Conni Grenz in cooperation with Sarah Slan and Johanna Lier

Most sea crossings by refugees trying to reach Europe take place on the route between Libya and Italy. Refugees are forced to board overcrowded boats that are not suitable for use at sea, making this route the deadliest. Without the NGO search and rescue boats (SAR-NGOs), the number of deaths would be far higher, because the capacities of the official coast guards are insufficient. Until recently, the Italian coast guard deliberately stayed away from the Libyan coast and EU forces of Frontex and the military operation EUNAVFOR Med focus their efforts exclusively on reducing the number of crossings by fighting smugglers.[1] There is no unified Libyan coast guard, only multiple, autonomous formations, of which some even operate as smugglers.

The rising Death Toll

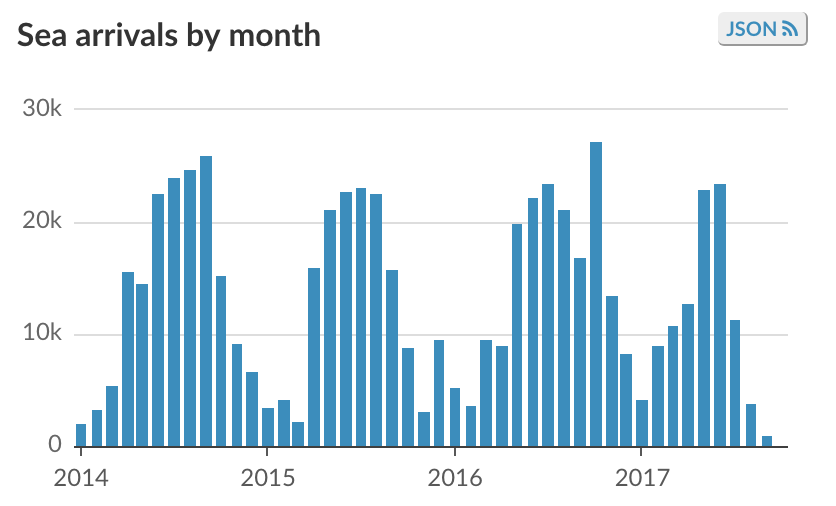

In autumn 2015, the number of crossings through the central Mediterranean route dropped due to weather conditions and the opening of the Balkan-Route by refugees. This drop in numbers was not the result of a “successful fight against smugglers”. This was evident when the figures rose to 10,000 people again by early December. Over the Christmas days alone, more than 2,200 refugees were saved.

Beginning in February 2016, the borders along the Balkan-Route were closed, one after the other, and on the 18th of March 2016, the EU-Turkey Deal was put into effect. As expected, the number of crossings from Libya to Italy started rising again. However, among the rescued refugees only few were from Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan, meaning only few were from the group of refugees, who were trying to get to Europe along the Balkan-Route. The vast majority of crossings from Libya was and still is from East and West Africa as well as from Bangladesh.

The Alarm Phone received many calls from travellers in distress on the Central Mediterranean route. In many cases Mussie Zerai, an Eritrean Priest, who lives in Europe, put them and us in touch with each other. In light of a continually rising death toll and stricter EU deterrence measures, we started the campaign “ferries for all” in spring 2016.[2] The Alarm Phone also took part in actions to commemorate the deaths of over 1.200 people, who had drowned at sea during one week in April 2015. One year later, on the 18th of April 2016, more than 500 people drowned near the Italian coast. Their boat had capsized as passengers were trying to board another boat.[3]

The Alarm Phone was involved in a similar case on the 26th of May 2016: Refugees on three boats started getting into distress in the southern Mediterranean. The boat, from which we received the call, was carrying more than 500 people and was towing the two other boats. One of these boats, also carrying around 500 people, had already started to capsize. Some managed to swim to one of the undamaged boats, while others managed to stay afloat until rescue came. However, due to the delayed reaction of the coast guard, more than 400 people drowned.[4]

On the 29th of August 2016 alone, more than 5,500 people were rescued. Some had fled from Morocco to Libya to try to reach Italy. During an Alarm Phone meeting in Tangier in September 2016, we discussed the situation and the difficulties of the land route between Sub-Sahara Africa and Libya with people who had fled from there. We also started considering the possibility of setting up an “Alarm Phone Sahara” – a type of emergency phone for refugees traveling from West Africa to Libya through the desert (see article in this brochure).

