1 Introduction

Sunk boat in the harbour of Arguineguin, Gran Canaria. Source: Alarm Phone, 2022

Sunk boat in the harbour of Arguineguin, Gran Canaria. Source: Alarm Phone, 2022

The past few years have seen a huge shift of crossings from the North of Morocco to the South of the country and to Western Sahara. Accordingly, anybody involved in the underlying business structures also extended their networks south. However, the change is not only geographical but also substantial in nature. Before the militarisation of the northern borders reached its peak in 2019, crossings were organised in a fairly de-centralised or collective manner. A group of friends would get together to buy a rubber dinghy to cross the Strait of Gibraltar or larger groups of people would organise jumps of the fences in Melilla and Ceuta. This securitisation – orchestrated by the European Union – of the northern borders has deprived travellers of such horizontal ways of organising. They now have to rely on increasingly centralised smuggling networks. Not only has this militarisation thus promoted more hierarchical networks, but it has also reduced the number of routes available to travellers. This results in an increased demand on the few remaining routes on offer and, thus, low-quality products flood the market. That is to say, people are sold trips which use bad equipment or set off in adverse weather conditions. It increases the death rate. This phenomenon is exemplified by the current prevelance of rubber dinghies being sent on the Atlantic route for instance.

Alarm Phone members from Morocco also describe how prices have shot up from a couple of hundred euro to several thousand, even up to €5000 for a journey. The fact that people are willing to pay these prices shows how desparate they are and that the European Union’s discourse that blames migrants for relying on smugglers is bonkers: why would anybody chose to pay €2000 if a visa was available for €200, a tenth of the price? People do not “chose” to pay smugglers – they do not have any other option.

Another misconception in how these business networks are portrayed is their focus on the “smugglers” as the core of the problem. As this analysis shows across different regions, this kind of border business would not be possible without deep-seated state corruption. Bribes must be paid to the Moroccan auxiliary police who patrol the coastline, but for some travel options (notably, the so-called “VIP trips”) the Moroccan Navy is also paid not to intercept. Spanish state officials also have a reputation among travellers for receiving bribes, especially at the border crossings to the enclaves – a business sector that has collapsed in the last two years because of the Covid-19 related closure of the land borders. Smuggling networks extend to both sides of the border and involve the local population, local companies and authorities on both sides of the sea. And let us not forget that the biggest beneficiary of the border business has always been and will always be the European economy. Without the cheap migrant labour workforce, who would work the fields in southern Europe, clean the toilets and stock the warehouses?

As Alarm Phone, we have a more nuanced understanding of the so-called smugglers. Over the years we have encountered a variety of very different people in the border business: people who earn money organising boat journeys because they do not have any other reliable source of income, people who even organise free trips on boats for vulnerable people (e.g. women and children) out of solidarity, but also people who actually brutally exploit the need of others in order to enrich themselves. This is why we do not speak of “smugglers” but choose more nuanced terms. Within the traveller communities themselves, the organisers are called “Chairmen” since it is often individuals with a preeminent position in their respective community who, in addition to their role as a community organiser, run a sort of travel agency. Yes, there are smugglers and we should not hesitate to name them as such and denounce exploitative practices where we come across them. But there have always been some travel agents who try their best to provide a much-needed service. For this reason, we use the three designations (smuggler, travel agent, chairman) mentioned in this report, depending on the context.

The following report sheds light on how this border business works in different regions in the Western Mediterranean and on the Atlantic route. We hope that it will underline that the problem of the border business does not consist in the individual smugglers and travel agents. The reason for the flourishing border business are a) the racist border policies of the European Union that do not offer any regular route, militarise borders and push migrants to resort to centralised and often exploitative smuggling networks and, closely intertwined, b) the capitalist structures in which state officials and local populations enrich themselves and the European economies thrives.

2 News from the regions

2.1 The Atlantic Route

Border business between Western Sahara, Morocco and the Canary Islands

Business on the Atlantic route has soared in recent years. This is a direct result of the closure of the northern routes. Smugglers and travel agents who previously worked in the North have now set themselves up in Western Sahara: “Nowadays, there are many more chairmen than in 2019. Since a lot has changed in Tangier and Nador, the chairmen working there have now come here [Western Sahara] and some intermediaries have also become chairmen”, explains A. from Alarm Phone Maroc.

These smugglers and travel agents have also brought their recruiting networks. Many passengers leaving from Western Sahara or the south of Morocco do not actually live there, they remain in camps and migrant neighbourhoods in Tangier, Casablanca, Nador etc and only travel to the south a few days before their departure. Passengers are recruited by word of mouth. These tend to be sub-Saharans fresh off the plane from their countries of origin, those living in the aforementioned cities, or Moroccan travellers, especially those from poorer regions. The smugglers and travel agents themselves also do not live close to the places of departure. They have their apartments elsewhere.

Because of the huge spike in demand since 2020, profit margins for smugglers have multiplied. In a rare interview with the newspaper La Vanguardia, one Moroccan travel agent tells us that he made €70,000 within just two months. The increase in demand, however, also results in dodgy operators selling services below the already less-than adequate, life threatening quality of the options already on the market. As Alarm Phone activist B. explains, “at the same time, passengers are more frequently ripped off by bad organisation, and these ill-prepared trips result in many deaths and missing boats”.

Although it depends on the equipment provided by the travel agents (wooden boats, fibre or aluminium hulls, navigational devices and so on), according to one travel agent, around €20,000 have to be spent per trip for the equipment and fuel. An additional €10,000 are often needed to bribe state officials. A., an activist from Laayoune explains how smugglers work together with corruptible state authorities:

“The boats that are leaving from here, Laayoune or Tarfaya, you need to pay the coastguards, the military police. If you don’t, you can’t find a departure spot because every two kilometers, there is a control post. The Moroccans who work with the [sub-Saharan] smugglers are going to arrange for the police to be paid so that they will turn their back on migrants embarking on a boat.”

If passengers are able to pay a higher price, a so-called VIP trip (usually between €3000 and €5000), they are able to embark on a journey with higher bribes, preventing interception not only at the shores but also further out at sea. The standard traveller currently pays between €2000 and €2500 for a seat in a boat. If they want to buy several attempts with one payment (the so called “guaranteed” version), the price is higher, €3000 or more.

