Tahíche Prison, Lanzarote, Canary Islands. Source: AP Canarias

1. Introduction

All along their migration paths, people on the move are confronted with many forms of violence by states and their representatives. The border regime, which forces people to travel along increasingly dangerous and sometimes deadly routes, works hand in hand with the incarceration regime.

Having already written a report on the criminalisation of people on the move some time ago, we wanted to participate in the movement that attempts to make visible the places used by states to hide the repression they exert on those who defy border regimes on a daily basis. Writing about incarceration, in the context of our work at Alarm Phone, is an integral part of our fight for freedom of movement for all. Prisons, and all other places which detain people, are part of a continuum of violence which we condemn. Borders, prisons, and other places of detention all form part of a racist, sexist, homophobic, ableist, and classist system of population control by states. In our fight for a world free from institutional violence, we must denounce all forms of incarceration and detention, including of people on the move and their allies. All of these places, from prisons to humanitarian camps, reproduce and participate in the global system of racial, social and economic apartheid that relies on the criminalisation of the people whom authorities wish to exclude from society, particularly racialised, migrating, trans and non-binary people, the poor and sex workers. We stand in solidarity with all prisoners, political or otherwise, who suffer violence at the hands of this carceral and punitive system.

In this report, we wish to address the violence associated with all forms of detention, in prison, in police custody, in humanitarian camps as well as in detention centres. These closed-off spaces are constantly being built and expanded in all the countries of the Western Mediterranean and Atlantic region. These enclosed spaces halt people’s journeys, either spontaneously or for long periods of time. As a tool of migration control, incarceration serves both to punish people on the move who have defied border regimes by exercising their freedom of movement, and to segregate and render invisible those who are considered undesirable in national territories. In addition to the violence of detention, which is described by the various authors writing in the following paragraphs, and the racism manifested in the policy and practice of arrest, incarceration and deportation, there is also the violence of absence, and that of being rendered invisible. As many members of Alarm Phone express, the first and foremost question is finding out who is locked up, where, and how the person feels. What are their needs? Do they need clothes, money, medication, books or any other object? Do they want to contact friends or family? Beyond the staggering numbers of people detained, it is a question of recreating a link between places of detention and the outside. A vital link which is often the only means of accessing the bare minimum (clothes, money for the canteen or to call their family, legal support, etc.).

Numerous criminal laws have been adopted, mainly since the 2000s, in order to imprison more and more and for longer periods of time – and particularly people on the move. Specifically, the laws to combat so-called people smugglers have led to the incarceration of thousands of people in Morocco, Spain, Senegal, Algeria, and Mauritania. In Spain and Morocco, for example, and particularly in the Canary Islands, a practice carried out by the authorities has now become widespread with the support of Frontex: Two people are arbitrarily arrested from each boat that arrives on the coast. Made the scapegoats of the violence of states’ border regime, these people risk up to several decades in prison. In Mauritania, as in Senegal, new detention centres for foreigners are being built: depriving people of their freedom and punishing them before deporting them. In Morocco, arbitrary arrests and roundups are a regular occurrence: People are arrested, sometimes locked up and forcibly moved to the south of the country and the Sahara. In Algeria, people on the move are arbitrarily taken back across the border to Niger or Mali and abandoned in the desert, endangering their lives.

In the face of all this violence, solidarity and resistance is being built and constantly strengthened. Every day, the members of Alarm Phone and our allies try to identify those who are imprisoned and detained and provide them with support, using the means available: from collecting clothes to seeking alternative legal support. With this report, we reaffirm our support for all those who suffer the violence of states’ border and prison regimes and continue the fight for freedom of movement for all!

2. Sea crossings and statistics

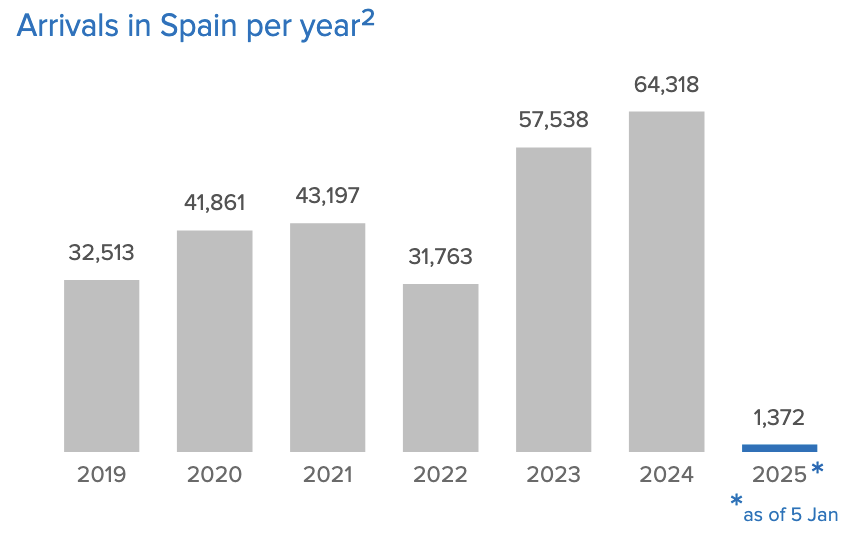

In 2024, Alarm Phone handled 146 cases along the Western Mediterranean and Atlantic routes, assisting at least 6,425 people on board these boats. According to UNHCR, 64,318 people arrived in Spain that year, meaning Alarm Phone supported approximately 10% of those who reached the country.

Figure 1: Arrivals in the Spanish state per year. Source: UNHCR SPAIN Weekly snapshot – Week 1 (30 Dec 2024 – 5 Jan 2025)

Between September 2024 and the end of February 2025, Alarm Phone handled 117 cases in the region, involving at least 5,932 people. Of these, 76 boats took the Atlantic route, 20 boats crossed the Alboran Sea, 40 boats departed from Algeria and one distress call came from the Strait of Gibraltar. During this period, 38 boats were rescued by Salvamento Marítimo, 19 boats arrived by themselves, 3 boats returned to shore, 11 boats were intercepted and 1 boat was rescued by a merchant vessel. However, the number of incidents in the Mediterranean and Atlantic regions remains alarmingly high. In the period of this analysis, 33 cases remain unclear and at least 6 shipwrecks occurred. This means at least 399 people have experienced shipwrecks, while the fate of 1,665 people remains unknown. We are aware of at least 154 missing persons, 135 survivors, and 76 confirmed deaths during the winter of 2024/2025.

Most of these tragedies happened on the most frequented route, the way across the Atlantic. It was – again – a record year of arrivals. 46,843 people made it to the Canary Islands – we welcome each and every one of them! This is not only significantly more than the 40,330 people in 2023 but also the highest number of all time. It is particularly noteworthy that arrivals can now peak at nearly any month of the year. The months with many departures due to favourable meteorological conditions are usually September to November; however, January and February of 2025 (as well as January and February of 2024) show that arrival numbers can also be very high in other months. The Salvamento Marítimo workers’ union CGT speaks of a “de-seasoning”, meaning crossings are not linked to certain seasons anymore. Yet, 2024 is also a record year of death. As the data from the NGO Caminando Fronteras show, 9,757 people died on the Atlantic route in 2024, the majority of deaths occurring between Mauritania and the Canary Islands. Unsurprisingly, this makes the Atlantic Route the most lethal crossing that we know of.

In every month we witnessed some devastating shipwreck. We mourn all the victims of the border regime and demand an end to the killing at sea. While we provide a more detailed list of the incidents in chapter 4, we want to highlight a few examples here to give a better picture of the extent/scale of these tragedies: Between 2 and 3 September, several boats that left from various points along the Algerian coast disappeared for several days. For some of them, there is no evidence of their arrival, so we fear that they are invisible shipwrecks and that their passengers have died tragically and have not been found or identified among the hundreds of corpses arriving on the coasts of Spain and Algeria every day. On 20 October 2024, another case from Senegal (Saloum/Djifèreon) saw 160-180 people reported missing. Alerts were sent to Mauritanian authorities, but there is no further information on their fate. (Source: Alarm Phone). On 26 November, eleven people left northern Morocco, attempting to reach Europe. While two survivors arrived in Almería, the fate of the remaining nine people is unknown. Our solidarity and thoughts go out to their families, who continue to wait for news. (Source: Alarm Phone). December was particularly deadly along the Atlantic and Algerian routes. A shipwreck resulted in bodies washing up on Algerian shores. In another distressing case, 18 people who left Tipaza, Algeria, on 29 December remain missing, despite authorities being informed. (Source: Alarm Phone). And the new year has begun just as tragically: On 2 January, a wooden boat that had departed from Nouakchott, carrying around 85-90 people, shipwrecked. Some survivors were found, and Alarm Phone is in contact with their relatives, trying to confirm names. (Source: Alarm Phone). Throughout the month of January, we received almost daily reports of bodies washed up on Algerian shores. Sometimes a dignified burial means a lot to the families of the people that went missing in the sea, and unfortunately, many of these bodies remain unidentified (Alarm Phone reported).

