The new Pact on Migration and Asylum (PMA) and its impacts on countries of the Western Mediterranean and Atlantic route

Anti-PMA protesters in Madrid, April 2024. Source: Activists

Content

Introduction

1. Sea crossings & statistics

2. What is the PMA (European Pact on Migration and Asylum)?

3. Spain & the Canary Islands

4. The Atlantic Route (Sahara, Senegal & Mauritania)

5. Morocco (Tanger/Ceuta/Gibraltar & Nador/Melilla)

6. Shipwrecks & missing people

Introduction

The European Pact on Migration and Asylum (PMA) represents the EU member states’ and institutions’ vision of migration, formalised as a legally binding document for EU member states. Alarm Phone, alongside many civil society organizations, bluntly describes this vision as racist. The European Union perceives (im)migration – particularly that of racialised people from poorer regions where dominant religious beliefs or culture practices differ from its own – as a threat. The PMA is another measure aiming to fortify its borders against illegalised people on the move. While it builds on previous European migration policies, the PMA intensifies a security rationale, legitimises human rights violations at borders, and undermines the right to asylum at the regional scale.

As Emma Martín, a campaigner for the rights of migrant people, states:

“If there is anything truly new, it is precisely this degradation of the values and moral principles that underpin the founding character of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union.”

In the EU, the hegemonic discourse often frames migration as dangerous and exceptional, disrupting a supposed normality without any migratory flows. Media and institutional discourse frequently use terms like “waves,” “episodes,” or even “crises” to depict migration as a threat requiring extraordinary measures. This narrative justifies border militarisation, while concealing real motives behind claims of humanitarianism.

With the PMA, the EU is endorsing a degradation of human rights standards. Borders are even more becoming zones of violence, justifying arbitrary arrests, detention (children included), surveillance, and forced displacement. These rights violations do not end at the border but extend throughout the EU. The erosion of migrant rights also threatens the fundamental rights of EU citizens, especially those involved in defending and supporting people on the move, who face criminalisation for acts of solidarity. Furthermore, the agreements signed with North and West African countries (often named as countries of origin and transit or as third countries in EU colonial jargon) to control migratory flows result in human rights abuses and violence for which the EU claims no responsibility, as they occur outside its territory. In fact, it is European migration policies and funding, with the active collaboration of Southern states, that lead to these violations, including detentions, deportations, and police brutality, resulting in the deaths of thousands of people and immense suffering for thousands of others and their families.

In the near future, we can expect further militarisation and externalisation of borders (e.g. Frontex, Spanish Guardia Civil in Africa, Moroccan and Mauritanian police in the Canary Islands), more detention centers in countries of the geopolitical South, and the continued criminalisation of migration in both countries of arrival and departure. With increased coastal surveillance and control, we can also expect more deaths at sea.

This regional analysis aims to explore the possible impacts of the PMA on the Western Mediterranean and Atlantic route, the reactions of local governments, and potential future developments. As usual, this analysis presents an overview of crossings and Alarm Phone cases from the beginning of April to the end of August 2024 (Section 1). Section 2 examines the PMA and its implications, followed by an analysis of the Pact’s effects in Spain (Section 3.1), particularly in the Canary Islands (Section 3.2). Section 4 covers the Atlantic route, with a focus on Sahara (4.2), Senegal and Mauritania (4.3), and Morocco (5), especially the regions of Tangier, Ceuta, Gibraltar (5.1), Nador, and Melilla (5.2). Unfortunately, it was not possible to include a section on Algeria in this report, due to lack of information and resources. Section 6 lists those who did not survive — our thoughts are with them, and our respect and solidarity go out to their families and friends.

As Alarm Phone, we focus this regional analysis on key developments and laws restricting freedom of movement, especially for racialised people, to better resist these injustices. We stand radically opposed to systems that legalise violence and criminalise both human mobility and solidarity. Security policies will never stop people on the move from exercising their right to free movement. Alarm Phone celebrated its 10th anniversary on 10 October 2024 and we remain committed to standing with people on the move and to fight against borders on a daily basis.

Ten years Alarm Phone – activists during a CommemorAction in Senegal 2024. Source: Wane Helice

1. Sea crossings & statistics

Between April and August 2024, Alarm Phone received alerts concerning 37 distress cases along the Western Mediterranean and Atlantic routes. Of these, 14 boats were navigating the Atlantic, while another 13 were attempting the journey from Algeria. A smaller portion, less than one-third of the total (9 boats), were crossing via the Alboran Sea. Only one case involved an attempt to reach the Spanish peninsula through the Strait of Gibraltar.

Of the 37 cases in which Alarm Phone was involved, nine boats were rescued by Spain’s maritime rescue service, Salvamento Marítimo. Six boats were intercepted and returned to Algeria, Morocco, or Senegal. In seven cases, the fate of those on board remains unknown to us, such as a boat that departed from Nouakchott, Mauritania, in early June. Despite the involvement of relevant authorities, no further information has been uncovered about the 130-150 missing people from that voyage. Tragically, many more individuals are either missing or presumed dead on this perilous route, which remains one of the most dangerous migration paths in the world. (For further details, see Sections 4 and 6.)

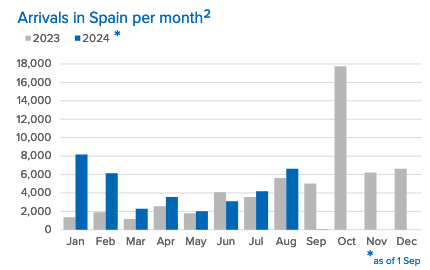

According to UNHCR data, as of 1 September 2024, a total of 36,062 people have arrived in the Spanish state this year. The majority of these arrivals—25,524 individuals—chose the route to the Canary Islands. While there was a sharp 279% increase in arrivals by the end of March compared to the same period in 2023, the number of arrivals stabilised over the summer of 2024.

Arrivals in the Spanish state per month. Source: UNHCR SPAIN Weekly snapshot – Week 35 (26 Aug – 01 Sep 2024)

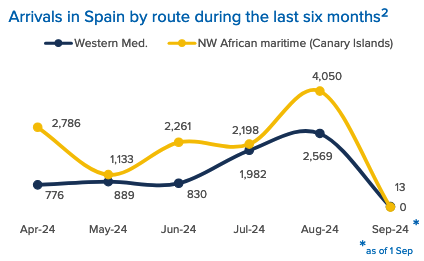

In fact, we observed a notable decline in activity along these routes. The UNHCR reports that since April, 19,487 people have arrived in the Spanish state, with numbers peaking in August before dropping significantly.

Arrivals in Spain by route. Source: UNHCR SPAIN Weekly snapshot – Week 35 (26 Aug – 01 Sep 2024)

For Alarm Phone, the cases we handled between April and end of August involved at least 1,410 people. However, it is important to acknowledge that many more people remain unaccounted for.