However, the dense network of corruption between well-remunerated smugglers and state officials extends much further than boat departures. When smugglers are arrested, they are usually sentenced to between 5 and 20 years of prison. Yet, for the wealthy different rules apply. Sumgglers can pay a large bribe and leave prison after just a few months. It means that the travel agents actually serving their prison sentence are usually small fry. It’s worth noting what the travel agent from Dakhla interviewed by La Vanguardia had to say:

“For the police and for us “smugglers”, migration is of interest. We earn money together. Every two or three months, they arrest a smuggler to show they are doing their job, but I’m not scared, I have good contacts.”

Naturally, these networks are not limited just to the (military) police and smugglers. Recently, a member of staff of the Caritas Meknes has been accused of participating in a smuggling network and of having had significants sums of money deposited in his private bank account over the last few years. Needless to say, corruption is rampant on both sides of the sea, with local residents being part of smuggling networks operating on the Canary Islands. This is well illustrated by the case of abandoned boats and engines in the harbour of Arguineguin, Gran Canaria. Once boats have been towed to port by Salvamento Maritimo, engines and fuel are stolen to be resold for €300 and then exported back to Mauritania and Senegal through Spanish small business, e.g. those dealing in electronics and appliances, and then sold in the countries of departure for up to €4000. In early October, one such network comprising workers of the local business managing Arguineguin harbour and the local population from neighbouring towns was dismantled by the Spanish authorities after they had discovered a container with 52 engines. For a long time, the local authorities did not deal with these abandoned boats and engines, leaving them to accumulate in a kind of boat cemetery. Last autumn, the Ministry of the Interior sub-contracted a company to destroy these boats. Since then they have disposed of little more than 100 of these boats for the price of €60,000.

When we talk about border business on the Atlantic route, we cannot ignore the boats which carry drugs. These are a very lucrative part of the business model for smuggling networks in Morocco and Spain. However, these boats, which usually arrive in Lanzarote, never contact Alarm Phone and we will therefore not include them in this analysis.

Crossings & Rescue: an invisible wall in the Atlantic

The new year has seen yet another increase in crossings and arrivals. For the whole Western Mediterranean and Atlantic region, 7430 people successfully crossed in January and February. This compares to 3915 arrivals in the same period in 2021. The jump in arrivals is most pronounced on the Canary Route where the arrival of 5604 people so far this year constitutes an increase of 119% over the first two months of 2021.

As we can see from these numbers, journeys to the Canary Islands constitute 3/4 of all arrivals to Spain. The Atlantic route remains the most lethal route to Europe, with estimates of more than 4404 dead and missing in 2021, according to the collective Caminando Fronteras. Big shipwrecks keep happening for the same reasons we have detailed in previous reports. For instance, boats get lost at sea and disappear completely (such as the 52 people who left Tarfaya on 04 January or the 60 people who also left in the first week of January) or, by fluke, get picked up in extremely remote places (for example the Gambian boat with 105 survivors and 17 dead that got picked up 800 km south of the Canaries after 19 days at sea in December or the 34 people that had left Dakhla on 03 November, with only 20 people surviving the three weeks at sea). Another reason is that many boats encounter problems shortly after leaving the Moroccan or Saharan shores. The latter is a result of the trip organisers using faulty material or simply ignoring the weather forecast. For example, we see many cases of pierced rubber boats or engine failure.

Both problems are compounded by the indifference of the authorities. In several instances, Alarm Phone alerted the Moroccan authorities right away but rescue was delayed for hours, resulting in horrific tragedies. We mourn the 45 who died (43 drowned, 2 died in hospital) when the Moroccan navy did not respond to a shipwreck with 53 people on 16 January and the four people that were left to drown on 06 February, because MRCC Madrid delegated responsibility to Rabat who failed to organise a timely rescue.

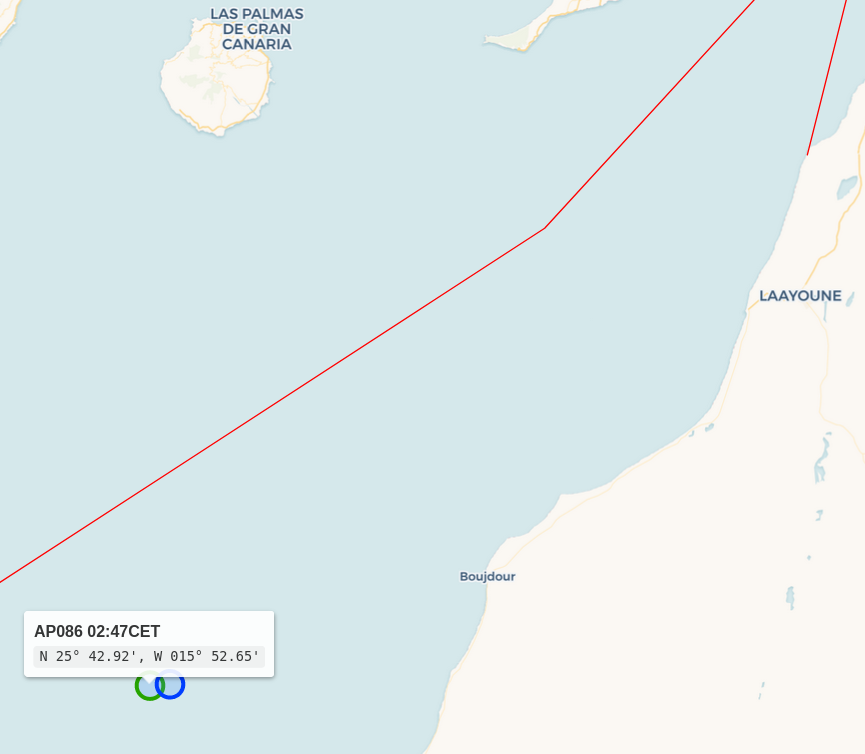

This latter case highlights a very troubling political development in the Atlantic: the creation of an invisible wall at sea. As Alarm Phone, we can see a tendency for more and more SAR operations to be delegated to the Moroccan authorities, although boats are in the overlapping SAR zone. By treating boats in a zone with both Spanish and de facto Moroccan responsibility as being Rabat’s problem, the Spanish state is, in fact, pursuing an ‘interception where possible’ policy. This may be a reaction to the increasing provision of satellite phones by the travel agents. Since last summer, more and more boats have been equipped with these devices. With a satellite phone, travellers are able to call the authorities and Alarm Phone from the sea with their exact GPS position. In several cases however, when this GPS position was within the SAR zone for which Morocco also claims responsibility as part of their occupation of the Western Sahara, an interception was organised jointly by Spanish and Moroccan authorities.

