+++ About 350 counted fatalities in the central Mediterranean this year +++ Despite Criminalisation, Search and Rescue NGOs continue +++ Refoulements to Libya by state and commercial actors +++ From the Sea to the City: intensified co-operation toward corridors of Solidarity +++ More boats from Libya reach European SAR zones independently +++ The Tenacity of Migrant Struggles at Sea +++

Introduction

“It is so fucking inhumane what they are doing with us. We are here in the sea for more than a day now. They came with airplanes helicopters and everything. They know where we are and they just wait for the Libyans to come tomorrow to pick our corpses. Those who will still be alive will maybe then also go into the water because they want better to die then to go back to Libya. Why can’t they let any fisherboat save us and then at least to avoid people to die. They can bring us to whatever shitty prison. But this situation here is so inhuman you cannot imagine how we suffer.” (Man who called the Alarm Phone on May 29/30, from a boat in the central Mediterranean Sea. Eventually, he and about 100 others were rescued to Italy where survivors said that some had not survived their journey)[1]

Over the past three and a half months, the period of time covered by this new Alarm Phone regional analysis of developments in the central Mediterranean, the Alarm Phone was alerted to 24 distress situations in that region, involving over 1,700 people. Nine of these boats were returned, or presumably returned, to Libya. Seven were rescued to Malta and four to Italy. One boat was intercepted by the Tunisian coastguards. The fate of three boats remains unknown. Until 30 June 2019, according to UNHCR statistics, about 3,800 people have arrived in Europe via the central Mediterranean route. About 350 people have died in the central Mediterranean – or, rather, these fatalities have been officially recorded as the real figure will be substantially higher. For example, on April 1, the Alarm Phone was alerted to a boat carrying approximately 50 people and although Sea-Eye’s rescue vessel Alan Kurdi searched for the boat, the people were never found.[2] On April 10, people in distress told us that eight people had gone overboard – we don’t know what happened to them.[3] On May 10, when a boat coming from Libya capsized off the coast of Tunisia, it was estimated that about 70 people had died, but there could have been more fatalities. The 16 survivors were rescued by Tunisian fishermen and brought to Tunisia.[4]

This Alarm Phone regional analysis focuses on four main topics. It first highlights ongoing rescue missions by NGOs at sea, despite attempts of Italian and European authorities to undermining them by politically delegitimising and criminalising their efforts. It then turns to the interception and refoulement industry off the coast of Libya and Tunisia, where the return of escaping migrant travellers is often carried out by the so-called Libyan coastguards or merchant vessels and orchestrated by European forces, increasingly so from the air. Our analysis then moves to emergent coalitions of solidarity: In Naples, humanitarian rescuers, civil society organisations, representatives of municipalities, and activist groups met on June 20-21 under the slogan “From the Sea to the City”. The final section highlights the struggles of migrant travellers themselves, who are not passive victims but the central protagonists of their migration projects who enact their freedom of movement when they try to cross the dangerous Mediterranean Sea.

I. Non-Governmental Rescues Continue despite Criminalisation

Unwilling to accept the rising death toll at sea, search and rescue (SAR) NGOs have bravely returned to the death-zone off the coast of Libya. They do so despite all attempts to criminalise and delegitimise their humanitarian work, such as through the new Italian security decree that could fine NGOs with up to €50,000 for bringing rescued migrants to Italy.[5]

On March 18, the Italian Mare Jonio rescued 49 people “from shipwreck and from the risk to be captured and taken back to suffer again the tortures and horrors from which they were fleeing”.[6] They were disembarked in Lampedusa, where the rescued proclaimed “liberté, liberté” upon arrival.[7]

On April 3, Sea-Eye’s Alan Kurdi rescued a group of 64 people, including 10 women, 5 children, and 1 infant, who had called the Alarm Phone when in distress.[8] After yet another inhumane stand-off which lasted 10 days, the people were disembarked and brought to Malta.