Funding Violence

In contrast to the previous years, autumn 2016 witnessed an increase in crossings from Libya to Italy. In October alone, the number of refugees reached a peak at 27,384, and many fatalities brought the death toll up to one thousand in only one month. As a result, the Alarm Phone intensified its cooperation with some of the SAR-NGOs. Together, we demanded not only an expansion of rescue operations, but more importantly, safe and legal passages to Europe for all. Moreover, in light of the increasing attacks on SAR-NGOs, coordinated action has become evermore important.

In the night of the 21st of October 2016, a rescue operation of Sea Watch 2 was disrupted by a boat of the so-called Libyan coast guard. Members of the Libyan crew jumped onto the overcrowded refugee boat and started attacking the passengers, causing mass panic. Most of the 150 passengers fell into the water, around 30 of them drowned.[5] In August 2016, there had already been an attack on a rescue boat from MSF (Doctors without Borders) and in September the same year, two Sea-Eye crew members were temporarily arrested by the Libyan militia.

Around the same time, on the 26th of October 2016, two boats from the EUNAVFOR Med-Operation Sophia started a three-month training programme for 78 members of a Libyan coast guard unit, which is under the direct authority of the Sarraj government in Tripoli. Their officially stated goal is to enable the Libyan coast guard to secure their territorial waters. In reality, however, they want to ensure that refugees are caught right off the coast of Libya and brought back to land. EU boats are not allowed to do this thus far.

In the same month, German Chancellor Merkel went to Mali, Niger and Ethiopia on her ‘Africa Tour’. Her official goal was to combat the ‘root causes of migration’ and she promised, amongst others, the government of Niger 27 million euros to combat “irregular migration.” In the following months, a number of vehicles were confiscated and alleged smugglers detained. For the refugees, these measures meant that they had to take even riskier routes through the desert, while the prices smugglers were demanding increased.

The Situation in Libya

In January 2017, members of the Alarm Phone met with some SAR-NGOs and activists from Libya in Tunis. The political and economic situation in Libya has further deteriorated due to fights between the opposing governments and the different militias. Violent clashes are part of everyday life. Smuggling humans and goods, exploiting migrants and organising sea crossings in overcrowded, sea-unworthy boats have become the only lucrative source of income for many Libyans. Sometimes, different fractions of the Libyan coast guard cooperate with smugglers and militia, making it difficult for SAR-NGOs to know whom they are dealing with at sea.

The Alarm Phone has also received distress calls from migrants stuck in Libya, but unfortunately, it is nearly impossible to support them; even large humanitarian organisations cannot work there without risking the lives of their members. And although the IOM organises the repatriation of refugees to their countries of origin from Libya, the streets are generally too dangerous to actually pass through. For refugees, there is a high risk of being abducted and detained in camps, where people are abused, extorted and even killed. The German embassy in Niger’s Capital Niamey reported in a diplomatic report (“Drahtbericht”) of extremely serious and systematic human rights violations in Libya. Authentic photos and videos of the so-called private prisons in Libya show, following their account, conditions similar to those in concentration camps.[6] The refugees are thus often left with only one choice: to put their lives in the hands of smugglers and try to reach Europe by sea. One rescued refugee on board of the Iuventa, the rescue boat from the German organisation Jugend Rettet, said: “We knew that we might die, but we didn’t care; we could not stay in Libya a second longer.”

Nevertheless, a declaration was adopted at an EU Meeting in Malta on the 3rd of February 2017, which set out, inter alia, to create “adequate reception capacities and conditions in Libya for migrants.”[7] So far, systematic push back operations have still failed, due to the lack of unity within the Libyan government. Moreover, the proposal by the EU to bring the refugees, who are intercepted right in front of the Libyan coast to camps in Tunisia, Egypt or even Algeria and Morocco, was rejected by the respective governments. Together with activists in these countries, we must put continuous pressure on the authorities and make use of their diverging interests: The corrupt leaders of African countries of transit and origin are interested in EU resources and in the remittances from refugees, who have reached Europe. They are, however, not interested in accepting numerous intercepted refugees, mostly from other countries of origin.