Alarm Phone case on February 6th: Despite the GPS position being in the overlapping (and thus also Spanish) zone of responsibility, MRCC Madrid delegated responsibility to Rabat who failed to coordinate a timely rescue. Four people lost their lives. Source: Alarm Phone, 2022

Alarm Phone case on February 6th: Despite the GPS position being in the overlapping (and thus also Spanish) zone of responsibility, MRCC Madrid delegated responsibility to Rabat who failed to coordinate a timely rescue. Four people lost their lives. Source: Alarm Phone, 2022

The creation of this invisible wall is not the only worrisome development. The Atlantic Route is also being extended to the North. Some Moroccan communities have started organising departures from cities as far north as Al Jadida (near Casablanca). This makes for a 650km journey south to Lanzarote. Correspondingly, in this period some rescues happened far north of the Canaries, such as 35 people rescued 210km North-East of Lanzarote on 18 January.

Boats also still leave from further south, but less often than in late 2020. In 2021, 55% of all boats which arrived on the Canary Islands had left from Western Sahara, another 26% from southern Morocco, e.g. from Tan-Tan or Guelmim. It also corresponds to a drop in the percentage of journeys from countries to the South. Now only a fifth of all arrivals are boats leaving from Mauritania, Gambia, Senegal. Most departures happen somewhere between Boujdour and Tan-Tan, which explains the very high proportion of arrivals to the eastern Canary Islands. Lanzarote, Fuerteventura and Gran Canaria receive almost all of the arrivals. Half of all travellers are Moroccan nationals, followed by Guinea, Senegal, Ivory Coast. For Moroccan travellers, deportations resumed after Morocco re-opened its borders in early February.

Facilities for reception on Lanzarote are notoriously overwhelmed. Taking more rescued boats to Arguineguin harbour in Gran Canaria and transferring migrants to Fuerteventura can only do so much. Until very recently, upon arrival in Arrecife harbour, travellers would get taken to an industrial building some kilometers outside of the city and allocated some space in this former industrial warehouse. People were held for a 72 hour quarentine period and Covid-19 testing. Conditions were sub-human, no proper beds, no privacy, no showers and no safe spaces for minors and women. Activists and human rights defenders campaigned against the “nave de la vergüenza”, the “warehouse of shame” and complained about the inhumane conditions to the authorities and to the ombudsman, who in turn called for the closure of the space. Just as we were finalising this regional analysis, the Ministry of the Interior announced that the “nave” had been emptied and newcomers would be taken to the temporary accommodation centre (CETI in Spanish) just across the road. It remains to be seen whether this will result in a substantial change and decent accommodation.

“La Nave” – the warehouse outside of Arrecife (Lanzarote) where, until very recently, new arrivals were detained in inhuman conditions. Source: Alarm Phone, 2022

“La Nave” – the warehouse outside of Arrecife (Lanzarote) where, until very recently, new arrivals were detained in inhuman conditions. Source: Alarm Phone, 2022

2.2 Tangier, Ceuta and the Strait of Gibraltar: A decrease of departures

The increase in crossings to the Canary Islands has gone hand in hand with a decrease in attempts from Tangier, a route which used to be well travelled. Around 5 years ago, every one or two months, we would still hear about the Boza (success) of 1 to 2 boats. But since then, with Covid-19 and, in addition to that, the closing of the borders, we do not hear much about Boza in Tangier.

In the period of this report, Alarm Phone only dealt with 3 cases around Tangier. On 05 November, seven people in distress East of Tangier returned to Morocco autonomously. On 09 November, a boat with 13 people (including 1 woman) was intercepted by Marine Royale and on 12 December another 3 people were intercepted. The only case in the beginning of 2022, however, turned out to be a Boza. On 10 January, Alarm Phone was informed about 3 people who had left from Fnideq close to Ceuta in a plastic kayak. Water was entering the boat. Alarm Phone informed the authorities but lost contact to the boat. The next day, the union CGT Salvamento Maritimo announced that three Moroccans were rescued and taken to Algeciras.

One of the main reasons for the scarcity of departures and even greater scarity of sucesses lies in the fact that Moroccan authorities have reinforced security and ramped up the militarization of the border. Black people on the move live in a state of insecurity in Morocco as there are frequent attacks on people perceived to be migrants. Alarm Phone activist K. from Tanger reports:

“Daily life is full of problems and you are subject to massive repression. Day to day violations of human rights and arbitrary arrests leave you in a constant state of panic or anxiety. But the reality is that even in the face of all these policies, people do not despair and are still looking for ways and means to travel, but the situation is becoming more and more difficult for people on the move”.

It results in a loss of hope and leads many to move to Laayoune as attacks and arrests are not so frequent and it is still possible to make the crossing.

Moroccans who work in the organizations arranging onward travel in the North of the country are no longer very active because of the increase in the security and militarization of the borders. In the North, it is now just small groups of people who organise the trip, perhaps because of a lack of demand. Sometimes those who try to cross to Europe are intercepted by the Force Auxiliaire (Military Police) on land or by the Marine Royale at sea. When people are in distress or danger at sea, the Marine Royale is contacted, but it often happens that they don’t come in time.

