authorities assigned them a port of safety.

On 24th July, The Italian flagged Merchant Vessel Cosmo rescued 110 people and could quickly disembark them in Pozzallo, Sicily, although Malta had taken responsibility for coordinating the rescue operation. A few days later, on the 5th of August, the Maltese authorities coordinated the rescue operation of 27 people by the Merchant Vessel Etienne – of Maersk Tankers; however, in this case Maltese authorities refused to let them disembark. After 37 days at sea – the longest standoff ever recorded – the Mare Jonio – by Mediterranea NGO, intervened, transferred the 27 rescued on board of their rescue vessel, and brought them to Italy.

The case mobilised concerns and discussions amongst shipping companies. In an open letter published on 8th October, the European Shipowners Association (ECSA), International Chamber of Shipping and European Transport Workers Federation (ETF/ITF), demanded that “EU measures are needed on prompt and predictable disembarkation for persons rescued at sea by merchant vessels“. The Danish shipping company Maersk Tankers published an article on 21st December: “How does a shipping company deal with a political standoff? Maersk Tankers’ response to the Etienne crisis“. They wrote: “A ship’s captain should be able to save those in distress at sea with confidence that the relevant authorities will assist him to readily disembark the rescues. All this did not happen when the Danish-flagged Maersk Etienne saved 27 persons from a distressed boat in the Mediterranean Sea.“ Also the Talia’s Captain, Mohammad Shabaan, stood in solidarity with the Etienne and the 27 people rescued, and shared a powerful message demanding their disembarkation.

The case of the Italian shipping company Augusta Offshore

On 29th July, the Italian vessel Asso 29, in service to the Eni oil platforms, rescued 84 migrants in Maltese SAR from a raft, which had almost sunk, and brought them to Lampedusa. The boat had alerted Alarm Phone, and was spotted and monitored by the Moonbird crew. Amidst the silence and lack of response by the Maltese authorities, the Italian Coast Guard, eventually took over the coordination of the rescue. After more than 80 hours of non-assistance, the Asso 29 rescued the people in distress. However, it was too late for 3 people who had already jumped in the water out of desperation. The survivors were then disembarked in Italy. Also on 1st September, MRCC Rome sent the Asso 29 to rescue a boat with 18 people in distress 40 nautical miles south-east of Lampedusa, as all coast guard units were in the port. A few weeks later, on 9th October, Asso 29 conducted another rescue operation, for 4 out of 5 people who were in distress near the Bouri oil platform – in international waters – and brought them to Lampedusa. The fifth person reported to suffer from serious health problems, was evacuated and taken back to Libya by a helicopter.

The potential background for these unexpected rescues by Asso 29, could be the threatening ongoing criminal court case against the Augusta Offshore company and the captain of Asso 28, another vessel owned by this company. In July 2018, the Italian-flagged merchant ship Asso 28 had rescued more than a hundred migrants, including minors, in international waters off the Libyan coast, brought them back to Tripoli and handed them over to the Libyan coast guard. The public prosecutor’s office in Naples is bringing the Asso28 captain to trial for illegally pushing back the people to Libya. This is the first trial of its kind in Italy.

Documents show that the crew of the Asso 28 did not inform the Italian Maritime Rescue Coordination Centre (MRCC) about the rescue operation – although Italian-flagged vessels are under Italian jurisdiction. The company stated that the rescue had been coordinated by the Libyan authorities. However, according to research by the Italian investigative journalist Nello Scavo, this was not confirmed during the investigations by the public prosecutor‘s office, which used audio recordings of radio communication between Asso 28 and Open Arms as evidence.

According to ASGI, there are clear similarities between what has happened in this case and the events of May 2009, with the refoulements coordinated by the Italian authorities, and later condemned by the European Court of Human Rights (Hirsi v. Italy, judgment of 23rd February 2012). The association calls on all Italian institutions, the European Parliament and the European Commission to shed full light on the role played by the MRRC Rome in pushing people back, to shed light on this matter and to take necessary initiatives so that similar episodes are not repeated.

