Navigating the bureaucratic obstacles of obtaining documents – an endless mission. Source: Alarm Phone

1. Introduction

While we were looking back at another eventful spring and summer on the migration routes in Western Med and on the Atlantic Route, international attention suddenly turned its eyes on Morocco: The severe Oukaïmedene or Marrakech-Safi earthquake and its aftershocks which struck Western Morocco on September 8, 2023, killed nearly 3,000 people and left at least 5-6,000 people injured. Our thoughts are with the victims, and especially with the friends of our Alarm Phone members in the Western Mediterranean and Atlantic region who are directly affected by the aftermath of this catastrophe.

For many people, this earthquake has exacerbated what were already difficult living conditions in Morocco (poverty, political repression, lack of opportunities). While international attention is very quick to move on, the disenfranchisement of many people, in particular people on the move, continues.

This analysis highlights one particular obstacle to societal participation for Black Africans living in Morocco: their legal status and very limited access to regularisation. It documents the large gaps between theory (a supposedly “modern” migration policy) and the reality people on the move experience across different regions in Morocco (see chapters 3.1.-3.3) and in Algeria (see chapter 4). Even when people have crossed the Mediterranean (or the Atlantic), they face severe challenges in Spain when it comes to obtaining legal status (see chapter 5).

The analysis also documents the involvement of Alarm Phone in the region (see chapter 2), recent developments on the different migration routes (e.g. the Atlantic, the Alboran Sea) and the huge number of shipwrecks and deaths (see chapter 6).

The issue of regularisation in Morocco

A full ten years ago, Morocco carried out a major reform of immigration law. On 11 November 2013, the government announced a far-reaching exceptional regularisation campaign for the year 2014 which would enable many thousands of people (mostly people on the move from other African countries) to regularise their status. The campaign was repeated in 2017, altogether approximately 50,000 residence permits (cartes de séjour) were granted. Many of the people regularised in these campaigns had, given the lack of regular routes, entered Morocco “unlawfully” (an act criminalised by Law 02-03, adopted in 2003). These changes in Moroccan migration policy did have a positive impact on the lives of many people on the move – albeit in a rather limited way. Although many people now theoretically had the right to work, jobs remained scarce, and although people should now have been protected from arbitrary detention and forced displacement, such pratices continued unabashedly.

Many people on the move (and this perspective is also shared by some migration scholars) remain very sceptical about these reforms: “For me, these regularisation campaigns are a trap, because once migrants obtained the first residence permit, the authorities made the renewal very complicated, asking for documents they knew they migrants did not have,” explains L. from Alarm Phone Tanger.

The kingdom of Morocco used the regularisation campaign to present itself as a “modern” state, with a supposedly “humane” immigration law – an important gesture vis-à-vis Europe and the neighbouring African countries which emulate Western migration policies to a lesser extent. There was also broad suspicion that Morocco would use this campaign to gather information about the different migrant communities or that the campaign served to coopt NGOs more closely to the state. Indeed, it was NGOs which played a key role in helping migrants access the carte de séjour (residence permit).

Just as we can observe in many European countries, the Moroccan regularisation policies were never meant to actually put an end to a system of racist and classist oppression, it was never part of a wider strategy to actually offer opportunities for societal participation.

As the AMDH complained in 2022, the social and economic rights of migrants and asylum seekers are not implemented despite the adoption of a national strategy to ensure better integration and facilitating equal access to public services:

“[…] after nearly ten years, this strategy remains slow, limited, ineffective […] in its practical implementation. It seems to have been present, especially since its adoption, for the Moroccan State to take it into account in international forums without doing enough so, so that migrants and asylum-seekers can enjoy the rights endorsed by this ambitious strategy. The reality experienced by migrants and asylum seekers in different regions of Morocco refutes this;”

How to obtain asylum in Morocco – as far as the theory goes…

As the legal and institutional architecture of Morocco’s own asylum system is ostensibly still being put in place, asylum claims tend to first be handled by UNHCR where persons will be recognised as refugees or not by the international agency, according to their criteria for refugee status. This is based on the 1951 Geneva Convention. After obtaining UNHCR papers, people are sent to the Bureau des Réfugiés et des Apatrides (BRA) (Office of Refugees and Stateless People) in Rabat, part of the Ministère des Affaires étrangères et de la coopération (Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Cooperation). As stated in its foundational document, through the development of the Stratégie Nationale d’Immigration et d’Asile (National Immigration and Asylum Strategy), the BRA includes a number of government officials and ministry representatives. UNHCR refugees are required to attend one of their meetings in order to receive the UNHCR refugee card (which is only issued after a thorough investigation of the submitted documents). With the refugee card, they can then apply for residency. Some of the more stringent requirements will be waived and their application should be treated more favourably.

The following documents are required for all applications:

- A copy of the photo pages of the passport, including the pages bearing the entry stamp, and, depending on the country of origin, an entry visa

- 8 recent photos

- An official summary of the criminal record

- A medical certificate

- A birth certificate

Challenges in obtaining a residence permit: the reality of what people on the move experience

Of course, the above-stated process only applies to individuals who can obtain status as a refugee in the first place. However, this does not apply to the vast majority of people on the move. Their only ever opportunity to have access to papers were the regularisation campaigns in 2014 and 2017. Since then, people struggle with the renewal of their residence permit, and those having entered Morocco since 2018 do not have any prospects at all. In particular, since 2021 the new government has vowed to enforce an even stricter application of the legal consequences of the “unlawful” entry (law 02-03). This has made it far more difficult for many non-nationals to renew their residency cards.

The problem usually starts with the bureaucratic hurdles when applying for a residence permit. For many people it is very difficult to obtain the required extract from the criminal record as it has to be issued in the country of origin. The medical certificate must state that the person is not suffering from a contagious disease, a requirement which many people are unaware of. Furthermore. A tax stamp is required, although since 2013 the administration no longer accepts tax stamps but only cash (Senegalese, Tunisian and Algerian nationals are exempt from paying these taxes).

Presenting a birth certificate is also a major obstacle. Many people on the move do not have access to this document (or it was stolen from them), but the situation is particularly dramatic for new-born children. In some regions, hospitals regularly refuse to issue a birth certificate for a new-born if the parent(s) do(es) not present a passport – a practice that has no legal basis, but which effectively makes it impossible for many new-borns to have a birth certificate. As a consequence, they are then barred from vaccination, school and many other social services. These practices vary according to the region.

If a non-national plans to stay longer than the 90 days of the initial visa, they are required to apply for residency in the administrative district of their registered address. However, this seems to be even more difficult in certain regions than others. Applicants have reported that they are refused in some towns (e.g. Salé) while accepted in others (e.g. Rabat) with the same paperwork. Rumour has it that it is easier to regularise in the Oriental region (e.g. Oujda) than in Tangier-Tetouan-Al Hociema or in Rabat-Salé-Kénitra. It is not always clear why, sometimes it is due to the ignorance or malevolence of local authorities. These inconsistencies could signal administrative failures, uneven knowledge sharing and training, or a deliberate strategy to concentrate Black African migrants in certain regions of political and economic value to Morocco.