From people on the move in Tangier we heard that the prices for the journeys from the North-West are variable, but it is obvious that the militarisation of the region has led to massive increase of prices and the professionalisation of border business. For self-organised small boats each person contributes between €150 and €250, although the price can be as much as €500 – €750. The prices depend on the size and quality of the material. But due to the massive militarisation of the border zone in Tanger it is now almost impossible to organise trips amongst friends. People are still making the crossing, but, because of the increase in border surveillence, travellers have become reliant on centralise structures and pay between €4,000 and €6,000 for the journey. This price is exhorbitant and shows that not only do the travellers have to organise big sums for themselves, but also that it provides a tidy profit for everyone involved in the business. The price represents a good payday for the smugglers of course, but they aren’t the only ones raking it in. When it comes to bribing the Marine Royale, for large groups the figures are enormous. The figures reported to us are in the range of €30,000 – €50,000 for boats with engines, but bribes can be as much as €70,000 – €100,000.

It is clear that the gains made through this absurd upgrade in military and policing are to the detriment of travellers: “It’s an absolute nonsense. It has become a living for many people. The EU and Morocco have made the movement of people a really profitable business” comments K. from Tangier.

2.3 North-Eastern Morocco: Ongoing repression in Nador region

The forests around Nador remain subject to frequent police raids, state repression and violence towards black people. As part of that repression, many sub-Saharan intermediaries have been arrested in the last few years.

Living conditions in the camps are far from safe. On 24 January they resulted in the death of 3 children. They choked to death after their makeshift tarpulin lean-to caught fire in the Gourougou forest (Northwest Cimetière Sidi Salem, Nador). Their mother, Happiness Johans, died in hospital a few days later. In response, AMDH Nador wrote an open letter to the Minister of Interior to demand that travellers should be allowed to rent houses in Nador.

Nador is not only a gathering point for sub-Saharan traveller communities, but also a point of departure for Moroccan nationals heading for Spain. They also suffer from repression. The arrests and inhumane expulsions of Moroccan minors in Nador continue. AMDH Nador reports that on 01 January nearly 80 unaccompanied minors and young people were forced onto buses and taken to Casablanca. None of them were from that city.

Moroccan nationals continue to travel to mainland Spain via sea, but they organise very differently from the sub-Saharan travellers. The Rif region is no exception. Rather than professional outfits, it is friends who get together to plan and organise the crossing. They pool their resources to get the necessary equipment and, in some cases, to bribe the military officers who monitor the points of deperature. Friends and family members might also provide material support for the journey. As we don’t have further concrete insights on the way Moroccan nationals manage to overcome the border system, and likewise other communities, e.g. Syrian and Yemeni nationals, we can only describe the way sub-Saharan travellers pass through Nador.

The border business around Nador: Prices have risen dramatically

The system established around the passage to Europe via Nador has seen fundamental changes throughout the years. Prices have risen dramatically for journeys from the Nador region. One local Alarm Phone member who has been living in the forests of Nador since 2001, remembers that until 2010, you could get a spot in a boat for as little as €300. Then, between 2010 to 2014, a new system evolved in the forests: the ‘guarentee’ system People now travel with ‘guarentee’. They make a higher, one-time payment but are guarenteed as many crossing attempts as it takes to reach Europe. This is perhaps a response to the high interception rates on both land and sea. It now often takes several attempts in order to cross succesfully. The ‘guarantee’ price went up to €1500. Around 2018, prices went up to as high as €3500 and for a woman with kids up to €4500.

To understand how prices are determined in the forests one needs to know that negotiations take place through intermediaries within the sub-Saharan communities. These go-betweens meet regularly with the presidents of the different sub-Saharan communities. They also work with Moroccan boat organisers. The Moroccan agent demands a sum per head from the intermediaries for organising the boats. This is paid by the would be passenger, who must also pay commission to the go-between.

The agent and the intermediary negotiate the price per head. United the travellers could exert a good deal of leverage over the agents in these negotiations, as the Moroccans have no other link to their would be clients. But, the law of supply and demand favours the smugglers. Travel opportunities, seats in the inflatable dinghies, have been scarce for a few years now and some sub-Saharan communites agreed to pay higher sums to the Moroccan smugglers in order to secure their spots. This has resulted in a global price rise. It is a very profitable business for the travel agents.

Confronted with exhorbitant price rises for journeys, we are told that communities have tried to organise themselves to exert pressure to lower prices. However, unlike in a state governed by the rule of law where a consumers’ union could have kept prices at an affordable level, the criminalisation of the business has left buyers at the mercy of an absolutely unregulated market. In a situation where the client must pay up or stay put and get beaten up, the seller has all the power. Unsurprisingly, collective bargining across disperate consumer groups has failed. A single would be traveller can now pay up to €2600 to the smuggler and €900 in commission to the go-between for a seat in a boat along with 59 other travellers.

The presidents of the communities together with the intermediaries have always had a list of people that were living in the forests and didn’t have any means to pay for the trip, i.e. single mothers, but also others with no way to gather money. The presidents would keep a note of those ‘that never caused problems’ in the camps, that is to say peope who followed the camps’ codes and rules designed to ensure a safe life in the community. Slowly, slowly over the years spots were found for these people on the boats for free. Now that prices have gone up to such an extent that a would be passenger has to pay as much as €3500, such solidarity is no longer feasible. The situation of people without means has become hopeless. The only way that remains for them to reach Spain is to jump the fences of Melilla – an option that (with few exceptions) is only open to men.

Around Christmas and New Year’s Eve there were many collective attempts to jump the fences into Melilla. The attempts were met with violence by the Spanish and Moroccan authorities. According to the Spanish minister of foreign affairs, more than 1000 people trying to cross the fences into Ceuta and Melilla were intercepted in this short period. The border fences in Melilla are being further militarized. Armed military units are now permanently present. Nevertheless, on 02 March, as we were editing the current report, 2500 people managed to organise and attempt to jump these fences. Around 500 people managed to reach Melilla. This is a huge Boza. In terms of arrivals, it is one of the most succesful attempt on the fences at Melilla. Welcome to Spain!

Alarm Phone cases in the past months: 27 people disappeared without trace

In the time period of this report, 16 boats which had embarked from North-Eastern Morocco reached out to the Alarm Phone. 7 out of 8 boats that left in November and December 2021 between Temsamane/Al Hoceïma and Nador were Bozas to Motríl and Almería. Only one boat, carrying 15 people, was intercepted by Marine Royale. In the very first week of January, Alarm Phone was involved in two cases; one boat from Tazaghine returned to Morocco, another boat from Nador with 13 travellers was rescued to Almería.