We are deeply concerned about the developments along the Western Mediterranean and Atlantic routes. As discussed in detail in Section 4.1, the mortality rate on the journey to the Canary Islands has risen sharply, with an increasing number of boats departing from Senegal, The Gambia, and Mauritania due to the externalisation of European borders, forcing people to take even more dangerous routes.

Fishing boats in a village close to departure points in Senegal. Source: Amélie Janda

This has led to one death for every 3-4 arrivals on the Canary Islands. We fear that the implementation of the PMA will further increase the death toll. It is therefore crucial to thoroughly understand how the new pact will affect the region in order to support those affected in upholding their right to freedom of movement.

2. The PMA – the European Pact on Migration and Asylum

2.1. What is the PMA and what does it say about the EU’s ideas on migration?

The PMA is a set of rules that seeks to define a common migration and asylum system at the level of the EU. Until its adoption by the European Parliament in April 2024, there was no unified document for the management of migration (sometimes called economic or voluntary migration) in the EU. There were rules regarding asylum (sometimes called forced migration, a term that includes both asylum seekers and those persons who have already been recognized as refugees by states). These common rules were defined in the Common European Asylum System (CEAS), which was first created in 1999 and has been modified several times since then.

The PMA creates a broader, more ambitious set of regulations than the CEAS to harmonise all human mobility, although it targets undocumented migration specifically, which it frames in terms of “crises.” Through a number of interconnected regulations, the PMA according to the EU has four official goals:

- To secure the external borders of the EU through screening and identification of people on the move, an update of the Eurodac (European dactyloscopy or fingerprint) database for identifying asylum seekers and undocumented migrants, a mandatory border procedure and the return of those not deemed eligible for protection, and a crisis regulation in emergency situations.

- To improve access to international protection through standardized procedures, including a new Asylum and Migration Management Regulation to be implemented by each individual member state, the harmonisation of standards included in the Reception Conditions Directive, the harmonisation of criteria and entitlements for refugees, and the provision of a set of common rules mandating the cooperation of asylum seekers to prevent (so-called) abuses of the system.

- To create an effective system of (so-called) solidarity and responsibility across EU member states, including a permanent solidarity framework, EU funds earmarked for the implementation of the PMA, clearer rules on responsibilities on the part of member states, and the prevention of mobility of asylum seekers within the EU (they must remain in the country of first arrival until they are given the right to remain or are deported).

- To embed migration in partnerships with countries of origin and transit of people on the move, through the reinforcement of border control capacities in those countries, the criminalisation of human trafficking, cooperation on readmission and returns, and the promotion of (so-called) safe and legal migration pathways.

These may be the official goals, but in reality the main objective of the PMA is to seal the border at any cost.

2.2. Crisis as a mode of governance

Professor Violeta Moreno-Lax argues that crisis has become the dominant mode of governance of human mobility in the EU, and the PMA enshrines this vision of migration as a crisis. This use of the “crisis” framework to manage mobility has several implications. For example, detention is set to become the norm and not the exception when a person’s identity is unclear; treatments that so far were exceptional and illegal (e.g., pushbacks) are likely to become the rule; coercion, deterrence, and containment are the priorities and likely to overrule all other considerations; and human rights will be diluted or negated, along with the legal standards on which they are based. In other words, the veneer of detached crisis management that the PMA provides is an overhaul not just of the EU’s asylum system, but of the entire structure for the protection of human rights in the EU.

One of the reasons for the existence of the pact is the failure of so-called solidarity mechanisms for the sharing of “burdens” (as they are called in EU speech) associated with migration at EU borders, including the expenses associated with the control of the southern border, the provision of SAR (“Search and Rescue”) services, and the provision of legal and other forms of support for asylum seekers and other migrants. So far, southern EU member states (Greece, Italy, Malta, and Spain) have shouldered these responsibilities. Different approaches to encouraging or forcing other member states to step up have, for the most part, failed. Through one of its components (the Asylum and Migration Management Regulation), the PMA eliminates the possibility to opt out and demands that member states choose one of the three following options: to accept to host (relocate) a certain number of people annually, to pay 20,000 euros for each asylum seeker they refuse to relocate (a sort of sanction for not participating in the scheme), or to finance general operational support.

On 12 June, the The Common Implementation Plan for the Pact on Migration and Asylum was adopted by the European Commission. The states have two years from the date of adoption of the PMA by the European Parliament (April 2024) to determine how they will implement these new mandatory rules.

Integrating the PMA into the different legal systems of the EU member states promises to be complicated. We shall expect much confusion as well as conflicts of jurisdiction between EU members, between EU members and southern countries, and even between states and regions, as the recent situation in the Canaries illustrates (cf. Section 3.2). It is not clear how the Member States will implement these new ‘solidarity’ measures between European states, or how Frontex‘s role will evolve. On the other hand, even though the promotion of safe and legal migration pathways is one of the official goals of the PMA, so far there is no evidence this will ever happen. In an article published in the Spanish media Heraldo, Diego Boza, a lawyer specialising in migration and human rights, actually says:

“One of the weak points of the Pact is the absence of proposals for legal immigration channels. It is the lack of safe and legal migration routes that leads to irregular migration.”

The PMA is presented as an improvement of the conditions for people on the move, when actually reinforcing states in their dehumanising and racist practices of punishing people for using their freedom of movement.

3. Spain & the Canary Islands

3.1. Spain

The MED5 group (made up of the Ministers of the Interior and Migration of Spain, Italy, Greece, Malta and Cyprus) met in Gran Canaria on 20 April of that year to discuss the implementation of the new European Pact on Migration and Asylum:

“It is our firm conviction that the key to migration management lies in cooperation, bilaterally and by the EU as a whole, with the countries of origin and transit of migration,”

said Spanish Minister of the Interior Fernando Grande-Marlaska at the press conference following the meeting.

The meeting ended with the adoption of a joint declaration of the five ministers in wich they also called for a budget increase:

“The EU must specify an increase in European funds and flexible financing instruments for cooperation,”

insisted Grande-Marlaska.

The ministers also called for greater involvement of EU agencies in prevention in the countries of origin,

“with special attention to Frontex, which can contribute enormously to the fight at source against the mafias that traffic people and take advantage of the vulnerability and desperation of thousands of people,”

the Spanish minister specified.

Following the adoption of the Pact and faced with an upsurge in arrivals in the Canary Islands, in August 2024, Spanish Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez travelled to Senegal, Mauritania and Gambia to renegotiate bilateral agreements and promote the introduction of very restrictive ‘circular migration’ mechanisms. The details of Pedro Sánchez’s West African tour are described in Section 4.3.