On May 9, Mare Jonio rescued 29 migrant travellers, including an infant and three women, one of whom was pregnant, in distress in international waters – and disembarked them in Lampedusa the day after, where the rescue vessel was seized by authorities and captain and head of mission placed under investigation.[9]

On May 15, Sea-Watch 3 rescued 65 people after the civil aircraft Colibri had spotted the boat 30 nautical miles off Libya and disembarked them in Lampedusa, where the rescue boat was temporarily seized but freed in early June.[10]

On June 12, during Sea-Watch’s next mission, they rescued 53 people in international waters, about 47 nautical miles off Zawiya, Libya. The so-called Libyan coastguards assigned Sea-Watch 3 a port in Libya, but, of course, Sea-Watch directed itself north, to the closest port of safety. Yet another stand-off ensued, for 17 days, with more and more migrants having to be disembarked to Lampedusa due to medical emergencies.[11] With the remaining guests on board requiring immediate medical attention, Sea-Watch 3’s captain Carola Rackete courageously docked at the port of Lampedusa and was subsequently arrested, on June 29. An unprecedented wave of solidarity with the captain is unfolding throughout Europe and led to her release.[12]

On June 30, Proactiva Open Arms detected a boat off the coast of Libya that carried 55 people, including several infants.[13] They escorted the boat until Italian authorities took the distressed travellers on board and brought them to Italy. Despite all attempts to criminalise them, rescue NGOs are not giving up. Currently, Mediterranea’s Alex and Sea-Eye’s Alan Kurdi are on SAR missions near the Libyan death-zone.

II. The European Interception and Refoulement Industry

European attempts to prevent NGOs from rescuing coincide with attempts to bolster the so-called Libyan coastguards and increase their interception capacity. Over the past three and a half months, the Alarm Phone had to directly witness several of these cruel interceptions at sea, often orchestrated by European and Italian authorities.[14] According to the UNHCR, until 20 June this year, over 3,000 people were intercepted by the Libyan authorities. Through these measures, people are returned into conditions that are devastating and which have deteriorated once more after the beginning of March, when conflicts within Libya escalated further. According to several sources, the Libyans employed the patrol boats that had been donated by Italy not only for migrant interceptions, but also in ongoing war efforts in Libya.[15] Migrants trapped in horrific detention camps have reported being left in confinement without access to water, food, electricity and medical care, and several individuals were wounded when militias entered the detention camp in Qasr bin Ghashir. Whenever people call the Alarm Phone in distress in the central Mediterranean, they plead to not be returned into these conditions.

European Aerial Surveillance and Non-Assistance

Often, the so-called Libyan coastguards are instructed to intercept migrant boats by their European allies. Although the EU military operation Eunavfor Med/Sophia withdrew its maritime assets, its mission has been extended until September 2019 and its aerial surveillance capacities have increased.[16] The idea is to detect migrant boats earlier from the air so that they can be intercepted rapidly by Libyan allies.[17] To that end, and given the well-documented incompetence and lack of capacity of the Libyan authorities, operation Eunavfor Med has further attempted to strengthen the Libyan coastguard and navy even though they do not comply with international SAR conventions. That reinforced aerial surveillance has become integral part of the refoulement industry was documented by the Alarm Phone, for example on April 10.[18]

On that day, 20 people in distress contacted us after having left from Abu Khammash/Libya. They stated that eight people had gone overboard. Despite obtaining their GPS position and the boat being spotted by the Moonbird aircraft, European coastguards refused to conduct a rescue operation. A European military airplane even dropped a smoke can near the migrant boat in order to signal its location for refoulement by the so-called Libyan coastguards and the people were later returned to Libya. A few weeks later, on May 2, Mediterranea’s Mare Jonio witnessed how an aircraft of the Armed Forces of Malta guided a vessel of the so-called Libyan coastguards to the location of a migrant boat in distress in international waters. The migrants were intercepted and brought back to Libya.[19]

Increasingly, and as is desired by European governments and military operations such as Eunavfor Med, European assets at sea non-assist migrant boats in order to wait for Libyan authorities to arrive at the scene and return the migrants to Libya. On May 23, for example, the Alarm Phone was informed by a non-governmental reconnaissance aircraft that the Italian navy vessel P492 was nearby a boat in distress carrying about 80-90 people but decided not to intervene even though two tubes of the boat were deflating and people already in the water.[20] After several hours, the Libyan authorities arrived and returned the people to Libya.