Criminalisation of SAR-NGOs and insufficient State Rescue Capacities

In an interview with welt.de in February 2017, Frontex director Fabrice Leggeri, once again, launched a campaign to criminalize SAR-NGOs. He accused them of colluding with smugglers, and said that “we” have to make sure that “we” do not support the businesses of criminal networks and smugglers in Libya by allowing European boats to “pick up” migrants closer and closer to the Libyan coast.[8] In response to this, the SAR-NGOs and Alarm Phone issued a joint statement rejecting these allegations: “People do not migrate because there are smuggling networks. Smuggling networks exist, because people have to flee. Only safe and legal routes to Europe can put an end to the traffickers’ business.”[9]

At the Alarm Phone meeting in Palermo in March 2017, discussions with affected persons from West Africa helped us to gain a better understanding of the dangers and risks refugees face on the route to and through Libya. They explained that it is nearly impossible to make calls from a boat in distress: either their phones are confiscated while detained in Libya or at the latest right before they get on the boat. The few who manage to bring a satellite phone on board, usually don’t know how to use it. It has become increasingly difficult for refugees to have any influence on the conditions of their crossing. They are forced – sometimes at gunpoint – onto completely overcrowded boats, without life vests and without sufficient fuel and food. These boats rarely make it out of the Libyan SAR-zone into international waters, not to mention all the way to Italy.

In light of these growing numbers of boat departures from Libya in spring 2017, the lack of state rescue capacities has become more and more evident. NGOs often had to conduct rescue operations on their own. On the Easter weekend, the Iuventa had taken in so many refugees that they could not navigate the boat anymore and needed to signal MAYDAY. Only after several hours, other civil rescue boats and Moonbird – a joint aircraft from Sea Watch and the Humanitarian Pilots Initiative – came to help (see article “Particularly Memorable Alarm Phone Cases”). Neither Frontex nor EUNAVFOR Med were seen in the area, whose absence was criticized by the NGOs. This, bizarrely, not only led Frontex to claim that they had never criticized civil rescue organisations, but even to demand legal passages to the EU.[10]

Italy’s Demands

In May and June 2017, the number of crossings in the Central Mediterranean increased to over 23,000 per month. From January 2017 until the end of July, nearly 100,000 refugees arrived in Italy. In light of this, Italy demanded that EUNAVFOR Med change its deployment directive: other European ports should also accept refugee boats. Instead, however, a joint statement by the EU commissioner Avramopoulos and the French, German and Italian Ministers for Internal Affairs was released on the 3rd of July 2017, in which they demanded more support for the Libyan coast guard, more border controls at the southern borders of Libya, more deportations with the help of Frontex and a Code of Conduct for SAR-NGOs. The Code of Conduct forbids, inter alia, the transfer of rescued refugees onto another boat and requires the toleration of armed police on board the rescue boats. On the 25th of July 2017, the EU decided to prolong EUNAVFOR Med’s mission until the 31st of December 2018. Italy was satisfied with an additional 100 million euros for the admission of refugees and 500 deployed officers, who would speed up the asylum and the extradition procedures in Italy.

Great confusion was caused by a plea from the EU-recognised West Libyan government of Sarraj. He asked for a military operation in Libyan waters, which was to start on the 1st of August 2017. Sarraj’s opponent, Field Marshal Khalifa Haftar, in the East of Libya, accused him of compromising Libya’s sovereignty and threatened to attack all boats that were to enter Libyan waters without his permission. Nonetheless, on the 2nd of August 2017, the Italian parliament agreed to the mission and sent out their first boat, which was, however, only allowed to sail in waters near Tripoli. The crew was also not allowed to return refugees to Libya, but would have to hand them over to the Libyan coast guard. With the prospect of receiving more money from the EU, the Libyan coast guard allegedly brought over one thousand refugees back to Libya within just a few days, in early August.[11]

Right Wing Activities and State Repression

Radical right wing activists from the Identitarian movement started a campaign against SAR-NGOs at sea in spring 2017. They chartered a boat, the C-Star, and announced that they would attack civil rescue boats. After powerful protests by human rights and refugee organisations, they changed their strategy, declaring that they would intercept refugees in front of the Libyan coast to hand them over to the Libyans. Egyptian, Cypriot and Sicilian authorities were only able to temporarily disrupt the operation and on the 6th of August 2017, Tunisian fishermen, union members and human rights organisations were able to prevent the docking and refuelling of the C-Star in Tunisian ports. The C-Star still managed to reach the Libyan coast and requested the SAR-NGOs to leave the zone, but shortly after entered a situation of distress itself, though rejecting to be rescued by the NGO Sea-Eye.[12]