Italy: between ongoing rescue gaps, closed harbours and quarantine ships

Moby Zazà quarantine ship in Porto Empedocle, Sicily, 6 July 2020. Foto: Giovanni Isolino, Afp

Moby Zazà quarantine ship in Porto Empedocle, Sicily, 6 July 2020. Foto: Giovanni Isolino, Afp

Against the background of 34,133 people who reached southern Italy by sea in the whole of 2020 (more than 180% more than in 2019, see UNHCR, 2020), more than 32.000 people arrived in the second half of the year, while only about 2100 in the first 6 months. As usual, Libya (13,139) and Tunisia (14.719) were main countries of departure, but we also observed about 1,390 arrivals from Algeria to Sardinia, and about 4,885 arrivals from other countries of departure, including Turkey.

The route from Algeria to Italy dates back to 2006 and since several years it was not used. During the second half of 2020 relatives reached out to us for around 10 cases of missing boats having left from the region of Annaba in an attempt to reach Sardinia. At least 2 of these boats were returned to Algeria after having been rescued by the Algerian Marine but most of them made it autonomously to Sardinia.

In comparison to the first half of 2020 both autonomous landings from Tunisia and arrivals following SAR operations increased.

Rescue politics in the Central Mediterranean have continued to be characterized by the so-called “rescue gap”, due to a very limited presence of institutional SAR assets in the area and the administrative seizure of most NGO ships.

Despite Maltese and Italian SAR authorities’ general unresponsiveness, and the usual referral of distress cases to the so-called Libyan Coastguard, we observed at least one significant case of rescue coordinated by the Italian Coast Guard in Libyan SAR zone. As outlined in the previous section, between the 28th and the 29th of July, MRCC Rome authorized the Asso 29 ship to rescue 84 people on a rubber boat and to bring them to Italy. In the press release they justified their intervention with a “persistent lack of response by and availability of “other coast-guards”.

The legal framework restricting Italian territory to migrants which was built during the first months of 2020, after the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic, remained in force from July onwards. Important developments in this area were: i) the inter-ministerial decree of the 7th of April 2020 which defined Italian harbors as “not safe”, for migrants rescued outside of Italian territorial waters by non-Italian flagged ships; ii) the related civil protection decree which established the “quarantine ships system”, and identified the Italian Red Cross as managing body.

Even if justified as a health-related measure aimed at preventing the diffusion of the Covid19 pandemic, the quarantine ships were a further escalation of the declaration that Italian harbors were unsafe for migrants. In the second half of 2020 the Italian government deployed 6 ships —the Allegra, Azzurra, Adriatico, Superba, Suprema and Rhapsody— each with a capacity to host 250 people. More than 150 associations in Italy and Europe, including Alarm Phone, signed a document titled “Critical issues in the quarantine ship system for migrants” which highlighted the main issues of the quarantine ships system. Beyond the discriminatory nature of such a policy, main critical points were identified as being related to the limitations of access to asylum – due to the limited provision of information on asylum procedure at the Hotspot and onboard – and the automatic channeling of a number of nationalities (i.e., Tunisians, Egyptians) into deportation procedures. In addition, associations denounced the inadequacy of quarantine ships to host shipwreck survivors and vulnerable persons, such as minors and pregnant women, due to the lack of access to specialised health care and assistance.

Despite the hosting capacities of Italian reception system – which currently has vacancies due to the decrease of arrivals – only very few migrants were transferred to reception facilities on land to undergo isolation measures. Amongst migrants who were allowed to disembark, were the 27 migrants who were transshipped on the Mare Jonio after more than 1 month of off-shore detention onboard Etienne cargo, in September 2020.