While the Atlantic route remains by far the most dangerous and most frequently chosen, Alarm Phone is being informed more and more about the tragedies occuring on the journey from Algeria. In the last months, several families have contacted Alarm Phone to report that they had lost contact with their loved ones who had departed on a boat from Algeria to Spain, either to the Balearic Islands or to some point on the Spanish mainland coast such as Alicante, Murcia or Almería. Many of the people come from Algeria, but we are aware of some people taking this route having started their journey from other places such as Somalia, Mali, Burkina Faso or Benin. Whether these developments can be interpreted to mean that there are more departures from Algeria or simply that more people in this region know about Alarm Phone and have built up enough trust to contact us cannot be determined with certainty.

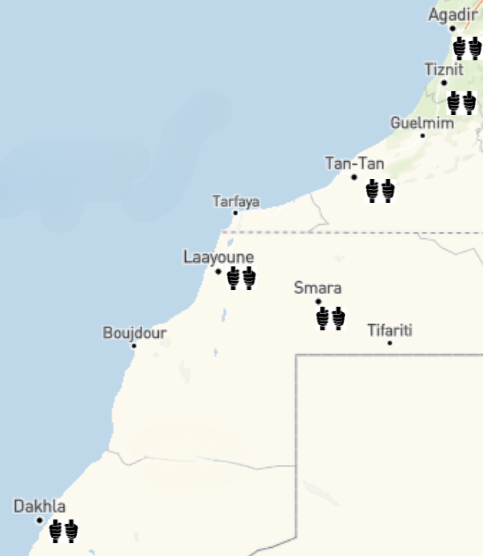

The case is quite different when it comes to developments in the south of Morocco and in the Sahara, as members of Alarm Phone working there have reported that the places of departure have somewhat shifted. Due to the intense policing, daily harrassment and military deployments in the Sahara, many people looking for a crossing have now moved to Agadir. This is also mirrored in where departures take place: Since September 2024, only 2 out of 48 Alarm Phone cases in the Sahara and southern Morocco left from around Boujdour; all the others left from the Tarfaya, Tan-Tan and Guelmim areas. One of those notable exceptions was a horrible shipwreck of a boat that departed on 22 September 2024, with only 4 out of 60/61 people surviving. (Source: Alarm Phone). According to this shift in departures, the Canarian island of Lanzarote started receiving more people again, while previously most arrivals were in the westernmost island of El Hierro (due to many departures from Mauritania and Senegal).

3. Incarceration in the different countries of the WM

3.1. Morocco

In general, Morocco has an incarceration rate that is somewhat similar to its neighbouring countries in the North of Africa. Yet, two developments have caused NGOs and human rights defenders to raise the alarm: first of all, incarceration rates have grown in the past years, and secondly, a rather large percentage of prisoners (45%) is untried, meaning they are in prison awaiting trial. Furthermore, Morocco is under criticism for prison overcrowding, despite its 77 facilities all over the country and in the Sahara. According to the annual report published in November 2024 by the Moroccan Prison Observatory (OMP), these prisons run at an estimated 159% capacity, meaning that every detainee has only 1.75 square meters at their disposal. In addition, the report finds severe shortcomings when it comes to hygiene, the quality of food, and general facilities. Together with other civil society actors, the OMP calls for alternatives to incarceration. However, activists and journalists denouncing the injustice of incarceration often face heavy repression from authorities for this kind of work. Activists, journalists and others risk incarceration themselves.

According to official statistics from late 2023, only 1.5% of all prisoners are of foreign nationality. Out of those, 77% are African nationals, which would amount to roughly 1100 prisoners from African countries. Given that already the Laayoune prison has a very large group of West and Central African inmates (as AP members from Laayoune confirm), this can hardly be true. People on the move are incarcerated for a variety of reasons:

The 02-03 immigration act from 2003 stipulates that people on the move without a valid residence permit can receive several months of prison (Art. 42) or be held in custody before being deported (Art. 50). The law also contains provisions on the facilitation or organisation of migration, also punishable by several years of prison (Art. 52). Since its promulgation, the 02-03 immigration act has been severely criticised by activists since it criminalises people who exercise their right to freedom of movement. Harsh prison sentences are also provided by the 27-14 human trafficking act from 2016. Depending on the severity of the “crime”, prison sentences range from 5 to 10 years or even to a lifelong sentence.

As the different subchapters (3.1.1, 3.1.2, 3.1.3) show, people on the move are subjected to racist treatment in Moroccan prisons. Their basic needs (clothing, hygiene) are not sufficiently met, and they receive disproportionately harsh sentences due to a lack of legal council and interpreting.

In late 2022, Morocco’s General Delegation for Prison Administration and Reintegration already announced a 2022-2026 strategy for implementing better detention conditions (including e.g. better health care and psychological support) and enhancing social reintegration measures for prisoners. Given the dire problems outlined in the OMP 2024 report, there is an extensive need for action. However, if Morocco (like all other countries in the Western Med region) keeps imprisoning people for trumped-up charges, petty crimes and the mere exercise of their freedom of movement, we have serious doubts that building more prisons or installing better showers is going to change anything at all when it comes to the incarceration of people on the move.

3.1.1. North

In the Tanger region, people on the move are the frequent target of arbitrary arrests and pushbacks, following which they may be displaced to towns far from the border. Among these arrests and pushbacks, some people are detained on suspicion of offences related to illegal migration and given longer prison sentences if they are implicated in more serious crimes, such as organising convoys or drug smuggling. These charges are often made if people are caught with materials for preparing a departure or trying to climb the barrier at Ceuta, for example if found with life jackets, motor fuel or hooks for climbing the fence. Police will often also search phones for video or photo evidence of organising boat or drug and alcohol smuggling.

It is difficult to ascertain the precise number of departures from Tanger towards Spain since there is very high securitisation of the border and frequent arrests have reduced departures considerably, making it practically impossible for people on the move to launch a boat. Therefore, people are being forced to attempt the extremely dangerous Atlantic routes further south. Nevertheless, when boats are intercepted in the north, the police will search for 2-3 people to detain and accuse of being the ‘captain’, the smuggler or responsible for organising the voyage, in an attempt to scapegoat individuals for the violence of the border. This is hugely arbitrary and does not involve an investigation, for example the ‘captain’ suspect is often merely the person closest to the engine.

According to procedure, people are detained for a maximum of three days before they see a prosecutor who determines their charge; then they may be detained in a local prison before trial for an indeterminate period of time, which can be many months. There are four known prisons in and around Tanger: the old prison complex on the Mesnana/Boukhalef road was closed and replaced by a new prison opened in 2024, Tanger locale 2 prison, as part of the ongoing prison reform by the DGAPR. There are two more prisons in Hjar Nhal and one in Asilah. In the Tétouan prison, which is also awaiting new facilities, claims of mistreatment were raised last year, but denied by the authorities.

The old Tanger prison had been overcrowded and dilapidated for years. It was finally replaced by new facilities in 2024. Source: AP

In Tanger, Black people routinely face discrimination from the police and justice system, like elsewhere in Morocco. Mostly, prisoners are detained for organising journeys or driving boats, less for charges involving their legal residence status. Activists have heard testimonies of deplorable conditions in Tanger local 2 prison. As one activist described, ‘once you are found guilty of a crime you are no longer considered human’. There are reports of severe overcrowding, very limited space with sometimes as many as 60-70 people inhabiting each cell, and inadequate food. For people on the move, prison is very isolating as non-Moroccan nationals are often unable to receive visits or stay in touch with their families because of the prohibitive cost of telephone top-ups. As a result, many people leave prison with very poor mental and physical health. An activist in AP Tanger recently met a Guinean woman who was completely malnourished after being incarcerated. In January, there were also reports of measles outbreaks in Tanger locale 2 prison, further exemplifying the poor conditions inside prisons.

3.1.2. East

There is a high number of Moroccan-national unaccompanied children that arrive in Nador province without parents or relatives with the intention to cross to the Spanish peninsula. Lately, also groups consisting of underage girls, the youngest around 12 years old, were spotted among these so-called ‘harraga’. The local authorities frequently confine, if not to say incarcerate, these minors in the “Centre de Sauvegarde de l’Enfant” in Nador city under the pretext of protection (see also our report on conditions for minors in the Nador region). There is no access to appropriate educational or psychological programs; the minors are isolated from support networks and outside contacts. Material conditions are precarious; the diet is insufficient and unbalanced.

