Originally published in Italian by Avvenire on 23. April 2020.

Translated to English by Alarm Phone.

A ghost fleet of Libyan ships manoeuvred by Malta to push migrants back. This time, the confirmation comes straight from Valletta, which, after facing NGOs’ complaints and the Avvenire’s enquiries taken up by the Maltese press, and after the open investigation against PM Robert Abela for the death of 12 migrants, has replied speaking of “cooperation with Libyan fishermen to make sea rescue more widespread”. This cooperation has been active for months and had never been revealed before.

The focus is on the motor fishing boat without name or international code used to rescue 56 survivors, who had been left at sea for 5 days. 5 of them reached Tripoli as dead bodies; 7 more are lost at sea. “They could have been saved”, the UN High Commissioner for Refugees stated in the past few days. Now, that boat has a name and a story to tell. While Malta stubbornly keeps hiding the name of the Libyan fishing boat, Avvenire has traced it back, reconstructed its controversial property passages and obtained an answer from Frontex, which attributes responsibility to the maritime authorities of the involved Mediterranean countries.

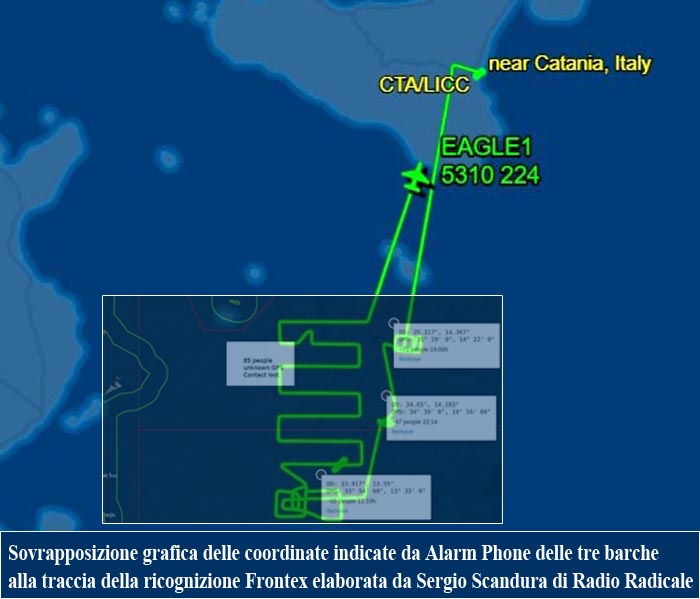

The rescue mission took place around dawn, on Wednesday 15th April. After 3 days waiting on the Libyan shores without any food, 63 migrants had left during the night between 9th and 10th April from Garabulli, 50 Kilometres south of Tripoli. Alarm Phone, along with Mediterranea and Sea Watch, had long asked for an intervention. These calls were ignored for 5 days, in a “passing the buck” mode, although the European naval forces knew everything since the beginning. When replying to Avvenire, the European Agency for Borders Protection wrote: “During the patrol flights over the weekend (between 9th and 11th April, ed.), Frontex’ planes identified several boats in distress. According to international conventions, we warned all the national Centres for Maritime Rescue in the area” – this is what a spokesperson reported in a written communication. That is to say, Frontex had alerted the centres for naval rescue operations in Rome, Valletta, and Tripoli. “According to international law – it is written – they, rather than Frontex, are the only bodies responsible for coordinating the Search and Rescue operations.”This statement was confirmed also by an analysis of the flights conducted by journalist Sergio Scandura from Radio Radicale, and then overlapped with an infographic by Mauro Seminara, director of “Mediterraneo Cronaca” (“Mediterranean’s Chronicle”). The Frontex flight’s route coincides, in the search positions and times, with the coordinates of the boats indicated by Alarm Phone.

The relevance of this statement could have a huge impact in the investigation against the Maltese PM, accused by various civic organisations of being responsible for the delayed rescue mission. But it could also be used by those lawyers who are preparing lawsuits for international courts. “The European Human Rights Court has already sentenced Italy and Malta for their criminal role in simile push-backs to Libya in several cases, but now, in light of the continuous and recent evidence of connivance and complicity with Libyan smugglers and torturers, it could be possible to pursue a lawsuit for crimes against humanity”, Giulia Tranchina, a lawyer specialised in asylum and migrants’ law for the London “Wilson Solicitors” law firm, observes.

Malta tries to justify its actions through an explanation on its national TV service. It admits that an agreement with Tripoli – and several commercial ships – exists, but for good purposes. “The Maltese government has already established some agreements, according to which private ships can, in case of need, help with migrants rescue”, the network TVM explains, attributing the source of this information to the government. Answering to some questions by one of the network’s presenters, a government’s spokesperson declared that “Malta was coordinating the rescuing mission of the boat lost at sea in a way that allowed migrants to be saved by private ships too.” Again, according to the government, “this is a normal procedure foreseen by the Search and Rescue Convention of 1979.” Curiously, the cooperation with “private ships” coordinated by Malta excludes humanitarian organisations’ ones.

At least, this time Valletta used a motor fishing boat. A fishing boat that was registered with at least two different names in Libya, but that, on international registers, results as Maye Yemanja (Imo Code: 7027459), inaugurated in 1970 and now showing a Libyan flag. Pictures do not lie. On another specialised website it is possible to find some more shots from 2011, when the boat had a Maltese flag, and its name and Imo code are well visible, painted on the side and aft. Instead, in the images of the landing in Tripoli, the boat was completely anonymous.

“During Easter weekend, Mae Yemanja was in Malta, in Malta’s Grand Harbour”, the Maltese investigative journalist Manuel Delia reconstructed. According to him, the motor fishing boat was in the main Maltese harbour and sailed in the evening of Tuesday 14th with no clear destination. “After the manoeuvres to leave the harbour, Mae Yemenja switched off its radar”, Delia explains. It would reappear in Tripoli in the late morning of 15th April, with on board 51 survivors and 5 migrants who died during the navigation.

The fishing boat has spent a big part of its 50 years in Malta. It was matriculated there and, until 2019, when it passed to a Libya-registered society, it belonged to a Maltese company which could be traced back to Carmelo Grech, the businessman everybody in Malta knew as Charles. Grech was recently cleared of charges after being sued for contraband, getting by even in Libya, where in 2015 he was found with 300,000 euros in cash. Initially, Valletta promised an enquiry to verify what he was doing with all that money in a country at war. But then, as it often happens in Maltese affairs, nothing happened. Daphne Caruana Galizia too, the journalist murdered in an explosion the 16th October 2017, had investigated him. Writing about Grech, in 2015 Galizia had reconstructed the spiral of his business interests. One year ago, the businessman sold the motor fishing boat to a Libyan company that keeps using it on the route Valletta-Tripoli.

The Maltese government has not clarified how it plans to repay the private ships to which it asks for cumbersome changes of route to push migrants back to Libya. In the past few days, when the Maltese Foreign Minister Evarist Bartolo asked Europe 100 million euros to pay to Libya, a Maltese ship sent by the government arrived in Tripoli. It transported 30 tonnes of food and water “as part of humanitarian aids for migrants”. Those migrants have meanwhile gone back to the abuses of Libyan camps, thanks to European countries’ “rescue” and their bouncing back of responsibilities.