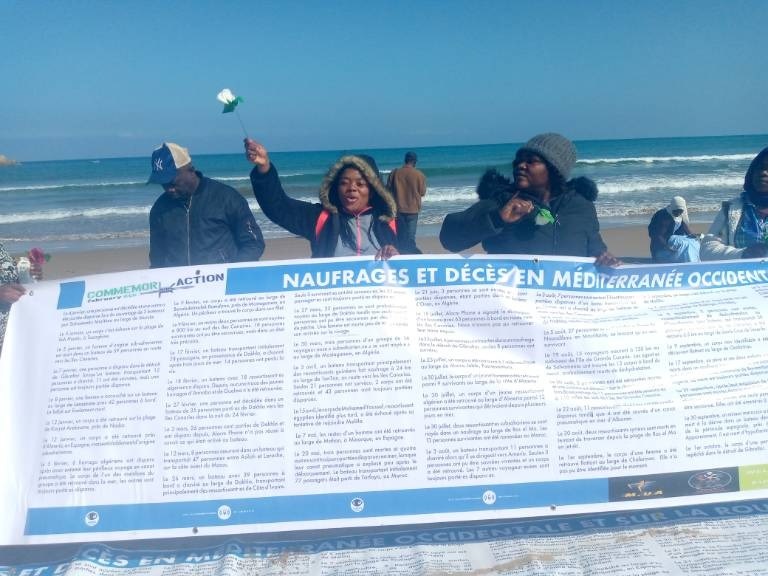

Private memorial at Tanger beach, 6th February 2023. Source: Alarm Phone

1 Introduction

On 6 February 2014, at least 15 people were killed when the Spanish Guardia Civil opened fire on a group attempting to reach Europe by swimming around the border fence at Ceuta. The killing became known as the Tarajal massacre. It was not the first mass killing by the authorities in an attempt to prevent people from moving across borders without permission from above. It was also far from the last. We, along with the affected communities, are still reeling from the mass killing on 24 June last year when Moroccan and Spanish forces murdered at least 37 people at the border fence of the Spanish enclave Melilla. Hundreds of people are missing, and an unknown number of bodies were buried anonymously by Moroccan state authorities. Instead of investigating and prosecuting those responsible for the killing or even just rethinking their inhumane border policies, the authorities have instead chosen to railroad 87 of the victims into prison on the pretence that they were responsible for the deaths.

These high-profile mass killings are just some of the more notorious deaths at the border. They are by no means an aberration. The European Union has militarised and externalised its borders in an attempt to prevent those they consider unworthy of the right to free movement from coming to Europe. The people targeted are those deemed ‘the other’ in the imagination of Europe’s rulers. It is nothing but racism in its crudest form. Borders kill every day. Every time somebody chooses to embark for the Canaries in an overloaded, unsuitable boat in the hope of making a life for herself in Europe, a life is put at risk. It is put at risk because of the Spanish State and the European Union’s border policies. For European ‘leaders’, wealth can be and is extracted from your community, but you have no right to follow that wealth and build a life for yourself among the wealth plundered from your community and the communities of countless other people.

The journey across the Atlantic is, perhaps, the most deadly route to Europe, but there are no safe routes for those who are systematically denied visas. These reports are now an ever-growing litany of death. Because of the Tarajal massacre, 6 February has become an international day of commemoration and action, commemorAction, for those who have been killed by the rich world’s border policies.

CommemorAction is a ‘weapon of the weak’. It is a way of saying that these lives matter, these futures matter, each and every individual matters, and when she dies, we grieve. It is an attempt to intervene in the public space, to make the border and its murderous reality visible. Every time another life, another friend, is lost because of the border regime, people gather to commemorate that loss. Marking that death is important. This is also CommemorAction. Inspired in part by Chamseddine and the Cemetery of the Unknown in Zarzis, when an unknown body is washed up or is taken to the morgue, activists go to identify the body. If the person can be recognised, they notify the family. When that is not possible, the body is given a dignified burial. It is a practice that happens all around the region on both the European and African sides. This too is commemorAction.