Foreign adult citizens are taken into custody for offences related to their migratory status (irregular entry, no residence permit, attempted border crossings). They are being locked up in informal detention centers, like the infamous Arekmane detention center in a village east of Nador city, or in police stations, awaiting deportations further away from the border zone. The Arekmane center is a former socio-educational centre but has been requisitioned by the authorities to lock up people on the move arrested near the coast. Not even the National Human Rights Council (CNDH) has access to it. (See also our previous report “The hidden battlefield” from 2019.)

Foreign nationals who are sentenced for border-related offences are being held in Nador prison. People are tried e.g. for accusations of ‘trafficking’, for supposedly organising ‘attacks’ on the border fences and in previous years also for being assumed captains, but sea crossings by foreign nationals are currently very rare. Arrests and accusations remain highly arbitrary. Sentences are harsh – just in November 2024, 14 foreign nationals who had been detained at the fence between Nador and Melilla were sentenced to 10 years in prison. “The conditions in prisons are deplorable” reports C., activist on the ground, who tries to channel support to the detainees.

“Officials overcrowed cells with up to 2 inmates per place, managers refuse to provide hygiene kits and clothing to migrant detainees, and food is of poor quality. There are reports of discrimination by managers against Black detainees by limiting their access to medical care and activities. There are also reports of violence and abuse of vulnerable prisoners. The authorities refuse to protect the rights of incarcerated migrants.”

There are reports of hunger strikes for better conditions, and apart from solidarity among the detainees, who often share their limited ressources, the communities and activists try to render support in any possible way. There are also independent organisations like AMDH Nador and GADEM who observe and monitor detention conditions, document human right violations and follow trials against people on the move in court.

3.1.3. South

Location of prisons in the South of Morocco and the Sahara. Source: AP

In the South of Morocco and the Sahara, there are several large prisons where people on the move are being held: Dakhla, Laayoune, Smara (east of Laayoune), Bouizakarne (north of Guelmim), Tan-Tan and Aït Melloul (Agadir). In accordance with the new prison strategy adopted by Morrocan authorities (see the introduction), “reinsertion measures” are emphasized (e.g. in the Dakhla prison), for instance professional training for detainees. In addition, a new prison was opened in Laayoune in 2023, on the northern outskirts of the town. The notorious “Carcel Negra” (“Black Prison”) in the centre of Laayoune had been vastly overcrowded for years, with terrible living conditions. With the new prison, the living conditions have somewhat improved for the regular inmates; however, for people on the move, living and hygienic conditions remain intolerable. Since a lot of daily necessities (food, clothing, toileteries) are provided by family members or associations, people from countries such as Mali, Senegal and Ivory Coast are cut of from support. Instead, they have to rely on the little that local associations supporting people on the move can provide. AP Laayoune explains:

“Sometimes, there are prisoners who have only one piece of clothing that they live with for months without being able to change. That’s why associations sometimes call for donations. But these prisoners can only be visited by family members, and they are in the country of origin and thus do not have the financial means to come and help them. Sometimes, members of the consulates or certain associations are also granted access to the prisons, but that’s not always the case.”

Family members from other countries such as Senegal have already started self-organising to support their loved ones in prison; however, this work is incredibly difficult due to the lack of information and assistance from authorities.

Since criminalisation against people on the move is so prevalent, a large percentage of prisons in the South and Sahara is by now filled with people from West and Central Africa. The AP team in Laayoune explains how this process of criminalisation works:

“Hundreds of people are accused of being boat drivers or having organised illegalised crossings. They are prosecuted by the Moroccan criminal system in order to deter migration. They are accused of being smugglers, captains or responsible for navigation on a boat. Moroccan authorities never respect their right to an interpreter for the judicial proceedings. Sometimes, people are beaten so that they will divulge who was the captain. Often, people are accused without any proof just because whenever a boat is intercepted, the authorities need to find two or three people to arrest as ‘responsible’. The other boat passengers are sent to a detention centre for one or two weeks, before they are taken elsewhere in Morocco. Those accused of being the captain are taken to the police station and then to prison, where they wait for the trial for a period of two to four months. The judgement itself is completely arbitrary, and there is no defence lawyer; sometimes people are condemned by a judge on a video call. The sentences are absurd, mostly from 5 to 10 years of prison, sometimes even 15 years. When the accused is able to afford a lawyer, they can receive a prison sentence of 3 months to 3 years only. Sometimes families are able to provide funds for a lawyer, but that’s not often the case.”

3.2. Incarceration in Mauritania

Introduction

‘The country has become bogged down in the role of zealous guardian of a world order as absurd as a mirage.’ ELY Moustapha

In 2024, Mauritania was the main country of departure for boats bound for the Canary Islands (54% of the 658 vessels that arrived in 2024). Since 2021, the EU has strengthened its collaboration with Mauritania through a joint operational partnership (JOP), with a budget of 4.55 million euros. This project aims ‘to support the fight against migrant smuggling and the management of irregular migration in Mauritania’.

In this context, there has been an evolution in the legislative framework and in the means of depriving people on the move of their freedom.

Legislation

In 2020, the Mauritanian legislative had already adopted two important laws: law no. 2020/017 on the prevention and repression of human trafficking and the protection of victims and law no. 2020/018 on the fight against the smuggling of people on the move. Under European pressure, two new bills were drafted and came into force on 9 November 2024.

The first (no. 2024/038) provides a legal framework for ‘the refusal of entry or the expulsion from the national territory of illegal aliens’. It aims to provide a framework for deprivations of freedom that are already taking place, such as ‘removal to the border’, which are in reality racist roundups in the neighbourhoods where Black people live and work. During the first eight months of 2024, 10,753 migrants were deported.

The law provides for sentences of up to 2 years in prison for anyone who counterfeits documents or is in possession of falsified documents (including false visas) and up to 6 months in prison for anyone who enters Mauritania without passing through official crossing points. Law No. 2024/038 also makes it possible to incriminate ‘any foreigners whose presence or activity may cause a disturbance of public order’ as well as persons who ‘assist’ them.

To apply this manifestly xenophobic law, a second law allows for the creation of a specialised court in the wilaya of western Nouakchott. On 17 February, the Mauritanian Prime Minister reaffirmed before this new court: ‘Slavery, migrant smuggling and human trafficking are serious crimes that must be combated because they constitute a serious threat to the security and stability of the country.’

The arrests

People on the move are arrested at sea (by the coastguard) or on land during raids on their homes in suburban neighbourhoods (e.g. in Nouadhibou: Kairane, Tcharka, Numero, etc.). The operations are carried out by joint teams of the Mauritanian police and the Spanish Guardia Civil, and the individuals are then handed over to the National Security Department (emigration service).

Members of AP Mauritania tell us:

‘During their custody, an investigation is carried out to identify those responsible: smugglers or captains. Once identified, they are placed in detention centres pending trial. If they are found guilty, their sentences vary from 2 to 5 years, with a fine of up to 500,000 Ouguiya and confiscation of property, which will be transferred to the public treasury. The others will be placed in the ‘temporary holding centre’ pending their deportation. 111 people on the move, including 28 women, are currently in prison [in Nouadhibou], and 76 people have not yet been tried. The charges are diverse: trafficking, theft, smugglers, captains, etc.’

Detention conditions

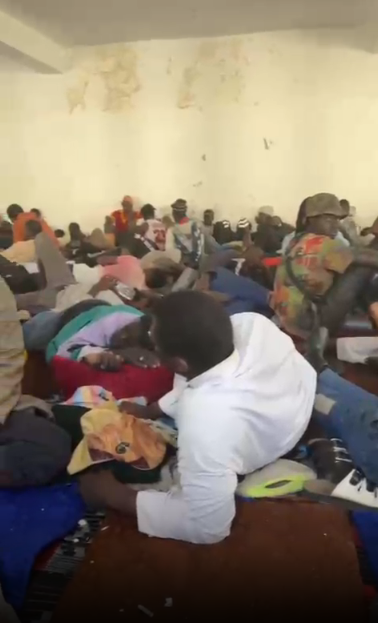

More than a hundred people from Senegal detained in Nouakchott after being intercepted at sea in early March 2025. Source: Screenshot of a video filmed by one of the detainees

The current ‘temporary holding centres’ are old buildings repurposed for the detention of people on the move. Like detention centres in general, they are overcrowded and the living conditions are deplorable.