Finally, during the second half of 2020, Italian courts continued to be a battlefield concerning the criminal prosecution of NGOs. Following the decision on the Vos Thalassa case on the 23rd of May 2019— in which the Trapani court absolved the 2 migrants who had strongly protested against their return to Libya on board the commercial vessel, by recognizing their behavior as being in compliance with the protection of right to life (art.2 ECHR)— and the Cassation court decision on the Carola Rackete case of February 2020 —in which her arrest was judged as illegitimate and her behaviour in compliance with the duty to rescue— in December 2020 the courts of Ragusa and Agrigento respectively took decisions which were in favour of the NGOs Open Arms and Mediterranea Saving Humans. In particular, in the Open Arms Case, the Ragusa Judge for Preliminary Inquiries (GIP), stated that Libya – being the theatre of systematic human rights violations – could not be considered a Place of Safety and that the delivery of the migrants rescued by Open Arms to Libyan authorities would have constituted a collective expulsion. The Agrigento Judge for Preliminary Inquiries (GIP) decided for the closure of the criminal proceeding against Mediterranea Saving Humans, by assessing the order to stop operations given to the NGO by a Frontex vessel as illegitimate. The judge considered the Captain’s refusal to follow the order as compliant with international maritime law and with his duties as commander of the vessel.

Tunisia’s coast under European big brother’s radar

With a 1,300 km long maritime border, which in some places is only 140 km from the European coast, Tunisia has long been seen as a key partner for controlling crossings on the Central Mediterranean route. In recent months, Tunisia has been the focus of much attention due to the increasing arrivals in Europe of Tunisian Harraga. According to The FTDES, a Tunisian NGO, in 2020, 12883 persons arrived in Italy and 13466 were intercepted and brought back to Tunisia.

The attention on Tunisia increased substantially after the terrorist attack in Nice in October 2020, with European political leaders lumping terrorism and migration together once more. Visiting Tunis in November 2020, the French and Italian interior ministers expressed their willingness to strengthen cooperation with Tunisia to lock its maritime borders in the name of the fight against terrorism. Among other measures, they promised to bolster naval and air surveillance to help the country to monitor its coasts.

These means of surveillance only add to an already colossal edifice of maritime border control. Since the Ben Ali era, European countries, spearheaded by Italy, have been cooperating with Tunisia to multiply interceptions at sea. Over the last thirty years, several dozen patrol boats, 4X4s and helicopters have been given to Tunisia in exchange for tighter collaboration on border control. For several years, the EU has also been working to strengthen the data collection capacities of the Tunisian Maritime Guard. As part of a two-part project entitled “Integrated border management” launched in 2015 (funded by the EU Emergency Trust Fund for Africa), the Tunisian Coast Guard has been equipped with ISMaris, an integrated maritime surveillance system able to collect real-time data on migrant boats at sea.

Tunisia is also part of the European border surveillance system Eurosur, managed by Frontex. The system is based mainly on satellite images collected by the European “Copernicus” programme, but also on images collected by the European Maritime Safety Agency (EMSA), which are recorded by drones and soon by aerostatic balloons. In addition to the European coasts, more than 500 square kilometres of “pre-border regions”, of which Tunisia is a part, are monitored by the Eurosur system.

In 2018, the European Commission confirmed that Frontex was monitoring the Tunisian coast using satellite images and radar during a test phase of “Eurosur Fusion Area Pre-Frontier Monitoring”, stating that test flights of drones were being carried out in the region (Algeria, Tunisia and Libya) for surveillance purposes. In the framework of the Seahorse Mediterraneo 2.0. project, the data collected is intended to be shared with the Tunisian “coastguard”, as is already the case with the so-called Libyan coastguard.

In recent years, surveillance of the EU’s “pre-border” areas has become a central externalisation strategy, responding to a logic of early interception already at the heart of European cooperation with the so-called Libyan coastguard. The aim is simple: to detect boats as early as possible in order to alert the Tunisian authorities so that they can take charge of maritime interceptions themselves, bringing people back to countries that can in no way be considered “safe” and from which people on the move are desperately trying to flee. Alarm Phone has long denounced this strategy of proxy refoulement, which violates international law and the fundamental rights of migrants. These illegal attempts to relieve European coastguards of their search and rescue obligations only result in more cases of non-assistance and shipwrecks.

Despite the dismal results of this strategy, the EU and its Member States seem determined to continue with it. A few months ago, in October 2020, a 50 million euro contract was signed between Frontex and Airbus and Israel Aerospace Industries (IAI) for a “Maritime Aerial Surveillance with Remotely Piloted Aircraft Systems (RPAS)” programme. At the same time, the Italian Ministry of the Interior signed a 7.2 million euro contract (half of these funds are allocated by the European Commission under the Internal Security Fund) with the Italian arms company Leonardo to deploy drones to monitor departures from Libya and Tunisia. The information collected by the drones is also to be fed into the Eurosur surveillance network operated by Frontex.