Though the core of our work is running a 24-hour hotline to bear witness to the sea border and to support people to insist that their rights are respected, our project itself is a piece of commemorAction. As the European authorities harden their hearts and ignore people’s cry for help, we become more and more a project that is documenting and commemorating each and every death. We do it so that when this border regime is over, no one can say that they did not know. More importantly, we do it because we already know. When confronted with injustice, you have to act. The bare minimum must be to commemorate the dead, demand that the perpetrators are held to account and action be taken to prevent the injustice from being repeated.

The violence perpetrated by the border regime is a crime on a grand scale. We do not have the power to order the killing stopped. We do have the power to make it visible. Borders, as is well-known, are everywhere, but their effects are hidden. Borders are hidden not because they cannot be seen, but because there is a wilful refusal to engage with what is right in front of us. On 6 February, people gathered to bring the violence of the border into focus and commemorate the dead.

In this report, we document what happened at some of the commemorActions across the Western Mediterranean and Atlantic region. We have also made space in the report for the voices of those who have seen their loved ones killed by the border. In this way, we hope to make this report a commemorAction. For now the pain is too often solely a private one; for things to change it must become a public one. May the memory of those who have died be for a blessing.

A note on focus and terminology

Alarm Phone is a network of volunteer activists. The bulk of Alarm Phone members in the Western Med and Atlantic region are West African or European in origin. As a consequence, we are much more embedded within the communities of people on the move from West African countries than we are from the Harraga communities of the Maghreb. This inevitably leads to the underrepresentation of the experiences of the latter group. The only way to rectify this problem is to expand what we do and work to build a truly transnational community of resistance. This is slow and laborious work, but we are committed to doing it.

The language that we use is important. The words that we use also carry the weight of their history, and that is a history of power. We constantly struggle to view the world correctly and to find the right descripition of what we see. There is no single viewpoint that will encompass everything. To see the world correctly, we need a kaleidoscopic view. This report is a collective endeavour. Many of the authors are not writing in their first language, and most of the witness testimony is also given in a second or third language. We consider this a strength. We do not wish to regiment the language used in our descriptions of people and their backgrounds. Where someone might baulk at ‘sub-Saharan’ as implying inferiority and prefer ‘Black’ or ‘black African’, another might reject the racialisation implicit in the latter terms. Equally, some of us avoid talking of ‘migrants’ and prefer to emphasize personhood with ‘people on the move’, but for others of us this language is fussy and unnatural and we are proud to be migrants. We have left, as much as possible, the authors’ different choices of description, especially where the author is herself a person on the move.

2 Commemoractions

“6 February 2014 was truly a landmark day. Many people lost their lives, many families lost their children, many women lost their husbands, many children lost their fathers. This day was very important for all the migrants and all the people who make the crossing in very difficult circumstances, whether it is in the context of land borders, the fences, or the sea, be it the Mediterranean or the Atlantic. This day of 6 February has compelled people, migrants and activists all over the world, to make this day a historical monument for all missing migrants. We honor those who lost their lives. It is also important for all those who have lost brothers and sisters to remain strong, encouraged and motivated. Let’s continue in the same way, in the same struggles, hoping that one day, maybe things will change.” (local AP activist)

The number of commemoractions that took place this year is really impressive, with more than 40 actions around the same date. To spread the idea, Alarm Phone released a powerful video that captures moments of previous commemoractions and is available with English, French or Spanish subtitles.