AP Mauritania reports:

‘[In Nouadhibou] there is a former school that has been used as a temporary reception centre that can accommodate up to 300 people and sometimes up to 500 people or more. The centre aims to prepare people on the move for their return (deportation) through border posts so that they can return to their countries of origin, and their stay in the centre can last from 6 months to 1 year.’

‘In the detention centres, most of the detainees complain about the hygiene conditions; the food and the access to healthcare are deplorable.’

Within the framework of the POC, the European Trust Fund has financed the rehabilitation works of two centres (Nouakchott and Nouadhibou) for a budget of 500,000 euros. This is a smokescreen: Fortress Europe claims to be comporting itself with ‘dignity’ and boasts of the provision of ‘separate dormitories for men and women, kitchens and refectories, hygiene and sports areas and meeting spaces’. A total of 118 places are planned between these two new ‘Complexes Humanitaire d’Accueil Temporaire’ (CHAT) [Temporary Reception Humanitarian Complexes].

With regard to the administration of justice, migrant detainees testify to the lack of means to obtain a lawyer who takes a serious interest in their cases and are the victims of the search for an ideal culprit. Trials are often rushed and, although law no. 2020/017 provides for the right to receive information about the proceedings in a language that one understands and the right to use an interpreter duly authorised by the authorities, translation is not provided. This is evidence of the racist dimension of the Mauritanian administration, which communicates only in Arabic or Moorish, even though a large part of the population speaks other languages.

Human rights are also violated by the slowness of the procedures, which can last more than a year without a trial. This leads to arbitrary detention and non-compliance with Articles 65 (free care and treatment), 66 (social assistance) and 67 (right to legal aid) of law no. 2020/017.

The fight against the imprisonment of people on the move is carried out solely by international, national and local activists and NGOs (they protest against the slowness of procedures and against the arbitrary detention of people on the move). Due to a lack of resources, the ICRC (International Committee of the Red Cross) closed its offices in Nouakchott in 2023.

3.3. Incarceration in Senegal

Introduction

Under pressure from the European Union, Senegal (like Mauritania) has taken it upon itself to criminalise migration, often resulting in human rights violations for those imprisoned for the ‘crime’ of movement and travel.

The legislation

In Senegal, Law 2005-06 of 10 May 2005 on the fight against human trafficking and similar practices and for the protection of victims is a reference point for migration policy. Although there have been calls from civil society to amend and replace this law, and it is said to be under review, this legislation is still the main legal basis for the detention of people on the move, with the DNLT (the Division for Combating Trafficking of Migrants and Similar Practices, created in 2018) helping to enforce it.

In addition to targeting human trafficking, this law criminalises movement by also punishing ‘organised clandestine migration’ with 5 to 10 years of imprisonment and a substantial fine when Senegal is used as a point of departure, transit or destination (Article 4). Although the law specifies that ‘victims’ cannot be targeted, it does not specify what constitutes ‘organising clandestine migration’. Article 4 therefore allows the state to imprison foreigners and citizens who contribute in any way, even indirectly, to the departure of boats. The vagueness of the law has been used to criminalise irregular migration (and not just its organisation). The 2005 law has given greater scope for abuse by the police, whose work is poorly supervised, by introducing into Senegalese procedure the possibility for the police to enter homes in the middle of the night, leading to abuse and violation of privacy.

Trials and prison conditions

According to a study carried out by Senghane Senghor (a lawyer and human rights activist) and his collaborators, under the direction of La Cimade (the study is currently being finalised), people imprisoned under this law for migration-related offences are victims of major violations of human rights and Senegalese law. These violations include excessively long detention periods (up to 8 days), people sent to prison without having seen a prosecutor, people detained even if they have not actually done anything (accused of planning a trip), and a lack of transparency of the charges. Foreigners in prison (mainly from neighbouring countries such as Mali, Guinea and the Gambia) are particularly vulnerable to these violations, having little chance of due process under Senegalese law, as they may not be able to communicate or to have access to an interpreter if necessary. But Senegalese people (who make up the vast majority of detainees) are also victims. If detainees do not have the means to hire their own lawyer, they often never meet their court-appointed lawyer before their court appearance. Processing times are very slow: For misdemeanour cases, the time limit is 6 months, but for criminal cases, the length of the investigation is not limited, and researchers have found people who have spent years in detention without being tried.

As there is no budget to feed people in police custody, investigations are often rushed so that detainees can be transferred to prison as quickly as possible (or released). Senghor and his team found that many of those imprisoned were ‘mere passengers’ for whom there was no evidence that they had anything to do with the organisation of the journey – they were often vulnerable people who had no access to representation or information. For example, they found a case in Saint-Louis of a young person who was detained in 2023 for organising a trip because he had been handed a compass when he was arrested. There were also cases of rights violations when the Senegalese police pursued people they thought were preparing to leave (the report includes accounts of midnight searches of family homes and possibly illegal seizures, with the police taking all the money they could find on the premises). Often, people do not know exactly what they are being accused of.

An Alarm Phone Dakar activist talks about his summons and subsequent detention in police custody:

‘I was summoned to the police station, I didn’t know the reason and they refused to give one. Then I realised that they just wanted to get hold of me because they said I knew about the people who wanted to leave and I didn’t report them. I explained that it wasn’t my role to report them, but they insisted and held me for 36 hours, confiscating my phone. When I realised I was going to spend the night in police custody, I asked a friend to send me some food because they hadn’t given me anything to eat or drink all day, nor to anyone else held there. I was cold in the cell, and they refused to let me bring my jumper or my boubou [tunic and trousers]. The next day, I saw the prosecutor, and following this hearing, as there was no evidence to charge me, I was released.’

For us, this detention is an indication that the Senegalese government, after meeting with the Spanish and EU authorities, is seeking to further criminalise solidarity around migration.

Criminalisation can go very far, with harmful effects: Senghor’s team found two women imprisoned for several months in 2024 even though they had nothing to do with migration. One woman spent several months in prison before being released after being accused of providing meals to a group of people preparing to leave without her knowledge, and another has now been in prison for 9 months awaiting the outcome of her trial for housing a pirogue [boat] engine in her yard that allegedly belonged to a trip organiser whose existence she was also unaware of.

Conditions in Senegalese prisons are very poor. According to a 2020 report, detainees suffer from prison overcrowding (‘218 people in a 70m² room’, according to an Amnesty International report), insufficient food with little nutritional value, and deplorable hygiene conditions. Activists imprisoned in Senegal in 2023 have also testified to the deplorable conditions, including beatings, deprivation of food for 48 hours, and women imprisoned with their babies in these conditions.

Resistance and solidarity

There are many calls from civil society to reform the law, procedures and conditions in prisons. Mandiogou Ndiaye, public prosecutor at the Court of Appeal and member of the Constitutional Council, published a critical study of the 2005 law with Nelly Robin, showing how this law is being used as a weapon in the externalisation of European borders. Civil society organisations such as the Ligue Sénégalaise des Droits de L’Homme [Human Rights League of Senegal], Article 19, and RADDHO (Rencontre Africaine pour la Défense des Droits de l’Homme [African Convergence for the Defence of Human Rights]) have also protested against the illegal detention, especially the imprisonment that undermined the freedom of expression of political prisoners under Macky Sall’s regime (such as the activist Alioune Sané and several opposition figures, including the current President of Senegal, Bassirou Diomaye Faye).

Former detainees have also fought against poor conditions and human rights violations, but due to repression under Macky Sall, some went into exile, like Ibrahima Sall, president of the Association pour le Soutien et la Réinsertion Sociale des Détenus (ASRED) [Organisation for the Support and Social Reintegration of Prisoners]. In January 2025, the prisoners’ cause received more media coverage, with Moustapha Diakhaté, a politician, protesting against the ineffective lawyers and poor conditions in Reubeuss prison on his release, following his conviction for abusive language in November 2024. Nonetheless, the movements led by political prisoners do not shed light on the conditions of detention of foreigners in Senegal. People on the move in senegalese prisons remain, unfortunately, still quite invisible to the public eyes.

Conclusion

Given their first-hand knowledge of prison conditions, the current regime in Senegal would seem to offer an opportunity to reduce violations of prisoners’ rights (even if conditions are improving, these places of confinement remain tools of state violence). We often hear that the 2005 law is already being revised. But with the externalisation of borders and pressure from the European Union, Senegalese President Bassirou Diomaye Faye has for the moment opted to reinforce the same ‘coercive’ policy as his predecessors by criminalising people on the move instead of denouncing the real source of his problems: European migration policy, which pushes people to take increasingly risky journeys.