On 08 January, Alarm Phone was informed about a boat with around 36 people which had left Nador during the night. MRCC Rabat later confirmed that they had intercepted the boat. Very sadly, another boat, which had left just a few hours afterwards from Nador, disappeared without a trace along with all 27 people who were on board. The passengers included 9 women.

In February, two boats which had contacted Alarm Phone after their depature from Al Hoceïma were rescued to Spain, another one was intercepted by the Marine Royale. On 12 February, Alarm Phone was informed about a boat with 7 people which had gone missing in the Alborán Sea shortly after its departure from Boufayar in the early morning. It took two days and lots of pressure from relatives and the Alarm Phone for it to be possible to figure out that the travellers had been rescued, taken to Motríl and immediately detained. As we tweeted in regards to this case, “we condemn the authorities’ silence as structural racism against people on the move. #FreedomOfMovement.”

2.4 Oujda and the Algerian Borderzone: crossings become more dangerous

The situation in Oujda and at the Algerian-Moroccan border remains precarious and has worsened in recent weeks. In the last four months, there have been arrests of people asking for money, including minors, and repeated push-backs to the border.

Many people who want to cross the border from Morocco to Europe have to pass through Algeria before doing so. Since this border has long been closed, even for people with official travel documents, it is of course extremely difficult to cross for people without such permission. And difficult almost always means expensive. Historically, men have paid between 150 and 200 euros, sometimes even €250 to cross the landborder from Algeria to Morocco. Women have to pay between 300 and 400 euros and (physically) disabled and sick people €500.

On 05 January, Morocco officially established a military zone on the border with Algeria. Until then, Morocco was divided into two military zones, North and South. This creation of the third zone is due to the ever intensifying conflict between Morocco and Algeria. The border was strengthened and equipped with material and personnel. As a result, crossing the border has also become more expensive, and, recently, the number of people crossing the border has dropped sharply. Prices have doubled and in some cases even tripled. Prices now start at €250 for able bodied men, women double and people with (physical) disabilities and pregnant women triple, we have heard that sometimes people pay up to €1000. The prices depend on your physical abilities, particularly your ability to run and your stamina. Crossing the border is, in fact, now mostly associated with the transport of drugs and is done in cooperation with Moroccan military forces, who in turn profit financially. People are advised to have some money and a smartphone with them to buy their way out of going to prison if they are discovered.

People who want to cross are often exploited but, as they have no other options, are powerless to prevent it. Women are often raped at the border area and become pregnant or catch sexually transmitted diseases from the perpetrators. Many people die making the crossing. Others die after arrival as a result of the hardships. This is especially common in winter because people lack appropriate clothing for the weather or because they slip on the sodden ground and fall into the flooded border trench and drown. If someone dies while crossing the border, the person leading the group cannot call anyone for help, otherwise they will be sent to prison. Even afterwards, hardly anyone has the courage to report deaths in the border area and so people disappear without their death being recorded anywhere. After crossing the border, especially in winter, people suffer the physical consequences of this dangerous route. The crossing can last from 2 to 3 days, but sometimes up to a week.

Just as crossing the border has become more dangerous, people’s living arrangements have also changed. Whereas in the past people lived in larger groups in a more or less self-organised way, it’s now often a case of renting your owen bit of floor space in an overcrowded flat. When the police find out that large numbers of people are staying in one flat, they force their way in and arrest people without papers and deport them to Algeria at night. At the end of last year, for example, the police arrested 20 people in their homes. According to our information, seven people with valid papers were released, seven people were taken to the border area at night and three people were arrested for deprivation of liberty and trafficking.

The beginning of the year saw an increase in raids on people’s homes. Raids are concentrated in the migrant neighbourhoods of Andalous and Ben Mrah, where homes are being raided with increasing frequency. In January, 16 people were arrested for deprivation of liberty in Sidi Yahya, another neighbourhood of Oujda, and are currently in court.

As a result of measures to control Covid-19 , the ‘passe sanitaire’, the vaccination certificate in Morocco, has been introduced without which people cannot enter shops or use public transport. Access to the vaccine varies. We have heard of people without residency papers being vaccinated in Morocco if they can show the authorities a valid passport. Nevertheless, people who just crossed the border from Algeria or people without valid passports, can’t get a passe sanitaire. This means that they cannot travel easily. Travel costs are at least doubled so that drivers can hide them from the controls.

2.5 Algeria: Departures to Spain

The trend noted in previous reports continued in the period covered by this report. November 2021 to March 2022 saw ever-increasing numbers of departures of young men, families, and women from Algerian shores, a consequence of the backlash against the 2019 social movement, the resulting disillusionment and the economic hardship experienced by the vast majority of people in Algeria. This is a hardship that has only worsened with the Covid-19 pandemic.

On the political level, Algerian activists, syndicalists and anyone involved in the Hirak still face formidable repression. Recently several organisations and numerous individuals published a statement denouncing the criminalization of party political, trade union and grassroots organising by the Algerian authorities. The repression not only results in the exile of a large number of people from Algeria, but also makes it difficult to obtain information on the ground about the situation of travelers, as the threat of criminalisation silences many citizens and activists.

In an article published on the French website Mediapart, an Algerian man living in Spain asks: “Why are so many of us fleeing Algeria? Tebboune [the Algerian president] is getting treatment in Germany and I have to stay here and die?”

The failing healthcare system drives many people to leave the country. According to an article on the Algerian website algeriepartplus, “Algerian nationals are the largest group of non-French nationals asking for a visa to access treatment in French hospitals”

With this in mind, it comes as no surprise that the number of departures has remained very high since November, with some peaks during the period. For example, there was a burst of departures, widely covered in the Algerian media, between 30 December and 04 January. Up to 40 boats left from the Algerian coast for the Spanish Peninsula. From our past experience of higher numbers of departures around national holidays (for example around the Eid festival in Morocco), we assume that travel agents sent more boats around the new year celebrations. The Red Cross recorded 312 people in its offices in Almeria, half of whom had only arrived in the last 24 hours, between 31 December and 01 January, according to an article by Infomigrants.

