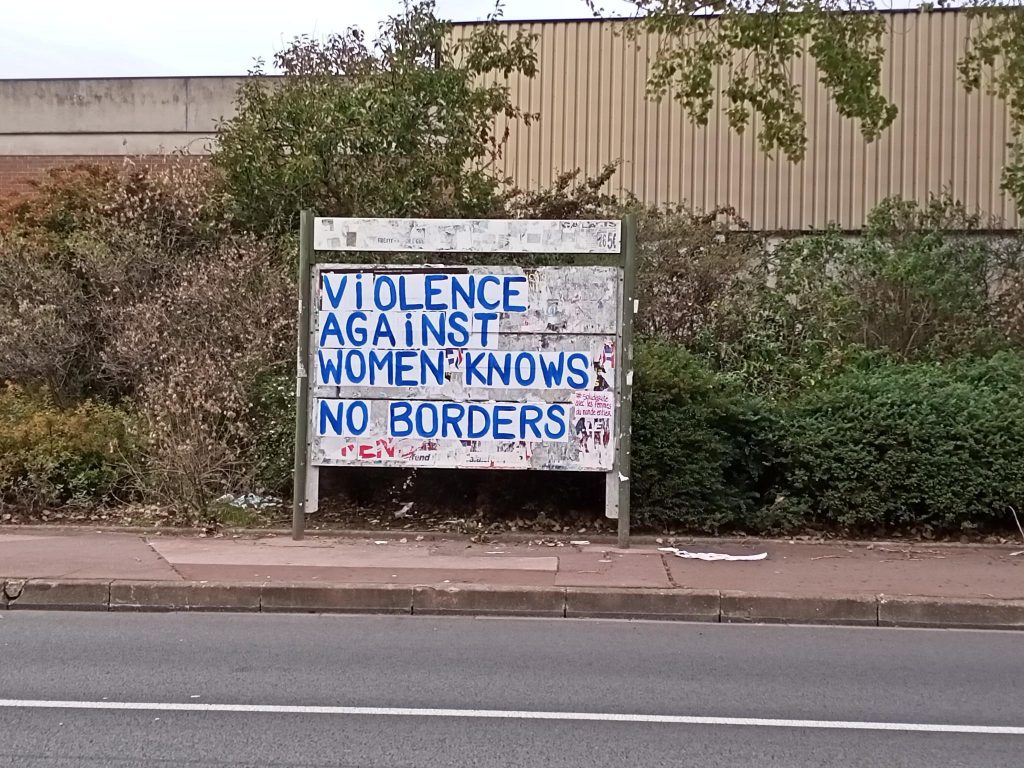

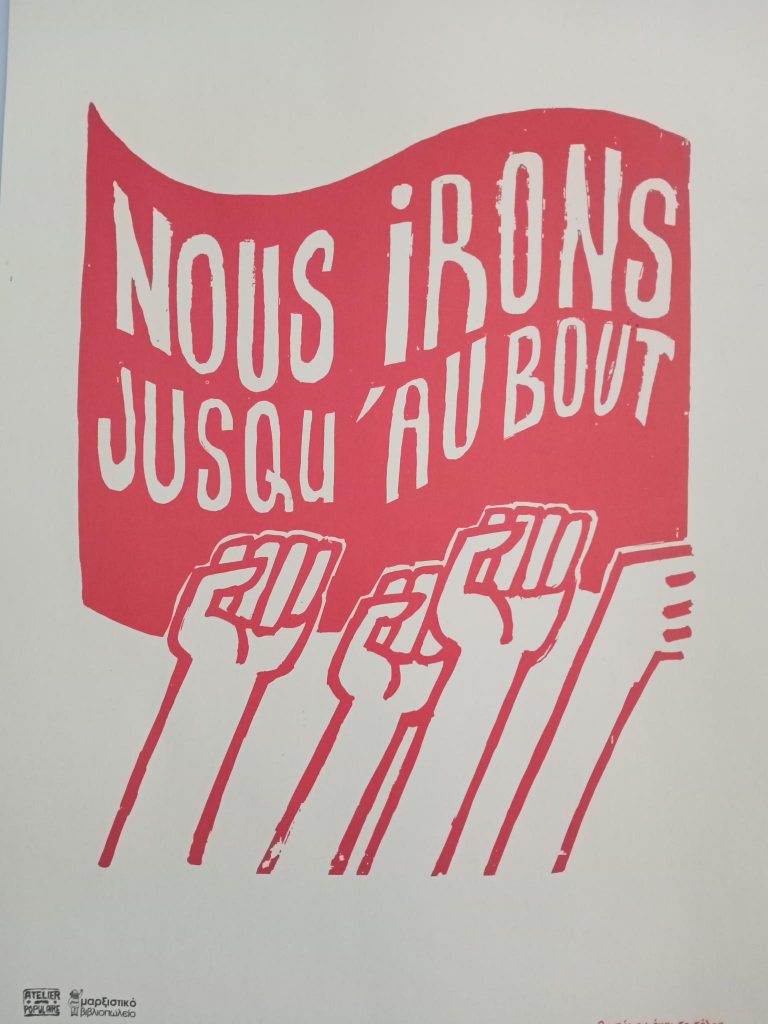

“We will go all the way”, Athens Greece, 2021. Photo: Alarm Phone

“We will go all the way”, Athens Greece, 2021. Photo: Alarm Phone

All through 2020, the health crisis has made daily life and access to rights even more difficult for people blocked and mistreated at Europe’s borders. This report was supposed to be published on the 8th of March 2021, but it was not possible to do so. We don’t want to keep these stories, texts and information in a box, as they are part of the relationships we build and the experiences we share in our struggle against borders with women and LGBTQI+ people. We have therefore decided to publish it at the start of the new year 2022 during which we will continue to fight in solidarity with people on the road. Alarm Pĥone’s previous reports on/with the voices of women and LGBTQI+ people published in 2018 and 2020 can be found here.

We have structured this report on the basis of texts and actions carried out by feminist border groups and on the basis of interviews and testimonies. The following are some of the questions on which this report is based:

More concerning women’s experiences:

Do you feel you have found solidarity on the route with other women who were on the move?

What is in your opinion the difference between taking the journey as a woman and as a man?

Can you tell a bit about the journey across the sea? Which role did women play during the journey?

Referring more to queer interviewees:

How have you experienced the journey?

Have you found a supportive community along the way?

Both:

What made you decide to leave your home and start the journey towards Europe?

Has the journey been as you expected, or very different from what you expected?

What are your dreams for the future?

What would you like to change for people who have to travel towards Europe in the future, and how do you think we can work towards that change?

Table of Contents

Morocco

A look back at the 8th of March in Tangier

Greece, Lesvos

Queer resistance and solidarity in a hostile environment

Border feminisms -WISH-

From Turkey to Greece: interview with P.

Solidarity experienced at the borders

MOROCCO

Tanger, Morocco, 2021. Photo: Anonymous

Tanger, Morocco, 2021. Photo: Anonymous