Additionally, many people without valid entry clearance to Morocco have been asked to leave the territory and re-enter legally in order to renew or regularise their status. This comes at great expense and, for many, at great risk. Many of those who have done so are often then denied visas to re-enter Morocco. Some then re-enter illegally, returning to same juridical limbo, after having lost a lot of time and money.

Moreover, even with a valid passport and right of entry, a residence permit is often required for both housing and employment contracts – while at the same time, housing and employment contracts are often required to regularise residency, thereby creating a catch-22 scenario. In addition, non-nationals face discriminatory laws which demand an employer to give preference to a Moroccan worker of a non-national employee.

However, there are ways around these barriers. Landlords and employers can support the residency application of tenants and employees, but this costs time and money. Moreover, many irregularised people on the move will, in any event, pay for a place to sleep and work for minimal fees, given a lack of other options. People are racially profiled as seeking to travel to Europe illegally, thus, legal and economic precaritisation is compounded by the constant political policing of their movements. As a result, landlords and employers generally have no incentive to go to the hassle and expense of assisting someone to sort out their residency status. As we have already demonstrated in past reports, the precarity contributes to the economic exploitation of people on the move.

R. from Alarm Phone Tiznit succintly sums how little the regularisation campaigns have improved the situation of people on the move in Morocco:

“The access to the residence permit remains very restrictive. This shows that the campaign is an illusion, it’s a fiasco. Even s3awhen regularised, many migrants still have difficulties in finding decent accommodation. They hardly have access to employment in the formal sector, instead, they face overly long working hours and low salaries.”

2. Sea crossings & Statistics

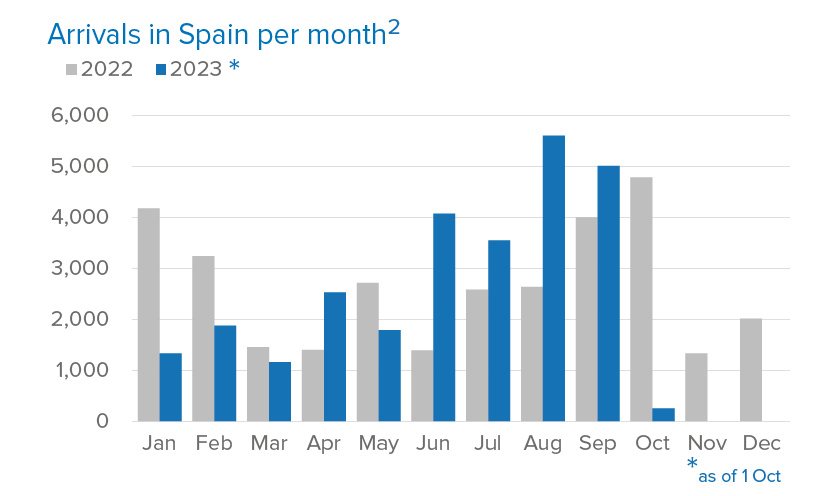

As of 01 October 2023, the UNHCR estimates that in this year 27,220 people arrived in Spanish territory, 15% more than in the same time period in 2022. Although there were significantly more arrivals in January and February 2022 than in the same time period in 2023, in the summer months of 2023, especially in August, nearly twice as many people arrived as in August 2022.

Figure 1: Arrivals in Spain per month. Source: UNHCR SPAIN Weekly snapshot – Week 39 (25 Sep-01 Oct 2023)

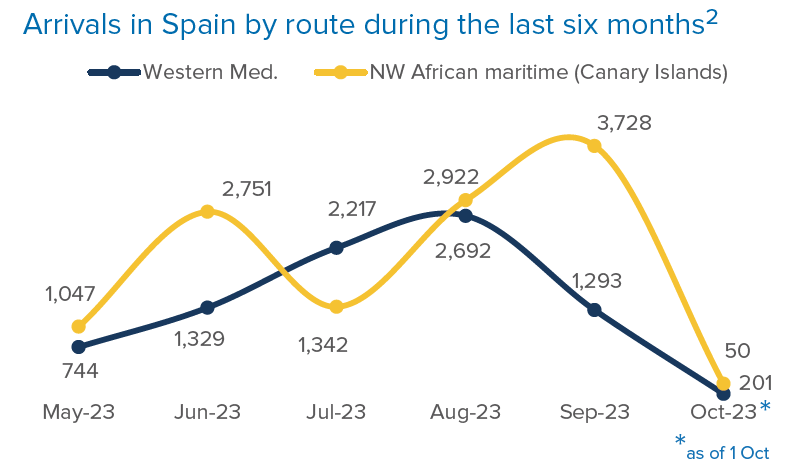

Most people chose to leave Morocco via the Atlantic Route (see chapter 3.1.) closely followed by a high number of departures in the Alboran Sea and the Strait (see chapter 3.2. and 3.3.)

Figure 2: Arrivals in Spain by route Source: UNHCR SPAIN Weekly snapshot – Week 39 (25 Sep-01 Oct 2023)

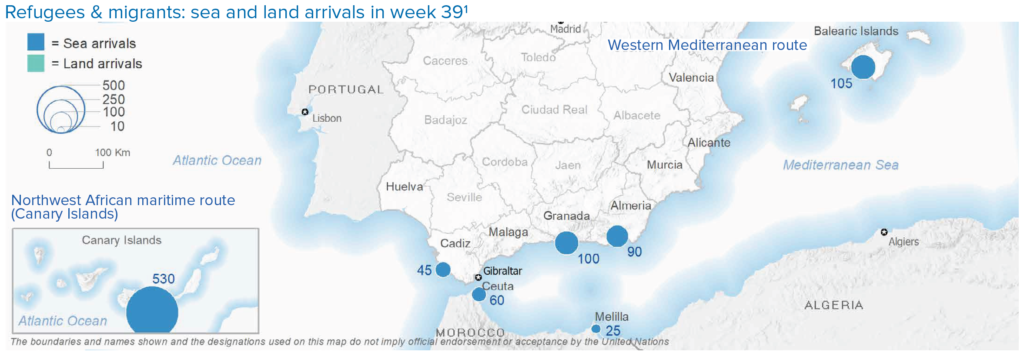

A particularly large number of arrivals was recorded in Almería, which might be related to more and more people choosing to leave from Algerian shores (see chapter 3.4).