If numerous boats reach the Spanish coasts with success, too many others suffer a tragic fate. According to the NGO Caminando Fronteras, no less than 169 Algerian harragas were reported missing in 2021 and the lifeless bodies of 22 of them were found by the Salvamento Maritimo. From 01 – 05 January, 30 Algerians died in their attempt to reach Europe. Our thoughts and hearts are, as always, with the families and loved ones of the deceased.

Our use of the term “tragic” should not hide the responsibility for these crimes. On the one hand there is the lack of social and economic opportunities offered by Algerian political structures, on the other hand the deliberate denial by European countries of any regular migration route as well as the militarization of borders. Combined these factors force people to invent and risk ever more dangerous paths to a liveable future.

Alarm Phone supporting Algerian travellers to Spain

In the last months, Alarm Phone has assisted with six boats leaving from Algeria in the direction of Spain (on 05 November, 20 December, 30 December, 11 and finally 13 February). One of them was a boat with 9 people who had departed from Capdur (Béjaïa) in the evening of 30 December and ended up stranded on the Isla del Congreso (Spain). They were eventually pushed back to Nador, Morocco. This is just one more example of the xenophobic offensive of European states against travelers, sometimes, as in the case of this push-back, in total disregard of the law.

Travelers from Algeria not only face the risk at sea, but, once on the European side, there is the growing threat of deportation. In mid-November, a meeting between the Algerian and Spanish interior ministers resulted in the Algerian government’s decision to release the equivalent of €6.4 million to finance the repatriation of Algerian Harragas in 2022. Since then, deportations have dramatically increased. On 20 February, about thirty Algerians were deported from Spain to Oran or Ghazaouet. A previous deportation had occurred on 01 February when more than 40 Algerians were forced out through the port of Almeria. According to a local contact in Oran, the risk of arrest and prosecution for deportees forcibly returned to Algeria is very high. This is part and parcel of the harsh criminalisation of the harragas by the Algerian state that we discussed in a previous report. The Spanish deportation procedure therefore adds yet another risk for people on the move and contributes to corruption in Algeria, since the only way out of jail for the deportees is to bribe someone.

Thriving Border business

Clearly, the general and ongoing unleashing of repressive policies against people on the move has created the conditions for the development of a prolific border business run by ever growing underground organizations. In an article titled “Algeria: Smuggling of migrants to Spain generated nearly 60 million euros in 2021” Jeune Afrique highlights a 2021 investigation by the Spanish police showing that “these networks now have a fleet of “water cabs”, boats with powerful 200 to 300 horsepower engines that can quickly reach the Spanish coast and make several trips per week.”

In Algeria, unlawful organisations involved in the border business have becomed increasingly powerful and structured. In 2020 observers had already noted a change in the modus operandi of travelers linked to the growing role of criminal organisations in organising the crossings. Traditionally, the exile of Algerian people was organised in a autonomous way. Groups of about 10 people would pool resources to finance a boat and an engine, and then properly prepare their trip before setting sail. In the three last years, militarisation and repression against travelers increased. This went hand in hand with the corruption of the border police. It made possible the development of powerful, black market organisations. These now dominate the market. Our contacts in Oran tell us that the organisation of clandestine passage as it has developed in Algeria relies heavily on systematic practices of corruption within the border police. In addition, autonomous departures are now very difficult if not impossible, because the smugglers carefully monitor the coasts and beaches, on the lookout for the departures of boats that are not part of their fleet.

This is, according to Mediapart, particularly notable in the Oran region, where the majority of departures have happened in the last few months. A fisherman from Oran recounts that “the navy is no longer able to cope. Even when they try to stop them, [the smugglers] manage to escape because their boats are faster. […] On some days, I have counted as many as 11 smugglers’ boats moored in the water“. According to researcher Nabila Mouassi, also cited in the Mediapart article, “the mafia works on an equal footing with the state.”

As for the price of the passage, “all teenagers in Oran and villages around can tell you the price” says a local contact in Oran. It ranges from €750 to €4000, depending on the type of boat, the quality of the motor, the provision of GPS/satellite phone, etc.

3 Shipwrecks and missing people

In the last four months, we counted more than 200 deaths and several hundred missing people in the Western Mediterranean region. Alarm Phone witnessed at least ten shipwrecks and cases of death due to a delay of rescue or non-assistance. These ‘left-to-die’ cases are so common an occurence that they must be understood as an integral part of the deadly border regime.

Despite all of the efforts to document the dead and missing, we can be sure that the real number of people who have died at sea in the attempt to reach the EU is much higher. We want to remember each one and commemorate each unknown victim in order to overcome the political system that killed them.

On 08 November 2021, a boat with Gambian and Sengalese nationals starts from The Gambia in an attempt to reach the Canary Islands. They are a group of about 165 people. After two days their relatives lose contact to them. They have not heard from them since. 35 of the passengers came from Gunjur. The village remains in shock and confusion. (source: AP)

On 11 November 2021, four dead bodies are recovered and three people are declared missing. The deceased had drowned close to the coast of Oued Cherrat, Skhirat, Morocco.

On 14 November, a boat is found approx. 40 miles South of Gran Canaria, Spain with seven dead bodies on board. The boat had spent at least six days at sea. An eighth person dies after rescue in the port of Arguineguin, Gran Canaria, Spain.

On 15 November, two people die in a drifting dinghy found south of Gran Canaria, Spain. There are 42 survivors.

On 18 November, a dead body is washed ashore at Nabak, 16km north of Dakhla, Western Sahara.

On 18 November, a boat with two dead bodies and 40 survivors is found adrift 216km South of Gran Canaria, Spain.

On 19 November, a dead body is found after a motorboat capsizes in the vicinity of the coast of Sarchal, Ceuta, Spain.

On 20 November, Mutassim Karim goes missing in his attempt to swim to Melilla, Spain. The NGO AMDH points to the Guardia Civil as the cause of death and demands the opening of an investigation into the disappearence.

On 23 November, a boat with 34 people is found by a merchant vessel 500km south of Gran Canaria. 14 people died and only 20 people survive after 3 weeks at sea.

On 25 November, a woman falls over board as a boat with 58 people is intercepted by the Moroccan Navy off the coast of Laayoune, Western Sahara. Another person had died before the interception.