The situation in Morocco continues to be extremely concerning for those people, particularly women, who would like to cross the Mediterranean Sea and reach European territories. The Atlantic Route towards the Canary Islands has become increasingly deadly in the past year and a half and this is also one of the consequences of the criminalisation of migrants who are often arrested in the north of the country, Tangier for example, and sent to the south, where most of the journeys towards the Spanish Atlantic Islands start. Beyond the deaths at sea and missing people, who we remember and mourn, other situations of danger, particularly for women and children, arise in the forests around Nador, closer to the Algerian borders. The Alarm Phone Western Mediterranean and Atlantic Regional Analysis (1 July – 31 October 2021) reports that “women frequently report to our local AP team having suffered from sexual violence and exploitation. Some women also tell of being arrested and pushed back by the Moroccan police on multiple occasions. The common experience is to be held for whole days in prison cells and then to be released at night or pushed back to the ditch at the Algerian-Moroccan border.” Despite all the violence, risks and uncertainty, it’s with enthusiasm that we witness and share the 8 March Women Manifesto in Tangier, as a testimony of women’s movements and activisms at borders that fight for the freedom of movement.

8 M TANGIER

On the 8th of March 2021, women gathered in Tangier to celebrate and reflect on their struggle as women on the move, fighting a deadly racist border regime. As covid restrictions didn’t allow for them to take to the streets, they hosted a discussion on Alarm Phone work, made interviews with each other and ended the day with a meal together.

For us, the women, the activists, we are on the ground with all the risks we face day to day. And this is what gives us strength to continue our struggle as women and fight for the people’s right to freedom and well-being. So, we launch a solemn appeal to our leaders to do good. Respect the International Conventions and give more consideration to the fighting women, who fight for the good of the world on this day. Also, our sincere thanks to the big Alarm Phone network for the financial support, which was well received by our sisters who suffer at the borders waiting to travel. It has allowed us to have a clearer picture of how many people die every day at the borders, and made us see that this struggle must not stop. Hand on the heart.