Civil society struggles

While politicians negotiate and give big speeches, migrant groups and allies, migrant rights defender organisations and NGOs have been mobilising. Spanish human rights defenders throughout the country demonstrated against the Pact during the weeks leading up to its adoption by the European Parliament. On 11 April 2024, the day of the vote, a demonstration took place in Madrid. The manifesto “Civil society shouts ‘NO’ to the European pact on migration and asylum” has been signed by 869 individuals and 433 organisations.

Protesters of the “Regularización Ya movement” in front of the Congress of Deputies in Madrid on 9 April. “Regularisation now!” and “PMA kills”, say the banners in Spanish and Catalan. Source: Activists

The implementation of the PMA will trigger the overhaul of domestic and EU-wide migration laws and regulations. It is also likely that the number of detentions and expulsions will increase and that guarantees in asylum procedures will decrease. Compulsory legal assistance throughout the procedure is also under threat. There is a lot of uncertainty about how the Spanish institutions will proceed, but for the moment, Spanish civil society is working on denouncing, observing developments and lobbying.

At the same time, the struggle to regularise the situation of 500,000 people continues and has featured on the Spanish political agenda on several occasions over the last months.

3.2. Canaries

Political clashes over migrant children

In recent months, there have been major political clashes over the reception of migrants in the Canary Islands, particularly over the issue of children on the move. In Spain, the legal system requires that the guardianship of minors who arrive in the country without an adult guardian should fall to the autonomous community (region) where they arrive (see our last regional analysis). The Canary Islands, along with Ceuta and Melilla, are the Spanish regions with the highest numbers of arrivals and are therefore required to house and support more children on the move than other regions. The Canaries are currently in charge of around 5,500 unaccompanied foreign children and youth, a very high number for an archipelago where little money is invested in public infrastructure (schools, hospitals, etc.). For several years now, the Canary Islands government has been calling for solidarity mechanisms to be put in place for regions to participate more fairly in ensuring the rights of children on the move, who are seen as a burden. The Canary Islands government is putting pressure on the other autonomous communities and the central government, led by Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez, to reform the Law on the Rights of Foreigners (ley de extranjería). This would involve amending an article to make it compulsory to allocate children on the move to other regions. On 15 July, the PSOE, Sumar and Coalición Canaria registered the bill in the Congress of Deputies in order to push through this binding distribution of unaccompanied children and adolescents. The proposed reform would require children to be transferred to other Spanish regions within 12 months of their arrival. This would bring some relief to the reception centres in the archipelago when it exceeds 150% capacity. This reform did not go ahead due to the combined opposition of the right and far-right parties PP, Vox and Junts.

This political battle over the protection of children has hardened political discourses in and beyond spaces of political power. Meanwhile, human rights organisations continue to denounce the conditions in which children on the move live and are taken care off.

The PMA in the Canaries

Generally speaking, the PMA has been received positively by the Canary Islands’ political leaders. As a Spanish territory in wich tens of thousands of people are arriving by sea every year, they hope that the implementation of the Pact will relieve them of the so-called ‘migratory pressure’, although they are fairly sceptical about the operational nature of solidarity between EU states. Most official speeches about the Pact merely call for more money and more ‘cooperation projects’ with countries of origin, in the hope of deterring would-be immigrants. The local governement also asks for the presence of Frontex in Canary Islands waters to supposedly ‘save lives’.

One of the main negotiators of the PMA is Juan Fernando López Aguilar, Member of the European Parliament for the Canary Islands, also president of the European Parliament’s Committee on Civil Liberties, Justice and Home Affairs. When the Pact was adopted, he stated that it was designed with the Canary Islands in mind, particularly with regard to the activation of migratory crisis measures:

“The crisis can be declared not only because of saturation at the national level, but also at the local or regional level, with a clause specifically designed for islands such as Greece, Lampedusa and the Canary Islands.”

Since the beginning of the debate on the distribution of children on the move, it is these same notions of compulsory solidarity and crisis that the Canary Islands authorities and central government have been trying to mobilise, but that have been constantly blocked by the opposition (right and far right). In September and October, the political conflict over the reform of the law on foreigners’ rights took a legal turn. The president of the Canary Islands, Fernando Clavijo, introduced a protocol requiring the correct identification of minors and an individual guardianship decision before placing them in youth protection centres. However, the Attorney General’s Office (fiscalía) considered that the protocol was prejudicial to the rights of minors and requested its suspension, which the High Court granted, citing the need to exercise caution and encourage dialogue between institutions ‘to deal with the phenomenon of illegal immigration and its singular impact on the Canary Islands’. Although this report only covers the period between March and August 2024, we wanted to mention these events because we believe that they illustrate the difficulties that the member states will have to face in adapting their legislative systems to the standards of the PMA. The political blockages of this reform of the law on the rights of foreign nationals show the extent to which a compulsory distribution of people on the move will have difficulty taking shape.

Canaries stands against the model of mass tourism and against racism

Over the last six months, the Canarian agenda has been dominated by the systemic crisis in the archipelago and the public protests against the mass tourism-based economical system. Social unrest (precariousness, housing crisis, political corruption, child poverty, etc.) was expressed in the streets on 20 April – the very same day the Mediterranean ministers were having a meeting in Las Palmas de Gran Canaria – by massive demonstrations under the slogan “Canarias tiene un límite” (the Canary Islands have a limit). During these demonstrations, and in the months that followed, the platforms behind the protests also spoke out on the issue of immigration.

Protesters during the 20 April demonstrations in the Canary Islands. Source: Protesters

Some of the placards at the demonstrations carried messages such as ‘The invasion is coming by plane, not by boat’, in reference to the foreign investors who come to build hotels and speculate on property. Other demonstrations took place, this time against immigration. In response, the organizers of the 20 April demonstrations held a rally in Las Palmas on 25 June under the slogan “For anti-racist and anti-colonialist Canary Islands.” In the Canaries, despite an undeniable increase in far-right rhetoric and racist policies, anti-racist voices continue to be raised, demanding that

“public policies guarantee the rights of all our neighbours, regardless of their skin colour, religion or place of origin.”

The organisers demand that the Canarian representatives

“immediately put an end to this political machinery that tortures and murders, and that they stop investing money in tools of control and death at the borders while promoting discourses of fear and threat among the population about resources and security.”

4. The Atlantic Route

4.1. The Atlantic Route in figures

On 28 August 1994, the first boat ever embarked on the Atlantic route: two young Sahrawis arrived on Fuerteventura in a fisherboat, marking the beginning of three decades during which 230,000 people would follow. The route was usually not very frequently travelled (apart from the mid-2000s), but it is now widely known and travelled: Half of all journeys on the Canary Route were made in the past four years, which has severe consequences for the sub-region when we analyse the impact of European migration policies in the South.