Map of arrivals in Spain by land and sea Source: UNHCR SPAIN Weekly snapshot – Week 39 (25 Sep-01 Oct 2023)

These figures correspond with the overall number of Alarm Phone cases along the Western Mediterranean and Atlantic route. Since the beginning of this year, Alarm Phone was informed about 149 cases of people trying to cross the dangerous borders to Spain. In 64 cases, people on the move chose the Atlantic route, another 62 alerts came from the Alboran Sea or the Strait and 23 calls were received from people who had departed from Algeria. Compared to last year, the much higher number of alerts in the Alboran Sea is particularly striking.

According to the numbers given by the people who alerted Alarm Phone between March and September, the boats in this region were carrying at least 3,560 people. Out of the 122 cases, 49 boats were rescued by Salvamento Marítimo, 5 arrived by themselves to Spanish territory, 35 were brought back to Morocco by the Marine Royale and 4 returned by themselves. We are very worried about the 23 cases of which the fate of the people remains unclear. We are also sad and angry about the six shipwrecks we had to witness, amounting to more than 148 missing and at least 104 people dead, many of whom were between the ages of 10 to 25. Alarm Phone was informed about many more deaths at sea, as one can read in more detail in chapter 5. Our thoughts are with the friends and relatives of Mohamed, Ayoub, Tounsi, Hamza, Annas, Youssef, Nabil, Azzedine, Souhir and so many others, who lost their lives at the EU’s deadly (sea) borders.

3. News from the Regions in Morocco

3.1. The Atlantic Route

Since March 2023, Alarm Phone supported 49 boats on the Atlantic route. During these months, we witnessed some horrific shipwrecks and, once again, many boats remain missing. On 15 June, for example, Alarm Phone was called by relatives worrying about a boat that had left Agadir on 11 June with 51 people on board. This boat went missing. We wish to express our profound sorrow to the relatives of the victims. The journeys undertaken from southern Morocco often result in a shipwreck due to the rubber boats which are used on that route being particularly dangerous. On 26 June, we were informed about a boat with 55 people that had left Guelmim. We later found out that the rubber boat had capsized. By sheer luck, four people made it back to Moroccan shores. The other 51 perished. Another deadly shipwreck involving a rubber boat occurred in mid-September when 13 people fell overboard. 38 were rescued by the Spanish coastguard.

One shipwreck has received particular attention, because it highlights the ongoing practice of delegating responsibility for a rescue operation to the Moroccan authorities. On 20 June, Alarm Phone was alerted to a boat with 61 people in urgent distress. We immediately informed the Spanish authorities, and the GPS position we received showed the boat in the area that Salvamento Maritimo is responsible for (as shown on their homepage), but which is also claimed by Morocco due to its occupation of Western Sahara. Although a Spanish rescue asset was only one hour away from the GPS position (albeit, with 63 other rescued people on board), the Moroccan authorities, in coordination with the Spanish authorities, took over responsibility for the rescue operation. The result of the delayed response of the Marine Royale: 37 people missing and only 24 survivors. As Alarm Phone, we have submitted our documentation to the Spanish Defensor del Pueblo (ombudsman), who opened an investigation shortly after the shipwreck. We are sad and outraged that this geopolitical power game has again cost the lives of people who have a right to migrate and the right to be rescued by a competent authority when in distress at sea.

Between June and September 2023, more than 70 boats from Senegal made it to the Canary Islands. Welcome! Source: AP Dakar

The biggest change on the Canary Island route that we have been able to observe since June is certainly the increase in departures from Senegal. Alarm Phone Dakar has listed approximately 70 boats that left from Senegal between early June and late September and which arrived in the Canary Islands . Overall they carried nearly 6000 passengers. However, some other boats were intercepted right away or went missing. For example, a boat with 38 survivors was found on Cape Verde on 16 August. There were also 7 dead bodies, but another 56 people are missing, presumed dead. When the Senegalese authorities decided to only repatriate the survivors and leave the dead behind, the families and friends in the village of Fas Boye revolted and were brutally silenced by the Senegalese police. A boat with 63 people left Rufisque (near Dakar) and capsized off the shores of the Sahara on 20 July. 18 people died. Another boat capsized off the shores of Dakar on 24 July, resulting in 16 deaths.

Concerning the big increase in departures from Senegal, S. from AP Dakar reports:

“The political situation in the country is getting catastrophic and causes demonstrations with many deaths and abusive detention. In addition to that, the visa policies [of the EU countries] make it very hard and arbitrary to obtain a visa. These are some of the reasons that push young people to leave the country, even if it means they have to embark on a very risky journey.”

However, the Senegalese government only reacts to this people’s movement with more repression, criminalisation and deterrence. On 23 July, they created an “Comité interministériel de lutte contre l’émigration clandestine” (Interministerial Committee for Combating Illegal Migration) and on 4 August, a big new office building was inaugurated to host the “Division de la police de l’air et des frontières” (Air and Border Police Division). Alarm Phone activist S. comments: “This is shameful. They are using these institutions to intimidate the population in Senegal.”

This revival of the Senegal route is reflected in the hightened numbers of arrivals compared to the previous year. While relatively few people arrived on the Canary Islands in the first months (around 3,500 people by mid-May), the figures for 1 October are already at 15,406 arrivals, which amounts to 24% more than in 2022 – as always, we are very happy for all those who survived the dangerous journey! In the first half of September alone, 3,100 people arrived to the Canary islands, with approximately two thirds of these boats being large wooden fisherboats (called “pirogue” in French, or “cayuco” in Spanish) from Senegal. Only very few boats make it to the Canaries from Mauritania (five boats this year) due to the close cooperation between the Mauritanian government and the Spanish authorities, for instance the Guardia Civil.

In late August, however, the Mauritanian authorities refused to play their role in a mass pushback by not accepting 168 people from Senegal who had been intercepted by the Spanish Guardia Civil off the coast of Mauritania. Consequently, the Guardia Civil then push-backed everybody to Senegal, despite resistance (e.g. hunger strikes) on board. On 22 September, another boat with 70 people was intercepted by the Mauritanian authorities. Members from Alarm Phone Mauritania confirm that 16 of the passengers are still in Noudhibou to receive medical treatment, but the other 54 were deported to Senegal via the Rosso border post.

The increase in arrivals again puts strain on the workers of the Spanish rescue agency Salvamento Marítimo. In mid-September, their ongoing demands for more hands on board were again rejected by the government which claims that there is currently no overload. Given the high numbers of arrivals (3,100 people in the first two weeks of September) we find this assessment somewhat cynical. As Alarm Phone, we fully support the demands by the CGT to equip the rescue vessels with a fifth crew member, to introduce a third rotating backup crew, as well as a crew permanently stationed on the Canary Islands.