3.4. Algeria

Introduction

In Algeria, people on the move do not automatically end up in prison. Foreigners and nationals are only imprisoned when they are accused of having committed a criminal offence, regardless of their administrative status in the country (irregularised or regularised under Algerian law).

The country does not impose heavy sanctions (in the form of prison sentences) on the presence of foreign persons in migration, regardless of the type of migration, settlement, transit or even departure. Nevertheless, other forms of violence are present, notably the roundups and collective expulsions of Black people to the desert.

In the past, human rights defenders and trade unionists have denounced violations of migrants’ rights in general. Currently, however, the situation in Algeria is extremely dangerous for human rights activists and trade unionists who demand rights, including defenders of migrants’ rights, making it difficult to disseminate open campaigns in support of people on the move.

Acts of resistance nevertheless emerge from time to time. We recall the first raid on people on the move from West/Central Africa on 2 December 2016, during the night of their departure, in the Zéralda leisure centre in the suburbs of Algiers, set up to collect the arrested Black people before their deportation to the desert, a protest movement occured. The people on the move refused to get on the buses without knowing why they had been arrested or their destination, and without collecting their belongings. The response to this protest was batons and tear gas.

Punishing assistance to the illegalised exit of people on the move

In 2003, Algeria ratified the Palermo Protocol against the smuggling of people on the move by land, air and sea, criminalising the means by which people on the move can cross borders. In 2009, when the criminal code was amended, the definition of the terminology ‘illicit trafficking of migrants’ was completely skewed in relation to the UN definition and the one contained in the Algerian decree ratifying the Protocol.

Article 303 bis 30 of the Penal Code considers as ‘illicit trafficking of migrants’ the act of organising an illegal departure from the national territory of a person, directly targeting departures to Europe and attempts to cross the Mediterranean by people on the move, whether foreign or Algerian. Contrary to the UN Protocol, which is itself highly questionable, it is not assistance for entry that is condemned, but exit, as part of a logic of coercion and criminalisation of attempts to move north.

Furthermore, non-Algerian nationals have been turned back or deported from European countries to Algeria, depending on whether Algeria issues them with a laissez-passer. Once they arrive at Algerian airports, the individuals are taken to police stations where they can be held for more than a year before being deported or released.

Punishing the illegalised exit of Algerians

In the case of an Algerian citizen attempting to migrate (irregular exit from the country), they are not generally subject to a custodial sentence, unless they are also convicted of another criminal offence. An offence may be, for example, falsifying a travel document, or being designated by the state as an ‘actor in the smuggling of migrants’, i.e. having participated in facilitating a departure or journey.

Punishing people on the move by pushing them back into the desert

Many foreigners are arrested and detained pending deportation or removal to the border following an ID check or a tip-off from a neighbour.

The authorities then use two practices. In some cases, the individuals are placed in police custody until they are brought before the public prosecutor and given suspended prison sentences for being in the country illegally. Foreigners in an irregular administrative situation, such as many Moroccan migrant workers, are often taken to waiting or detention centres until their embassies issue the travel documents necessary for their deportation.

In other cases, the authorities also rely on a system of collective deportations and removals to the desert of people in an irregular situation (mainly for Black people and/or people with ‘dark skin’). Sometimes people are held in police stations or gendarmerie stations. In other cases, if the city has so-called waiting centres intended for accommodation (in other words places allowing detention), people are being detained there pending deportation or removal to the border. Indeed, Law 08-11 has a significant punitive chapter (Chapter 7) relating to deportation and removal to the border, which the authorities use largely against people on the move of sub-Saharan origin in an irregular administrative situation.

Discriminatory treatment is observed with regard to foreigners in an irregular administrative situation. For some nationals, detention lasts for the time it takes to obtain the laissez-passer issued by their consulates, and once the travel documents have been obtained, their deportation to the border is organised with the assistance of the authorities of their home countries. For other people on the move, the detention lasts only a few hours, the time it takes for the general roundup that began that day or the day before to end, and the time it takes to put them on the coaches, without trying to find out the identity of the people, and without notifying the diplomatic representatives of their countries. Arrested people on the move from West and Central Africa are treated like cattle.

Since 2 December 2016, the deportation of Black people to the border (with Mali and Niger) has become the Algerian authorities’ main method of managing migration.

These are therefore mainly expeditious and collective deportations: The people are then abandoned in the desert, at the mercy of the elements and without any official help. This situation, denounced daily by the comrades of Alarm Phone Sahara, endangers the physical and mental integrity, and too often the life, of people on the move in the Sahel. As they explain, these expulsions are often part of a chain of violence suffered by people on the move wishing to cross the Mediterranean Sea:

‘On the one hand, the Algerian security forces regularly carry out raids and mass arrests in migrants’ places of work and residence, including construction sites and empty buildings. At the same time, since 2023 there has been an increase in chain deportations, during which people are deported to Tunisia (often after being pulled back at sea), to the Algerian border, and then by the Algerian security forces to the Nigerian border.’

Conditions of detention

In prisons, Black migrant people, once sentenced, are held in a separate cell and are not mixed with national prisoners. However, during the period of preventive detention, for example while detention orders are in force, or even before the final judgement, the prisoners are placed in the same cell, and each awaits their trial.

Even though Algeria has started building new prisons and large-scale detention facilities, the current prisons, especially those from the colonial period, are overcrowded, largely because pre-trial detention has become the norm.

Prisons in Algeria are closely monitored in terms of hygiene and the spread of diseases specific to the prison environment. Prisoners have rights in this area. With regard to food, there is a lot to be done in this area. The food in detention centres is meagre. It is the families of the prisoners who provide food parcels, and currently, they are only delivered twice a month.

Foreigners and even nationals who have no family receive absolutely no help from the outside. Detainees are not allowed visits from people who have no family ties. In fact, the law only allows visits from first- and second-degree family members. Furthermore, it also happens that people are detained in a detention centre for indefinite periods, in violation of Algerian law and the renewable 30 days it provides for.

On the other hand, in the Oran Detention Centre, created in 2024, the accommodation and hygiene conditions are more favourable. Nevertheless, while people on the move are entitled to make phone calls, they are not allowed visits from acquaintances or friends. As for visits from family members of the 1st or 2nd degree of kinship, we do not yet know whether this is possible for foreigners.

These places remain places of incarceration used to punish people who have exercised their freedom of movement and confronted the border regime.

3.5. Incarceration in Spain, focus on the Canary Islands

In Spain, there are three types of facility where people on the move are deprived of their liberty: CATEs, CIEs and prisons. CATEs (Centros de Acogida Temporal para Extranjeros, places where people on the move are held in police custody from the moment they arrive in Spain for a maximum of 72 hours) and CIEs (Centros de Internamiento para Extranjeros, detention centres where people are held pending their forced return for a maximum of 60 days) are specially designed for foreign nationals who have entered the country illegally or who are in an irregular administrative situation. People on the move accused of having committed an offence can go to prison, either in pre-trial detention pending their trial, or once the trial has taken place and they are found guilty and sentenced to a prison term of more than two years.

Misuse of anti-human trafficking legislation

The Spanish judicial system criminalises people on the move who arrive in Spain. They can be imprisoned as soon as they arrive and detained for several years, due to misuse of anti-trafficking legislation (Article 318 bis of the Criminal Code).

A database compiled by Canary Islands lawyer Daniel Arencibia synthesises information from more than 1,000 judgments handed down between 2018 and 2024 throughout Spain concerning alleged boat ‘captains’. The analysis reveals prosecution protocols with numerous violations of fundamental rights. The study also reveals that, for the same charges, the public prosecutor’s office in the Canary Islands, the region with the highest number of arrivals, requests heavier sentences than in the other regions (autonomous communities) of Spain. Moreover, in the Canary Islands, Malian citizens have been convicted, even though the Geneva Convention is supposed to protect people who cross the border to flee a country at war from any criminal sanction (Article 31.1). Similarly, the Canary Islands are the only Spanish region where minors have been imprisoned for being the captain of a boat. The conviction rate in the Canary Islands is 93% of those accused of having participated in the organisation of the trip.

The criminalisation of captains in the Canaries

In the Canary Islands, there are five prisons spread over four islands: one on Tenerife, two on Gran Canaria, one on Lanzarote and one on Las Palmas. According to police sources, in 2024, 110 people were charged and convicted for ‘encouraging illegal immigration’ to the Canaries. The police aim to charge at least two people per boat, although there have been cases where up to eight people have been charged for the same boat. Depending on the island of arrival and the resources available to the law enforcement authorities, the procedures can be very different, which reinforces their arbitrary and opportunistic nature.