On 26 November, two people die and four are missing after a dinghy capsizes South of Gran Canaria, Spain.

On 27 November, the death of two people is confirmed after a boat with 57 people capzises during a rescue operation southeast of Fuerteventura, Canary Islands, Spain. Four people remain missing.

On 27 November, two dead bodies are recovered at sea in Punta Leona and El Desnarigado-Sarchal, Ceuta, Spain.

On 30 November 2021, five minors – Ahmed, Tarik, Yahya, Alae y Brahim – are declared missing in the Strait of Gibraltar, Morocco. They had left Ceuta two weeks previsiously in a raft without an engine heading for the peninsula. There is still no news.

On 01 December 2021, at least 40 people die after a boat goes down off Tarfaya, Morocco.

On 02 December, the remains of a baby are found onboard a boat off the coast of Fuerteventura. The baby was part of a group of almost 300 people who were travelling in five boats to Fuerteventura, Spain. The Alarm Phone was told that a sixth boat had gone down not far from the beach of Tarfaya. 22 people are reported missing and 13 people are found dead.

On 06 December, a boat with 56 people onboard arrives in Gran Canaria, Spain. A baby, two women and a man die before they reach the island.

On 06 December, the remains of three people are washed ashore on the beach of Beni Chiker, Nador, Morocco most probably after an attempt to cross to Melilla.

On 06 December, a boat with 20 people is rescued South of La Gomera, Spain. One dead body is recovered.

On 08 December, 29 people die after a boat capsizes in the Atlantic off Laayoune, Western Sahara. 31 people survive the shipwreck.

On 09 December, a dead body is found 50 km North of Dakhla, Western Sahara.

On 12 December, a dead body is washed ashore on the beach of Fnideq, Morocco. It is likely that of someone who tried to swim to Ceuta, Spain.

On 13 December, a dead body is found close to Sarchal beach, Ceuta, Spain.

On 14 December, a dead body is washed ashore on the municipal beach of Tangier, Morocco.

On 14 December, a dead body is found near the Corniche of Nador, Morocco. The person most probably died during his attempt to cross to Melilla, Spain.

On 17 December, one dead body is recovered on a boat with 60 people Southeast of Gran Canaria, Canary Islands, Spain.

On 18 December, 17 people die at sea between The Gambia and the Canary Islands, Spain. A boat with 105 survivors is found 800km south of Tenerife. The boat had left The Gambia 19 days earlier.

On 18 December, 35 die people die in the shipwreck of a boat carrying 52 people off the coast of Boujdour, Western Sahara.

On 20 December, two dead bodies are found near the Algerian border in Touissite, Jerada, Morocco.

On 21 December, a dead body is found at Playa de los Muertos, Almeria, Spain.

On 21 December, a boat with 15 people shipwrecks off the coast of Arzew, Algeria. Only eight people survive.

On 23 December, three people die and three are missing after a boat with ten people capsizes 3 km off the beach of Chlef, Mostaganem, Algeria.

On 23 December, two dead bodies are found in Ras Asfour, Jerada, Morocco (near the Algerian border).

On 28 December, the remains of two people are washed ashore at El Marsa, Chlef, Algeria.

On 30 December, a dead body is washed ashore on the beach of Ténès, Chlef, Algeria.

On 30 December, a dead body is found close to the port de Beni Haoua, Chlef, Algeria.

On 31 December, two dead bodies are found on the coast of Cherchell, Tipaza, Algeria.

On 31 December, a dead body is recovered at sea close to BouHaroun, Tipaza, Algeria.

On 31 December 2021, six survivors and three dead bodies are recovered after a shipwreck 35 nm off the coast of Almeria, Spain.

On 03 January 2022, three people die and ten people disappear in two shipwrecks off the coast of Cabo de Gata, Almería, Spain.

On 04 January, two boats with 103 survivors and two corpses are found by US naval vessels on manouevers in the Atlantic. The survivors are transfered to the Marine Royale.

On 04 January, Alarm Phone is informed about a missing boat with 52 people on board. The boat had left with 23 men, 21 women and eight children from Tarfaya, Morocco.

On 04 January, Alarm Phone is informed about a distress case with 63 people on board off the coast of Tarfaya, Morocco. Five people die at sea before rescue arrives and six people have to be treated in hospital.

On 07 January, after several days adrift, a boat is rescued after 26 km off the coast of Alicante, Spain. Five people can be rescued, at least 12 people are reported missing.

On 07 January, Alarm Phone is informed about a missing boat that had left Ain-El Turk, Algeria on 03 January with 12 people onboard. The boat seems to have gone down taking all the passengers with it.

On 08 January, Alarm Phone witnesses a shipwreck of a boat with 27 people on board off the coast of Nador, Morocco. The remains of five people are found close to Malaga, Spain 15 days later. 22 people are missing.

On 09 January, Alarm Phone Morocco is informed that a boat with 12 people on board has gone down off the Algerian coast. Only two people survive, ten people remain missing.

On 11 January, a dead body is found in the waters off Rocher Plat, Tipaza, Algeria.

On 12 January, the remains of one person are washed ashore at Plage Gounini, Tipaza, Algeria.

On 13 January, a boat with 60 travellors is lost. It had left a week previously heading for the Canary Islands, Spain.

On 14 January, ten people die in a shipwreck off the Algerian coast. Only three people can be rescued after 12 days adrift.

On 16 January, Alarm Phone is informed about a distress case with 55 people on board. When the rescue arrived only ten people were still alive and two bodies could be recovered. At least 43 people are missing. The shipwreck was close to Tarfaya, Morocco. It is reported that two people died in hospital.

On 16 January, the body of a young man is washed ashore on the eastern coast of Fuerteventura. The following day, the body of a yong woman is also found.

On 17 January, one person is found dead in one of the two inflatable boats rescued southeast of Gran Canaria, Spain.

On 16-25 January, five dead bodies are washed ashore on different beaches around Málaga, Spain:

- On 16 January, a dead body is found on the beach of Cabo Pino, east of Marbella, Spain.

- On 17 January, two dead bodies are found on the beach of Las Verdas, Benalmádena beach, Spain.

- On 23 January, a body is found floating next to La Caleta beach, Malaga, Spain.