The struggle with documents and legalisation

In the Sahara and in Morocco, like in all the other regions, people face serious discrimination because access to acceptable documentation is made so difficult. As B. from Alarm Phone Laayoune describes the situation:

“It’s is so difficult nowadays to renew the carte de séjour because of all the documents that are required to do so. Many people lost their job, especially as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. However, in Laayoune, the Moroccan authorities continue to carry out arbitrary arrests and ask for the residence permit, while knowing that migrants have not been able to obtain this document for quite a while now. It’s a cat-and-mouse game.”

Thanks to the pressure exerted by local associations, people with residence status are now usually exempted from raids, arrests and deportations, especially if they know and can defend their rights. However, according to estimates done by Alarm Phone, 80% of all Black people do not have a residence permit and are thus easy victims of these forms of violence and harassment.

Regarding children, hospitals in the Sahara and southern Morocco also pursue a policy of demanding documents from the parent for issuing birth certificates. Since the large majority of people on the move do not have such documents, around 70% of all their children currently do not have a birth certificate. This excludes them from a variety of social services, e.g. health care and vaccination, access to education and more.

On the Canary Islands, administrative procedures for obtaining documents can also be hampered by certain irregularities. People arriving on the more Western islands sometimes do not get properly registered in the (somewhat smaller) police stations and thus suffer from serious obstacles in the further course of their regularisation procedures.

3.2. Tangier, Street of Gibraltar & Ceuta

News from the region

Over recent months there has been a mass exodus of people seeking to travel to Europe from Tangier. They have left for Tunisia after a series of Bozas (successful crossings to Europe) from Tunisia to Italy. The EU has signed a new deal, valued at over €1,000m, with €105m specifically dedicated to assistance on stopping onwards migration to Europe. “They’ve [Tunisia’s] entered ‘the migration game’,” claims one AP Tanger activist.

The effects of this have been felt across Tangier. For example, there are fewer Black women begging at traffic lights. “Every day people are leaving to Tunisia”, a woman from Ivory Coast explains while begging. The population of neighbourhoods on the outskirts of the city, where Black people are known to live, suddenly diminished. “Everyone’s gone to Tunisia,” a Cameroonian resident exclaims, stretching out his arms in a near empty square between the houses, bustling only a day or two before.

In response, arrests and removal of Black Africans profiled as going to Europe has also gone down. “They often deport us towards Algeria, and Algeria is on the way to Tunisia, so they would be paying most of the transport for us,” one woman hoping to go to Europe jokes. “They are nervous about loosing their share of the migration flow,” a young man explains. “Now they are pushing you back into Morocco from near the Algerian border”, he claims. It could also be that authorities are concentrating on relief efforts following the earthquake that stretched across Morocco, but left Tangeir unscathed.

Nonetheless, according to evidence gathered by AMDH Nador, in the lead up to this exodus, another three people were killed by the authorities in their violent repression of an attempt to cross the border fences at Ceuta on 14 April 2023. Among those missing is Mamadou Aliou Diallo, a young man from Guinea who received a blow to the head. His friends wanted to save him, but were forced to save themselves when security forces arrived. It is not known what happened next to Mamadou, and whether anyone took him to hospital or not.

Issues around regularisation in Tanger

If you are Black and African, it is necessary to have a carte de séjour (and to carry it with you) to avoid routine police harassment and involuntary internal relocation to the South of the country from Tangier. Tangier is on the narrow Strait of Gibraltar and is typically understood as a zone of departures to Europe. However, housing and work contracts usually required for legal residency as a non-national in Morocco are hard to come by in Tangier. This is especially so for people who have arrived ‘irregularly’ (without state persmissions). Apart from highly qualified specialists, who mostly work in the city’s industrial zones, it is generally accepted that there is less work for non-nationals in Tangier than in the major cities of Casablanca and Rabat.

NGO services and support to regularise residency status and to integrate in the country also seem to be concentrated in Rabat, as part of a broader migration governance strategy. Nonetheless, there are drop in sessions offered for regularisation advice in Tangier, though usually only for persons with refugee status or who already possess the carte de séjour. Applications for refugee status are generally carried out in the UNHCR office in Rabat, though it is possible to begin the process in Tangier via UNHCR partners, such as OMDH, or during one of UNHCR’s tours of the country.

Enabled by blurred notions of legality, there are well-placed individuals who help migrants regularise their status. Like the migration routes out of the country, this is a business. It’s one that official associations cannot advise people on, even though it is often one of the most effective ways to regularise status. Often without clear guidance and with a legal process that is regularly changing, many undocumented Black Africans are particularly vulnerable to exploitation. Scams — conducted by Europeans, Moroccans, and other Black Africans — are commonplace, as the following example shows. One Alarm Phone member encountered a man who claimed to have an association and to be an expert on regularisation. After encouraging a group of undocumented women to send their paperwork to him, assuring them he could assist them through the process of getting a letter from their embassy as a perfectly legal substitute to a new requirement to have legally entered the country, he took their money. He then claimed that the women could pay off their debts by producing pornographic videos with him, which he then refused to pay them for. A group of people then self-organised an arrest of the man and organised support for the survivors of his attacks. The case was pursued by one of the women in question, the man was forced to return the money, and subsequently served a few months in prison.

3.3. Nador & Melilla

News from the region

Moroccan nationals continue to cross towards either Melilla or across the Alboran Sea to the Iberian peninsula, being forced to use channels and networks that were established mostly for trafficking hashish but are more and more facilitating the “burning” of the Spanish border. Six years after the crushing of the Hirak social uprisings, thousands of young people from the region have emigrated clandestinely, and by October 2023 alone more than 5,000 people had reached the coasts of southern Spain by boat this year.

Sea crossings take place on so-called ‘go-fast-boats’ that are referred to as ‘Narcolanchas’ in Spanish (in French ‘fantômes’: ‘ghost ships’), high-speed semi-rigid inflatable boats, that were actually banned in Spain by royal decree in 2018.

A so called ‘fantôme’, ‘go-fast’-boat, Source: AMDH Nador

AMDH Nador collected testimonies from people involved, who report that, in spite of the official ban, there is basically unrestricted access to the equipment needed for sea crossings in Spain. According to the reports, it is very easy to embark with the equipment and take it to Morocco. Once there, Moroccan harraga, the majority of whom are young, are picked up. The going rate for a berth is currently up to 110,000 MAD (~€10,000). The boat then ferries the harraga to the peninsula. This generally occurs without interference from either the Moroccan or Spanish authorities (Guardia Civil). On 27 and 28 August alone, 12 of these ‘Narcolanchas’, or “go-fast-boats”, arrived on the coast of Almería. They carried around 600 passengers. This rather costly option is out of reach of Black Africans, however, some Syrian and Bangladeshi nationals use this route. They have to even pay up to €13,000 (according to local sources). The price is very high, and AMDH assumes that the authorities are benefitting from this profitable business, as there is barely any interference. Arrests of some of the people in the trade do happen, as for example occurred on 02 August, but they are few and far between. AMDH also has this in testimony from a boat driver.