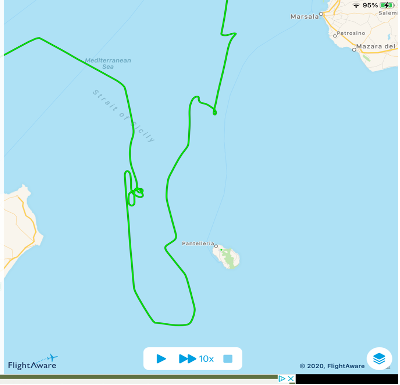

On December 3, Frontex aircrafts, based in Trapani, started to monitor the Tunisian route. Since then, they have flown several missions. Their tracks can be found on the pictures below:

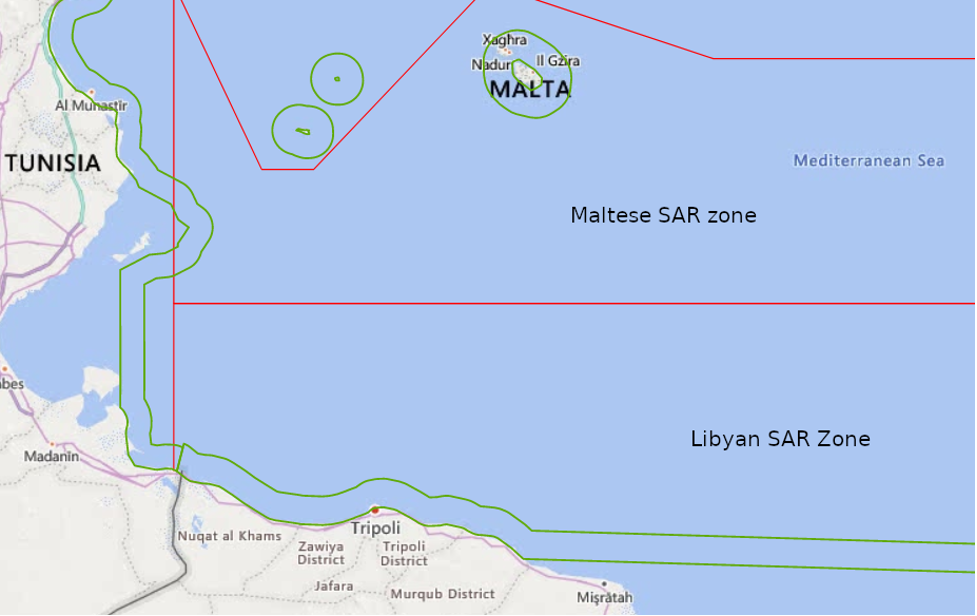

MALTA – LIBYA: 139 Nautical Miles of Non-Assistance

139 Nautical Miles is the distance between Zuwara in Libya to the Italian Territorial Waters of Lampedusa (green line), just north of the Maltese SAR zone. Foto: Alarm Phone

139 Nautical Miles is the distance between Zuwara in Libya to the Italian Territorial Waters of Lampedusa (green line), just north of the Maltese SAR zone. Foto: Alarm Phone

Malta never publicly revoked their announcement from April about the closing of ports and the stop of search and rescue operations by the Armed Forces of Malta (AFM) due to COVID-19. The government obviously intended to reduce the number of migrant arrivals in 2020 drastically (2,281 people overall reached Malta according to UNHCR, compared to 3,406 people in 2019). An observation further confirmed by the fact that no NGO-vessel got assigned a port to disembark in Malta in 2020.

The Easter pushbacks organized by Malta with the help of private chartered vessels caused 12 deaths and international criticism.The public pressure pushed the government to change their anti-migration-policy slightly: since April AFM started reacting to distress alerts again, but rescued migrants were not allowed to enter Malta and were detained on “floating prisons” – chartered vessels outside Maltese territory. Only on the 6th of June were all 425 detained people – some of whom had been kept on the vessels since the end of April – were finally allowed to disembark in Malta. It was reported that the Maltese government spent 1.7 Mio Euro on this detention policy.