Tanger, Morocco. Photo: Anonymous

Tanger, Morocco. Photo: Anonymous

_________________________________________

GREECE, LESVOS

During the past two years, we witnessed an escalation of violence against people on the move who are trying to cross from Turkey to Greece. Since March 2020, the Greek Coast Guard, supported by the EU border agency Frontex, carried out more and more illegal pushbacks. Boats that have already made it into Greek territorial waters are violently pushed back into Turkish waters and left adrift there. The Hellenic Coast Guard circles around refugee boats creating dangerous waves or they take away fuel and motors to stop boats. Often, boats are being towed towards the Turkish coast at high speed or migrants are forced into unseaworthy life rafts and then left adrift at sea to fend for themselves. Almost every group that tries to cross the Aegean Sea by boat is subject to severe violence and pushbacks by the Hellenic Coast Guard. Therefore, migrants often have to try several times before their make it to Europe. We often witnessed how groups that already made it to Greece and voiced their wish to apply for asylum were violently pushed back.

Even when one makes it to Greece, the ordeal is far from over. With long asylum procedures, migrants are stuck in detention centres and camps for months and years often in inhumane and trying conditions. Especially for women* and LGBTQI+ people the situation in the camps is particularly bad and dangerous, as the reports in this reader will show.

With more and more violence and deterrence, less and less people actually make it across. While in 2019 around 75.000 refugees arrived in Greece, numbers dropped to 15.000 in 2020 and around 9.000 in 2021 (according to UNHCR). Pushbacks and deterrence also make the crossing a lot more dangerous. Last year again, we witnessed many shipwrecks in the Aegean. Around Christmas 2021 there were four different boats on their way to Italy from Turkey that wrecked in the Greek Search and Rescue Zone. More than 30 dead bodies were found, but a lot more people went missing. Our thoughts are with the survivors and with the relatives and friends who mourn their beloved. We will never forget them. Only open and safe routes towards Europe will prevent such tragedies in future, which is why the Alarm Phone continues to struggle for safe passages and the right to Freedom of Movement.

_________________________________________

Queer resistance and solidarity in a hostile environment

The readers of this publication will be well aware that Lesvos is a place of violence, deprivation, suffering and despair. Recent developments, such as the fire that destroyed Moria Camp, the harsh coronavirus restrictions that are used to specifically target refugees and segregate them further from the rest of the population of the island, as well as the ongoing fascist presence on the island, have led to a continuous deterioration of the living conditions for refugees on Lesvos.

This article was written collectively by LGBTIQ+ Refugees on Lesvos. And in the experience of our collective for LGBTIQ+ refugees, people who are part of a sexual or gender minority face an even harsher set of challenges.

A hell within a hell

LGBTIQ+ refugees suffer from racism and xenophobia like any other group, but are also simultaneous targets of homophobic and transphobic violence. LGBTIQ+ refugees lie at the intersection of several forms of discrimination. Groups that lie at the intersection of several forms of discrimination face much more severe discrimination and hatred. LGBTIQ+ refugees are one of the most vulnerable groups facing this harsh reality.

Most of us have experienced violence. We are beaten, sexually assaulted, threatened with knives and propositioned for sex. This harassment is not a matter of isolated cases, but a daily reality. Unfortunately, we face many incidents of severe sexual and gender-based violence. Sexual exploitation and other forms of sexual violence are extremely common for trans* persons. Gay men are also regularly sexually exploited, with people threatening to ‘out’ them to family or other people in the camp if they don’t comply.

The violence is particularly severe in the camps where we are forced to live in close proximity to the very communities we are fleeing from, because accommodation is organised by nationality. However, harassment and violent attacks take place in many other locations across the island, namely public space, public transportation and NGO-run spaces.

The Greek government does not offer any specific protection measures for LGBTIQ+ refugees. The Greek police not only refuse to provide protection, but often make homophobic and/or transphobic comments themselves, and even threaten us with violence when we seek redress.

Safe spaces or shelters are at capacity, and many of them are threatened with closure by the Greek government. Even if an LGBTIQ+ refugee manages to find safe shelter outside of the camps, due to the geographical restriction placed on refugees’ movement, we are in any case forced to continue to live in close proximity with the perpetrators of violence against us. We continue to fear retribution from them.

A prejudicial asylum system

The Greek government also fails to provide access to a fair asylum procedure on Lesvos. Besides the manifold and well-documented dysfunctionalities and injustices of the asylum procedure, LGBTIQ+ individuals face additional hurdles. LGBTIQ+ refugees are often unaware at the time of their arrival that their sexual orientation or gender identity can be a basis for claiming asylum. This contributes to late and poorly prepared legal claims.

Additionally, many of us are scared of disclosing our stories to officials, as there is no privacy during most asylum procedures, especially during the initial registration. There are many accounts of individuals who do not identify themselves as LGBTIQ+ in front of authorities at the earliest possible opportunity, who are then punished for their hesitation, with their genuine asylum claims being written off as lacking credibility. We may never have ‘come out’ publicly, or even spoken aloud about our sexual orientation or gender identity before, and yet we are expected to come out in a setting in which we feel unsafe and unprotected. Late disclosure continues to be used to discredit our claims. Increasingly, interview dates are announced at short notice. This makes it especially difficult for LGBTIQ+ refugees to prepare, since they find it difficult to speak publicly about their identities and may well have experienced significant trauma.