When a person is accused of being the captain or of having taken part in organising the voyage, they are remanded in custody as a precautionary measure (medida cautelar). Spanish law provides for pre-trial detention if there is a risk of absconding, concealing or destroying evidence, or if the offence is repeated. However, the people accused of being captains are systematically placed in pre-trial detention, without these criteria being checked before adopting such heavy-handed precautionary measures. According to data gathered by Arencibia, the average length of pre-trial detention in the Canary Islands is 295 days in Las Palmas and 395 days in Santa Cruz de Tenerife.

The Process of eliciting accusations

During supposedly voluntary interviews with travellers, the police and Frontex exert pressure in order to obtain ‘accusations’ against other travellers. These ‘interviews’ take place in the CATEs, when people have just disembarked, are extremely weak and disorientated and are being held in custody in the CATEs. The procedure takes place without a lawyer or qualified interpreter. A report entitled ‘Violation of human rights in the Canaries in 2024’, produced by the organisations Irídia and Novact, condemns misleading deal-making on the part of the authorities:

“Among the advantages offered, there is the regularisation of the administrative situation and the condition of ‘protected witness’. However, (…) these two proposals are often ineffective.”

According to lawyer Loueila Sid Ahmed Ndiaye, another way of exerting pressure is to tell the person that if they don’t accuse anyone, they run the risk of being accused by others. The accused (almost always a man) is often convicted solely on the basis of one or two statements from anonymous ‘protected witnesses’, which is contrary to the case law of the European Court of Human Rights, echoed by the Spanish Supreme Court. In addition, the evidence is often dubious or obtained when the mobile phone is confiscated without the express consent of the accused or his or her lawyer.

Recently, a new procedure was detected in the Las Raíces camp on Tenerife. People on the move, most of whom have arrived on the island of El Hierro, are generally first placed in this macro-camp of military tents (which host hundreds of people), pending their transfer to other humanitarian centres on the Spanish mainland. Several witnesses (camp workers, lawyers) claim that the police are asking the Ministry of Inclusion (which is also responsible for migration) to suspend the transfers until the police investigation to identify the captain has been completed. People from the same boat are housed in the same tent for several weeks, or even months, in an atmosphere of permanent tension due to the pressure of having to name someone in order to unblock this situation of disguised deprivation of liberty.

The judicial process

At the start of the legal proceedings, the public prosecutor asks for 8 years’ imprisonment, but generally offers a reduced sentence if the accused pleads guilty (known as “conformidad”), in which case he or she waives the right to a trial and the evaluation of evidence. This offer from the public prosecutor is usually made after several months or years of pre-trial detention. Most defendants, nearly 80% according to Arencibia’s analysis, accept the conformidad. This is due, on the one hand, to the difficulties in accessing an adequate defence. Most defendants have court-appointed lawyers who are unfamiliar with immigration procedures and laws and who do not have sufficient resources to study and analyse cases individually. Defendants may also decide to plead guilty because of the psychological damage caused by their long stay in pre-trial detention. In a media inquiry published in December 2023 in the Spanish medium Contexto y Acción (and in many other media across Europe), the lawyer Loueila Sid Ahmed Ndiaye, who has already defended several captains on the Canary Islands, explains:

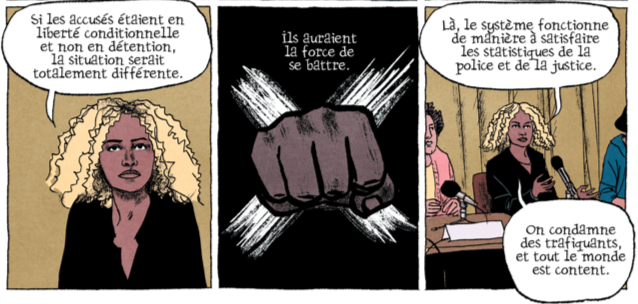

“It’s an extremely unfair procedure […] Pretrial detention is a psychological weapon. If the accused were on probation and not in detention, the situation would be completely different. They would have the strength to fight back. But here, the system is designed to satisfy the statistics of the police and the justice system. We arrest and sentence traffickers and everybody is happy.” (see comic below)

Extract from the comic “Passeurs malgré eux” [“involuntary smugglers”], an inquiry by Fabien Perrier, Taina Tervonen and Jeff Pourquié. [For translation, see text above] Source: La Revue Dessinée #47, spring 2025.

“the deplorable role of the criminal courtrooms of the provincial courts, which make “a very racist interpretation of a judicial procedure”, and state that “They wouldn’t do it with people from here, no rights are guaranteed, only xenophobia”.

Furthermore, if they are convicted, once their sentence is over, these people cannot regularise their administrative situation in Spain because of their criminal record (if the conviction is for 3 years, they will have a criminal record for 5 years). Most of them are subject to administrative removal procedures and find themselves blocked from gaining access to legal residence rights for many years.

A method of migration control

Using the so-called ‘fight against mafias and human trafficking’ to criminalise people trying to reach Europe has become a migration control measure, particularly in the Canary Islands. Since sentences of less than two years are suspended and do not result in imprisonment, the Canary Islands public prosecutor’s office (unlike other autonomous communities in Spain) systematically requests at least three years. These sentences are seen as ‘setting an example’, based on the belief that they could deter other would-be travellers. In addition, this produces statistical data that enables the Spanish state to demonstrate that it is fighting the so-called mafias. This was acknowledged by the public prosecutor of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Teseida García García, in an interview conducted as part of a journalistic investigation, in which she stated that if the convictions did not carry a prison sentence:

‘The message to Spanish society and also to the countries of origin would be that they get away with it. The convictions are a reminder that there are risks involved in this journey’.

Throughout 2024 in Spain, there were further journalists’ investigations highlighting violations of the specific rights of captains, such as this investigation (in French). Recently, however, there has been a certain change in the discourse on captains. Press releases issued by the police or the Superior Court of Justice bring to public attention proceedings in which the captain or captains are allegedly guilty of murder. Choosing to publicise and exploit these cases in order to portray the captains not as smugglers but as murderers could be seen as a police and judicial counter-offensive to recent criticism of their practices.

Prison conditions

Y. is a Senegalese citizen serving a sentence in Tahíche prison in Lanzarote for having been at the helm of the zodiac that brought him to the Canary Islands from the Moroccan coast with 53 other people. He is currently in ‘tercer grado penitenciario’, which means that he is allowed to spend a few days a month outside prison. He shares his cell with another inmate, and each cell has a bathroom. As far as living conditions in prison are concerned, the most difficult thing for Y. was the isolation and not being allowed to contact his family. ‘For the first two years, I didn’t have a mobile phone to talk to my family.’ He also says that conditions are worse for those who have no money:

‘Those who have no family or anyone here, if they behave well, receive about €20 or €30 every six months on a sort of payment card. In principle, this is to be able to buy food, tobacco or things like that. I prefer to use them in the phone box to talk to my family. But it goes quickly. And if you haven’t got any money, you’ve got nothing because everything is more expensive than on the outside.’

It is possible to work in prison, but the wages are very low. ‘I got between €150 and €200 for working 8 hours a day in the kitchen for several months.’ According to Y., the worst thing about prison is the treatment by the guards. ‘There are some good people, but most are bad, very bad… and racist.’ In the months leading up to his trial, which took place on the island of Gran Canaria, he was transferred from Lanzarote prison to Las Palmas prison. He says that conditions there were much worse: more prisoners per cell, communal showers, poorer quality food, etc. Above all, he remembers: ‘I heard an official there say, directly to our faces, that she didn’t like Black people. She told us that we smelled bad.’

Resistance and solidarity

In the Canary Islands, there are a number of actions of solidarity and resistance to the criminalisation of captains. Alongside lawyers who are committed to defending captains or who have worked to collect and systematise data, such as Daniel Arencibia, there are organisations and groups that visit and support imprisoned people: on the island of Lanzarote, the Derecho y Justicia organisation, on the island of Tenerife, the Assembly in Support of Migrants, and on the island of Gran Canaria, the Pastoral de Migraciones and the Federation of African Associations of the Canary Islands (FAAC). Not to mention the many anonymous people who accommodate prisoners in their homes while they are on leave, or help them with various administrative paperwork, job-hunting, etc.

In addition, the ‘Proyecto Patrones’ was launched in early 2025. Its aim is to build the capacity of lawyers working on the islands, to raise awareness of the reality of the criminalisation of captains in Spain and to strengthen links with existing coordination networks. Proyecto Patrones is part of the Captain Support Network, made up of organisations fighting against the criminalisation of captains, mainly in Greece, Italy and the English Channel.