From July to December 581 people overall arrived in Malta (compared to 2,130 people in 2019 over the same period). Most of them – a total of 436 people from 7 boats – had called the Alarm Phone. For each boat, Alarm Phone had to struggle before AFM finally reacted. They either refused to rescue or to later disembark the people in Malta. Instead, for several boats that alerted us, RCC Malta ordered a merchant vessel to monitor the people in distress. We experienced several times in the past that boats in the Maltese SAR are illegally ‘chain’ pushed-back to Libya, under RCC Malta’s supervision. We are therefore pleased that thanks to public pressure it was possible to prevent some of these unlawful returns in the second half of 2020.

On the 4th of July, 52 people alerted Alarm Phone that they were drifting in the Maltese SAR zone. AFM didn’t arrive for rescue, however the livestock carrier Talia sheltered the migrants and later took them on board when the situation on the boat worsened. Both Italy and Malta refused to transship the migrants or to assign Talia a port of disembarkation. Only thanks to the crew and captain and huge public pressure were the 52 people finally allowed to disembark in Malta, after 3 days kept in unworthy conditions off Malta’s coast.

On the 5th of August, 27 people in distress alerted Alarm Phone in the Maltese SAR zone. Again instead of AFM, a merchant vessel intervened: The MAERSK Etienne under Danish flag finally rescued the people when the boat began to sink. Malta refused the disembarkation of the 27 people. Only with the help of the NGO-vessel Mare Jonio was a solution found after 37 days: 25 people were finally brought to Pozzallo in Sicily on the 12th of September whilst two people had to be evacuated to Malta due to medical emergencies. The longest standoff in the history of sea rescues by merchant vessels greatly affected the 27 people already in a bad health condition, as well as the crew.

In some cases people in distress were in the end rescued by AFM, probably because of public pressure and – in addition – because neither a merchant vessel nor the so-called Libyan Coast Guard were available to do the dirty job of a push back to Libya. 65 people in distress who called us on the 16th of July were rescued by AFM after one whole day of non-assistance. 38 people who were drifting in the Maltese SAR zone on the 2nd of October were finally rescued by AFM to Malta, as they failed to fix the boat’s engine – probably hoping that the boat would continue to Italy as experienced several times already. On the 3rd of October AFM again rescued 71 people in the Maltese SAR zone and brought them to Malta.

Most of the time boats in distress in the western area of the Maltese SAR zone, south of Lampedusa, do not receive any attention by AFM, despite RCC Malta being the responsible authority for this zone. There is a huge rescue-gap for boats in distress from the Libyan coast up to Italian territorial waters where MRCC Rome’s responsibility starts.

87 people were brought to Lampedusa by the Italian Coast Guard on the 27th of October after having been in distress in the Maltese SAR zone. A boat with 19 people capsized on the 20th of October in the Maltese SAR, 30 Nautical Miles south of Lampedusa. 5 people are still missing.

We will continue to remind Malta of their duty to rescue and will not accept their illegal practises, also in the future.

LIBYA: HOW THE EU KEEPS DELEGATING HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS AND FINANCING DEATH AT SEA.

Sudanese protesters at the UNHCR office in Guruji. The picture was shared with Alarm Phone by one of the protesters who wishes to remain anonymous.

Sudanese protesters at the UNHCR office in Guruji. The picture was shared with Alarm Phone by one of the protesters who wishes to remain anonymous.

Never before has the Alarm Phone received so many calls from Libya. Not only from people in distress at sea, but from people who survived shipwrecks, from people who lost their loved ones in shipwrecks, and from people who demanded our support to report on the situation on the ground. Although it is not amongst the Alarm Phone’s usual tasks to collect these testimonies, to look for missing people, to speak to relatives and to document the ordeals people are fleeing from, over the past months we felt we had no choice but to listen, document, search, report. We could not turn away, despite our lack of training, capacities and resources. We could not turn away because we realised there was nobody else listening. That survivors, relatives and witnesses call the Alarm Phone points to the expansion of the black hole in a region where people regularly disappear, drown, are tortured and kidnapped, whilst every organisation, governmental and non governmental, simply looks away.