The use of stereotypical, homophobic and transphobic notions to identify LGBTIQ+ individuals also routinely results in the rejection of our cases. Asylum service officers often fail to understand our claims, because of assumptions and prejudices. These include, among others, the expectation that we: have a partner or are sexually active; take part in LGBTIQ+ activism; or are able to provide a ‘coming out’ narrative.

Despite UNHCR, EU and also domestic Greek guidelines mandating otherwise, outlandish, invasive methods are routinely used by the asylum services to investigate the validity of our claims. There are examples of individuals having their asylum claims rejected on the grounds of their behaviour not appearing “gay enough”, not “trans enough” and, paradoxically, for appearing “too girlish” to be “authentic.”

This is due to a lack of adequately-trained officials, who instead rely on homophobic, western-centric understandings of LGBTIQ+ identities, invasive interrogations, or sexually explicit evidence. Several members of our group have been asked sexually explicit questions during the asylum interview. One was asked to re-enact his rape. In addition, some case workers proved to be extremely uncomfortable during the interview, exhibiting homo- or transphobia and a clear lack of training on this sensitive subject.

In this context, translation is another main concern. Translation is essential during the asylum interview but also to access many basic services on the island. For us, translation comes with danger. Many translators have a hostile attitude and refuse to translate for us. When they translate, they often translate imprecisely or incorrectly. “Gay” might become “paedophile”, “gay” and “trans” get mixed up, and some translators simply lack the vocabulary to describe us. In a context where coherence and credibility are of extreme importance, this can have enormous consequences.

The translators are recruited directly from the refugee community and often live in close proximity to us, leading to negative experiences after the interview. We often fear that translators will either directly use violence against us, or tell other members of our ethnic community about our identity. Some of us come from such small linguistic communities that we might even share a tent with the only available translator.

A community of solidarity and love

This is only a small glimpse into our everyday reality on this island which we call hell. There are many other specific struggles we face in the fields of healthcare, detention and accommodation. While other refugees on the island often rely on family or ethnic networks to cope with this harsh reality, we often cannot. This is why we decided to get organized among ourselves, and create a community of solidarity and love.

The “Lesvos LGBTIQ+ Refugee Solidarity” collective has been active since July 2017, building community by providing a safe space for LGBTIQ+ refugees in Lesvos where everyone is free to express their sexuality and/or gender identity in an environment of mutual support and respect, without fear of judgment or harm. We meet in a safe and confidential location that is only shared among people that we trust, and have a non-hierarchical admissions process to ensure safety as our utmost priority. We have strict confidentiality policies to mitigate the dangers of being identified as LGBTIQ+ on Lesvos. All decisions are made transparently, and responsibility is spread as equally as possible.

We unite in a non-hierarchical group structure that includes LGBTIQ+ refugees, locals, and international volunteers. We prioritise the safety of our group members, with most group activity performed discreetly to protect individual members’ safety. Group decisions are made collectively during group meetings and assemblies. We aim to provide support where there are no other alternatives, and to remedy numerous problems within the asylum procedure created by systemic issues within both governmental and non-governmental structures. Collectively, we demand changes to the situation for LGBTIQ+ refugees trapped on Lesvos.

We came into existence organically, and in the absence of any actor on the island providing specific information or support to the LGBTIQ+ refugee community. Members of the LGBTIQ+ refugee community began to identify members of the non-refugee LGBTIQ+ community as trusted points of contact and support. We are a collective of LGBTIQ+ refugees, volunteers, activists, single mothers, people who were formerly incarcerated, survivors of violence, locals, and allies who work together to build solidarity and mutual support on the island of Lesvos.

Although the group has no official status as an organization other than a solidarity and support group, we meet every week to provide a safe space to talk, organize and share useful information specific to LGBTIQ+ refugees. If no alternative can be found via another organization or humanitarian actor on the island (due to lack of provision, administrative issues or long delay where the situation is urgent), the group has in the past provided support in the form of safe housing, coverage of legal fees, medical support (including private care where the individual in question has no access to the public system or transfer to the mainland), food, sim cards, and bus passes, among other things. In recent months, the demand for support among our group members has greatly increased due to COVID-19, the increased presence of fascist and ultra-right individuals and groups on the island, and the resulting political and social turmoil.

Based on deep mutual trust that this community was able to establish between its members over the years, the collective has become a safe place where people have the freedom to express their most profound identity, and sense of self in an authentic way without fear of persecution. This dynamic has led to the accumulation of knowledge on the specific struggle against violence and discrimination towards LGBTIQ+ refugees. However, the current use of COVID restrictions to limit the mobility of refugees, as well as general restrictions on refugee mobility, have made it more and more difficult to be with each other. Many of us must remain stuck for weeks on end in a hostile environment.