Faced with a system that treats people as criminals from the moment they arrive on European soil, whether or not they have actually committed a crime, the greatest resistance is to continue to exercise one’s right to migrate by defying borders. Y. has a few months left to serve before completing his sentence. Faced with the prospect of possibly being sent back to Senegal as soon as he is released from prison, his choice is clear: ‘I’ll be back.’

4. Shipwrecks

The year 2024 concluded with several deadly shipwrecks and 2025 has continued this devastating trend. The grief pushes us to continue to fight for freedom of movement to end mass deaths at sea. Until then, we stand in solidarity with all families of those who disappear and will continue to struggle by their sides when they demand answers. Many shipwrecks remain invisible, and when bodies are not found and identified, families are stuck without knowing what happened to their loved ones. We will not forget those who have lost their lives or went missing.

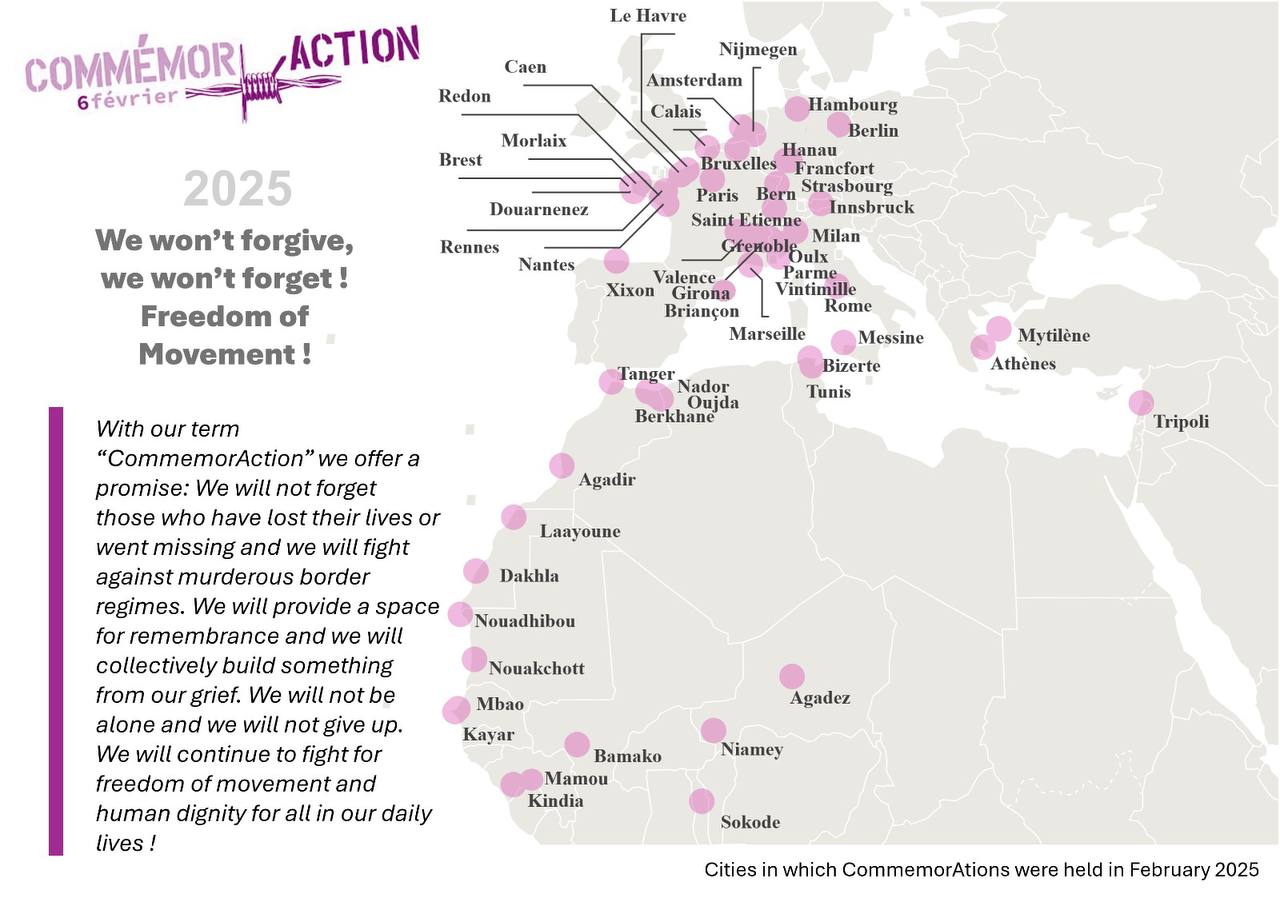

CommemorActions 2025. Source: AP

On 2 September, four people were found dead, and around ten people are missing, off the coast of Dellys, Boumerdès in Algeria. Four survivors were rescued.

On 3 September, a boat departed from Tipaza in Algeria, heading to Spain. The authorities were alerted. But since that day, there has been no news from them, and the 14 people went missing.

On the same day, 17 people went missing after departing from Dellys in Algeria.

On 4 September, one person was found drowned, their body washed ashore off Juan XXIII in Ceuta.

On 8 September, a pirogue with around 200 people capsized ten minutes after departure only four kilometers off the coast of Tefess, Mbour, in Senegal. Only 20 people survived, at least 6 people were found dead and around two hundred people went missing.

On 9 September, one person was found drowned, their body washed ashore at Desnarigado in Ceuta.

On 15 September, one person was found dead off the coast of Findeq in Morocco, after attempting to swim to Ceuta.

On 18 September, two people were found drowned after trying to escape the Moroccan Gendarmerie royale/police force, 25 kilometers off Taghazout near Agadir. More than 60 other travellers on the boat were intercepted and arrested.

On 21 September, one person who had tried to swim to Ceuta was found drowned near Kabila Beach, M’dig, in Morocco.

On 20 September, 65 people left from Mauritania. They are still missing to this day.

On 22 September, a pirogue was found drifting off the coast of Mamelles, Dakar, in Senegal. More than 150 travellers were on board when the boat departed from Mbour on 13 August. At least 30 bodies were found dead.

On 27 September, only four people survived after the shipwreck of a boat with 61 people who left from Tan-Tan on the 22nd. Two of them were hospitalised.

On 28 September, nine people, including a child, were found dead and 27 people were rescued after a shipwreck of a boat six kilometers off the coast of El Hierro, Canary Islands. 57 more people are missing. The boat had departed from Nouadhibou in Mauritania.

On 7 October, one person died and eight were arrested after the Moroccan coast guards tried to stop the departure of around 60 people in the area of Rakbat al-Jarf, 25 kilometers south of Tarfaya in Morocco. The people on the move threw stones at the coast guards and the coast guards fired gunshots. A motor inflatable boat with two 25-liter fuel containers was seized by the authorities.

On the same day, one person was found dead and 16 survivors were rescued by Salvamento Marítimo from a boat 27 miles off the coast of Cabo de Gata, Almería, after a pleasure boat alerted to its location. The boat had left from Algeria.

On 11 October, one boat that had departed from Tipazza in Algeria was found after drifting for 11 days, 100 miles east of Palma between Menorca and Sardinia, in the French Search and Rescue zone. Only three people survived; two of them were brought to the hospital. 11 more people are missing.

On 13 October, three people were found dead and 29 survivors were rescued by Salvamento Marítimo 52 miles off Garrucha in Almería.

On 26 October, a boat from Senegal arrived in La Restinga, on the island of El Hierro (Canaries, Spain). Unfortunately, one person among the 174 travellers had lost their life during the trip.

On 27 October, a team of fishermen found the remains of a 19-year-old boy near the coast of Alhucemas (Morocco). He had attempted to cross to Ceuta.

On 28 October, two people died on a boat with 81 people that was intercepted at sea near Nouadhibou. Another passenger of this boat died shortly after in a hospital.

On 31 October, a boat with 150 people arrived in Nouakchott, after being at sea for more than 10 days. 28 people lost their lives during the trip, and 30 other passengers arrived seriously injured.

On 1 November, a boat arrived on the island of El Hierro carrying 207 people. Four people had been killed by the boat crew during the trip.

On the same day, seventeen dead people were discovered in Ouriora Beach, near Guelmim (Morocco).

On 2 November, a wooden ship that had left from the north of Mauritania nearly three weeks before was found by drifting 370 kilometers south of El Hierro by a merchant vessel. From its 58 passengers at departure, only 10 people remained on board, and 48 had died during the trip.

On the same day, one person died at an insular Hospital in El Hierro (Canaries, Spain) from injuries sustained during her travels.