Around the same time, state repression against SAR-NGOs increased. After futile negotiations with the Italian government in July 2017, some NGOs refused to sign the Code of Conduct, even though they feared being denied entry to Italian harbours to disembark refugees.[13] SOS Mediterranée signed the Code of Conduct after the Italian Ministry of Interior accepted to add a clause restricting the code’s influence.[14] On the 2nd of August 2017, the Iuventa was confiscated by the Italian authorities, due to a preliminary investigation brought about by the public prosecutor’s office in Trapani that is accusing the crew of facilitating illegal entry into Italy. The Alarm Phone and other organisations and activists continue to show solidarity with Jugend Rettet.

In mid-August, the Libyan coast guard fired warning shots towards the boat from Proactiva Open Arms, declared their own SAR-zone far beyond their territorial waters and warned the NGOs of entering this extended zone in the future. Given these circumstances, MSF, Jugend Rettet and Sea-Eye felt that the safety of their crews could not be ensured any longer and suspended their sea rescue missions on the 13th of August 2017. Two days later, some armed Libyans intercepted the Golfo Azzurro and threatened the crew for over two hours. There is great reason to fear the complete exclusion of NGOs from the SAR-zone off the Libyan coast. The EU Commission announced that an expansion of their military operation Triton would compensate for the withdrawal of NGOs.[15]

This criminalisation campaign against SAR-NGOs is intended to have a detrimental effect on the financial and public support that the SAR-NGOs have received so far. The reactions of government agencies, however, show that we are, at the very least, disrupting their deterrence policies and practices. This highlights the importance of the work we do, connected across the Mediterranean. In their continuous attempts to deal with the symptoms rather than the problem itself, the EU is not only investing in military and technology to close down the borders to Europe, but also collaborating with African governments to reduce the number of refugees fleeing to Europe. It continues to ignore, however, the actual reasons why people are fleeing from their countries of origin in the first place. None of these efforts will change anything about the migrants’ motivations to flee. Therefore, we must continue to monitor, document, publicise, criticise and intervene at sea, in political debates, and with direct actions. It is the only way we can assert legal and safe passages and avert deaths.

[This text is part of the recently published Alarm Phone brochure “In solidarity with migrants at sea!]

[1] The smugglers are usually not sitting in the boats, instead, one of the refugees is appointed to drive the boat and is criminalized later.

[2] https:/ Alarmphone.org/en/2016/02/12/newspaper-ferries-for-all/?post_type_release_type=post

[3] https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/apr/20/hundreds-feared-dead-in-migrant-shipwreck-off-libya

[4] http://watchthemed.net/reports/view/514

[5] http://watchthemed.net/reports/view/588

[6] https://www.welt.de/politik/deutschland/article161611324/Auswaertiges-Amt-kritisiert-KZ-aehnliche-Verhaeltnisse.html

[7] http://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/meetings/european-council/2017/02/03-informal-meeting/

[8] https://www.welt.de/politik/deutschland/article162394787/Rettungseinsaetze-vor-Libyen-muessen-auf-den-Pruefstand.html

[9] https://Alarm Phone.org/en/2017/03/03/european-civil-rescue-organizations-stand-up-against-smuggling-allegations/

[10] http://www.heute.de/fluechtlingsdrama-auf-dem-mittelmeer-frontex-fordert-legale-einreisewege-nach-europa-47015858.html

[11] http://www.faz.net/agenturmeldungen/dpa/kuestenwache-bringt-migranten-zurueck-nach-libyen-15140721.html

[12] https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/aug/11/migrant-rescue-ship-sails-to-aid-of-stranded-far-right-activists

[13] https://www.timesofmalta.com/articles/view/20170808/local/stranded-rescue-vessel-heads-north-towards-sicily.655216 – They were only allowed to enter the harbor, when they had problems with their engine..

[14] http://sosmediterranee.org/sos-mediterranee-unterzeichnet-verhaltenskodex/

[15] https://www.woz.ch/1733/seenotrettung/eskalation-auf-hoher-see