Lesvos is not a safe place for LGBTIQ+ refugees. This is why we are asking allies around the world to support us in any way they can. This can be in terms of advocacy or financial support, but also by joining us as allies here on the island, and using their privileges to help us manoeuvre through this hostile environment.

More information and the best way to contact us can be found on our Facebook at: https://www.facebook.com/LesvosLGBTIQRefugeeSolidarity or via email: lesvos.lgbt.r.solidarity@gmail.com

Lesvos, Greece, 2022. Photo: WISH

Lesvos, Greece, 2022. Photo: WISH

_________________________________________

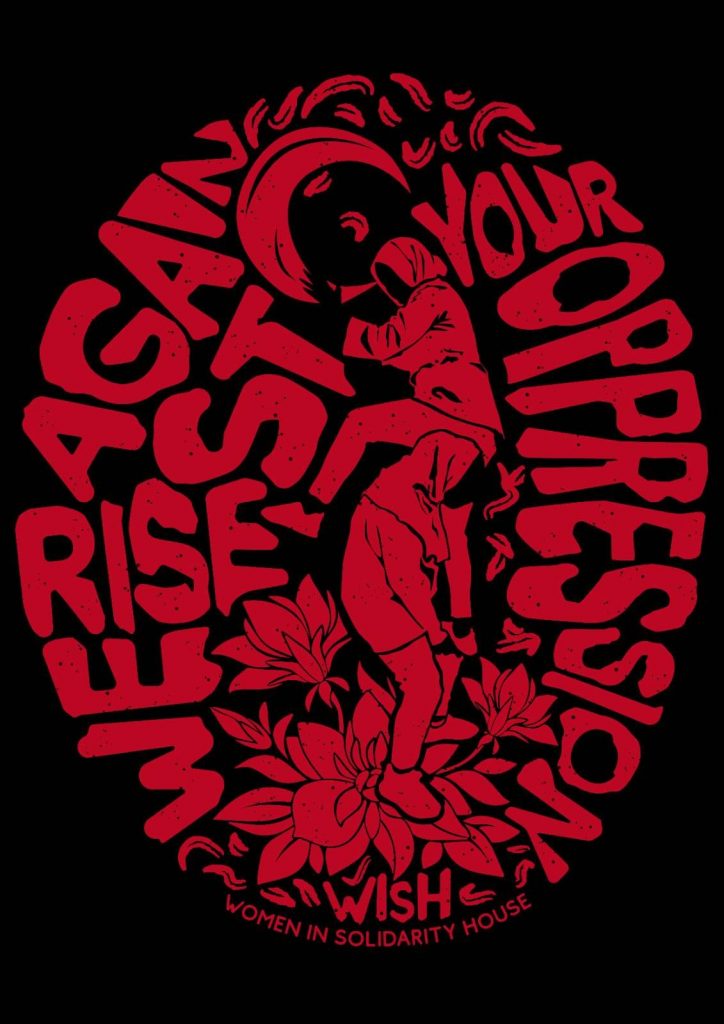

Border Feminism

On the other side of the Mediterranean, the WISH group based on the island of Lesvos in Greece published this text and created the concept of “Border Feminism”. Alarmphone published this manifesto for 8 March, but we would still like to keep it in this report.

In one year everything can change. 2020 has reshaped reality on the island of Lesbos. On the borders there is hardly ever time to rest, to celebrate small victories. One must always remain alert and ready to resist the onslaught of power, which seems determined to destroy every last redoubt of hope, self-organisation and solidarity. The narrative that defines 2020 as a lousy year because of the consequences of COVID-19, has made invisible a disastrous year at Europe’s borders where there has been a drastic setback for the rights of people on the move.

We started 2020 with hope, happy to meet each other in the streets, to know that we had managed to stand up despite the weight of threats, fear and hopelessness. The first women’s demonstration on the island. Our voices were heard after a long silence. But we were never really silent. If you paid attention, you could hear our voices among the tents of this camp of shame, among the noises of fights and knives of men broken by violence and borders. We were still searching for a way to free ourselves in a space as hostile as the borders of Fortress Europe. Those in power wondered how it was possible that despite all the efforts to destroy us as individuals and as a collective, we were still able to rise up!

But at the borders, there is hardly ever time to celebrate small successes. Shortly afterwards, we saw how the racist and patriarchal system reacts with all its fury when those who should respond to the mandate of silence dare to raise their voices. The violence that was unleashed was intended to return us to the place of submission that we are accorded. If the demonstrations at the beginning of 2020 shouted “we are no longer afraid”, this year we have experienced a series of events that have reinstated fear and hopelessness.