For the Black communities in the area, this is a price that most cannot afford. Sea crossings by sub-Saharan nationals are still close to stagnating. Though as the Atlantic route is so dangerous, many people come from Laayoune or Tan-Tan to the forests outside of Nador in the hope that crossings via Alboran Sea will resume. In the meantime, the only hope to reach Spain and the European Union is via the fences that separate the Spanish colonial city of Melilla from Moroccan territory. The fences have witnessed many violent and unlawful acts by both Moroccan and Spanish authorities over the past years. In the aftermath of the 24 June 2022, where a massacre that gained international attention was committed at this exact border zone (see: previous reports), the fences are being even further reinforced. €4.9 Million is being invested from the Spanish side.

“When it comes to poor migrants who want to jump the fence with Melilla, we’re ready to commit a massacre, and when it comes to migrants who pay 110,000 Dhs each to cross on board a ghost ship, we prefer to keep quiet.” (Source:AMDH Facebook post)

Having said that, the situation is not easy for Moroccan harraga trying to reach Spanish territory. In Nador, even Moroccan nationals are not exempt from the forced removals away from the border zone, as AMDH Nador observes:

“In front of the illegal detention center for minors in Béni Ensar, the deportation bus is ready to take away the Moroccan minors and young people arrested during the daily roundups in Béni Ensar. [These are] Brutal and inhumane deportations during which the minors are given only a piece of bread (half a Khobza) on a night-time journey of over 500 kms to be dumped in Casablanca. As if Nador isn’t part of Morocco. Our country, where a Moroccan citizen should be able to move freely and be wherever he wants to be.” (Source: AMDH Nador)

Deportation bus in front of the detention center for minors in Béni Ensar, Source: AMDH Nador

Not only young men leave Morocco, whole families try to leave and embark on the perilous journeys from Nador towards Melilla or mainland Spain. And it is not only the boat and weather conditions, but also the irresponsible engagement of authorities themselves that endanger lifes. One example took place on 15 May, when we were told that a boat carrying 13 people was pushed back towards Morocco by Guardia Civil naval assets, resulting in two passengers jumping into the sea. Another occured on 01 August, when a dinghy flipped because of the manoeuvres of the Guardia Civil and people had to be rescued by local citizens.

The reality of regularisation in the Nador region

Regularising your status in Nador is far form easy. Theoretically, people on the move can obtain the carte de séjour (residence permit) as in all other regions of the Moroccan state, but practically, the granting of this legal status in Nador is much more restricted than, for example, in Casablanca or Rabat. This is because of the proximity of Nador to the landborder with the Spanish enclave Melilla. Authorities try to prevent too many people on the move from staying in Nador. As so few people manage to get a carte de séjour (for example those that work with established associations), and even fewer manage to renew it, people on the move face major obstacles and dangers in this region. Without papers, there are very few work opportunities and limited access to housing, so people are forced to live precarious lives in makeshift camps in the forest around Nador. Violent raids, arbitrary arrests and frequent deportations to southern regions of Morocco are a subsequent norm.

To register with UNHCR as asylum seeker is a way people could, according to international law, use to protect themselves from such violent removals to the South. But unfortunatly we have seen that even people carrying the ‘refugee card’ have actually been pushed south. The security that the UNHCR document provides is in fact very limited. Moreover, it is not easy in the border city of Nador to obtain the UNHCR paper and eventually the refugee card. The communities on the move advise people who want to try that route to go to Oujda for that purpose instead.

4. Algeria: destination and transit country at the same time

Context: Algeria as a destination/transit country

Algeria is traditionally known as a country of emigration, overwhelmly to France and more recently to Spain and Canada. But since the late 1990s, the country has also been a major destination for thousands of people on the move, particularly from the Sahel and Western Africa regions. Algeria’s immense territory (more than 2.4 million km²) borders seven countries: Morocco and the Western Sahara to the West, Mali, Mauritania and Niger to the South and Libya and Tunisia to the East. Its coast stretches for about 1,000 kilometers along the Mediterranean and its land borders are more than 6,700 kilometers long.

As M. Saïb Musette and N. Khaled put it in their paper “L’Algérie, pays d’immigration?” (Algeria, a country of immigration?): “Sub-Saharan and Maghrebian border migrations are driven by geographical proximity, the history of the region’s communities and economic exchanges.”

In the last years, Algeria has also attracted people fleeing from war zones, such as Syrians who have been arriving in large numbers since 2012.

With regard to migration between Africa and Europe, Algeria occupies a key role. It is an immigration country for migrant workers from Western and Central Africa and the Sahel (particularly from Niger), but also an important transit country for people on the move, mostly from countries South of the Sahara, on their way to Europe.

For years, migrants from sub-Saharan Africa were in high demand in various sectors of the economy, as it was more profitable for companies to employ them than to hire local workers. These jobs in Algeria’s informal economy enabled people to earn the money that they needed to travel to Europe. After a few months or years, they would leave the country, via Libya or Morocco, and then make their way to the EU. But with the intensification of controls and the tightening of the border regime with Morocco, Tunisia and Libya (largely the result of the externalization of EU migration policies), countless people hoping to reach Europe have been forced to stay longer in the country.

Statuses and reality of living for people without residence permit in Algeria

a) The refugee status

According to UNHCR data, as of September 2021 about 98,000 recognised refugees lived in Algeria. 90,000 of those are Sahrawis from Western Sahara. In addition, as of mid-2021, 8,000 people, mainly from Syria, Mali, Palestine and Yemen, were recognised as refugees by UNHCR in Algeria.

Algerian laws are very vague when it comes to international refugee law and do not provide for a statutory right to asylum. In fact, the “UNHCR is the only point of contact in Algeria for refugees and asylum seekers“. Algerian authorities often grant residence permits to refugees on presentation of identification or status documents issued by the UNHCR. Refugees from Arab countries are favored over Black African refugees. With the latter, the authorities have adopted an increasingly arbitrary policy in recent years, as we have repeatedly documented in these reports. Since 2014, the Algerian state has expelled massive numbers of people recognised as refugees by the UNHCR or migrant workers holding valid visas. These expulsions take place as part of repeated waves of mass round-ups leading to immediate deportation.

b) The titre de séjour

Algerian law governing foreigners covers not only their entry into the country, but also their stay and departure. To obtain an Algerian titre de séjour (residence permit), one has essentially two options: either come from their country of origin as a student on a student visa, or arrive in Algeria with a passport and a tourist visa. However, even in these two cases, “it can be difficult for migrants to regularise their administrative situation due to the complexity of procedures and the lack of resources to support them in this process“, according to an AP comrade in Oujda.

c) The reality of living without a legal status

Our local contacts linked to migrant communities in Algeria report:

- undocumented people find themselves in very difficult situations and are highly exposed to risks such as detention, expulsion and exploitation.