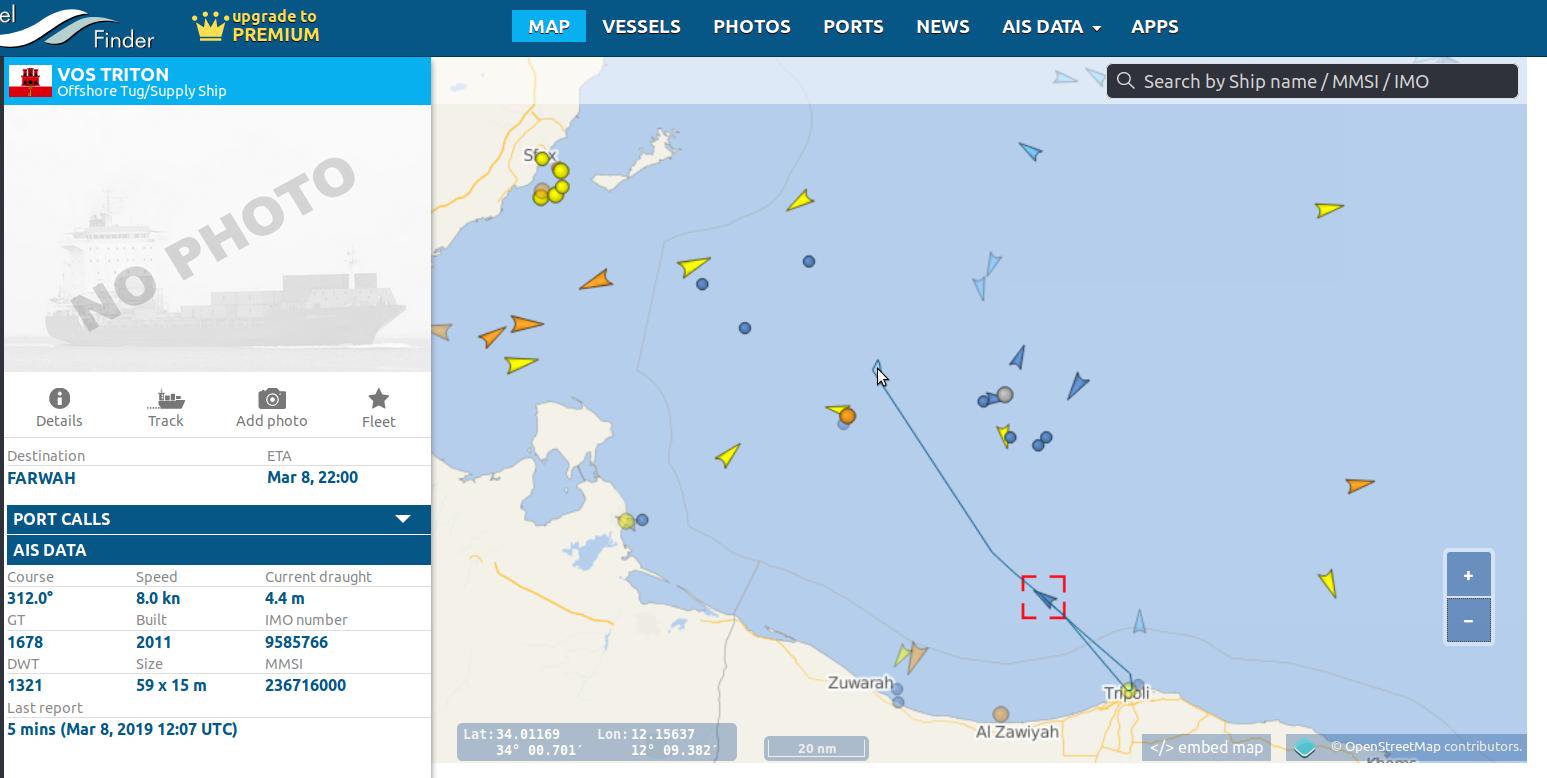

Merchant vessels as (involuntary) Partners in the Refoulement Industry

Merchant vessels are increasingly becoming a part of this refoulement system, as the Alarm Phone has documented several times before.[21] On March 8 the supply vessel Vos Triton under the flag of Gibraltar rescued 54 migrants in international waters and returned them to Libya.