2.1 CommemorActions on the Atlantic Route

The Atlantic route is known as one of the most deadly routes for migration in the whole world. According to the official statistics of the IOM Missing Migrants Project, 559 people died or went missing on the Atlantic route in 2022, which amounts to 8% of all of the deaths recorded by the project worldwide . Yet, the Missing Migrant project reckons that the number of unreported deaths must be much higher. The NGO Caminando Fronteras counted 1,784 people dead or missing on the Atlantic route in 2022. In the second week of February 2023 alone, around 100 people lost their lives (see section 6: Dead and missing). Several boats that Alarm Phone supported in the last months resulted in horrific shipwrecks, for example a boat on 7 December 2022 and one on 7 February 2023. We commemorate all of these people; people whom we may have spoken to on the phone, or whom we may have passed once in a street, whom we did or did not know, whose faces we saw smiling in the pictures we received from their families. You are still with us. You will not be forgotten.

CommemorAction in Laayoune on 4 and 5 February. The Atlantic route is one of the most lethal migration routes worldwide. Source: Alarm Phone

In collaboration with two other associations, ADIPROS and ARSEREM, the Laayoune Alarm Phone team organised two commemorAction days on 4 and 5 February at the Caritas centre in the town. Many members of different communities came together to commemorate, pray and pay tribute to the many people missing and dead at sea on the Atlantic route and elsewhere. Family members were also present and gave testimony of their experiences and their pain. One person, for example, mourned for his wife whilst another person spoke of their five-year-old daughter lost en route to the Canaries.

There were also political discussions about the lethal character of the Atlantic route, and a working group was put in place for research and identification of the missing and dead. Further debates were organised around the topic of safety at sea and how important it is to always check the weather forecast before travelling. The representives of the different communities once again highlighted how human rights are violated in the region. The commemorAction was a powerful call for human dignity and the need to stand together, to support one another in our grief and our fight.

On the Canaries, for years now, some activists have made a practice of commemorAction and have been trying to support the families of the disappeared and the dead. On Fuerteventura, the association EntreMares organises a small commemorAction in a public square in Puerto del Rosario whenever there is a shipwreck on the Atlantic route. On Gran Canaria, there is a commemorative plaque that people sometimes gather around after a shipwreck. On Lanzarote, the Red de Solidaridad helps bury the dead in the small Muslim section of the Teguise cemetery. Activists and local people try to keep the inscriptions on the improvised tombstones visible and sometimes come to place flowers on the graves. Many of the dead could not be identified, their tombstones carry names like “Undocumented Number 3”. Other bodies were identified and buried under their names, notably the victims of three shipwrecks, one on 6 November 2019 (Caleta Caballo), one on 24 November 2020 and one on 17 June 2021 (Órzola).

Tombstone in the Teguise cemetery on Lanzarote, where the grave has been marked as “Undocumented”. Source: Activist

2.2 “Migrate to live not to die”: Dakar, Senegal

On 6 February 2023, nearly 200 people gathered in the ocean-facing town of Thiaroye-sur-Mer, Senegal, to honour those who have gone missing or died along the migration routes, and to educate one another about the political actors who are responsible for the deaths.

The event was organised by Boza Fii, an association of people who have returned to Senegal, and Alarm Phone Dakar in collaboration with Association des Jeunes Rapatriés de Thiaroye-sur-Mer (AJRAP) and Association Ben Thiaroye-sur-Mer. Among other associations, Migration Control, Énergie de Droits Humaine Senegal, Sama Chance, Village du Migrant, the Municipality of Thiaroye, Alarm Phone Marseille, the president of the Resau des Femmes de Thiaroye and journalists from CQFD Marseille attended and contributed in a spirit of building alliances against a lethal border regime.

“It is important to expand these initiatives to make the population understand exactly what is happening” a participant stood up to say, saluting the work of Boza Fii and the fact that Senegalese youth are organising themselves to change the situation.

“Many people in Senegal do not really understand what happens in the border regions”, Saliou, the President of Boza Fii, later explained. “It was really important to show the video reconstruction of what happened at the massacre at Melilla in June 2022”, noted Ibrahim, a core Boza Fii organiser.

“It’s forced death. It’s organised”, the Boza Fii team explained. “It was emotional. They finally understood”, recounted Ibrahim. “It’s truly a massacre.”

