After the EU-Turkey deal and the blocking of the Balkan Route, the Aegean islands turned into prisons

Marion Bayer and Lisa Groß

From January until August 2017, a total of only 4.000 people arrived on the island of Lesvos, while the number of crossings in the entire Aegean Sea was 12.000. Due to this small number, also our engagement with boats in the Aegean decreased. Nevertheless, we are still regularly contacted by people on boats in distress attempting to cross from Turkey to Greece. Through these direct exchanges, we could witness a massive and painful rollback that changed the face of Lesvos and many other islands in the Aegean.

Starting with the EU-Turkey Deal in March 2016, deportations from the Greek islands back to Turkey were launched, framed as part of a legal deal. In the beginning, deportations happened less often than expected – people fought back by applying for asylum in Greece and by documenting the problems they had been facing in Turkey. The public and media attention on the deportations therefore slowly faded away, but currently, deportations are again taking place on a regular basis: Every Thursday, a boat with deportees leaves from Lesvos and deportation flights are also carried out from time to time.

Since the deal, the situation has worsened dramatically: thousands got stuck in terrible conditions in the so-called hot-spots, so that the islands have turned into large prisons. At the same time, thousands got stuck also on the Greek mainland, when the official and controlled corridor along the Balkan Route was closed from the beginning of 2016, step by step. Legally, refugees in Greece have the right to reunite with their families in other European countries, with most of them having relatives in Germany, but the processing of family reunifications became incredible slow. So people were waiting for several month, sometimes years, in inhuman living conditions, locked up in hot-spots and camps where they can neither be heard, nor seen.

A relocation-program, which was launched with many promises, resettled only a quarter of the announced 63.000 people from Greece to other EU countries until today. Finally, the EU Commission even recommended to slowly restart the Dublin-returns to Greece – after the returns had been halted for more than six years, following a decision of the European Court of Human Rights, which considered the conditions for refugees in Greece as inhuman. The announcement came precisely at the time, in December 2016, when five refugees froze to death in their snowed in tents in the Greek hot-spots while others died of smoke poisoning in an attempt to warm up their tents.

Unforgotten: the summer and autumn of 2015

When we described the incredible transformation of the Aegean border region in our first Alarm Phone brochure in November 2015, more than 56.000 people had reached the island of Lesvos within only one week. We had been in contact with 100 boats during that week from 26th of October until 1st of November. It was at the peak of this extraordinary year of 2015 – toward the end of “the summer of migration”. Through the Alarm Phone, we were in contact with more than 1.000 boats in the Aegean Sea in 2015. This incredible situation will never be forgotten, it is still vivid in our collective memory and this is also why we chose to narrate the meeting with Safinaz in this brochure, the woman whose WhatsApp chat we had reprinted in our first anniversary brochure.

Sea-Watch 1 in the harbour of Mytilene/Lesvos, showing solidarity with Jugend Rettet, September 2017 (Photo: Marily Stroux)

Refugees were welcomed at their arrival, boat by boat, not only by the local residents of Lesvos, whose laudable efforts gained attention worldwide, but, latest from August 2015 onwards, also by people from all over the world, who came to Lesvos to help. In summer 2015, more and more initiatives became involved also in rescue operations, including anarchist groups from Athens, life-guards from Spain, Médecins Sans Frontières (Doctors Without Borders) who cooperated with Greenpeace, a German boat from Sea-Watch, and many others. At that time, push-backs and violence at sea seemed to have nearly disappeared in this part of the Mediterranean.

Not everyone has left…

In the beginning of 2016, authorities began to pressurise activists and volunteers assisting and welcoming refugees at the beaches into registering with them. Activists from Denmark and Spain were criminalized for their courageous effort to save lives at sea. Since then, only NGO’s who cooperate closely with the coast guards and Frontex are officially allowed to be present there. Nonetheless, some others resist the pressure and still remain present.

The shores of the European Union have been militarized like never before. NATO warships patrol the entire coastline. While they hardly ever intervene directly, their radars detect most of the movements at sea, and once detected, they alert the Turkish authorities to intercept refugee boats. Interceptions and transfers back to Turkey occur on a daily basis. In addition to the Greek and Turkish coast guards, Frontex units patrol at sea. Police, military and Europol are active on the Greek islands. Those who finally make it across, report that they have attempted to cross the sea several times until they finally made it. Today’s crossings are again prepared in a completely clandestine fashion. Nothing is visible anymore, which also means that sea crossings are – compared to 2015 – becoming increasingly dangerous again.