Only a few weeks later, on March 26, the merchant vessel ElHiblu1 rescued 108 migrants in international waters and sought to return them back to Libya. The migrants, however, realised what was going on and courageously protested their return. They were able to have the ElHiblu1 redirect north, to Malta, where they were disembarked and some arrested (see below).[22] When commercial actors conduct rescues, they often face pressure by European states and coastguards to disembark the rescued in northern Africa, as highlighted in the following section.

Offshore Prisons

The European refoulement industry has consequences not only for Libya but also for other north African countries. When a boat with 75 migrants on board was ignored by Malta and Italy despite its distress, the crew of the tug boat Maridive 601 carried out a rescue operation on May 31.[23]

Source: Forum Tunisien pour les Droits Economiques et Sociaux

Source: Forum Tunisien pour les Droits Economiques et Sociaux

With Tunisia unwilling to allow their disembarkation in the harbour of Zarzis, a stand-off on the southern side of the Mediterranean ensued. For nearly three weeks, the migrants had to survive on board in inhumane conditions – food and water were scarce, scabies spread, and medical care for the injured and sick was inadequate. The migrants, the majority from Bangladesh, staged a protest on board, demanding to be brought to Europe “We don’t need food, we don’t need to stay here, we want to [go to] Europe!”[24].

Source: Forum Tunisien pour les Droits Economiques et Sociaux

Source: Forum Tunisien pour les Droits Economiques et Sociaux

The governor of Medenine stated that the 75 were only allowed to be disembarked in Tunisia if they were all immediately deported to home countries.[25] The Bangladeshi embassy’s envoy threatened the migrants with the withdrawal of food and water, were they to refuse to agree to their return to Bangladesh. When they were eventually disembarked, on June 18, they were brought to a centre in Tunis, from where several groups of Bangladeshi migrants were then deported over the next days, including many minors. These deportations were facilitated by the IOM. Contrary to what the IOM suggested, the migrants and their relatives told the Alarm Phone and the Guardian that these returns to Bangladesh had not been voluntary – none of them had wanted to return to the place they had risked their lives to escape from.[26] Currently, only some of the 64 Bangladeshi migrants remain in Tunis.

This case shows once more why Tunisia cannot be considered a ‘place of safety’. Moreover, it shows how merchant vessels can turn into temporary offshore migrant holding facilities until deportations are arranged. With vessels turning from places of rescue into swimming prisons near the north African shore, we seem to move a step further toward the proposal for floating hotspots far away from European territory, which was put forward by Italy in 2016.[27] For many years now, the EU and its member states are working hard to stop migrants already before they can reach European territorial waters. Last year, the plan was floated to install disembarkation platforms and camps run by EU authorities in several African countries.[28] As none of the African countries accepted the proposal, the EU and its member states are pursuing informal and bilateral agreements with individual countries to have them control migration flows and accept the return of migrants.[29]

‘Humanitarian’ Deportation

As in the Maridive 601 case, we see how international organisations such as the IOM and the UNHCR play a dubious role in the governance of migrants in northern Africa and elsewhere. Though repeatedly expressing their deep concern about the horrific situation for precarious migrants in Libya and the lethal rescue gap in the central Mediterranean, they never criticise the structural forms of violence that the European border and deportation regime embodies.[30]