Demonstrations were met with tear gas, beatings and identifications. Corrective measures against women and children who were peacefully demanding a dignified life. They wanted to remind us that there are no rights for us, neither social nor political, at the borders. Together with the police, extreme right-wing groups were reactivated and took control of the streets. Groups of civilians organised themselves at different points on the way to the camp, and armed with steel sticks they demanded documents from people.

Shortly afterwards we discovered the Greek government’s plans to build a closed camp, a prison. Paradoxically, the hatred of the extreme right-wing groups, which is so immense, pushed them to stop the construction and expel the police who were trying to protect the construction. This victory reaffirmed their sense of omnipotence, and they took advantage of it to attack people and cars of those they identified as members of NGOs. A system of terror was installed on the island, and migrants and all those in solidarity were attacked in the streets, with impunity. Total hostility was normalised. NGOs pulled out their volunteers for security reasons, as if it were a war. Because this is a war. They left with their passports. We were left waiting for the next blow.

It was still March. Turkey announced that it was opening its borders with Greece, and the European Union took the opportunity to close its borders definitively, in violation of international asylum law. It set up a system of violent pushbacks that abandoned all those who tried to reach Europe on a raft without an engine, floating in Turkish waters. The only right guaranteed to migrants on this island, the right to seek asylum, was thus effectively annihilated.

The COVID pandemic has only facilitated what the police and the Greek state failed to achieve, the establishment of a closed prison-like camp. A confinement that never ceased, the agony of waiting for the Corona to enter an overcrowded camp, the frozen asylum processes, the anguish of living every minute in what was increasingly a detention centre, hell.

When you have been denied any form of political expression, the only thing left is violence and fire. Fire as the last resort for liberation. Faced with the first cases of corona in Moria, tension and fear escalated rapidly. Calls were made to move the infected people out of the camp, and in the absence of a response, the reaction was fire. But it seems that borders are fireproof. They built a new camp, closed again, by the sea to see if they can drown us this time, where there is still no safe area for single women, no electricity, where there were no showers for more than a month. A new stable to continue with the torture to which we are submitted in the face of the complicit silence of governments and the population.

These are the kinds of violences that are inflicted on women at the borders.

Women and girls are trapped in the game of geopolitics of the European Union, one of the centres of dominion of racist and patriarchal capitalism.

This year we have lost a battle and have been silenced again. We are still exposed to the fire, which continues to be the only element that makes us visible. The fire with which we ignite so that they will let us be, the last stronghold of our possibility to choose our own bodies. The comrades tell how one of the last fires in the new Moria camp was set by a woman, eight months pregnant, who set herself on fire when she was refused a transfer to Germany because of her advanced pregnancy. She took her children out of the tent and set herself on fire. Despair and fire. Our bodies burn from injustice and neglect. But borders are fireproof. The exercise of keeping ourselves alive puts our own lives at risk. The system wants us dead.

To the surprise of those who think this is the end, we announce that the struggle continues. Despite the innumerable forms of violence, we continue to look for ways to continue resisting and building a future with justice. This is our feminist struggle, the struggle for life. If feminisms speak of women, border feminisms speak of detention camps, of pushbacks, of unjust and degrading asylum systems. Borders cross our bodies, they murder and mutilate us. Today we want to appeal to the women of Europe. Their silence oppresses us. Our rights are not recognised. We need to build bridges that allow us to be stronger, to reach further, to destroy the borders. These borders that also divide women, that prevent us from recognising each other. The system will not fall if the borders do not fall.

Smash the patriarchy, smash the borders!

Women In Solidarity House (WISH) Lesvos

Email: wishlesbos@gmail.com

Facebook: #wishlesb

https://www.instagram.com/womeninsolidarity/

Logo of WISH, Lesvos, Greece, 2022. Photo: WISH

Logo of WISH, Lesvos, Greece, 2022. Photo: WISH

_________________________________________

From Turkey to Greece

In Lesvos we met P., 18 years old, who experienced migration routes, the sea crossing and the life in camps. She traveled with her family.

Recorded words from P.A.:

We lived in Turkey for one and half years… we were around six months in Istanbul and one year in Zakaria. The conditions for the women who are traveling with their families are better, because most of the duties are done by their parents, husbands and brothers… but those that are alone they should get more attention… UNHCR is supposed to give them the necessities and a safe accommo-dation but they are not doing so… mostly the single mothers sleep in houses with any other people… so nobody can guarantee the safety of these women in that apartment. A lot of the single mothers or the single girls are trying to have someone with them or are trying to find a Turkish man in order to not be exposed to… you know… because the girls must raise some incomes. If she is faced with violation and if she is courageous enough, she can go to the police station… but most of them are not able to complain and they stay silent… oh yes, I mean, most of them they don’t complain. A lot of the women are working illegally in tailoring workshops… from the morning until the late afternoon… they are paid less than the Turkish people… the factories owners are really using this opportunity … and it’s not a guaranty that these places are safe… anything can happen… so many of these women get psychological problems… but there is no other solution… all other doors are closed. And there is even for the very young ones no chance to go to a school in order to learn the language… everything is so expensive.