International Organisations seem increasingly unwilling or unable to report on the violent conditions in Libya, let alone to investigate deaths at sea. It is left to activists and volunteers, including the Comitato Nuovi Desaparecidos, to keep track of shipwrecks and to document the lethal consequences of this violent border regime.

It is only thanks to the brave voices of people who are either trapped into this hell or who were forcefully brought back to it, that we have been able to document not only shipwrecks and deaths at sea, but also pushbacks, non-assistance and human right violations by EU authorities. Over the past 6 months, and throughout 2020, these voices have been powerful weapons against European border violence.

Back in April we reported how Malta murdered 12 people and illegally pushed back 55 people, in the so-called Easter Massacre. The events led to a national and international turmoil that, however, was quickly silenced and dismissed. The unintended consequences were yet another deal between the Maltese government and Libyan authorities, establishing a new joint rescue coordination centres, financed by the Maltese governments, that would facilitate interceptions of migrant boats before they reach European Search and Rescue zones, thereby further delegating human rights violations rather than putting and end to this violence.

The cease-fire, announced in August and implemented at the end of October, has not meant an end to the conflict, nor to people’s attempts to flee what remains a dangerous territory for migrants as well as for many Libyan citizens. On August 23 shootings by pro-government forces against unarmed civilians who were protesting the poor living conditions were reported in Tripoli. On October 6th, a Nigerian migrant worker was murdered by three men in Tajoura, near Tripoli. The young man was burned alive. Three other people also suffered burns. Two days later, on October 8, a group of Sudanese migrants protested in front of the UNHCR office in Guruji, Libya, against the lack of access to asylum, protections and to basic rights. As they explain in a video: “Some people need medical assistance, some want help, some are complaining about lack of protection, some were attacked in their houses and some were beaten up. Now we are in front of Guruji, but nobody came to speak to us or to listen to the people”.

Raids and arrests have taken place across the Libyan coast under the flag of ‘combating smuggling and illegal immigration’ during the past months. On August 15, the Tajoura Security Directorate conducted a raid in Banour district, Libya, and arrested a large group of migrants. Raids in the area of Garabulli pushed several people who would have departed from East of Tripoli towards Malta to travel to Zuwara or Zawiya in an attempt to reach Italy instead. In October, the UN-sanctioned Abd al Rahman al-Milad aka Bidja (affiliated with naval & Coast Guard in Zawiya) was arrested. The arrest of Bidja in Zawiya created a local power vacuum as well as violent struggles between existing militia groups that predictably immediately translated into an exacerbation of violence and harm towards migrant communities. This attempt to undermine local power structures did not prevent people from fleeing Libya. It just destabilised existing networks and routes, making the crossing even more precarious and dangerous.

Over the past 6 months, we were alerted to smaller boats in distress or missing boats, with about 15-20 people on board, that were not equipped for the journey, did not have satellite phones to reach out for help, or did not have geolocalisation devices. It is in these months that most shipwrecks were reported off Libya, where hundreds of sub-Saharan people and several Libyan people lost their lives. Many of these shipwrecks happened just off the Libyan coast, and could have been avoided if only authorities responded adequately to the distress calls.

The so-called Libyan coastguard operated dozens of pushbacks with the active support of Frontex air surveillance missions. During these interceptions, often people lost their lives under circumstances that were never investigated and clarified. Whilst the so-called Libyan coastguard is often quick in intercepting boats that are moving towards European Search and Rescue zones, or that are about to be rescued by NGO assets, the Alarm Phone has experienced that it often does not react when alerted to extreme distress situations of its coasts. This further points towards its function as a border control force rather than a coastguard. On October 15 a delegation from the Libyan Ministry of Interior visited France, and discussed the provision of a number of aircrafts for ‘search and rescue operations’, or rather, for further enabling pushback and capture operations. There were also reports that Turkey, the GNA and Italy’s ally, started to train the Libyan coastguard. Moreover, at the end of October, EU member states launched the so-called Operational Mediterranean Initiative (OMI) in cooperation with Libya, Tunisia, Algeria, Morocco and Mauritania to combat smuggling.