“Lots of people think, oh, it’s just that people take risks, it’s clandestine migration, it’s irregular migration, they should just stay in their countries”, explained Saliou. “That’s what many politicians say. But it’s that ideology we want to challenge.”

The team showed statements issued by the Spanish president immediately after the massacre and videos of subsequent public interventions made by certain African ambassadors, including the ambassadors of Chad and Cameroon in Morocco, who exonerated the Moroccan and Spanish authorities and placed the blame on the people who attempted the crossing. “We need to understand in our country how we are being represented abroad,” Saliou said. “It’s true we cannot do the work of the government. But we can denounce what they do so that in the future it will be better.”

After lunch, the participants walked to the nearby beach. Aïda Thiam from Boza Fii read out the call for justice, truth and reparations issued in advance of a series of commemorAction events.

Awa Ba, who lost her son Mamadou Ndiaye after he tried to make it to EUrope, explained how she went to the responsible authorities asking about what happened to her son. She called for the authorities to look for her son. Up to now the authorities have not found anything. She explained that she still goes to meetings to ask for information and to demand action. After that, everyone prayed in silence according to their own beliefs; then the participants threw flowers into the ocean together and watched the waves wash them away.

“It wasn’t easy, the event”, reflected Ciré. “But we are already engaged. We cannot just drop it.” He summarised the sentiment of the closing discussion with the words: “We are already here. The struggle goes on.”

CommemorAction Dakar, 5th February 2023. Source: Boza Fii

CommemorAction Dakar, 5th February 2023. Source: Boza Fii

CommemorAction Dakar, 5th February 2023. Source: Boza Fii

2.3 Tangier, Morocco: Public Debate, Private Memorial

On 5 February, the Tangier Alarm Phone team organised a public debate on the theme of CommemorAction in collaboration with the Moroccan association Chabaka and with the support of Conseil des Migrants Subsahariens au Maroc (CMSM), Pateras de la Vida Larache, and Association Marocaine des Droits Humains (AMDH) Nord.

In opening the event, members of Alarm Phone and Chabaka highlighted how, in commemorating and seeking justice for the terrible events of 6 February 2014, we also have an opportunity to discuss border violence more generally, remember those we have lost, and debate how to respond. “The day has become a symbol”, a Moroccan comrade in the audience emphasised. “It was a day when the violence of border controls, often more hidden, was out in the open for all to see.”

“Each day there is a tragedy”, noted a Cameroonian activist. “It is a very important day for me. I cannot forget”, added a participant visiting from Nador.

Though the practice of marking 6 February 2014 only began as an international practice of CommemorAction in 2018, Boubker, a celebrated Moroccan activist and founder of Chabaka, situated it in a long history. He described earlier rounds of border violence and resistance, including the caravans Chabaka organised every year for nine years following the massacre of 2005 in Ceuta. “Today we [migrant solidarity movements] are very weak compared to then.”

The conversation turned from honouring those we have already lost to a forward-facing struggle for justice, truth and reparations. “We need to work together”, Senegalese, Cameroonian and Moroccan comrades each repeated. They underlined how informal solidarity networks and officially registered organisations might usefully cooperate, to interface between mobile communities and state institutions.

Families of the missing and dead were wary to participate in this public event – just as many are wary to submit official requests for information – out of fear of political recrimination, the emotional pain involved, or both. “It’s so important families know their rights”, insisted Hassane, the president of the Association Aides des Migrants en Situation Vulnérable AMSV Oujda Maroc. “Before, they didn’t have the right to make these demands, but now they do. So they must know.” He explained how his organisation also creates supportive spaces where families can simply socialise with one another and come to understand that they are not alone. Members of different sub-Saharan community associations reflected on how they do something similar.