- Workers are particularly affected, forced to turn to the informal sector, where their rights are not protected and they are often left at the mercy of their employers. This vulnerability often paves the way for increased economic exploitation.

- Children’s education is also made very difficult. The children of migrants are refused enrolment in schools or on vocational training courses.

Crossings & AP cases

From March to October 2023, the Alarm Phone was involved in 19 cases on the Western Mediterranean route between Algeria and Spain. On many occasions (12 AP cases), the boats disappeared and the fate of the people is still unknown. Such is the case of a boat which left Tipaza (North of Algiers) on 07 June with 14 to 16 people on board who are still missing at the time of writing. Many more boats shipwreck, for instance a boat that left two days before that, on 05 June, with 22 people onboard. As strong as is our anger against those responsible for the border regime, our solidarity and our hearts go out to the families and loved ones of those who have disappeared or died. In three AP cases, the people managed to reach Spain and we wish them a warm welcome.

Arrests, deportations and humanitarian crisis

Time again, words fail to describe the appalling and racist practices carried out by the Algerian state against Black immigrants. In March, Alarm Phone Sahara (APS) reported a “humanitarian crisis” in the village of Assamaka, 15 km from the border between Niger and Algeria, as a result of the massive deportations and evictions carried out by the Algerian authorities (at least 24,250 people in 2022 according to APS).

The deportees are women, including pregnant women, children and men, who have often made a harrowing journey in buses and trucks across the desert. Many were systematically beaten, abused and robbed by Algerian security forces. Once in Niger, these people find themselves in total misery. Source: APS

In May, the alarm was also sounded by Guineans and Ivorians stuck in Assamaka, and a working group made up of institutional structures and civil society was set up by the authorities of Agadez. According to APS, at least 19,686 people were deported from Algeria across the Niger border “in conditions of systematic violence and abuse between 1 January and 16 July 2023.” These figures are much higher than those for the same periods in previous years. The military coup of 26 July in Niger has not prevented deportations from Algeria. 679 deportees arrived in Assamaka in convoys on 31 July and August 1, and thousands more are stranded in a deeply unstable country beset by sanctions.

5. Regularisation in Spain: difficult to achieve by design

In the Spanish state, there are different ways to regularise your situation and obtain documents. There is no easy route to have a legal status with the basic rights. Status is never automatically granted and can always be revoked. It is not a bug in the system, instead is precisely designed in this way.

The main routes are:

- Social integration (“arraigo social”): although it is in theory an exceptional way to obtain documentation, it is actually the most used. You will need 3 years of registered residence (empadronamiento), no criminal record, a job contract that meets specific requirements, and a “social integration” report.

- Family Life: Civil partnership or marriage with a person holding a Schenguen area nationality who lives in Spain, is currently working, and who does not have a previous criminal record.

- Economic integration (“arraigo laboral“): you will need to have at least 2 years of registered residence and to prove that you have been working irregularly for at least 6 months by evidencing your employer.

- Family reunification: if your direct relative holds a residence permit in the Spanish state, you may be granted entry clearance to move to Spain to join them. The family member in the Spanish state needs to have already renewed their permit at least once. Economic resources and “adequate” housing have to be demonstrated by means of a report. This process takes a long time, because you first need to prove that you meet the requirements to even make an application on this route.

- Integration via education: You may be able to receive a residence permit after doing two years on an approved vocational training course, but it does not give you the right to work. To upgrade to a permit with a right to work, you need a job offer. Those are hard to come by as employers do not want to wait for you to start work for the time it takes for the additional work permit application to be decided.

- Violence against women: if a woman get a protection order or other proof of being a victim of violence against women, she could try to use it as a ground to apply for a change of status. Proof here might be a report or a conviction against the perpetrator.

- Asylum and international protection: if the Spanish state is the country through which you have entered Europe, you have to show that there is a risk of persecution on being returned to the country of origin. In fact, this is granted in very few case. For example, in 2022 Spain only granted asylum to 16% of all applications, the European average is at an also rather disappointing 38%. However, most applicants can get a temporary card just to avoid deportation and in some cases that gives you the right to work.

- Contract at origin: if you can get a contract from a company sent to your home country, you may be able to move to Spain, but this only applies to some very specific jobs for which there are a shortage of applicants.

- Unforeseen illness: if you can prove, according to legal standards, that you developed the malady in Spain, that in your country of origin there is no access to the treatment that you need, and that your physical integrity will be at risk if you do not have access to the medical care available in the Spanish state, you might qualify for a residence permit.

- There are some other very specific, complicated and laborious routes.

Despite the existence of all these procedures, just obtaining the documents necessary for regularisation is very difficult for foreigners without financial resources. This is by design, since the system is designed to hinder access to a secure status. In past reports, we have already demonstrated how it is in the interest of European capitalism to maintain a migrant workforce without rights or legal status. People in such a position are easy to exploit. Health assistance, working rights, educational access etc. are not availabe whilst you are waiting for a residence or job permit. Even after you obtain one, it can easily be lost for a variety of different reasons. Meanwhile, the daily fear of being denounced or deported makes it more difficult to openly assert your rights, for example while doing essential works such as care or agricultural labour.

The bureaucracy is cumbersome, for instance, currently there are more than 3,000 blocked procedures just in the city of Barcelona. The procedures take a long time. Because of the slowness of the administration, the documents that people have to provide during the process lose their validity, which slows down the procedure even more. Getting an appointment at the immigration office is often impossible due to a lack of information and due to frequent collapses of the system. Sometimes, people pay high fees to “professionals” who sell appointments with the immigration authorities and thus take advantage of the dire situation. In addition, there is continued arbitrariness, mistreatment and racist institutional violence in all this machinery.

And this situation never ends. When you get your residency, you cannot rest because you always have to keep renewing you papers, meeting new requirements, paying the fees again, hiring professionals, etc. This is a way to keep people, especially those who are in situations of greater precariousness, in a continuous extortion racket. It causes pain, anguish and unending uncertainty.

In march 2020, a movement of resistance started from different migrant collectives all around the state. The movement, called Regularización Ya! calls for a massive regularisation of the administrative situation of migrant people by using the tool of a People’s Legislative Initiative (Iniciativa Legislativa Popular, ILP). This is a mechanism through which people can propose laws for consideration, debate and approval in the Congress of Deputies by collecting 500,000 signatures.

The fact that for ILP mechanism requires the signatories to hold a Spanish identity card if the proposal is going to make it as far as congress, underlines the fact that the Spanish system gives scant regard to people in the migrant community, even when it comes to their own demands and needs. Thanks to the mobilisation and coordination of lots of collectives, 710,429 signatures were collected. It at least highlighted the oppression that migrants are facing.