Up until 31 August 2024, 25,524 people managed to cross the Atlantic and arrive on the Canary Islands. We welcome everybody who has survived the most dangerous route to Europe – BOZA! (Exclamation used when a border crossing is successful, referring to what motivates people on their migratory journey and keeps them going until they arrive: the thirst for freedom, hope and purpose.) Although arrivals in spring (especially March and April) were rather low, the overall number is much higher than during the previous year, when 11,439 people had arrived by late August. In the past months, the westernmost island of El Hierro has surpassed Gran Canaria as the main island of arrival. By now, around 50% of all travellers arrive on El Hierro. This is largely due to the fact that a greater percentage of boats arrive in the Canaries leaving from Mauritania and Senegal. B., Alarm Phone activist from Laayoune confirms that very few boats are currently leaving from the shores of the Sahara:

“Sometimes you can wait for a whole month without any boat leaving.”

Senegalese fishing boat on shore. Source: Amélie Janda

This general shift to more southern points of departure has also contributed to an even higher death toll. A lot of media attention was given to the boats that arrived in Brazil in April, carrying 20 corpses, with many more probably disappeared at sea, and in the Dominican Republic in August, carrying 14 corpses (out of 77 dead who left Mauritania in January 2024). Yet, deadly shipwrecks also occur in Senegalese, Mauritanian and southern Moroccan/Saharan waters, sometimes not even far from the shores (see Section 6 on shipwrecks). The NGO Caminando Fronteras published statistics according to which 5,054 people had died on the Atlantic Route between January and May 2024. If we put this figure in relation to the 17,327 people who arrived in the Canaries in the same period, this translates to one death per 3-4 people who arrived. This is much higher than in 2023, when approximately one person died for every 6-7 survivors of the Atlantic Route.

4.2. Sahara

The PMA is not yet widely known in the region and there is not yet a direct visible impact of this last round of exacerbating the racist nature of European migration policies. However, European policies of border externalisation have already caused a significant rise in departures from southern Morocco in 2020-2022 and force people to take increasingly dangerous routes. Activists note that European policymakers frequently visit the region, highlighting growing European interest in the region. Since enormous funds are mobilised for the control of so-called irregular migration (we call it the exercise of the freedom of movement), it also has an impact on the socio-economic situation, as A. from Alarm Phone Laayoune explains:

“In the Sahara, resources are mobilised to control migratory flows to the detriment of local development.”

Now departures of people on the move are being pushed even further south onto more perilous routes as repression and surveillance in the Sahara have intensified significantly:

“New surveillance material was bought, such as drones and torches, which are used to spot people on the shores and in the desert. Furthermore, new surveillance posts were built with European funding,”

explain members from Alarm Phone Laayoune. A recent study published in May by Lighthouse and several newspapers sheds light on how surveillance and security equipment financed by European governments is directly used to abuse migrants in the Sahara. Specifically, police vehicles funded by the Spanish development service are used by patrols at the Mauritanian-Saharan border. Several testimonies show the cruel treatment and abuse suffered by Black migrants at the hands of these police patrols. In a second example, survivors explain how dog brigades are used to inflict severe injuries, with the dogs most likely provided by the Austrian government. As Alarm Phone, we believe that these are just a few examples of a large-scale phenomenon: The European externalisation of the border results directly in relentless human rights abuses in the Sahara and the south of Morocco.

Detention centre in Laayoune. Source: Alarm Phone

The nefarious impact of European migration policies is also shown by how Black people are imprisoned in detention centres in the Sahara, without proper trial and respect for basic human rights. Another direct impact is the presence of Frontex staff at the Laayoune airport in order to receive Moroccan nationals who are being deported from Spain.

At the same time, Moroccan authorities try their best to emphasize how efficiently the Moroccan Navy curbs departure attempts. There are regular reports about interceptions off the shores of the Sahara, and the overall number of interceptions this year until September is at 45,015 people who were prevented from making their way to the Canary Islands.

4.3. Senegal & Mauritania

The PMA is little known in the countries of departure

Fishing port in Southern Senegal. Source: Amélie Janda

While Senegalese media has reported minimally on EU policy and agreements regarding migration, the Mauritanian press has reported on the progress of this “reinforced cooperation,” including visits by EU and Spanish representatives, recent immigration bills, working meetings between Mauritanian police forces and the Spanish Guardia Civil, and the opposition’s criticism of recent agreements.

In August 2024, Spanish Prime Minister Pedro Sanchez visited Nouakchott and Dakar on a tour that also took him to neighboring Gambia, with the aim of strengthening bilateral agreements and supporting EU policy. On this occasion, he signed a “memorandum of understanding” with Mauritania’s newly re-elected president, Mohamed Ould Gazouani, similar to the one signed with Senegal in April 2021, with the aim of “combating the mafia” and promoting “safe, orderly and regular migration.”

Details of the implementation of these memoranda are not well known, but the joint declarations suggest that in terms of migration policy, the new regime in Dakar is following in the footsteps of the previous one. Pedro Sanchez praised the “excellent collaboration between Dakar and Madrid.” This includes cooperation with the Guardia Civil on coastal surveillance and facilitating readmission in return for a “circular migration” program that will provide a limited number of work visas and training. This program is used as a smokescreen to justify repressive policies and creates an easily exploitable agricultural labor force useful to Spanish agro-business with minimal gains reported by Senegalese workers. After 145 Senegalese left for Spain under the ‘circular migration’ programme, the Senegalese media published articles on the conditions under which they were working, in breach of Spanish labour law.

Mauritania 2024: a typical example of outsourcing policies

The Mauritanian context of 2024 is a perfect illustration of the cynical way in which the European Union, supported in this case by Spain, is externalizing its borders. European politicians pretend to be moved by the “tragedy of thousands of people who risk their lives in search of a better life” and blame it on the “mafia” and “human trafficking networks,” while promising to promote legal migration routes and “economic opportunities.”

In the “joint declaration on migration” published by Mauritania and the EU on 7 March 2024, they reference various action plans that will be undertaken according to the “respective strategies” of the two signatories “in the field of migration.” This agreement already contains the main axes of the PMA that would be signed a month later.

The EU wants to reinforce Mauritanian detention centers

The section called “Protection and Asylum” includes the goal to “strengthen identification capacities” and “reception capacities […] for asylum seekers in Mauritania,” recalls the PMA initiative to sort out categories of asylum seekers, forcing those unlikely to obtain international protection to remain in a closed center during an accelerated 12-week procedure. This procedure will apply to Senegalese nationals, for whom asylum refusals are almost automatic, as Senegal is considered a politically stable country.