“Do you check the prisons from time to time?” a participant from Senegal raised her hand to ask. “Because when there’s someone in Tangier whom we no longer see, we often say they’re lost at sea. But they’re not in the water; they’re in prison.” An ex-detainee in the audience confirmed: “There are people [in prison] who live with… [a] false name – for one year, or ten years.” He reported how people were taken in straight from the boat, with no one to visit them. Only family members have the right to visit someone incarcerated by the Kingdom of Morocco, it was explained. This makes it difficult for people from other African countries imprisioned in Morocco, as there family members are unlikely to be able to obtain a visa for the country.

Recognising faces from the pictures of the missing or dead displayed on the wall, an attendee from Cameroon emphasised the importance of the event and that even more people need to come in the future.

CommemorAction in Tangier. Source: Alarm Phone

Private Memorial in Tangier. Source: Alarm Phone

2.4 Ceuta, a Spanish enclave: The March for Dignity

On Saturday, 4 February, 200 people from around the world met in the Spanish enclave of Ceuta and marched to Tarajal beach, the site where in 2014 Spanish border guards shot rubber bullets and threw gas canisters at a group of around 200 people in the water, killing at least 14. The organisers of the X Marcha por la Dignidad collected signatures from more than 252 organisations calling for justice, truth and reparations. At the university, geopolitical analyst Sani Ladan, lawyer Patricia Vicens, journalist Youssef M. Ouled and Ceuta-based activist Soda Niasse debated the meaning of the deaths, racism, the response from the authorities and the notion of incremental genocide. In the sunlight, members chanted “justice” as they walked in a steady line. At the beach, they formed a circle and lit a candle for each of the individuals who died.

The march for dignity. Source: @centre_IRIDIA

Lighting candles at Tarajal beach. Source: @marchatarajal

2.5 In the region of Nador: Repression continues

AP Nador/Berkane commemorated together with the association Mouvement Uplift Africa at the beach at Cap de l’eau with speeches, banners and flowers. Unfortunately, in this region not surprisingly, the activists were observed by the police and were taken to the local police station, where they had to endure an investigation for a few hours. Fortunately, all were released at the end of the day.

CommemorAction at Cap de l’eau, Source: Mouvement Uplift Africa

2.6 CommemorAction in Oujda

For the ninth CommemorAction of the tragedy of Tarajal in Oujda, the local AP team organised several activities in the presence of families of the disappeared, human rights activists, journalists and other members of NGOs and local associations.

The first activity took place on Saturday, 4 February at the centre of the Democratic Confederation of Labour in Oujda under the title “From the massacre of Tarajal to the massacre of Melilla”. There were three axes of discussion. The first focused on the psychological suffering of the families of the disappeared and addressed the psychological disorders which affect the parents and other family members as well as the lack of psychological support in these cases. The second axis was about the massacre of Melilla on “Black Friday” and the suffering of the migrants during the intervention of the Moroccan gendarmerie. There was also a discussion of the arrests of some of the people who could neither cross nor flee. Finally, the third axis dealt with the role of the media in migration issues. After the discussions, the participants lit 50 candles in memory of the victims of the massacres at both Tarajal and Melilla.

The second activity on 5 February consisted of a mixed discussion group, made up of young Moroccans and migrants of all genders, who discussed the issues of migration together and shared their opinions on the massacres at Tarajal and Melilla. They also spoke about racism in the city of Oujda.

CommemorAction in Oujda. Source: Alarm Phone

3 Sea Crossings and statistics

According to UNHCR statistics, 6,554 people arrived in Spain between 1 November 2022 and 28 February 2023. In the same period, Alarm Phone was involved in 51 cases, of which 29 calls came from the Atlantic region, 11 from the Alboran Sea and 11 from the Algerian route. According to the people who alerted us to them, the boats were carrying at least 2,036 men, 233 women and 67 children, adding up to a total of 2,336 people.