The EU and Italy clearly keep financing violations of human rights and delegating its responsibility for death at sea. We will not stop holding Europe accountable for each single one of these tragic deaths. We refuse to listen to narratives that estimate how deaths at sea are increasing or diminishing. Each single death is a death too many. And each single death is on you, Europe.

We have decided to end this report with two testimonies that people trapped in Libya wrote to Alarm Phone, as their powerful words perfectly express the current situation of people who are continuously pushed back to war, torture and harm.

Testimonies from Libya

Chronicles of a violent pushback

We left at 11pm, on June 24th. It was Wednesday evening. We were on a white rubber boat, 70 people, 69 men and one woman. Most of us were from Sudan, five people from Gambia, two from Ethiopia, and some from South Sudan and Chad. The woman was from Nigeria. We left from a beach nearby Garabulli.

The next morning, on Thursday, around midday, a small airplane appeared above us. I am not sure if it was a military airplane. It was small, while and grey. They saw us and then they left. At 6pm a helicopter came to us. At that time we were continuing well, the boat was good, we were all sitting comfortably, some people were sleeping and we had enough fuel. Around the same time also the same airplane that we saw in the morning came back. The helicopter came very close to the boat, opened a window and I could see with my own eyes two men wearing life jackets and waving at us. They were crossing their arms to tell us to stop. Around the same time we could see two vessels. One of them was a red and white boat, but it was in the distance. It was red on the upper parts and white on the down parts. The other vessel belongs to the Libyan coastguard. It was white. It had a number on it, from left to right: 648, and was written ‘Ras Al Jadar’.

When we saw the Libyans we had different opinions on the boat. Some of us wanted to increase the speed and run away. Some of us wanted to go towards the red ship, because we thought it was a rescue ship. We started heading towards the red vessel. The Libyans came and started to obstruct us. Wherever we tried to go, they were blocking us. The Libyans throw us potatoes, the normal potatoes we eat…. they were throwing them at us and we were throwing them back.

Then the situation escalated and we could not go to the red vessel. We changed direction and tried to go in the direction of Lampedusa. They came to us and blocked us again. Their vessel hit our boat and four men fell into the water. They could not come back to the rubber boat because we were moving very fast. We continued very fast, and the Libyans stopped. The vessel stopped for a bit and was going in their direction (of the people in the water), but did not see what happened to the four people who fell into the water.

A guy called the Alarm Phone, but he was speaking in French and I could not understand. When he called we were still on the rubber boat. The Libyans were chasing us, they were hunting us. The only thing he said in English is ‘we are dying’. Later I was holding the phone to call back Alarm Phone in English – but there was no network.

We were going very fast and then the Libyans unloaded a very small boat and started chasing us with it. The small boat moved very fast to change the direction of our boat. One man had a sharp metal object, another man was holding a paddle. When they reached us they started beating us with the paddle. The man with the metal stabbed our boat and our boat started losing air. They insulted us. Some of the guys on our boat started bleeding because of the attacks with the metal and with the paddle. They told us: ‘it is over, we are here to rescue’.

Then some of us moved to the back of the boat. They seized the engine and made sure the engine would not fall into the water. Until this point we were still on the rubber boat. Then they threw us a rope. One of them jumped into the rubber boat and forced us to go to the big vessel. There we found 200 other migrants. The Libyans collected the engine. We had car tubes to use as life-jackets. They took them and everything else that was valuable from the rubber boat. One of them took a knife and tore the rubber boat.

We were taken just a few minutes before sunset. Before we came back to the Libyan soil we moved again for about one hour and they caught another boat with 53 or 55 passengers. It was a white rubber boat. When we reached this other boat it was already dark. It was a white rubber boat.

Sea Watch’s aircraft Moonbird spotted the interception of this boat, and the picture clearly shows people in the water.

Sea Watch’s aircraft Moonbird spotted the interception of this boat, and the picture clearly shows people in the water.

Foto: Moonbird/VICE.