In 2018, when the EU wanted to set up ‘ regional disembarkation centres ’ in the countries of North Africa, they were ultimately opposed by them, which led to the failure of the EU’s plans. Given this precedent, this time the EU institutions need Mauritania’s full cooperation and approval. For now, there are no concrete plans for a detention center to externalize the asylum procedure on Mauritanian soil, but according to a journalist in Mauritania, there is a discussion to create a transit center there with the support of the International Organization for Migration but the Mauritanian government is reportedly against such a center. However, EU funds had already been used to build other detention centres. including the one nicknamed “Guantanamo” built in 2006 in Nouhadibou used to detain migrants stopped along the Mauritanian coast before deporting them. In February 2024, shortly after the visit of the EU delegation, eight Mauritanian police officers went to the Canary Islands for training at the Barranco Seco CATE (Temporary Attention Center for Foreigners). This visit was intended to “inspire” the Mauritanian police force to set up a detention center in the Soueissiya region, 60 km from Nouhadibou, which could house immigrants “before they are deported to their countries of origin.”

A few days earlier, the main opposition parties had declared their opposition to the agreement between the EU and the Mauritanian government concerning ‘the reception and accommodation of refugees refused entry by the EU,’ out of xenophobic fears of a ‘change in the demographic composition of the country’. Only the president of the abolitionist movement IRA, Biram Dah Abeid, did not wish to join the movement, which he said had a racist dimension; he believed that the regime had no intention of providing a dignified welcome for migrants turned away, but simply of pocketing the 210 million euros agreed in the agreement.

The Mauritanian government has denied its intention

And no official statement has been made about the Soueissiya detention center project. How Mauritania’s “reception capacities for asylum-seekers” are to be “strengthened” remains unclear.

Mauritania is adapting its legislation and following in the footsteps of European projects

To “combat […] human trafficking networks,” the EU and Mauritania specified in their declaration of 7 March 2024 that they wanted to “strengthen the capacity of the judicial authorities.” With this in mind, two bills were presented in the Mauritanian parliament on 4 September. The first aims to create specialized courts to deal with cases of “migrant smuggling.” The other aims to introduce a legal framework for “expulsions or bans on entry to the national territory.” This second bill attempts to legitimize entry refusal practices that are already taking place outside legal frameworks and in breach of human rights, international and regional law.

How the EU finances detention and refoulement practices that run counter to the principles of international protection and the right of asylum

Mauritanian policies are already structurally racist against Black people. The Harratin community is significantly underrepresented in the government, and slavery is still practiced. As in other Maghreb countries, the situation is therefore conducive to the mistreatment of people on the move – who are mostly Black – by the Mauritanian authorities.

Last May, a consortium of international media published an investigation documenting “how EU money enables Maghreb countries to expel migrants in the middle of the desert.” Through direct observation and access to non-public documents, these journalists demonstrate that equipment and human resources provided by the EU enable local authorities to carry out violent arrests, confinements, and entry refusals/deportations. According to this investigation, 50 Spanish police officers are on duty between Nouakchott and Nouhadibou, some of them in detention centers, for which 500 million euros are to be allocated by the EU.

In January 2024, a month before European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen visited, journalists observed racially motivated arrests in targeted Nouakchott neighborhoods. Arrested migrants were then locked up in centers such as the Ksar police station. Every week, buses take them to the Malian border, where they are left “destitute.” Toyota Hilux vehicles donated by Spain in 2019 are also used in these operations. Members of UNHCR Mauritania confirm that people with refugee status have been victims of these deportations and sent against their will to Gogui on the border with Mali. In a hypocritical and cynical move, the EU responded to journalists’ solicitations by asserting that respect for human rights and the right to non-refoulement were fundamental principles of migration management.

Increased surveillance at sea continues to push people on the move to take greater risks.

According to the same investigation, in 2023 nearly 3,700 interceptions at sea were carried out by joint patrols with the Guardia Civil in Mauritanian waters (according to a Spanish Ministry of the Interior count).

The Senegalese Navy’s collaboration with the spanish Guardia Civil and Frontex is well established, and more and more pirogues are being intercepted off the Senegalese coast. In addition to these collaborations, in 2022 Frontex received the green light to explore a project to send armed agents to monitor migration in Africa, with Senegal as the first destination. The campaign 72h Push Back Frontex, led by the Boza Fii organisation, has been protesting every year since 2021 against the deployment of Frontex in Senegal.

In May 2024, the Senegalese Navy intercepted 554 people on pirogues, compared with 269 between December 2023 and April 2024. Since 2023, the Senegalese Navy has further increased its surveillance and control capabilities, with the delivery of six aircraft by Spain “to detect the departure of migrant boats bound for the Canary Islands” and the purchase of three offshore patrol boats from the French Piriou Group. The Guardia Civil use planes and boats for surveillance, and although the Senegalese government has told the UN Human Rights Council that they only keep watch and do not take part in interceptions, testimonies indicate that they intercept, detain and then return people to the Senegalese authorities. The boats of people on the move must then take riskier routes to avoid these

patrols.

In contrast to the promises of visas, forced returns

Over the past few months, a Senegalese association supporting people on the move has noted abusive expulsions of Senegalese nationals living in Germany. An AP member tells us:

“On 3 September 2024, 8 Senegalese nationals, including a mentally ill woman, landed at Dakar’s Blaise Diagne international airport. Accompanied by around thirty German police officers, they arrived empty-handed. Some of them claimed to have received a sum of 50 euros, others not, as they already had money on them. One of the deportees testified that two police officers came to his home on the morning of 26 August at around 7am, to take him to a center pending his deportation. Just as he was getting ready to go to work, they entered his house without any supporting documents or reason for deportation.

The same applies to a Senegalese man who was deported on 9 October 2024. Unlike his predecessor, he was arrested at his workplace, then taken to a center where he spent 15 days before being deported, after spending 20 years in Germany. Another man deported from Germany who was in asylum proceedings confides that his deportation procedure was initiated by the person managing his file. After applying for a work permit, which was subsequently refused, he received threats from the same official who handled his files and ended up initiating his deportation procedure.

They share similar experiences of forced return, and you can read on their faces despair, contempt and sadness with the feeling of having to start all over again from scratch.”

As regards Mauritania, B., a local Alarm Phone activist, tells us he has no knowledge of any expulsions made this year. In their joint declarations, however, the EU and Mauritania recall “their commitments under the Samoa agreements” and indicate their intention to strengthen cooperation on return and readmission, or in other words to facilitate deportations and migrant repression.

What can we expect in the future?

Over the past 20 years, numerous agreements have been signed between Senegal, Mauritania and EU countries, such as the Accord Relatif à la Gestion Concertée des Flux Migratoires (Agreement on the Concerted Management of Migration Flows) signed between Senegal and France in 2006. The UTF, the Emergency Trust Fund for Africa, negotiated in 2015, also includes numerous budgets allocated to combating so-called irregular immigration. In all, hundreds of millions of euros have been injected into Senegal and Mauritania for this purpose.

The 7 March agreement, signed in Mauritania, is accompanied by a budget of 210 million euros between now and the end of 2024. This is a striking increase on the 80 million euros received from the EU since 2015. Several sources refer to a total budget of 500 million euros if we consider the subsidiary funds for infrastructure projects.