22 of the boats Alarm Phone was contacted about were rescued by Salvamento Marítimo, nine were intercepted by Marine Royale, four boats returned by themselves and at least three boats completed the journey on their own. As a relatively new development, in at least four cases merchant vessels were involved in rescue operations. They did not always abide by international agreements. One such example is the case of 12 February, in which the merchant vessel Santa Isabel of the Maersk Group brought 47 people in distress back to Western Sahara, thereby ignoring the requirement to disembark shipwrecked mariners in a port of safety and violating the Refugee Convention’s principle of not returning an asylum seeker to a place where she may be in danger. It is vital that SAR authorities and merchant vessels take into account people’s rights as refugees when allocating a port of disembarkation. Unfortunately, many people’s fate remains unclear. For example, 53 people left Tan-Tan at the beginning of December. They were lost at sea for two weeks. Three survivors were found on the cliffs of Tantan. The other 50 are still missing.

We are sad and angry about the three shipwrecks Alarm Phone had to witness. These led to at least 100 deaths and 101 people who are still missing.

These shipwrecks are just a fraction of the tragedies that are a more or less daily occurrence on the Western Mediterranean and Atlantic routes. The Missing Migrants Project of the IOM reckons that the Western Med and Atlantic routes in 2022 are so lethal that they account for just under 20% of all the deaths of people on the move worldwide. Caminando Fronteras puts the number of people who died last year on their way to Spain at 2,390, which means more than 6 deaths each day. With 1,784 people dead on the Atlantic route alone, this route remains one of the deadliest in the world.

Our thoughts and solidarity go to the families and friends of all the people who have died during their journey or are still missing. We commemorate the dead and disappeared. We commemorate Chahira, Boudjrada, Belkada, Ayoub, Abdou, Reda, Rasim, Daimi, Anayis, Lotfi, Djalal, Lilia, Ryad, Laoulou, Islam, Benachir, Mohamed, Aiman, Hamid, Hanan, Abderramin, Ismail and all those whose names we don’t yet know.

4 Updates from different regions

4.1 Atlantic route

The last two months of 2022 did not see as many people crossing towards the Canary Islands as happened in November and December of previous years. Altogether, 15,682 people arrived via the Atlantic route in 2022, while numbers were around 22,000 in 2020 and 2021. 1,649 people had already come to the Canaries by 19 February this year. The first week of February was particularly busy. To all of them, we say welcome to Europe!

Although there are generally fewer boats that come from countries further away like Senegal or Mauritania, some people still try. A boat carrying people from The Gambia shipwrecked in December, resulting in 12 deaths. A boat which had left Mauritania was intercepted right after departure by the Mauritanian authorities. However, a large boat carrying 162 people made it to El Hierro, the most western of the Canary Islands, in late November. Another noteworthy story was the arrival of three people who braved the long journey from Nigeria on the rudder of a cargo ship and survived.

A worrisome development in the region is a possible resumption of deportations from the Canary Islands to Senegal. A deportation flight from mainland Spain made a stopover in the Canaries to pick up more than 15 inmates from the Gran Canaria detention centre. They were deported to Dakar on 14 February. This came after a meeting on 26 January between the Ministers for Foreign Affairs of Senegal and Spain.

4.2 Nador – Melilla

Raids of makeshift migrant camps, arrests and arbitrary expulsions to the south continue to be the brutal reality in and around Nador.

On 24 June, at least 40 people were killed by Moroccan and Spanish border guards in the attempt to cross the border towards Melilla at Barrio Chino. For further details, see e.g. our last report, a BBC documentary, a report by Amnesty International and a report by Caminando Fronteras.