On the vessel I met only two of the four people who fell into the water. They were shivering from the cold. One of them told us he was beaten. The other two people I don’t know what happened to them. I did not see them and I did not hear anything. I cannot assume what happened. Everything is possible. One of them was Sudanese, the other guy I am not sure. I don’t know their names but I can call some friends who know them. On the vessel we were sitting on the front, and other people were on the top and on the back. We were separated from the other groups of passengers, but when we arrived in the port I could see that they were taking out many women, one of them was holding a small child.

When we arrived on land we were handcuffed and put in buses to go to Al Khoms prison. Some people jumped from the buses and tried to escape. Then the buses stopped and one guy told me: ‘you guys Sudanese, you are a source of problem. Your friends run away, why you don’t run. They beat me on the ground. I have wounds and scratches on my belly, on my knees and the rest of my body. I was still handcuffed, with plastic handcuffs. I managed to run away with the handcuffs, and I went to a place where someone cut them for me. I have pictures of the wounds. Now I feel better, as I took some painkillers. Now I am back to where I was staying.

I called Alarm Phone to tell you what happened to migrants pushed back to Libya, to warzone, who get beaten, tortured, put in prison and detention centres where they are forced to pay to get out. Some people are bought and sold as merchandise. I called Alarm Phone because you are an ear listening and to say to stop giving support to the Libyans. I saw that the helicopter had European Union stars. I saw it with my own eyes. European Union airplanes give the position of our boat to the Libyans to catch us.

Is this not corruption in the name of humanity? – A letter from Libya

Both the world and life turned their backs on us, no identity, nor home, nor safe life, everywhere we go the word illegal never leaves us. Everywhere we go, we face discrimination and people call us illegal or cowards who flee their homes.

Our governments expelled us from our home, and deprived us of our basic rights of life and education. In 2004, I was 2 years old when they started attacking and persecuting us, and expelled us from Darfur to a refugee camp in Chad.

For migrants in Libya the situation is very difficult, like we cannot go out from where we live, because when we go out we are subject to mock, provocation, insulting and sometimes Libyan kids throw us stones when we go in streets and sometimes they throw stones in the places where we live .. And also we typically cannot go out for work to gain some money to buy what we need to eat or water to drink or soap to wash what we wear.. sometimes we are forced to risk and go out in search of work in order to gain little money to buy what we need … but unfortunately sometimes when we get works we work with less payments, Or often when we finish work, they don’t pay us and instead they sell us to the police who puts us in prison for months, then ask us to pay money to free ourselves from prisons, and there’s people who are forced to call their family to ask them to pay money to release them from prison, and there’s people who hesitate to ask for money from their poor families who they are living in difficult conditions so they prefer to stay in prisons but they never let their families know nothing of all what they facing in Libya.. really the life is very harsh, but we keep silent because we don’t know to whom we should complain..

I don’t know about other refugees and migrants, but for me, I have tried four times to flee Libya. two times when we see Libyan coast guards we jumped in the water to not be taken back to Libya, and one time we when Libyan sea guards came, we refused to get one their ship, but the stab our boat, and waited till our boat sunk and we jumped in water then they started save us in slowly.. i really don’t know how about others, but for me, I prefer death in the sea instead of live hellish life in this murderer country, because here in Libya we are not respected and around 95 percent of Libyans looks at us not as human beings, and often they would come to where we live and take all what we have forcibly at gunpoint.. fleeing our home and illegal immigration aren’t in our wishes or dreams, but this situation is forcing us to flee.

The staff of UNHCR in Libya, they are not performing their jobs. UNHCR in Libya is very slow and its staff are not serious in what they are there for, and their slowness is the main reason that pushes asylum seekers and refugees to flee Libya via the Mediterranean. They don’t know where we live and how we live. And whether we are alive or dead. And when we go to their office center to ask help, they don’t allow us to enter the center, they put us under the blazing sun in unsafe streets, they don’t even try to hear what we want to say, or what we want to report about,. they just give us invalid numbers and tell us to call them to take appointments, but when we call them they don’t answer our calls, and when we send messages to her, they ignore us .. Really, the staff of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees in Libya are inhuman people working in a humanitarian organization, they live In luxury only through the money that the institution of UNHCR and other humanitarian organizations pay them to serve everyone in need,..

Is this not corruption in the name of humanity?