I was looking for a job, but I couldn’t find one… even I was not able to visit the school… for that they are asking for an asylum number and we didn’t have one… we didn’t want to get the ID of Turkey, because my father was faced with some political problems and he was not feeling safe… so, we lived secretly in an apartment and were trying to stay at home as much as possible. It was very hard. After working some months in the factories most of the people start finding a smuggler. I think the understanding and definition of the smugglers in Europe, where they are condemned, is different from that what we experienced. i don’t want to defend this business… but the smuggler means somebody who is the captain of the boat, who is guiding us to find our way and to pass the border… many of them get in there by chance and are not aware of the dangers they put the people in… they really try to help and keep us safe… of course… the unscrupulous criminals exist… but we had nothing to do with them on our way. There is a famous place in the middle of Istanbul… where many people find each other, checking the prices, discussing about everything and starting their journey together… this is something… I mean… the smugglers don’t give requests to the people… people are finding them… the ones paying more have at least a little guarantee… the ones paying less have almost no guarantee to pass the border. When we started to get into the rubber boat, especially for the women, it was very hard… it was a big question whether to give your hand to the smuggler to get help or not… many of them were trying to keep the distance to avoid physical contact, because it is banned according to our culture… but they had to accept that the smuggler gets closer… so they were not feeling relaxed…

It’s easier for the married women who had their husbands or brothers with them… but for the single mother, or unaccompanied and single girls it’s quite risky… it depends also on the personality of the smuggler. But danger may come also from the single boys who are in the same group. For the smugglers the women are usually vulnerable persons… they are not talking to us… they do not abuse us… but anyway… disrespectful treatment happened so much during the journey… too much… but if they are violent they mostly attack the men. We tried to cross the border five times and got arrested each time. Sometimes we ended up in the forest… sometimes we got arrested on the shore or in the middle of the sea. After that the Turkish police brought us in a detention center… that’s hard, you know, they checked us… there are police women… they asked us to take off all our clothes… they are doing that… all our clothes and even the underwear… everything… because they wanted to see if we were transferring drugs or not… it was very very bothering… that they were asking us to do that. The conditions of those camps are awful… insufficient food… the clothes are always wet… sometimes they don’t give back the bags. They kept us for approximately three nights there… after that they transferred us back to the places we came from… in our case to Istanbul… but the families who are not able to pay the money for the bus in order to return, they had to stay a longer time… After our third effort to pass the border, they asked us to sign a paper… it was written that we have only fifteen days to leave Turkey… if we will not do so, they are going to deport us to Afghanistan… and we had to sign. In our attempts to cross the sea it was always the most experienced man of our group who was operating the engine… mostly a single man… and we decided all together who had to do that.

Before our Departure the smuggler informed us about the danger for the person guiding the boat to be arrested and convicted by the Greek police… we were aware of that… and of course… we did everything to protect this person. When we finally arrived in Greece, we insisted that our driver was the son and the brother of one of the families on the boat… and so far nothing happened to him. And of course… the men are really happy if one of the women is able to call the coastguard and to deal with the officer on duty… they think if a woman says that she is a mother or a single girl and if she shows clearly how distressed she is that may fasten the rescue process… and the authorities are more likely to consider to help. We had heard that the person who calls the coast guard also runs the risk of being arrested… that’s also a reason that the men prefer if women call the authorities… because they think that the police would never assume that a woman could be a smuggler. When we finally passed the sea border and got close to the Greek shore, we didn’t know where to stop the boat. Even though we were afraid, because we knew about the dangers threatened by the police, me and another woman decided to call.

_________________________________________

Solidarity is our strength that no one could steal from us

In the daily life of women on the move, solidarity, at one time or another, is an element that shapes the path, sometimes draws the way, solidifies the bodies, energizes the hearts and strengthens the spirit. Fortunately, we have this solidarity because it is also difficult, if not impossible, to fight for our rights or to assert our rights when we are only passing by. The authorities know this and abuse it.

Solidarity is there because we women also know what it is to help. In this society shaped by men, we are educated with this mission to take care. Today on the road, we use this mission given to women by men, to survive and fight violence against women along our way.

From the solidarity we have encountered so far, mutual help in daily survival, strategies, protection between sisters, life-saving encounters have emerged.

Being a migrant woman entails the risk of a double oppression within our patriarchal and capitalist society. Being a migrant woman also means belonging to a community that supports each other and is therefore a strength. As S says, “between women we understand each other, we feel each other, we know what it is to be a feminine being (….)”