The trials against several groups of people, mainly from Chad, Sudan and South Sudan, who are being scapegoated and prosecuted for these events are still ongoing. On 17 November, the sentence for a group of 14 people previously sentenced to 8 months in prison was increased to 3 years of imprisonment by the Court of Appeal in Nador. On 9 January, the Court of Appeal also increased the prison sentence against 13 others (2 Chadian and 11 Sudanese nationals) from two and a half years to 3 years. On 6 February, the last appeal verdict was issued in the Nador court, with 3 detainees being sentenced to 4 years of imprisonment. Meanwhile, on the other ‘side’, the Spanish prosecutor’s office investigation into the real culprits “found no evidence that any wrongdoing was committed in the behaviour of the Spanish security forces”. Spanish Minister of the Interior Grande-Marlaska likewise denied that there were any deaths or any neglect of the wounded on the Spanish side of the border. Nevertheless, a detailed, forensic investigation by Lighthouse Reports uncovered multiple abuses by the Guardia Civil and Spanish authorities.

Sudanese families are still contacting the human rights association AMDH Nador to look for their children missing since the tragedy (79 people are reportedly missing). AMDH Nador continue to publish pictures of the missing on their Facebook page, trying to reach out to the migrant communities to find any information on their fate.

At least the good news is that the much hated and much resisted illegal detention centre in Arekmane was finally closed. AMDH Nador fought a long fight for its closure as detainees were held under unlawful conditions. The centre will now again be used for its primary purpose, as a sports and leisure centre for youth.

Sea crossings by the Black African communities in Nador seem to have resumed. We saw the arrivals of two boats on 13 January. The first carried 45 people, including, according to the classification opf Emergencias Frontera Sur Motril, three children and two minors. The second boat had twelve people. It was made up of five children, four women and three men, according Helena Maleno’s classification. Both groups embarked in Nador and arrived in Motril. On Christmas eve, 30 Black Africans (16 women and 14 men) arrived on the Spanish island of Chafarinas off the coast of Nador. They were transferred to Melilla two days later. This is amazing news: In the past, arrivals on the Spanish islets have tended to result in illegal pushbacks to Morocco. Also on 5 February a boat carrying 36 passengers (24 men, 10 children and 2 women) arrived on the uninhabited island of Alborán. Like those who arrived on Chafarinas, these travellers were also taken to an inhabited part of the Spanish state (Source and classification: AP Nador). Boza! [Boza is the (Bambara) word that is used across all communities of departure to celebrate a successful arrival to EUrope].

Moroccan nationals continued to cross, both to mainland Spain and to Melilla. The vast majority of Moroccan citizens, like those from south of the Sahara, now have to cross by boat or jump the fence to get to Melilla, as the official border crossing has been closed to them. The response of the Moroccan authorities has been one of severe repression. After an attempt by a group of Moroccan harraga to jump the fence on New Year’s Eve was thwarted, the authorities of Nador arrested about 40 young people. They were placed in detention, despite a lack of judicial authorisation, before they were forcibly relocated by bus to the interior of Morocco.

4.3 Oujda and the Algerian border zone

New deaths have been reported by the Moroccan Association for Human Rights (AMDH) Nador in the Algerian-Moroccan border area. On 14 December 2022, six (or in some accounts seven) lifeless bodies were found in the area of Ras Asfour, on the Moroccan side. The bodies were buried in the cemetery of the town of Jeralda so quickly that they could not be identified. AMDH asks:

“How is it possible that six migrants all die at the same time in a place where it is cold, but a short distance from a Moroccan residential area and checkpoints of the Moroccan army? What was the rush to bury the bodies without allowing representatives of the Guinean and Chadian embassies to identify the bodies?”

On 25 January 2023, two more bodies were found and buried in the same cemetery. In a Facebook post, AMDH Nador talks of “serial deaths”: eight people in less than 35 days. The organisation blames the Moroccan deportation policies. The public prosecutor opened an investigation at the end of January 2023.

The cemetery of Jeralda. Source: AMDH Nador

The methods used to keep this border closed endanger the lives of people on the move. Local AP activist Driss Elaoula explains that the area is very hostile for people on the move: difficult climatic conditions, but especially a border made manifest by a high iron fence made to hurt people who try to climb it. On the Algerian side, a dangerous pit was dug with holes 8 m deep and 4 m wide. In winter, these pits are often filled with water and people who try to climb the fence may fall in and freeze to death or drown.