In fact, the IOM in particular is an integral part of this border regime, though declaring itself as a humanitarian actor that cares for the rights and well-being of those intercepted in the Mediterranean and returned to Libya. Besides maintaining migrant camps in Libya, the IOM is promoting and executing the seemingly more humane ‘voluntary returns’ of migrants from Libya and elsewhere to countries of departure or transit, such as Niger.[31] For many, such as the Bangladeshi migrants from the Maridive 601 case, agreements to return are made under IOM pressure, with few to no other options being available. In Tunisia, the situation in the UNHCR run centre in Medenine has further deteriorated, with migrants protesting the conditions therein and demanding to be resettled to Europe. One person from Eritrea died there due to a lack of access to health care and one minor tried to commit suicide – he is still detained in Algeria after he escaped from Tunisia.[32] Some even leave Tunisia and return to Libya to try once more to cross the Mediterranean and reach Europe.

III. From the Sea to the City

While Sea-Watch 3 was still at sea, prevented from entering Lampedusa port, humanitarian rescue NGOs, civil society organisations, representatives of municipalities, and activist groups met in Naples on June 20-21 as the ‘Palermo Charter Process Platform’. We composed a statement, entitled “From Palermo and Barcelona to Naples: For the Right to Mobility and the Right to Rescue!” It says:

Humanitarian rescue NGOs, civil society organisations and activist groups, including Sea-Watch, Alarm Phone, Mediterranea, Seebrücke, Aita Mari, Jugend Rettet, Borderline Europe, Inura, Open Arms, and Welcome to Europe, as well as representatives of several European cities and municipalities, including Naples and Barcelona, have come together to work toward a collective European and Mediterranean initiative. Our movement was born in Palermo in 2018 and in the spirit of the Charter of Palermo, with its central demand for the right of mobility. Our slogan is: “From the Sea to the Cities!” …Over the past two days we have strengthened the collaboration between humanitarian rescue NGOs, civil society organisations, activist groups and city administrators. Our main aim is to join together in the struggle against the mass dying in the Mediterranean Sea. Those rescued at sea must be brought to safe harbours and be allowed to live freely and in dignity in European cities.[33]

Together we worked on two important issues: First, we strengthened the cooperation between the various actors engaging in SAR operations at sea. This is crucial in light of the fact that European governments and institutions, as well as Libya, have transformed the SAR zone off the coast of Libya into a borderzone. Here, rescue is not the primary imperative anymore but deterrence, even at the cost of human lives. European coastguards, such as those in Italy and Malta are not living up to their original mandate and are turning into simple operational centres that forward distress calls to the so-called Libyan forces that would then return those escaping to Libya’s detention camps. Over the past weeks, non-governmental cooperation at sea – from receiving phone calls from the distressed, to spotting them from the air, or rescuing them at sea – has already proven to be effective and thus needs to be further developed and strengthened.

Second, we worked toward a ‘transnational board of Solidarity Cities’ in order to foster exchanges and co-operations also on land. All over Europe, mayors and municipalities have signalled their willingness to welcome migrant travellers and have spoken out against inhumane migration policies at sea and the criminalisation of rescue. The Italian mayors of Palermo and Naples have been at the forefront of the struggle against the closing of safe ports. Also in Germany, municipalities are becoming increasingly vocal. In June, a large meeting took place in the town-hall of Berlin, where 13 municipalities built a new alliance of ‘cities of save harbours’, ready to welcome those rescued at sea. More coordination with cities in Spain, Greece, France, Netherlands, Switzerland and elsewhere is possible and necessary to create and amplify pressure from below for an Europe-wide reception programme involving receptive cities.

IV. Migrant Struggles at Sea

Despite the many ways in which Europe securitises its borders, people continue to struggle to move, and some still succeed in reaching Europe by boat. They actively seek out new routes and deploy a great diversity of tactics to circumvent Europe’s deterrence apparatus. And, of course, smugglers also adapt to changing developments in the Mediterranean. Over the past months, we have witnessed different struggles for freedom that play out in the Mediterranean. We want to highlight three important developments that we will briefly discuss in turn: First, we have seen how more boats than before seem able to reach European SAR zones, of course also due to improving weather conditions. Second, an increasing number of boats have gone beyond SAR zones and reached Italy or Malta independently – cases that go largely unreported in the international media. Third, migrants at sea have launched protests in order to avoid being returned to Libya – in the case of the El Hiblu1, they succeeded.