6. Shipwrecks & missing people

On 01 March, a dead body is found ~200 km North of Dakhla, Western Sahara.

On 08 March, the teenagers Mohamed and Yawad disappear in Alboran Sea trying to swim to Ceuta, Spain.

On 21 March, a boat with 47 people on board capsizes off the city of Argoub, Dakhla, Western Sahara. Twelve dead bodies are recovered, nine people are rescued and the other 26 people remain missing.

On 21 March, a boat with 15 people on board disappears. The boat had left Cherchell, Algeria heading to the Spanish mainland.

On 22 March, a boat with 14 people on board leaves from Oran, Algeria to Almeria, Spain. Alarm Phone concludes that nine people were rescued by SM while five remain missing.

On 22 March, a dead body is found on the Benítez beach, Ceuta, Spain.

On 03 April, Alarm Phone concludes that a boat boat with 14 people on board which had left from Oran for Almeria on 22 March was rescued. Five people remain missing.

On 03 April, Alarm Phone is informed by relatives about a boat with 15 people on board that left Cherchall heading to Cartagena, Spain. We are told that it has been missing since 21 March.There is still no news.

On 08 April, a boat with 12 people on board shipwrecks off Guelmim, in southern Morocco. Eleven of them die and only one person can be rescued.

On 18 April, two passengers on a zodiac die on their journey between Oran, Algeria and Almería, Spain. The boat had left with 20 people on board. The media report that the boat was hit by strong waves and had been adrift for one and a half days. Three people are arrested and criminalised, charged with reckless homicide.

On 19 April, 19 people, including seven women and a girl, die in a shipwreck on the Canary route.

On 02 May, Alarm Phone is alerted by relatives to a boat that had left from Oran, Algeria on 26 April with 17 people on board. They remain missing.

On 03 May, Alarm Phone is informed that the body of Azzedine and a 5-year-old girl have been found on the beach of Benslimane, Morocco. They had left Skhirat, Morocco, trying to reach Cadiz, Spain with 26 other people who all remain missing.

On 06 May, Alarm Phone reports that several bodies washed ashore in various coastal areas of Morocco, including Mohammedia, Kenitra, Benslimane.

On 16 May, a dead body is recovered in the port waters of Ceuta, Spain. The person was wearing a neoprene suit and it is assumed that he died while trying to travel clandestinely to Spain as a hidden passenger in a boat.

On 23 May, a young man is shot in the neck during immigration control when he tries to board a pneumatic boat for the Canary Islands. According to survivors, the Moroccan military fired up to four rounds of gunfire as the boat left from a beach South of Cape Boujdour, Western Sahara. Three people fall into the sea and return to Western Sahara. The survivors call for an investigation but the police arrest and deport them. On 25 May, the boat arrives in Gran Canaria, but unfortunately four more people died on the journey.

On 04 June, a dead body is found by a cargo ship in the Strait of Gibraltar, 20 km off the shore of Ceuta, Spain. He is not wearing a neoprene suit, but other aides, such as a board and a float, are found, indicating that he was probably trying to reach the coast of Cadiz, Spain.

On 05 June, Alarm Phone is informed about a missing boat with 30 people that left Nianig, Senegal. (Alarm Phone Dakar)

On 06 June, a boat with 26 people on board sinks off the Algerian coast, Al-Arhat, Tipaza. Six bodies are recovered. One person survives. The other 19 remain missing. Some of the families publish through social media the names of their children who were on board the sunken boat. These are: Salah Youssef, Masoud Muhammad, Yasmine Jawdat Saadi, Halima Muhammad Mustafa, Farman Adeeb Daly, Salah Mahmoud Youssef, Mahmoud Karaou Khalil, Masoud Mustafa Muhammad, Ola Abdul Razzaq, Lareen Muhammad, Princess Muhammad Habash, Sheyar Muhammad (Afrin), Jamila Muhammad Ali (Afrin), Ahmed Kiko, Adeeb and his wife, Farman Halim. They are all Kurdish.

On 07 June, Alarm Phone is in contact with the relatives of a boat that had departed a month before from Tipaza, Algeria with 14 – 16 people onboard, heading for Spain. The people are still missing.

On 09 June, two boats with 132 people on board make it most of the way to Almeria but the passengers are forced to swim to the coast. Two people drown in their attempt to swim to reach land.

On 17 June, Alarm Phone learns about a missing boat with 30 people from St. Louis, Senegal on board. (Alarm Phone Dakar)

On 17 June, Alarm Phone is alerted by relatives to a boat with ~50 people missing in the Atlantic Sea. The boat had left a week before from Agadir, Morocco. Families of missing people gather in front of the town hall in protest to denounce the government and demand an investigation and support from the responsible authorities. They came together to hope and mourn for their missing relatives. Two weeks later the people remain missing.

On 20 June, a fishing boat locates a rubber boat with 53 people on board, including a pregnant woman who had already died, less than a kilometre off the coast of Los Cocoteros, in Lanzarote, Spain.

On 21 June, Alarm Phone is alerted to a shipwreck with at least 59 people on the Atlantic route. Only 24 people are picked up by the Morrocan Navy. At least 35 people are still missing.

On 21 June, six people die when the Moroccan navy interfers with a boat carrying 56 people. The people had embarked in the Nador region.

On 27 June, Alarm Phone is informed that 55 people are missing on the way from Guelmin to the Canary Islands. The relatives have had no conact since they departed on 22 June.

On 01 July, Alarm Phone is informed about a shipwreck with 55 people. Only four people survive and are taken to hospital in Laayoune, Morocco.

On 03 July, a boat with 65 people on board is rescued by Salvamento Maritimo south of Tenerifa, Spain. One person is found dead.

On 03 July, Alarm Phone is informed about a missing boat that left Senegal with at least 40 people. (Alarm Phone Dakar)

On 03 July, at least 51 people die in a shipwreck on route to the Canary Islands, Spain. Only four people can be rescued.

On 11 July, the dead body of a baby is found on the beach of Tarragona, Spain.

On 13 July, a boat with 56 people capsizes off the coast of Saint Louis, Senegal. Six people are known to be dead. (Alarm Phone Dakar)

On 13 July, more than 300 people from Senegal go missing in the ocean. The people were travelling in three boats from a village in Senegal to the Canary Islands in Spain. Caminando fronteras report that there were around 200 people on one of the boats, around 65 on the second boat and 60 on the third. They are believed to have left from the village of Kafountine, in the South of Senegal.

On 14 July, a shipwreck happens in the international waters off the Algerian coast. Only one of the 11 people on board survives.

On 14 July, a boat with 40 survivors is rescued by the Moroccan navy and taken to Dakhla, Western Sahara. 20 people die during the crossing. Their bodies remain lost at sea. They had left Senegal 18 days before. (Alarm Phone Dakar)

On 15 July, Alarm Phone is contacted by relatives who are searching for six people missing in the Western Med. They had left Morocco two days before.