In Oujda, the association Aides Aux Migrants en Situations Vulnérable (AMSV) works to identify the dead and arrange a funeral. The group has identified and buried 49 people in the last five years.

Regarding the situation of people on the move in Oujda, local AP activists report numerous arrivals in the city, mainly via the Algerian border. They usually leave directly to Nador. We are told by the same source that in the last months a lot of minors from Guinea arrived in Oujda and were forced to beg in the streets.

5. Dead and missing

On 22 November, a boat with 10 people capsizes and sinks off Gran Canaria; only one person survives, hanging on to some jerry cans for dear life.

In the first week of December, 12 people die during the journey from Senegal to the Canary Islands. The 7 survivors are rescued by the Moroccan Navy.

On 7 December, Alarm Phone is alerted to a boat with 53 passengers. As the Moroccan authorities do not respond to our alert, only 3 people survive. They are found close to the shores of Tan-Tan 14 days later.

On 9 December, Spanish authorities pick up a dinghy off Murcia, recovering 3 dead bodies and 6 survivors. 5 others remain missing.

On 10 December the Guardia Civil recover the body of a young Moroccan national off Benzú. He had tried to reach Ceuta swimming.

On 14 December, six or seven bodies (the number differs according to sources) are found in the Ras Asfour forest, near Oujda, on the border with Algeria.

On 15 December, the Guardia Civil find the body of a yet another young man who drowned off Ceuta.

On 16 December, a body is found on the Spanish side of the border fence separating Moroccan territory and Ceuta. The man died, probably after having jumped the fence.

On 22 December, the five survivors of a boat with 46 passengers are taken back to Asfi, Morocco. One of the survivors later dies in the hospital. The boat had spent 13 days at sea. Some sources even report 60 passengers.

On 30 December, 24 people are rescued from a shipwreck by the Moroccan authorities and taken back to Mirleft. Reportedly, there had been around 40 passengers. In early January, authorities put the count at eight missing and 15 confirmed deaths.

On 4 January, one dead body is found on a beach in Fuerteventura. A second body is found the following day. Although it cannot be confirmed, the two people probably drowned while trying to cross to the Canary Islands.

5 January, Alarm Phone is alerted to a boat with 80 or 90 people who had left Senegal two weeks earlier. A few days later we learn that the boat was found and the survivors taken to Cap Verde. The survivors tell us that 5 people did not survive the journey.

On 14 January, the Cape Verde authorities rescue 90 people who had been lost and adrift for 25 days. Two people die despite the rescue.

On 19 January, the body of one person is washed up on a beach in Fuerteventura. It is unclear when the person died and whether it was related to any shipwreck.

On 25 January, two bodies are found in the Algerian-Moroccan border zone; they are buried in the cemetery of Jeralda, Morocco.

On 31 January, four people are killed in a road accident. The Moroccan authorities were pushing 52 people on the move away from Laayoune when the bus overturned in the region of Tata.

On 5 February, the body of a young Yemeni national is found in Ceuta. He had been lost at sea six days earlier.

On 7 February, Alarm Phone is – among others – alerted to a boat with 46 people that had left Tan-Tan on 5 February. We later learn that they were picked up by a fishing boat. There are 43 survivors. 3 people are missing, presumed dead.

On 8 February, 43 people are rescued by Salvamento Marítimo, some showing severe signs of hypothermia. At least 8 people on the same boat had already died.

On 10 February, a fishing boat picks up 31 people and brings them to the harbour of Al Marsa, near Laayoune. According to Helena Maleno, the boat had left on 4 February from Tan-Tan with 65 people on board, meaning that 34 lost their lives at sea.

On 10 February, another shipwreck occurs near Boujdour. According to Helena Maleno, 36 of the 56 passengers die at sea, leaving 20 survivors.

On 12 February, Salvamento Marítimo rescues 23 survivors of a boat that had been lost at sea for 9 days. Six people lose their lives.