At a time when neighboring countries of Mali, Niger, and Burkina Faso are questioning partnerships with some EU countries on migration and in other domains, this reinforced cooperation means more and more money for repressive policies that flout human rights conventions, though government language tries to hide this murderous reality. To understand their concrete applications and the effects they will have, we need to monitor these agreements.

Under the positive heading of “Team Europe,” the agreements signed with the EU include collaboration with Frontex, Europol and the European Union Asylum Agency (EUAA). With the PMA, the EU is deepening its method, with the stated aim of processing people on the move as far away from the continent as possible, to carry out accelerated, de-individualized asylum application procedures, and to facilitate expulsion, even for children, via closed transit centers, to be able to rapidly expel those whose asylum applications are rejected.

If the mauritanian government consents to those agreeements, it raises the question of whether, in the future, Mauritania will receive these rejected asylum seekers, independently of their country of origin, so that they can then be deported. Thousands of people are already being detained each year in Mauritania in very poor conditions, and the construction of new prisons with EU funding (“detention centers”) is underway. Once again, the border regime implemented by states reinforces the carceral regime punishing people on the move who continue to fight and use their freedom of movement!

5. Morocco

“While the PMA is a new reform, it is clear that what it entails is merely a continuation of previous measures to curb immigration that were set in motion when Frontex was created,”

say activists from Alarm Phone Morocco.

“Morocco is known to have some of the harshest guards at the border between Europe and Africa. The measures introduced by the PMA had already been in place for some time, both at borders and in transit countries such as Morocco.”

The signing of a new agreement on migration and asylum between Morocco and the EU has been announced since March 2024. It is difficult to find completely independent media outlets on this matter, as according to activists local media is highly filtered, controlled and approved by the Moroccan state, which is in turn financed by the EU. The official Moroccan discourse boasts of migratory flows management that respects human rights compared with other Mediterranean countries:

“(…), although Morocco is one of the main migration routes to Europe, it remains the safest and most secure route. Rescues at sea by the Moroccan coastguard are almost a daily occurrence, which is not the case on the other side of the Mediterranean, where migrants are abandoned to their fate or redirected to countries such as Libya.”

The question of EU recognition of Moroccan sovereignty over Western Sahara appears to remain a major issue if Morocco is to agree to play the role of “Europe’s policeman” that the country has always denied.

While the official line is to refuse to bend to the EU’s wishes and to retain its sovereignty over the management of its borders, the reality on the ground is very different: Arbitrary and racist arrests continue on a massive scale, even of people with regularised immigration statuses. These atrocities are even further enhanced by the PMA, as activists explain in the following sections.

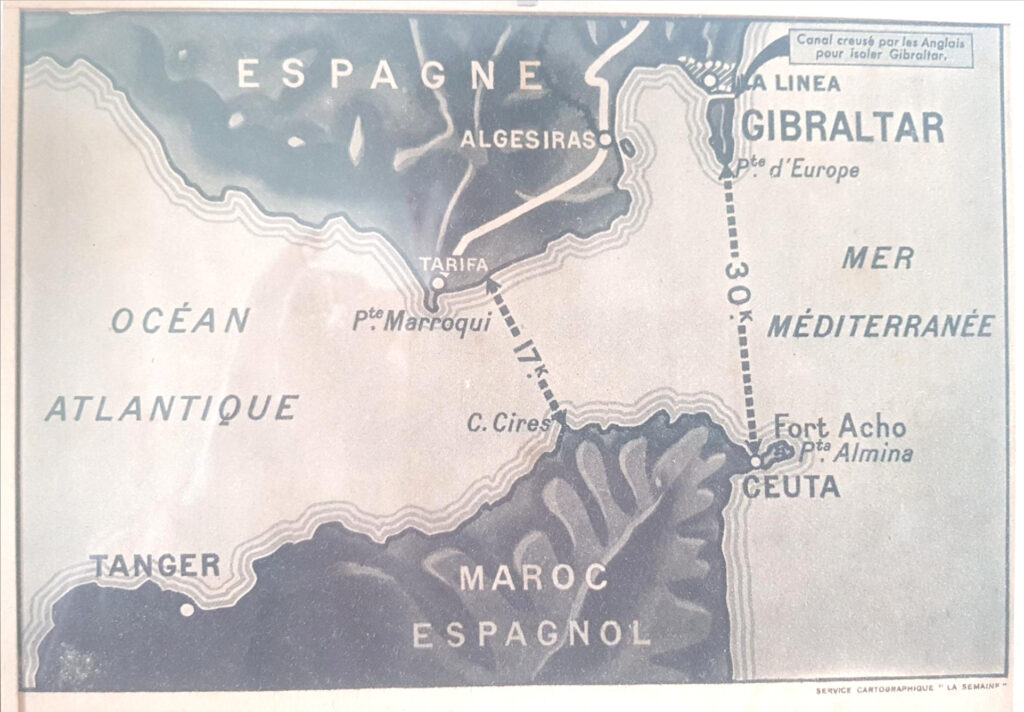

5.1. Tangier, Ceuta & Street of Gibraltar

As the PMA introduces measures that restrict freedom of movement, the rights to international protection and asylum are also being limited. In Morocco, ‘migrants’ are generally seen as a threat while asylum seekers, on the other hand, are seen as potential refugees. For example, there is easy justification to arrest someone who does not have regular papers because they can be quickly deported back to their country of origin. But in accordance with international law, in Moroccan migration law, asylum seekers are more protected than migrants, making it more difficult for the Moroccan authorities to arrest asylum seekers, even if their application is still in progress. However, in practice, Moroccan authorities often disregard the formal asylum process. In cases of arbitrary arrest, the intervention of UNHCR lawyers is sometimes required to secure the release of asylum seekers. In recent months, activists in Tangier have seen many asylum applications rejected, and some denied processing altogether.

The EU & Morocco share a long history – of borders. Source: Alarm Phone

On the other hand, the EU’s intention to externalise its borders is all the more visible since many associations financed by the EU are encouraging people on the move to stay in Morocco. Even the Moroccan government has designed regularisation campaigns, and it is now far easier to get residency permits in Morocco for people from West/Central Africa.

Activists in Tangier are reporting daily difficulties for people entering the city. There are police on every bus and train asking for papers (residence permits) from any Black African wishing to travel to Tangier. Activists recently witnessed the case of a young Guinean who left Rabat and jumped off the train for fear of being caught by the police at Tangier-Ville station, incurring serious injuries. On the coast, too, there are radars, drones and other devices to detect movements along the beaches, making it practically impossible to land a sub-Saharan convoy in Tangier. These implementations aim to satisfy the EU and help limit the arrival of people in Europe by reinforcing measures at the borders. Controls are much tighter for Black people, as evidenced by the observation that almost all the boats returning from Spain to Tangier had only Maghrebians on board.