Self-organisation is everywhere on the road, self-organisation between refugees, between communities of religion or geographical origin, and also between women within their communities or in inter-communities. “For us, solidarity is the very substance of this self-organisation: This is what gave me shelter, food, clothes, medicine or food for my child: this is what gave me the morale and the strength to continue.”

Together we train each other, we teach each other how to do things, this gives us power and strength

“This solidarity that we experience every day is our strength and makes each of us stronger. Through this solidarity we grow from those who know nothing to experts. On the boat, for example, during the crossing, when you have already experienced a pushback like I have, you are the one who reassures the women for whom it is the first time: they were afraid and shouted that the water was going into the boat. I told them that no, that the water was coming from the waves, that it was normal, that the boat was not sinking.”

S: “In Moria I met two women from my country. Together we found this organisation that helps women and we also found accommodation. The first time we had a meeting in the cafeteria in front of Moria to meet a contact who wanted to help us we took a knife with us to the meeting because we were afraid and you never know. We did everything together. We would go and meet the organisations that were helping together. Being with them allowed me to do things without being afraid.”

Among women we set up strategies to survive and to stay safe

N: “I went to a place inside the protection area for single women, I got the help of women that I met there. They were hiding me in the container and did everything to keep a bed for me because a woman left and a bed was free. Also, one of them gave me her urine and when I went to MSF I could have a paper from the doctor mentioning that I was pregnant and with this paper i could have a place inside the section for pregnant women.”

By supporting each other we save lives

S: “I left my country because I left the religion and because women have no rights, neither in my country nor in this religion. When I received the second rejection of my asylum application, my lawyer called me and told me that I had to leave Moria. I started to hide. The next day it was like a miracle because an organisation run by a woman from my country to help women here who have fled our country, called me to say that they had accommodation for me in town. It was like a miracle. I was so afraid of being arrested and deported. In my country I belong to my father and I ran away. I can’t be deported there. My father will definitely kill me.”

Sh: “When we were dropped off by the coast guard on the beach, a woman doctor came to see me. I said about my diabetes: she was shocked that my levels were so high. She gave me some medicine and asked for some special food for me and with a nurse, they kept an eye on me all night and they forced me to drink water, to drink a lot of water.”

A: “When I arrived at the camp, I was crying a lot and all the time: a lady refugee who I won’t forget helped me. I arrived with no money and a two-month-old baby. I knew nothing, I had nothing. She encouraged me, I was always afraid: she told me to hold on: she gave me clothes, she gave me food… My life was meaningless. I had no news from my husband and I had been abused by men in Turkey who made money by locking me up and sending men to abuse me even though I was heavily pregnant. I stood my ground thanks to this woman really.”

Solidarity between women to feel protected, to keep my dignity, and my morale

A: “A compatriot in the camp put me in touch with an organisation that helps women. I got up the courage to call her. It was a God send. I understood then that life would go on: every meeting with S made me happy. I could look forward to the future. Even if I went back to the camp, I came back to the container with a smile.”

N: “In prison in Turkey, I had nothing to eat. The other women shared what they had bought and when they went to the prison market, they always brought me something.”

S: “I was alone when I arrived at the camp. I survived because of the women I met there. In the section I met a woman I called Mama. She was a big African mama. She protected me. She liked me. I used to go and see her and her friends when they got together. I was curious about their culture.”

To stand close to each other to fight racism and to lodge a complaint against the men who attack you

N: In prison in Turkey, we were guarded by men. When we had our period, we had to ask the guard for sanitary napkins. They gave them to us one by one: So, every time we had to ask them to change: Depending on the guards, they gave sanitary pads or not and sometimes some of them said they didn’t give them to black women.

G: One day I was raped by several men in Moria. At that time I was sleeping in a tent in the camp. I was already in contact with a women’s organisation that helps women victims of sexual violence. A lawyer and an interpreter from this organisation came with me to the police station in Mytilini to file a complaint. They stayed with me and really helped me when I filed the complaint. When we came back from the police, I got a place in the protected section for single women and a week later I got an accommodation outside the camp. It was thanks to a Cameroonian woman I met in the camp that I got in touch with this organisation. We were cooking water together, I was stressed, very stressed. Her she was visiting the camp. She asked me why I didn’t have accommodation in town. She gave me the number but told me not to say that it was her who gave it.

On the road, women are thrown into a solitary life or one that does not go beyond the family framework, “so we are wary, we are often afraid, and it is hard to create bonds of trust when there is no time for that because the road takes its course. This is where international solidarity is important, in order to create drop-off points that recharge our batteries: places where we can get together as women, meet each other, support each other and think about the next steps together”.