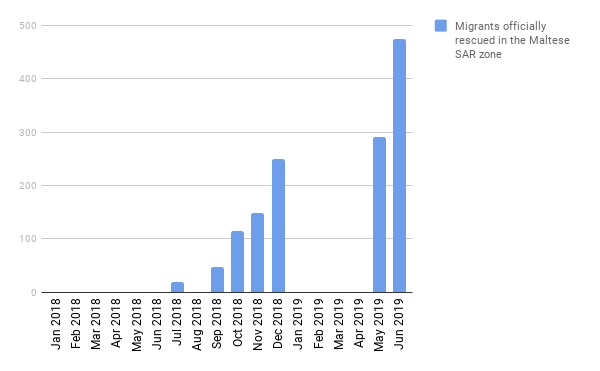

Migrant Boats in the Maltese SAR Zone

Since the end of May, there has been a market increase in migrant boats entering the Maltese SAR zone. It shows that those fleeing are aware that they have to bridge much longer distances to avoid being the intercepted back to Libya. On May 24, for example, the Armed Forces of Malta rescued 216 people from two rubber boats that had entered the Maltese SAR zone.[34] Ten days later, even more boats reached this SAR zones – 370 people were rescued to Malta between June 5 and 6.[35] Due to a lack of public information and data on where precisely migrant boats were rescued, it is difficult to precisely document how many had reached the Maltese SAR zone. However, the below chart indicates that the number of boats officially rescued in the Maltese SAR has substantially increased over May and June.

Source: Borderline Europe

The Alarm Phone directly engaged in distress situations in the Maltese SAR zone, for example on June 22 when people on a rubber dinghy reached out to us. When they passed on their GPS position, it was clear that they had reached the Maltese SAR zone and so we promptly informed the Maltese authorities. Though a cargo vessel was in the vicinity of this migrant boat, it did not intervene to rescue the people in need. During our contact with the people, we were impressed by their resilience and ability to remain calm and support one another during this challenging situation. In the early evening, our contact to the people, some of whom were from Pakistan, Egypt, Sudan, and Syria, broke off. Finally, after over seven hours after being informed, RCC Malta coordinated a rescue operation and the people were brought to Malta.

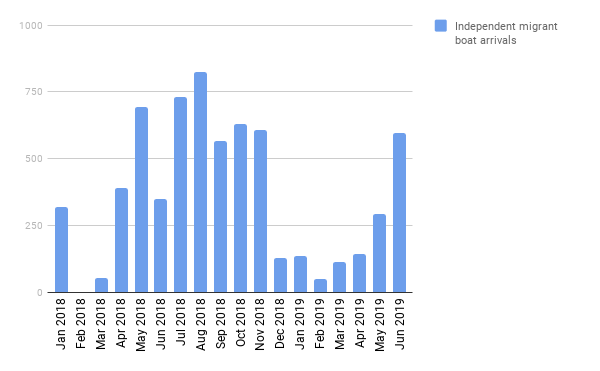

Independent Migrant Arrivals in Italy and Malta

Over the past months, more migrant boats have reached Italian and Maltese shores independently. Following some estimates, there were 115 people who reached Europe in this way in March, 142 in April, 295 in May and even 596 in June – this means that, over the past four months, a total of 1148 people reached Europe by boat without having to be rescued at sea.[36] Even though these figures are lower than last year, there has been a continuous increase since February 2019. We also assume that these numbers are not complete and that there are still unnoticed arrivals along the coasts of Italy and Malta.

Though there are also larger boats among them, the majority of boats that make it to Italian or Maltese shores independently are relatively small – carrying often between five and 30 individuals. The vast majority of these boats started from Libya or Tunisia, and only a few from Turkey (126 people left from Turkey in June and reached Italy). Types of boats vary, including rubber dinghies, wooden boats, fibre boats and even sailing boats.[37] These arrivals demonstrate that the European border remains porous, with migration finding its way even in some of the most difficult circumstances.