Push-backs still exist but violence is not (yet) systematic

The clock has not simply been turned back – the situation is not like before 2015, when everyone who came anywhere near the ‘arrival’ beaches at night, ran a high risk of being criminalised. Still today, some NGO’s remain on the spots to observe the shores. Volunteers are still travelling to the islands to support, and local people still remain alert, not only on Lesvos but also on the other Aegean islands. While fewer are monitoring the situation now, there are still lively observations of what is happening at sea. This might be the main reason why push-backs by the Greek coast guard and by Frontex still remain exceptional and, for now, it seems like the old practice of daily push-backs enforced with brutal methods and even torture are not returning.

While the political forces within the (border) system have remained more or less the same for many years, it is clear that also some liberal forces exist within. While Syriza played a dirty role in turning the Aegean islands into prisons, thereby fulfilling their part of the EU-Turkey Deal in a shameful way, at least the most gruesome acts of violence at sea, perpetrated by the Greek coast guard, have decreased. Yet, this doesn’t mean that there is no violence at all: the border region is being heavily militarised and leaving someone in a small plastic boat in the hands of the Turkish coast guard to be intercepted and forcing them into risking their lives once again, can be called nothing else than an act of violence.

When we speak of the most awful forms of violence that we have learned about, we mean cases of waterboarding, guns pointed to the heads of people, brutal beatings and stabbing of boats. We shouldn’t forget the drowning of three women and eight children, who were killed when their boat capsized in January 2014 while being pulled by the Greek coast guard back to Turkey with a rope, driving at full speed. It’s important not to forget that even this was possible at Europe’s borders. It is the same coast guard that operates today – no one was sentenced for these crimes.

The push-backs did not fully disappear. We got called several times by people who got attacked at sea by coast guard members, who had only minutes or hours before been threatened by masked men, who had their engine stolen or their boats stabbed and who were left sinking in the middle of the sea. Nevertheless, push-backs don’t happen systematically anymore – and this is from our point of view a clear result of the increased attention due to the presence of civil actors.

In the article ‘Particularly Memorable Alarm Phone Cases’ in this brochure, we describe a violent push-back operation from June 2016, where even Frontex was present at the scene. While in this case the public reaction remained nearly absent, despite coverage in a national newspaper in Germany, in a more recent push-back case, the Greek media reported on it repeatedly, forcing the Greek coast guard to respond. It was on Friday, 21st of July 2017, at 5.03 am, when the Alarm Phone shift team was alerted to a group of 26 travellers, amongst them 2 children and a pregnant woman. We received a GPS-position, showing that they had reached Greek territorial waters. Not even one hour later we were informed that the Greek coast guards had been trying to return the boat to Turkey. A video showed the boat of the coast guards circling around the travellers, creating waves, which resulted in water entering the boat.

The next day we managed to reconnect with the travellers. They reported that the coast guards had been very offensive by creating big waves that caused their boat to rock left and right. On the coast guard vessel, men were wearing black and carrying weapons. Water started coming into the boat and the passengers started panicking. Although they pleaded with the Greek coast guards, declaring that they had a sick child with them who needed medical treatment, the Greek coast guard insisted on sending them back to Turkey. Fearing for their lives and those of the children they had on board, a paralyzed child and an 8-months-old baby, they went back to the Turkish coast where the Turkish police showed up to pick them up. Apart from the boat of the Greek coast guard, the travellers informed us that another boat with a Greek, French, Croatian and German flag painted on it was present during the pushback but did not intervene.

The Greek coast guard obviously lied in their statement following this incident. They declared that the boat of the refugees was still in Turkish waters when they arrived, but according to the position we received, the boat had already entered Greek waters. They declared that they only observed the boat and didn’t touch it but the video taken by the travellers clearly shows the Greek coast guard boat approaching them and creating waves to scare them. Finally, the coast guard even informed a Frontex vessel, which was actually present at the scene according to the testimonies of the refugees, but apparently, they only watched the push-back unfold.

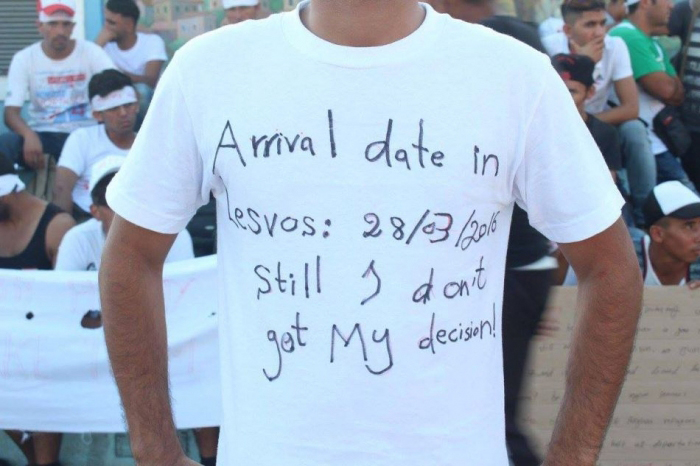

Afghan refugees protest on Sappho square, after being stuck in the Hot Spot Moria/Lesvos since many months (Photo: Arash)