- On 24 January, a body is found floating next to the beach of Nerja, Spain.

Since 17 people went missing on their crossing to Almeria between 16 and 25 January, we assume that these bodies are some of those who drowned in the various shipwrecks of that period.

On 18 January, the lifeless body of a person who was travelling in a boat with nine other men is recovered off the coast of Carboneras, Almeria, Spain.

On 24 January, there is still no trace of a boat with 43 people that had left Nouadhibou, Mauritania on 05 January. There are seven women and two children among the people who tried to take the route to the Canary Islands.

On 25 January, 19 people die and nine people survive a shipwreck 77km south-east of Lanzarote, Spain.

On 01 February, at least two people die when a rubber boat capsizes 100km off Plage David, Ben Slimane, Morocco. The number of missing people is unclear. The boat was carrying around 50 people but only seven were rescued.

On 01 February, Alarm Phone Morocco reports that a person dies during the rescue operation of a boat with 58 people off the coast of Tarfaya, Morocco.

On 02 February, at least one man dies and another is evacuated by helicopter to hospital after a boat goes down with around 50 people on board 35 km south of Morro Jable, Fuerteventura, Canary Islands, Spain.

On 05 February, Alarm Phone Morocco finds out about the shipwreck of a boat carrying 58 people which happened off the coast of Tarfaya, Morocco. Eight people did not survive the tragedy according to the research of Alarm Phone.

On 06 Feburary, Alarm Phone is alerted to a rubber boat carrying 52 people 75 nautical miles south-west of Boujdour, Western Sahara. Due to harsh weather conditions and the bad condition of the boat the people on board are in great danger. Alarm Phone informs the authorities immediately but rescue is delayed for hours. Four people are dead before the rescue vessel arrives.

On 07 February, a boat with 68 people onboard wrecks 85 km south of Gran Canaria, Canary Islands, Spain. 65 people are rescued but three people had jumped from the rubber boat and lost their lives before the rescue started.

On 13 February, the remains of a person are washed ashore at the beach of Targha, Chefchaouen, Morocco.

On 22 February, 40 people are rescued after nine days adrift off the coast of Sidi Ifni, Morocco. Three people had already died.

On 23 February, Alarm Phone is informed about a shipwreck with 87-94 people off the coast of Imtlan, Western Sahara. Three dead bodies are recovered onboard after four days at sea, 47 people are rescued, but 37-44 people remain missing.

4 Global day of struggle: CommemorActions 2022 on the occasion of 6 February

The work of Alarm Phone primarily consists of supporting people in distress via phone during their crossing. But in most cases, the work goes far beyond that. In addition to documenting illegal push-backs and failure by the authorities to provide assistance, we also sometimes end up supporting families in the search for their lost loved ones. When a boat disappears, relatives often remain without information for months, receive hardly any support from the state and feel left alone in the attempt to find their loved ones. This is often the case in the Gambia, a common starting point for boats on the Atlantic route. Unfortunately, Alarm Phone is not really active in this region but some of our activists who live in this region told us about a case in which they became involved in late January:

On 08 November 2021, a boat with Gambian and Senegalese nationals started from The Gambia to reach the Canary Islands. They were a group of about 165 people, 8 of them women. After two days their relatives lost contact to them and have not heard from them since. Alarm Phone met with several families in Gunjur, The Gambia. They are still desperatly looking for a group of 35 young people from their village who had joined the boat. Until today, they did not receive any governmental support in their attempt to find their relatives.

According to the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), only “13% of people who drowned en route to Europe in the Mediterranean and Atlantic Ocean between 2014 and 2019 were ever found or buried in Southern Europe.” Given that funerals are an important step in the process of mourning, not being able to bury lost relatives and friends or to remain in uncertainty about their fate keeps people from being able to find closure with their grief. This said, it can give all the more strength to step out of one’s supposed helplessness into action together and to publicly commemorate the missing and at the same time denounce the deadly border regime and those responsible for it.

This is why every year since the Tarajal massacre in 2014, thousands of people around the globe take to the streets on 06 February, the Global Day of Struggle, in response to the call to action to organise decentralised “commemorActions”. These are actions that commemorate those who have died, gone missing or become forcibly disappeared on their journeys across borders. This year, such commemorActions took place in Cameroon, Gambia, Tunisia, Mali, Morocco, Mauritania, Niger, Senegal, Turkey, Mexico, France, Germany, Greece, Malta, Serbia, Slovenia, Spain, Italy, UK, and elsewhere.

You can find a collection of videos and photos on social media (#CommemorActions). Meanwhile our sister organisation “Missing at the Borders” is collecting footage from all the cities where commemorActions took place. Here are some images from events Alarm Phone activists (co-)organised on 06 February, 2022:

Serrekunda, the Gambia. Source: Alarm Phone, 2022

Serrekunda, the Gambia. Source: Alarm Phone, 2022

Île de Gorée, Dakar – Senegal. Source: Alarm Phone, 2022

Île de Gorée, Dakar – Senegal. Source: Alarm Phone, 2022

Île de Gorée, Dakar – Senegal. Source: Alarm Phone, 2022

Île de Gorée, Dakar – Senegal. Source: Alarm Phone, 2022

Palermo, Italy . Source: twitter @BorderlineEurop, 2022

Palermo, Italy . Source: twitter @BorderlineEurop, 2022

Palermo, Italy. Source: twitter @BorderlineEurop, 2022

Palermo, Italy. Source: twitter @BorderlineEurop, 2022

Oujda, Morocco. Source: Facebook, AMSV Oujda, 2022

Oujda, Morocco. Source: Facebook, AMSV Oujda, 2022

Berlin, Germany. Source: twitter @NoBorder_Berlin, 2022

Berlin, Germany. Source: twitter @NoBorder_Berlin, 2022

Milano, Italy. Source: twitter @abolishfrontex, 2022

Milano, Italy. Source: twitter @abolishfrontex, 2022

In September 2022, another grand CommemorAction is going to take place in Tunisia. We hope to see you there or at one of the many protests in the daily struggle against the powerful’s inhuman politics of migration. Let’s continue to commemorate people, not numbers, and fight together for freedom of movement for all!