Migrant Protest against Refoulement

Migrant struggles at sea play out also in other ways, as the remarkable case of the ElHiblu1 shows. On March 27, the Turkish tanker ElHiblu1 had rescued 108 migrants from distress at sea. Its captain was instructed by a European navy air asset to return the rescued to Libya. When the migrants realised that they were about to be returned to the inhumane centres in Libya, they started to protest on board, forcing the captain to turn back north and direct toward Malta. The dominant discourse in the European media was shaped by a tweet by Italy’s right-wing minister of the interior, Salvini, who characterised the migrant protest as an instance of pirates hijacking a cargo boat.[38] After disembarkation in Malta, three teenagers aged 15, 16 and 19 were arrested. For their heroic protest they face imprisonment.[39]

The trial of the three teenagers will send an important message, similar to the trial of Ibrahim Tijani Bushara and Ibrahim Amid, who were charged before the Trapani Court after they were rescued in July 2018 together with 65 others by the cargo boat Vos Thalassa. Similar to the ElHiblu1 case, when they realised that they would be returned to Libya, they persuaded the captain of Vos Thalassa to move to a safe port in Europe. The court decided that the accused had acted in self-defence.[40] This verdict set an important message and precedent, confirming the right to protest against being illegally refouled back to Libya.

The Alarm Phone will continue in its support of these disobedient movements in the Mediterranean. We will not give up but continue in our struggle against the criminalisation of migration and sea rescue, as well as the security measures seeking to close down migration routes which leads to so much suffering at European borders. With those on the move we will continue to build bridges across barriers and spaces in society where we can live in freedom and dignity together.

Footnotes

[1] http://watchthemed.net/index.php/reports/view/1231;

see also: https://theintercept.com/2019/06/09/europe-migrants-mediterranean-rescues/

[2] https://twitter.com/alarm_phone/status/1112982814549520386

[3] http://watchthemed.net/reports/view/1184

[4] https://twitter.com/alarm_phone/status/1126823416714100737

[5] https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/jun/15/italy-adopts-decree-that-could-fine-migrant-rescue-ngo-aid-up-to-50000; https://twitter.com/seawatch_intl?lang=de; https://www.timesofmalta.com/articles/view/20190514/local/lifeline-captain-fined-10000-over-migrant-rescue-vessel-registration.709936

[6] https://mediterranearescue.org/en/news-en/the-mare-jonio-rescued-49-people-from-a-shipwreck-now-italy-must-indicate-a-safe-haven/

[7] http://www.ansa.it/english/news/2019/03/19/mare-ionio-migrants-disembark-at-lampedusa_c9f84431-f42e-40f7-a65a-b9544683a742.html

[8] https://twitter.com/alarm_phone/status/1113453642504445952

[9] https://twitter.com/rescuemed/status/1126540668351000577?lang=en

[10] https://twitter.com/seawatch_intl/status/1128656505362878466

[11] https://sea-watch.org/sea-watch-fordert-anlandung-43-geretteten-weltfluechtlingstag/

[12] https://twitter.com/alarm_phone/status/1144954941485830145

[13] https://www.elperiodico.com/es/internacional/20190630/open-arms-rescata-40-personas-navega-hacia-lampedusa-7529531

[14] https://mediterranearescue.org/news/documento-esclusivo-sulle-comunicazioni-tra-litalia-e-la-cosiddetta-guardia-costiera-libica/

[15] https://www.avvenire.it/attualita/pagine/libia-nessuno-pattuglia-mare-sar

[16] https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2019/03/29/eunavfor-med-operation-sophia-mandate-extended-until-30-september-2019/

[17] https://theconversation.com/eu-sued-at-international-criminal-court-over-mediterranean-migration-policy-as-more-die-at-sea-118223