The PMA will probably also have implications for the criminalisation of Alarm Phone’s work, as it becomes harder to communicate what the network does in a way that could not be construed as illegal. It is also harder for Alarm Phone to coordinate rescue for people in distress at sea. With the new measures that continue to strengthen the borders and reduce the number of people heading out to sea, it is possible there will be fewer and fewer cases of assistance. Moreover, as a result of heightened restrictions on migration, activists in Tangier have seen lots of people signing up for voluntary return and abandoning their plans to travel to Europe.

The operation of the Moroccan coastguard and the spanish Salvamento Marítimo (SM) has also been affected over the years by EU migration policies. Salvamento Marítimo is a civilian organisation, unlike the Moroccan coastguard, which is a military organisation. The area where the civilian organisation can carry out search and rescue has been reduced in order to extend the territory of the military organisation. This is evidenced by reports that since 2018 activists have not seen SM boats crossing to Morocco.

There have also been new players and forms of cooperation in the securitisation of the border. Auxillary forces were recently deployed in response to recent attempts by groups of people to cross the barrier into Ceuta. We have seen an escalation of the number of security forces, financed through EU agreements with Morocco.

This new pact reinforces the shortcomings that existed in the previous pacts to limit migration. As governments have toughened things up, this runs counter to the fight against borders by networks like Alarm Phone. Therefore, as activists, we must know how to communicate effectively in order to avoid being criminalised. Nevertheless, as one Alarm Phone activist said:

“If we have solidarity between us and good communication and empathy, I think we can never be criminalised. And the work will continue to the ends of the earth.”

5.2. Nador & Melilla

In Nador, the implementation of the PMA simply reinforces oppressive laws and measures that have already been in place for a long time. The main result expected is a further strengthening of border controls. This is already manifested by an increased presence of Moroccan security forces in border areas, particularly around the Melilla barrier. Controls are intensified not only along the land border, but also in coastal areas to prevent attempted sea crossings (see: Nador section of our last report). On the legal level, restrictions regarding the right to asylum are nothing new. “Opportunities to obtain international protection are extremely limited for irregular migrants,” comments A., AP Nador member, on that topic. “The asylum process remains opaque and difficult to access, especially for people on the move who often do not have access to legal information or specialized lawyers.” (For further reading on legalization challenges in Morocco see our Alarm Phone Analysis from 12/2023.)

“Solidarity networks in the Nador region, while having limited resources, continue to resist the repressive measures put in place under the PMA. These networks include local human rights associations. I fear further harmful consequences for the rights of migrants in the Nador region. The strengthening of border controls, the criminalization of migrants, and the restriction of access to asylum constitute major challenges that local communities and solidarity networks must face on a daily basis.” Says A.

News from the Nador region

Migration via the Alboran route continues, nearly exclusively by Moroccan citizens and for a price of up to the huge amount of 12,000 € per person. After starting in Nador and Dariush, the use of so-called “phantom boats” to transport people on the move expands to the Al-Hassima coasts. AMDH (Human Rights organization in Morroco) Nador suspects that there are actually various interests at stake to not completely thwart the launching of speedboats towards Spain:

“There are two main aims behind this traffic of Moroccan nationals:

– political: to empty Morocco and the Rif of these young people in order to deflate the social crisis. Remember that this forced migration of young Moroccans increased considerably after July 2017, the date of the repression of the Rif Hirak.

– financial and rentier: after sub-Saharan migration was chasied from north to south, the Nador and Driouch coasts are now completely reserved for this paid migration of Moroccans. Huge sums of money are at stake.[…]” (Source : AMDH Facebook post from 1 June 2024).

Official figures estimates that there are around 500 minors currently (mid-July 2024) in Nador, in precarious conditions, that are attempting to leave the country towards EU. And the number seems to be on the rise.

“The deepening economic and social crisis, the collapse of the education and health system, and the political exploitation of the right to immigration, mobility, and the total closure of the eastern and northern borders are pushing more minors and young people to look for all the ways to leave the country […],”

The situation of the unaccompanied minors, also called “harraga,” is extremely difficult (see also our last report). The authorities don’t do much to alleviate their situation. AMDH even reported in July the discovery that a center in Arouit/Nador province that had been financed by the EU to shelter unaccompanied minors had been – very cynically – transformed into barracks for police officers.

24 June

24 June was again a day filled with anger, pain and sorrow as we commemorate the so-called Melilla massacre, where dozens of people were murdered at the Melilla fences by the authorities in 2022 (see also reports from Alarm Phone or Caminando Fronteras). We – and many others, the UN committee against torture, political parties, human rights organizations, relatives of the victims – are still calling for an independent investigation of the events that led to the death of at least 37 people, mainly of Sudanese origin. The total number of victims is not clear; at least 70 people remain missing in the aftermath of 24 June. But instead of supporting an independent investigation, the head of the Guardia Civil in Melilla, Arturo Ortega Navas, has defended the actions of this security force during the jump of 24 June. Ortega Navas has even asserted that, in the event of a similar event, the authorities wouldn’t act any differently.

Many bodies have been buried without identification after the massacre, and relatives are still in the dark about the fate of their missing loved ones. Recently, AMDH Nador was able to receive the information that in the weeks before the anniversary of 24 June, around 51 bodies, presumably victims of the massacre, were buried silently in the cemetery of Sidi Salem/Nador, after being kept in the morgue for 2 years along with many others (see: AMDH report).

Cemetery of Sidi Salem. Source: AMDH Nador

“The photo of the migrants’ square at the Nador cemetery which summarizes one of the main rules of Moroccan migration policy: a single grave bearing an identity and suitably constructed in the middle of several dozen precarious graves bearing no identity. This rule is: Identify as few dead or killed migrants as possible and bury them in precarious graves without names or nationalities so that they disappear in just a few years. In this way, those responsible for these policies believe they can erase all their violations against migrants, mainly the number of deaths.” (Source: AMDH Nador)

Many people who were detained during the massacre on 24 June were convicted and are still incarcerated. But not only the criminalization of people on the move and so-called trafficking networks is ever ongoing, also individual flight helpers are harshly prosecuted. In April, the Spanish Prosecutor’s office requested seven years in prison for a 44-year-old man of Moroccan nationality and a 60-year-old Portuguese national, who had attempted to hide two undocumented Moroccan citizens between the front wheels of a bus, next to electrical circuits, while travelling on a ferry to Motril across the Alboran sea.

But the question remains, who are actually the real criminals, with border guards using violence un-prosecuted, not only at the fences, but also at sea. On 22 August, a shocking video was shared on social media, showing a Guardia Civil speedboat blocking a small boat of 4 people on the move towards Melilla, and eventually ramming their much bigger boat against and on top of the smaller vessel used by the migrants. It is a miracle that all passengers survived, although according to AMDH Nador’s sources they were incarcerated in Morocco.