While this case shows that these violent practices still exist, it also goes to show the obstacles the authorities face, when they continue to use these violent methods. Different to before 2015, more refugees know about the importance of documentation today. In this case, it did not help them directly, but they immediately documented and reported the violence and spread it around the world. Also different than before 2015, they found people to accompany their trip via the internet. Still today, some of the Syrian and Iraqi groups formed during the “summer of migration” who closely accompanied and monitored sea crossings, exist and do their best to empower the travellers. Finally, there are groups like the Alarm Phone, ready to support those on the move and to make acts of border violence public.

The reduced level of violence used against refugees at sea is the clear result of the presence of critical civil society forces. In times of militarisation, our presence is more needed than ever, especially when the bigger NGOs turn away from these border zones. Sea-Watch has fortunately decided to relaunch its activities in summer 2017, and returned with a “Monitoring Mission Aegean” to observe and document the massive and detrimental impact of the EU-Turkey Deal on the human rights of travellers. Besides them, many others also decided to stay.

How the islands turned into large prisons

All sorts of international NGOs work inside the overcrowded hot-spots to keep them running, in close cooperation with EASO (European Asylum Support Office), Frontex and the Greek police. The prisons became separate worlds, with their own rules, a machinery of separation. People who newly arrived and wait for registration, are detained in a closed part of the camp, the ‘inside’ of the inside. Latest after 25 days, they will be allowed to leave to the ‘outside’ of the inside, to the open part of the camp. Unaccompanied minors are detained in a distinct section of the prison, where they have to stay much longer, for their own ‘protection’, until a place in a youth accommodation is found for them, sometimes only months later. Detained are also all those who are “ready to be deported”, and, in another closed section, those who have, in great desperation, signed the agreement to be “voluntarily returned” to Turkey. In every corner of the camp you feel how the management of this self-created crisis has turned into a huge business. While volunteers are still present, everyone who enters, even into the open part of the camp, is registered properly with one of the NGOs. It is forbidden to take pictures. It is forbidden to distribute information. The refugees stuck on the islands keep asking desperately about their future – and there are few answers to all their many questions.

Nearly every day there are outbursts of violence due to the living conditions and long waiting times for registration, also among different ethnic groups, often related to the use of the limited space in the overcrowded camp. The hot-spot Moria on Lesvos burned down twice already – but there seems to be no response, hardly any signs of solidarity, and so these upheavals end with several arrests. On Tuesday, 18th July 2017, 35 refugees were arrested in Moria following a protest in front of the EASO-office where people showed banners denouncing the dehumanising conditions and called for freedom of movement for those kept on the island for over 6 months. Following this peaceful protest, there were clashes between some protesters and Greek riot police. Police forces carried out raids and arrested 35 people, who then got heavy fines and were transferred to prisons on the Greek mainland.

The many NGOs present in the hot-spots create the illusion of assistance and support, while they actually became part of a cruel system that reinforces the misery of all those who are denied the possibility to find the protection they so urgently need. Their suffering seems to be produced in an “ordered” fashion and this technocratic system of dispersed violence becomes ever-more difficult to contest.

The harbour of Mytilene

Over the last years, we took uncountable pictures at the harbour of Mytilene, Lesvos. Farewell pictures of those who left, who were excited to take the next step towards their desired final destination. Welcoming those who are in transit means wishing farewell to them, and hoping to meet soon again, hopefully in a safer place somewhere in Europe. For us, the harbour of Mytilene was a symbol, one crucial part of the journeys of thousands.

Today, fences surrounding the harbour have destroyed this Aegean point of arrival and farewell. It is not a lively space anymore. While police and Frontex are everywhere, occupying the space, strict entrance controls prohibit people without tickets to even enter the harbour. To complete the miserable scenery, police vans carry prisoners from the mainland to be deported back to Turkey from here.

Collectively we should resist EU authorities who try to turn the Aegean islands, known for their hospitality, into a symbol for Europe’s deterrence policies and stand against all attempts to turn Lesvos into a deportation hub back to Turkey.

Mytilene harbour in October 2015. Overcrowded with people who move towards the open Balkanroute (Photo: w2eu)

Family protest for faster family reunification to Germany. Athens, September 2017 They are waiting for many months, separated from their parents and partners (Photo: Salinia Stroux)

[This text is part of the recently published Alarm Phone brochure “In solidarity with migrants at sea!”]