[18] http://www.watchthemed.net/index.php/reports/view/1184

[19] https://www.thenational.ae/world/europe/malta-denounced-after-assisting-libyan-coastguard-to-intercept-migrant-boat-1.856853, https://mediterranearescue.org/en/news-en/breaking-news-from-mare-jonio-engaged-in-patrolling-and-monitoring-operations-in-the-central-mediterranean/

[20] https://twitter.com/alarm_phone/status/1131570709774446593

[21] http://watchthemed.net/reports/view/1135l; According to the Geneva Convention, vessels flying a EU flag have to disembark rescued people at ports of safety – Article 33(1) of the 1951 Convention. https://www.unhcr.org/4d9486929.pdf

[22] https://theglobepost.com/2019/04/03/migrants-pirates-identities/

[23] https://alarmphone.org/en/2019/06/03/the-survivors-on-maridive-601-must-disembark-solidarity-cities-in-europe-are-willing-to-welcome-them/?post_type_release_type=post

[24] https://www.facebook.com/293356094052952/posts/2246380565417152/

[25] https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2019/jun/19/migrants-stranded-at-sea-for-three-weeks-now-face-deportation-aid-groups-warn-tunisia

[26] https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/jun/25/bangladeshi-migrants-in-tunisia-forced-to-return-home-aid-groups-claim

[27] https://www.ecre.org/italys-proposed-idea-of-hotspots-at-sea-is-unlawful-says-asgi/

[28] https://openmediahub.com/2018/07/25/eu-unveils-details-on-the-new-migration-facilities-in-africa/

[29] https://taz.de/Aus-Le-Monde-diplomatique/!5602720/

[30] Disturbing videos as the one from Eritrean refugees detained in Zintan are available internationally: https://www.channel4.com/news/starvation-disease-and-death-at-libya-migrant-detention-centre

[31] https://reliefweb.int/report/libya/unhcr-update-libya-28-june-2019: 710 migrants were returned to Niger.

[32] https://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/features/driven-suicide-tunisia-unhcr-refugee-shelter-190319052430125.html

[33] https://alarmphone.org/en/2019/06/22/from-palermo-and-barcelona-to-naples-for-the-right-to-mobility-and-the-right-to-rescue/?post_type_release_type=post

[34] http://www.independent.com.mt/articles/2019-05-25/local-news/Armed-Forces-of-Malta-rescue-216-migrants-6736208630

[35] https://www.timesofmalta.com/articles/view/20190605/local/migrants-rescued-by-afm.711971

[36] See for example: https://www.firenzepost.it/2019/05/30/lampedusa-proseguono-gli-sbarchi-di-migranti-45-lasciati-a-terra-da-un-peschereccio/

[37] http://www.ansa.it/sito/notizie/topnews/2019/06/02/migranti-in-70-sbarcano-nel-tarantino_faefa064-2d2c-40c2-9baf-c65837b92d96.html, http://www.ansa.it/sito/notizie/topnews/2019/06/03/sbarco-in-calabria-soccorsi-30-migranti_36b63087-e6de-40fa-b30a-a9394e4f802d.html, https://www.fanpage.it/73-migranti-salvati-in-mare-riportati-nelle-carceri-libiche-nuovo-sbarco-a-lampedusa/ ; http://www.ansa.it/sito/notizie/topnews/2019/06/03/migrantiin-21-sbarcano-nel-sud-sardegna_41b40f20-389d-4508-bf1d-70e11f7286e4.html

[38] https://www.gov.mt/en/Government/DOI/Press%20Releases/Pages/2019/March/28/pr190637.aspx; https://www.spiegel.de/politik/ausland/fluechtlinge-im-mittelmeer-vor-libyen-maltas-marine-uebernimmt-kontrolle-auf-tanker-elhiblu-i-a-1260042.html

[39] https://www.tagesschau.de/ausland/malta-migranten-angeklagt-101.html

[40]https://www.ilfattoquotidiano.it/2019/05/24/migranti-che-dirottarono-nave-assolti-per-legittima-difesa-ora-ricorso-a-corte-strasburgo-contro-salvini-e-toninelli/5204596/