On 3 November, 160 to 180 people were declared missing. Their boat had departed on 20 October from Djifère (Senegal). They are still missing.

On the same day, five people lost their lives during a shipwreck 90 kilometers off the coast of the island of Lanzarote (Canaries, Spain).

Still on the same day, near Lanzarote (Canaries, Spain), a person was found dead after falling from a dinghy that was beginning to deflate.

On 4 November, one person was found dead among the 150 passengers of a boat that was found adrift around 320 kilometers south of La Restinga (El Hierro, Canaries, Spain).

On 5 November, off the coast of Puerto Naos (Lanzarote, Canaries, Spain), a fisherman found two young people dead. One of them was wearing a life jacket and the other had a tire tube wrapped around his chest.

On 6 November, thirteen people were found dead, ashore off White Beach near Guelmim (Morocco)

On 7 November, one person was declared missing after a boat initially carrying eight people arrived near Almería (Spain) with only seven people on board.

On 14 November, a coastal fishing boat found a dead person off the coast of Kilati (Morocco).

On 18 November, two dead people were found on a beach between Almerimar and the El Ejido lighthouse (Spain).

On 28 November, a boat was rescued off the coast of Adra (Spain). On board two people were alive and two people were dead. Seven people were declared missing and were still missing when the search for them ended three days later.

On 1 December, 8 people were declared missing on a boat transporting 18 people.

On the same day, fifteen dead people were found washed up by the sea a few miles off the coast of Raïs Hamidou (Algeria), a week after leaving Algeria on a traditional boat. Five people remain missing from the same boat, and only three people survived.

Still on the same day, seventeen people and their boat that departed from Algeria on 28 November were declared missing.

On 2 December, one dead person was found off the coast of Los Escullos (Spain). He was allegedly forced to throw himself into the sea to disembark, along with a group of 16 other people.

On the same day, 16 people who had left Zeralda (Algeria) on a boat the day before were declared missing.

On 4 December, one person died during a 15-people boat trip from Algeria to Spain.

On the same day, a group of 23 people that left Algiers towards the Balearic Islands (Spain) were declared missing during a bad weather period. They are still missing.

On 7 December, two people arrived in Almería, and nine people were declared missing after the shipwreck of their boat, which had left from Morocco on 26 November.

On 11 December, a dead person was found among 62 people, on a boat about 93 kilometers from the island of El Hierro (Canary Islands). The boat had left Nouakchott 3 days prior.

On the same day, five dead people were found among 81 people, on a boat that reached El Hierro (Canary Islands) after leaving Nouakchott five days earlier.

On 14 December, 2 people died, one was taken to a hospital in serious condition and five remain missing after a shipwreck that happened 60 miles from la Pitiusa menor (Balearic Islands, Spain).

On 17 December, a dead person was found at sea near the border between Tarajal (Morocco) and Ceuta (under Spanish authority).

On 19 December, four people drowned and another five remain missing after the inflatable boat they were travelling on sunk 137 kilometers off the coast of Lanzarote, Gran Canaria, Spain.

On 22 December, a dead person was found near the coast of Puertito de Güímar, Santa Cruz de Tenerife, Spain.

On the same day, six people drowned after a boat with 34 people sunk off the coast of Nouadhibou (Mauritania).

Still on the same day, a dead person was found on the beach near Fuente Caballos (Ceuta, under Spanish authority), and another dead body was found on the beach of Chorrillo (Ceuta, under Spanish authority).

Still on the same day, nine survivors from a boat that had departed from Mauritania and shipwrecked reached the land. The number of dead is not precisely known.

On 26 December, one person died and four were taken to a hospital in serious condition. They were among 55 people who were found 100 miles south of La Restinga (Santa Cruz de Tenerife, Canary Islands).

On the same day, 69 people died and only 11 people survived the shipwreck of a boat off the coast of Morocco.

On 27 December, around a hundred people were declared missing. Their boat had left Saint-Louis (Senegal) two weeks before and they haven’t been heard of since.

On 28 December, a shipwreck 10 kilometers off the Algerian coast, near Boumerdes, left 28 people missing and only 3 survivors. Several minors and a woman in advanced pregnancy were traveling.

On 29 December, around 60 people were declared missing. The boat they were travelling on had left Mauritania on 18 December and was aiming for the Canary Islands. They are still missing.

On the same day, 18 people left Tipaza in Algeria and went missing. Later, two bodies were found dead in Jilel.

Still on the same day, around 12 people left from Bourmedes in Algeria. Since then, the people went missing and the boat possibly shipwrecked.

On 1 January, a boat arrived by its own means off the coast of Las Galletas in Tenerife, Canary Islands. 69 people survived, and two people lost their lives.

On 2 January, around 90 people left Nouakchott on a wooden boat. The boat was found off Dakhla later that month, with 36 survivors. 14 people were found dead. Many people are still missing.

On 4 January, one dead body was found by the Guardia Civil near the Santa Catalina cemetery in Ceuta. The person, about 20 years old and from North Africa, was wearing a neoprene suit and fins, which indicates that he may have tried to swim to Ceuta.

On 7 January, two dead bodies were found by tourists near the beach of Es Cavall d’en Borràs in Formentera, Balearic Islands. They had died a few days before, possibly after trying to cross the Mediterranean Sea.

On 8 January, one person was found drowned by the Spanish coast guard off Sarchal Beach near Ceuta, probably after having tried to swim from Morocco.

On 10 January, one person was found drowned 200 meters off the coast of s’Arenal de Llucmajor in the Balearic Islands by the Spanish coast guard.

On 15 January, one person was found drowned on the beach of Sa Torreta, S’Espalmador in Formentera, Balearic Islands.

On the same day, the Moroccan Marine Royale found a boat 60 miles off Al-Dakhla in Western Sahara, three days after the Morrocan and Spanish authorities had been alerted. The boat carried 86 travellers when it left from Nouakchott in Mauritania on 2 January. On 15 January, 36 survivors were rescued, 15 people lost their lives, and 30 people are missing.

On 22 January, one dead body was found among the 68 people on a boat rescued by the Spanish coast guard, three kilometers south off the port of La Restinga, Santa Cruz de Tenerife in Canary Islands.

On 23 January, two people wearing neoprene suits were found drowned near Santa Catalina in Ceuta by the Spanish coast guard.

On 25 January, a boat that left from Senegal on 11 January arrived in the Canary Islands after more than 10 days at sea. At least 3 people died.

On the same day, a group of 25 people departed from Algeria on a small boat heading to Cartagena and then went missing.

On 27 January, 50 people left Morrocco for the Canary Islands on a boat and then went missing.

On 29 January, 19 dead bodies were found by the local coast guard off the coast of Basseterre, Saint Kitts and Nevis in the Caribbean Sea. It seems that the travellers were from Western Africa, and it is possible that the boat was heading to the Canary Islands and got lost in the Atlantic Ocean.

On 2 February, nine people were found dead in a boat off Nouadhibou in Mauritania after having departed on 25 January. Among the 32 survivors, 10 were in critical condition and taken to the hospital by the Mauritanian Red Crescent.

On the same day, one person was found dead on the beach of S’Alga in Formentera in the Balearic Islands.

On 3 February, another person was found dead on the same beach.

On 4 February, one person was found dead on the shore at Playa de la Almadraba in Ceuta.

On 7 February, one person, probably between 20 and 30 years old, was found dead in the sea in the vicinity of La Sirena in Ceuta.

On 12 February, a boat was rescued 20 kilometers south of El Hierro in the Canary Islands. One person, whose name was Salif Coulibaly, was found dead, and at least two people went missing. 77 people survived, among them ten women and a baby. Eight people needed medical attention, and one person was hospitalised.

On 15 February, a boat that had departed from Mostaganem in Algeria shipwrecked 50 kilometers off Cartagena, Spain. Three people lost their lives, and seven people survived.

On the same day, 60 people left Mauritania towards the Canary Islands and went missing; the boat has not been found since.

On 17 February, after a shipwreck near Águilas, Murcia, one person died. 25 survivors were brought ashore.

On 19 February, one person between 30 and 40 years old was found dead, floating with a life jacket a few meters off the beach of Santo Tomás on the island of Es Migjorn in Spain.

On 20 February, 22 people departed from Algeria towards the Balearic Islands. They have been missing since then.

On 23 February, five people died trying to reach the shores of the Balearic Islands, 37 kilometers off the coast of Ibiza. Four of them lost their lives trying to help one of their companions who fell into the sea. 19 people survived, six of whom needed medical attention for dehydration and hypothermia. The boat departed from Aïn Taya in Algeria on 17 February.