On 16 July, a boat is found after five days adrift far from the Spanish coast. 13 people are rescued but four people are reported missing.

On 18 July, Alarm Phone is informed about a shipwreck on 16 July off Western Sahara. The boat with 61 people had capsized. 37 people survive and 24 die.

On 20 July, at least 13 people die in a shipwreck off the Moroccan coast. The boat had left Senegal with 63 people on board. Other sources report 18 deaths.

On 22 July, a boat capsizes close to the Moroccan coast. At least six people die. 48 survive the shipwreck.

On 22 July, three boats arrive on the coast of Almeria, Spain. In the first boat a person is found dead, he probably died during the crossing.

On 24 July, at least 16 people die when a boat go downs off the coast of Ouakam, Dakar, Senegal.

On 24 July, six people drown off Nador, Morocco while trying to reach Spain when their rubber boat goes down. 48 people manage to swim back to the Moroccon shore and survive the tragedy.

On 25 July, at least 17 people are found dead after a boat capsizes off Dakar, Senegal. The boat was carrying more than 100 people and had been reported missing more than two weeks previously.

On 25 July, at least five people drown when a boat carrying about 60 people sinks off the coast of Western Sahara, according to the Moroccan Association for Human Rights (AMDH).

On 25 July, a boat with 83 people is rescued close to the island of Las Palmas, Spain. The bodies of two people are found who died during their journey to Canary Islands.

On 25 July, a boat with 84 people is found close to the island of Gran Canaria, Spain. One person dies.

On 05 August, a boat with 194 people is intercepted. The survivors and five dead bodies are brought to Dakhla, Western Sahara. Eleven people are in a critical condition and taken to hospital.

On 10 August, off the beach of Dakar, around a hundred people prepare to leave for the Canary Islands. The Senegalese police spot the group and, after firing into the air to disperse the crowd, a gendarme opens fire on the crowd as they make their way back to the houses. A young boy is hit from behind by a bullet and dies instantly. Further action is yet to be taken on this case. (Source: Alarm Phone Dakar)

On 13 August, Alarm Phone is alerted to a missing boat with ~13 people who had left from Oran, Algeria for Spain.

On 14 August, after one month of being adrift at sea, a boat is spotted in the Atlantic Ocean, about 275 kilometers from the island of Sal, Cape Verde. 38 people are rescued from the stricken boat by a Spanish fishing vessel. The Senegalese authorities have confirmed that the boat with 102 people on board departed from Fass Boye, Senegal on 10 July, en route for the Canary Islands. The IOM report that more than 60 people are believed to have died. According to the media, young people protest on the streets to express their grief and anger. They accuse the responsible authorities of delaying search and rescue operations.

On 22 August, Alarm Phone is informed about a boat with ~60 people who left from Akfhenir for Lanzarote, Spain. On 28 August, Alarm Phone learns that the boat was rescued by Moroccan authorities. Six people died trying to cross.

On 24 August, relatives inform Alarm Phone about a missing boat with ~20 people who left from Casablanca, Morocco for Spain. On 30 August, Alarm Phone finds out from relatives that there had been a total of 25 travellers on the boat. Ten people returned to land after having spent eight days at sea without food and water. 15 people remain missing.

On 28 August, Alarm Phone is informed that 12 boys who left from Algiers, Algeria towards Spain have disappeared.

On 30 August, a boat with 58 people on board capzises off Tan-Tan, Morocco. Three young people disappear at sea while attempting to reach the Canaries from the Moroccan coast. Six people are rescued by a fisherman.

On 31 August, Alarm Phone is informed by relatives about a missing boat with 46 people who had left from Tan-Tan, Morocco five days before in an attempt to reach the Canary Islands.

On 31 August, another boat goes missing along the Algerian route. ~11 people left Mostaganem, Algeria on 25 August, heading for Spain. After more than six days at sea, the people are rescued to Cabrera island, Spain. One of them dies during the crossing.

On 06 September, a person disappears swimming from Morocco to Ceuta, Spain.

On 10 September, a shipwreck happens 80km from Gran Tarajal, Fuerteventura, Spain. 12 or 13 people drown before rescue arrives, 38 people survive.

On 14 September, Alarm Phone is alerted to a missing boat with 10 people in distress between Oran, Algeria and Spain. The travellers left on 11 September, and since then nobody has heard news.

On 14 September, another boat with 16 people who left from Mostaganem, Algeria is reported missing to Alarm Phone.

On 16 Septenber, a boat from Tan-Tan, Morocco catches fire. ~10 people were hospitalised in Morocco. They report that some people burned alive. Others jumped in the water and haven’t been seen ever since. Amongst the survivors, those severely burned are still hospitalised. The others have been arrested and fear repression from the Moroccan authorities on top of having endured this traumatising experience

On 17 September, Alarm Phone reports a shipwreck on the Algerian route. More than 25 people who left Mostaganem on 11 September die trying to reach Spain.

On 19 September, a dead body is washed ashore at Playa de la Ribera, Ceuta, Spain. It is presumed that the person has died trying to swim from Morocco to Ceuta.

On 20 September, a person dies during the attempt to swim from Morocco to Ceuta. His remains are washed ashore at Playa de la Almadraba, Ceuta, Spain.

On 22 September, ~38 people go missing in the Atlantic sea.

On 28 September, a boat with more than 30 people reaches Cadiz, Spain. At least one person dies during the six day journey.

Disclaimer on our terminologyAlarm Phone is a network of volunteer activists. The bulk of Alarm Phone members in the Western Med and Atlantic region are West African or European in origin. As a consequence, we are much more embedded within the communities of people on the move from West African countries than we are from the Harraga communities of the Maghreb. This inevitably leads to the underrepresentation of the experiences of the latter group. The only way to rectify this problem is to expand what we do and work to build a truly transnational community of resistance. This is slow and laborious work, but we are committed to doing it. The language that we use is important. The words that we use also carry the weight of their history, and that is a history of power. We constantly struggle to view the world correctly and to find the right descripition of what we see. There is no single viewpoint that will encompass everything. To see the world correctly, we need a kaleidoscopic view. This report is a collective endeavour. Many of the authors are not writing in their first language, and most of the witness testimony is also given in a second or third language. We consider this a strength. We do not wish to regiment the language used in our descriptions of people and their backgrounds. Where someone might baulk at ‘sub-Saharan’ as implying inferiority and prefer ‘Black’ or ‘Black African’, another might reject the racialisation implicit in the latter terms. Equally, some of us avoid talking of ‘migrants’ and prefer to emphasize personhood with ‘people on the move’, but for others of us this language is fussy and unnatural and we are proud to be migrants. We have left, as much as possible, the authors’ different choices of description, especially where the author is herself a person on the move. |