Guardia Civil endangers boat of people trying to flee to Melilla. Source: AMDH Nador

6. Shipwrecks & missing people

On 12 April, four dead bodies are found in a boat adrift off Cartagena, Spain.

On 13 April, nine dead bodies are found by Brazilian fishermen off the coast of Pará, in northern Brazil. Authorities believe that the boat, probably en route to the Canary Islands, had set off from the Mauritanian coast. It could have carried at least 25 people.

On 16 April, a dead body is found on the beach of Águilas, Spain.

On 29 April, an oil tanker sights a boat about 110 km from the island of El Hierro (Canary Islands). Nine survivors are rescued. There were 51 of them as they left M’Bour (Senegal) around 17 April. 42 people lost their lives.

On 6 May, a dead body is washed ashore on the coast of La Gomera (Canary Islands). On 7 and 11 April, two more dead bodies were found on the shores of the same island. The experts in marine currents of the University of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria report that it is unlikely that these are the victims of the shipwreck rescued on 29 April south of El Hierro. These people probably lost their lives in another shipwreck.

On 9 May, Alarm Phone is informed that a boat is intercepted by the Mauritanian authorities. Two people lost their lives at sea and one person fainted after arrival. They report having been left alone and without any support or care.

On 3 June, a young man drowns off Nador, failing to reach the boat that was supposed to take him to the Spanish peninsula.

On 4 June, a dead body is found on the beach of Ceuta. The person supposedly tried to swim into the city, as he was wearing a wetsuit and fins.

On 5 June, Alarm Phone reports on a missing boat with 130-150 people that left from Nouachott, Mauretania a week earlier.

On the same day, (2),(3) a boat is rescued south of El Hierro (Canary Islands). They had left from Nouakchott (Mauritania) on 25-26 May. The number of deaths is estimated between 12 and 50. An unidentified person dies after being transferred to hospital.

On 19 June, a boat is found 800 km from the Canary Islands by a commercial vessel. According to the media the boat left on 30 May from Mauretania with ~150 people on board. At least six people are dead; almost 80 people are still missing.

On 23 June, a boat with 47 people on board arrives on El Hierro, Canary Islands, Spain. The health service assists the people and confirmes the death of one of them.

On 1 July, at least 14 and up to more than 30 people die in a shipwreck close to the coast of Senegal. Several people remain missing.

On 1 July, as Alarm Phone reports, a shipwreck occurs in the Atlantic. A boat carrying 167 people from Senegal sinks off the coast of Mauritania. The authorities are reporting more than 50 people missing.

On 2 July, three people remain missing in a search and rescue operation close to Cabo de la Nao, Spain.

On 4 July, at least 87 people die in a shipwreck off the Mauritanian coast. Only 36 people survive the tragedy; several people remain missing.

On 5 July, Alarm Phone reports on a boat with 63 travellers that left Nouakchott on 24 June. The search is still ongoing, but the boat is missing.

On 6 July, a boat with 55 people arrives on El Hierro, Canary Islands, Spain. One person is found dead.

On 7 July, a boat with 151 people on board arrives in the Canary Islands. One person didn’t survive the crossing.

On 8 July, a dead body is found on the beach of Ceuta. It’s believed that the person died while trying to swim from Morocco to Ceuta.

On 10 July, another dead body is found on the Ceutan beach.

On 11 July, a boat with 79 people on board is rescued close to Tenerifa. One person is found dead.

On 16 July, two people die in hospital after their arrival in the Canary Islands. The boat with 51 people on board had left Senegal one week before.

On 20 July, two boats with ~130 people on board are rescued close to the island of Lanzarote. Two people didn’t survive the crossing.

On 20 July, 196 people are rescued when their boat sinks ~160 km from Dakhla. Among the people the authorities find one deceased person.

On 20 July, Alarm Phone is contacted by a boat with 64 travellers in distress off Western Sahara. The boat is adrift and taking in water. Alarm Phone mourns the loss of two people who lost their life in the Atlantic.

On 21 July, a dead body is found on a beach close to Almería, Spain.

On 6 August, a boat appears in the Dominican Republic with 14 lifeless bodies. Six and a half months earlier, 77 people had departed from Mauritania.

On 7 August, a dead body is found on the beach of Ceuta. The person was wearing a neoprene suit, which indicates that he may have tried to swim to Ceuta.

On 11 August, a boat carrying 68 people is intercepted 16 km southwest of Dakhla. Two bodies are found dead.

On 12 August, Alarm Phone reports that two people have perished off Dakhla, while trying to reach Spain in a boat carrying 75 people.

On 13 August, Alarm Phone is informed by relatives about a missing boat carrying 59 people that departed from Laayoune heading to the Canary Islands.

On 14 August, a dead body is found on the beach of Ceuta.

On 15 August, three young people are reported missing in the media after they attempted to swim to Ceuta the night before.

On 15 August, a dead body is found close to Agadir, Morocco.

On 19 August, Alarm Phone is contacted by relatives searching for a missing boat that departed on 6 August with a group of 11 people from Mostaganem, Algeria heading to Cartagena, Spain. 11 days later, their fate remains unclear.

On 30 August, Alarm Phone reports that a boat with 12 people from Mostaganem, Algeria capsizes near the shores of Cartagena, Spain. 10 people can be rescued, but two people are missing.

CommemorAction in memory of all those who died or disappeared due to the border regime. Source: Amélie Janda

***

Disclaimer on our terminology

Alarm Phone is a network of volunteer activists. The bulk of Alarm Phone members in the Western Med and Atlantic region are West African or European in origin. As a consequence, we are much more embedded within the communities of people on the move from West African countries than we are from the Harraga communities of the Maghreb. This inevitably leads to underrepresentation of the experiences of the latter group. The only way to rectify this problem is to expand what we do and work to build a truly transnational community of resistance. This is slow and laborious work, but we are committed to doing it.

The language that we use is important. The words that we use also carry the weight of their history, and that is a history of power. We constantly struggle to view the world correctly and to find the right descripition of what we see. There is no single viewpoint that will encompass everything. To see the world correctly, we need a kaleidoscopic view. This report is a collective endeavour. Many of the authors are not writing in their first language, and most of the witness testimony is also given in a second or third language. We consider this a strength. We do not wish to regiment the language used in our descriptions of people and their backgrounds. Where someone might baulk at ‘sub-Saharan’ as implying inferiority and prefer ‘Black’ or ‘Black African’, another might reject the racialisation implicit in the latter terms. Equally, some of us avoid talking of ‘migrants’ and prefer to emphasize personhood with ‘people on the move’, but for others of us this language is fussy and unnatural and we are proud to be migrants. We have left, as much as possible, the authors’ different choices of description, especially where the author is herself a person on the move.